World J Mens Health.

2020 Jan;38(1):9-23. 10.5534/wjmh.180066.

Microtubular Dysfunction and Male Infertility

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Ondokuz Mayis University, Samsun, Turkey.

- 2Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, MAHSA University, Selangor, Malaysia.

- 3Department of Medical Bioscience, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa.

- 4Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- 5University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- 6Alfaisal University Medical School, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- 7American Center for Reproductive Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA. agarwaa@ccf.org

- KMID: 2465406

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.180066

Abstract

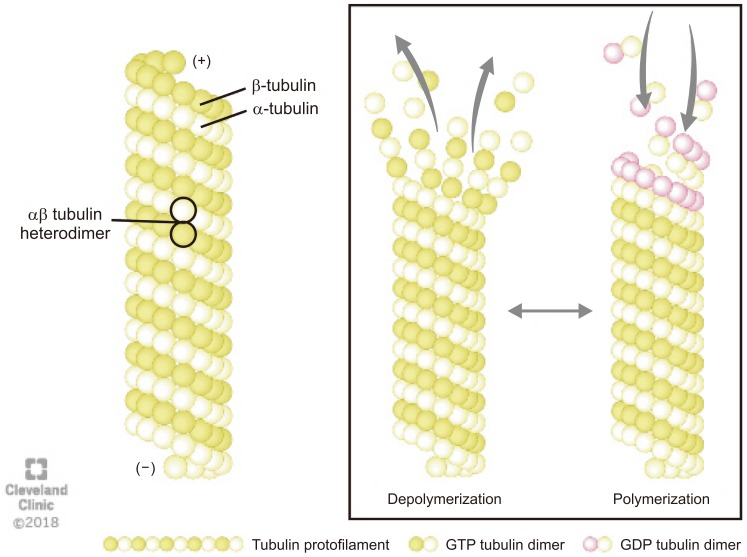

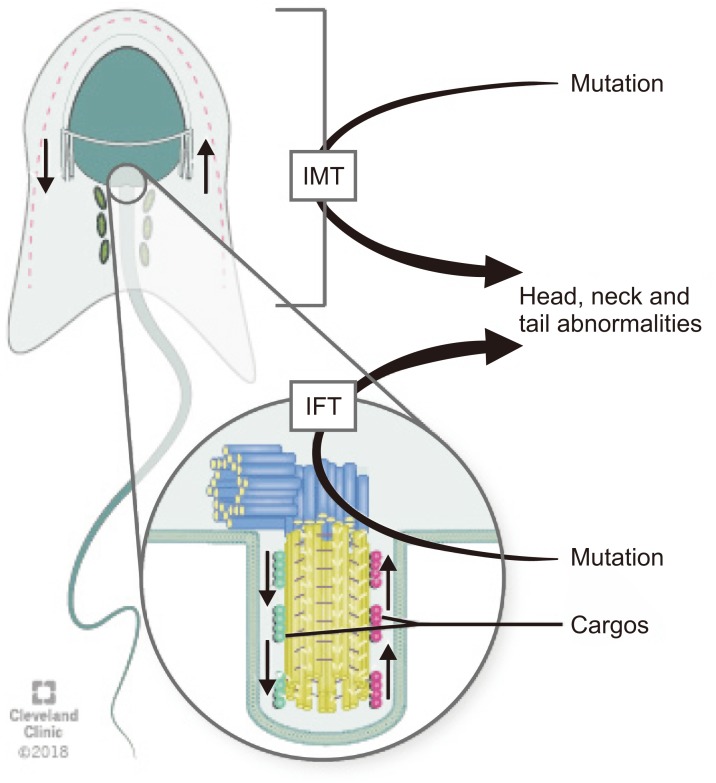

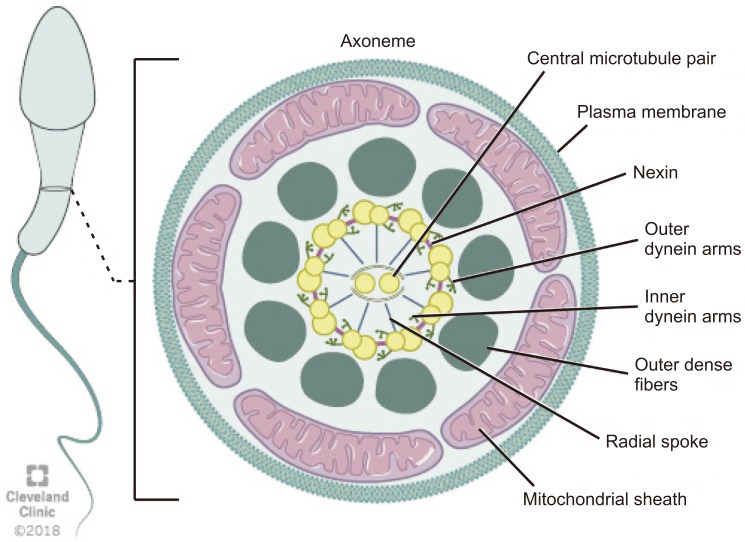

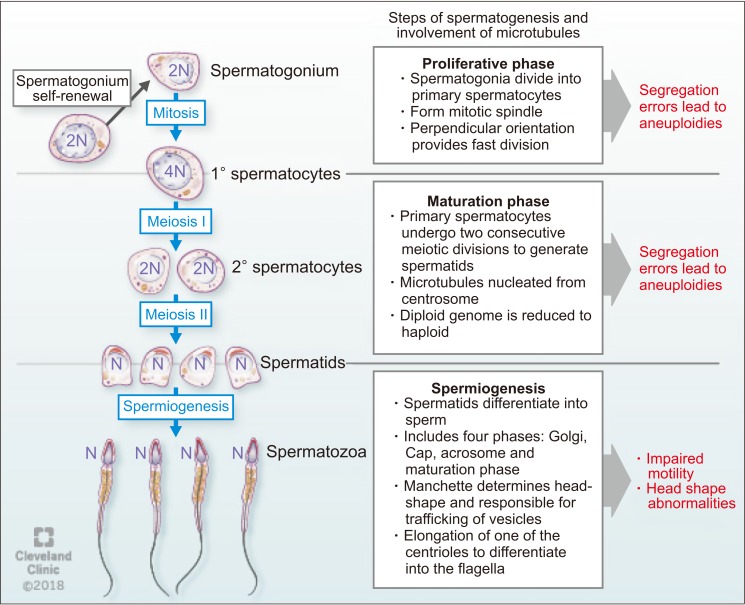

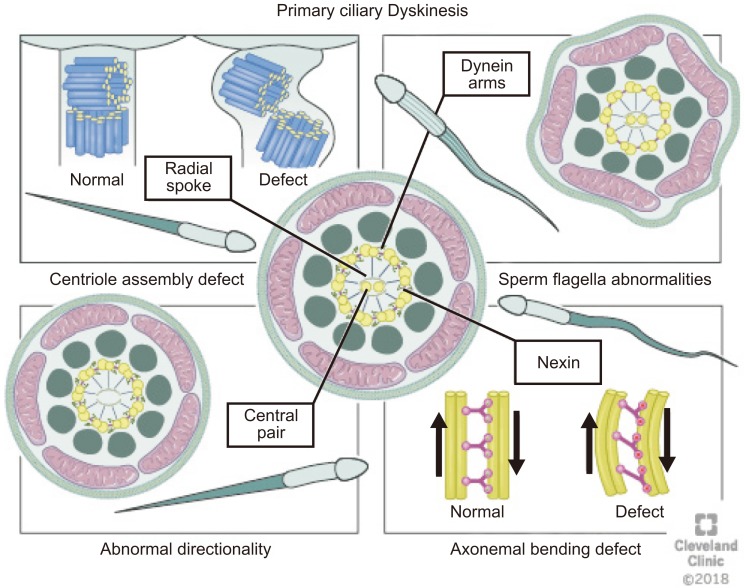

- Microtubules are the prime component of the cytoskeleton along with microfilaments. Being vital for organelle transport and cellular divisions during spermatogenesis and sperm motility process, microtubules ascertain functional capacity of sperm. Also, microtubule based structures such as axoneme and manchette are crucial for sperm head and tail formation. This review (a) presents a concise, yet detailed structural overview of the microtubules, (b) analyses the role of microtubule structures in various male reproductive functions, and (c) presents the association of microtubular dysfunctions with male infertility. Considering the immense importance of microtubule structures in the formation and maintenance of physiological functions of sperm cells, this review serves as a scientific trigger in stimulating further male infertility research in this direction.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Tuttelmann F, Gromoll J, Kliesch S. Genetics of male infertility. Urologe A. 2008; 47:1561–1562. 1564–1567. PMID: 18953522.2. Beyaz CC, Gunes S, Onem K, Kulac T, Asci R. Partial deletions of Y-chromosome in infertile men with non-obstructive azoospermia and oligoasthenoteratozoospermia in a Turkish population. In Vivo. 2017; 31:365–371. PMID: 28438864.

Article3. Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM, et al. World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update. 2010; 16:231–245. PMID: 19934213.

Article4. Kaverina I, Straube A. Regulation of cell migration by dynamic microtubules. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011; 22:968–974. PMID: 22001384.

Article5. Watanabe T, Noritake J, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of microtubules in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2005; 15:76–83. PMID: 15695094.

Article6. Glotzer M. The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009; 10:9–20. PMID: 19197328.

Article7. Linck RW, Chemes H, Albertini DF. The axoneme: the propulsive engine of spermatozoa and cilia and associated ciliopathies leading to infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016; 33:141–156. PMID: 26825807.

Article8. Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015; 16:711–726. PMID: 26562752.

Article9. O'Donnell L, O'Bryan MK. Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014; 30:45–54. PMID: 24440897.10. Halpain S, Dehmelt L. The MAP1 family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2006; 7:224. PMID: 16938900.

Article11. Mohri H, Inaba K, Ishijima S, Baba SA. Tubulin-dynein system in flagellar and ciliary movement. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2012; 88:397–415.

Article12. Fujita H, Yoshino Y, Chiba N. Regulation of the centrosome cycle. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015; 3:e1075643. PMID: 27308597.

Article14. Linck RW, Chemes H, Albertini DF. The axoneme: the propulsive engine of spermatozoa and cilia and associated ciliopathies leading to infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016; 33:141–156. PMID: 26825807.

Article15. Liu Y, DeBoer K, de Kretser DM, O'Donnell L, O'Connor AE, Merriner DJ, et al. LRGUK-1 is required for basal body and manchette function during spermatogenesis and male fertility. PLoS Genet. 2015; 11:e1005090. PMID: 25781171.

Article16. Sun X, Kovacs T, Hu YJ, Yang WX. The role of actin and myosin during spermatogenesis. Mol Biol Rep. 2011; 38:3993–4001. PMID: 21107714.

Article17. Kierszenbaum AL. Intramanchette transport (IMT): managing the making of the spermatid head, centrosome, and tail. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002; 63:1–4. PMID: 12211054.

Article18. Lehti MS, Sironen A. Formation and function of the manchette and flagellum during spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2016; 151:R43–R54. PMID: 26792866.

Article19. Gob E, Schmitt J, Benavente R, Alsheimer M. Mammalian sperm head formation involves different polarization of two novel LINC complexes. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e12072. PMID: 20711465.

Article20. Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hale CM, Wirtz D, Hodzic D. Structural requirements for the assembly of LINC complexes and their function in cellular mechanical stiffness. Exp Cell Res. 2008; 314:1892–1905. PMID: 18396275.

Article21. Pasch E, Link J, Beck C, Scheuerle S, Alsheimer M. The LINC complex component Sun4 plays a crucial role in sperm head formation and fertility. Biol Open. 2015; 4:1792–1802. PMID: 26621829.

Article22. Calvi A, Wong AS, Wright G, Wong ES, Loo TH, Stewart CL, et al. SUN4 is essential for nuclear remodeling during mammalian spermiogenesis. Dev Biol. 2015; 407:321–330. PMID: 26417726.

Article23. Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012; 149:1035–1047. PMID: 22632968.

Article24. Wren KN, Craft JM, Tritschler D, Schauer A, Patel DK, Smith EF, et al. A differential cargo-loading model of ciliary length regulation by IFT. Curr Biol. 2013; 23:2463–2471. PMID: 24316207.

Article25. Craft JM, Harris JA, Hyman S, Kner P, Lechtreck KF. Tubulin transport by IFT is upregulated during ciliary growth by a cilium-autonomous mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2015; 208:223–237. PMID: 25583998.

Article26. Hayasaka S, Terada Y, Suzuki K, Murakawa H, Tachibana I, Sankai T, et al. Intramanchette transport during primate spermiogenesis: expression of dynein, myosin Va, motor recruiter myosin Va, VIIa-Rab27a/b interacting protein, and Rab27b in the manchette during human and monkey spermiogenesis. Asian J Androl. 2008; 10:561–568. PMID: 18478159.

Article27. Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL, Yoder BK, Haycraft CJ, Bornens M, et al. GMAP210 and IFT88 are present in the spermatid golgi apparatus and participate in the development of the acrosome-acroplaxome complex, head-tail coupling apparatus and tail. Dev Dyn. 2011; 240:723–736. PMID: 21337470.

Article28. Hamilton JA, Cissen M, Brandes M, Smeenk JM, de Bruin JP, Kremer JA, et al. Total motile sperm count: a better indicator for the severity of male factor infertility than the WHO sperm classification system. Hum Reprod. 2015; 30:1110–1121. PMID: 25788568.

Article29. Zariwala MA, Leigh MW, Ceppa F, Kennedy MP, Noone PG, Carson JL, et al. Mutations of DNAI1 in primary ciliary dyskinesia: evidence of founder effect in a common mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 174:858–866. PMID: 16858015.30. Sha YW, Ding L, Li P. Management of primary ciliary dyskinesia/Kartagener's syndrome in infertile male patients and current progress in defining the underlying genetic mechanism. Asian J Androl. 2014; 16:101–106. PMID: 24369140.

Article31. Subramanian R, Kapoor TM. Building complexity: insights into self-organized assembly of microtubule-based architectures. Dev Cell. 2012; 23:874–885. PMID: 23153484.

Article32. Vale RD. The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell. 2003; 112:467–480. PMID: 12600311.

Article33. Akhmanova A, Hoogenraad CC. Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins: mechanisms and functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005; 17:47–54. PMID: 15661518.

Article34. Peterman EJ, Scholey JM. Mitotic microtubule crosslinkers: insights from mechanistic studies. Curr Biol. 2009; 19:R1089–R1094. PMID: 20064413.

Article35. Kollman JM, Merdes A, Mourey L, Agard DA. Microtubule nucleation by gamma-tubulin complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011; 12:709–721. PMID: 21993292.36. Howard J, Hyman AA. Growth, fluctuation and switching at microtubule plus ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009; 10:569–574. PMID: 19513082.

Article37. Bertalan Z, Budrikis Z, La Porta CA, Zapperi S. Role of the number of microtubules in chromosome segregation during cell division. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0141305. PMID: 26506005.

Article38. Helmke KJ, Heald R, Wilbur JD. Interplay between spindle architecture and function. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013; 306:83–125. PMID: 24016524.

Article39. Navolanic PM, Sperry AO. Identification of isoforms of a mitotic motor in mammalian spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2000; 62:1360–1369. PMID: 10775188.40. Tang EI, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Regulation of microtubule (MT)-based cytoskeleton in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016; 59:35–45. PMID: 26791048.

Article41. Lagos-Cabre R, Moreno RD. Mitotic, but not meiotic, oriented cell divisions in rat spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2008; 135:471–478. PMID: 18296512.

Article42. Holstein AF. Ultrastructural observations on the differentiation of spermatids in man. Andrologia. 1976; 8:157–165. PMID: 962174.

Article43. Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. The acrosome-acroplaxomemanchette complex and the shaping of the spermatid head. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004; 67:271–284. PMID: 15700535.

Article44. Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL. Cytoskeletal track selection during cargo transport in spermatids is relevant to male fertility. Spermatogenesis. 2011; 1:221–230. PMID: 22319670.

Article45. Eddy EM. The spermatozoon. In : Knobil E, Neill J, editors. Knobil and Neill's physiology of reproduction. St Louis: Acedemc Press;2006. p. 3–54.46. Zini A, Agarwal A. Spermatogenesis. In : Zini A, Agarwal A, editors. Sperm Chromatin. New York: Springer;2012. p. 19–39.47. Kramer H, Phistry M. Genetic analysis of hook, a gene required for endocytic trafficking in drosophila. Genetics. 1999; 151:675–684. PMID: 9927460.48. Baron Gaillard CL, Pallesi-Pocachard E, Massey-Harroche D, Richard F, Arsanto JP, Chauvin JP, et al. Hook2 is involved in the morphogenesis of the primary cilium. Mol Biol Cell. 2011; 22:4549–4562. PMID: 21998199.

Article49. Schwarz T, Prieler B, Schmid JA, Grzmil P, Neesen J. Ccdc181 is a microtubule-binding protein that interacts with Hook1 in haploid male germ cells and localizes to the sperm tail and motile cilia. Eur J Cell Biol. 2017; 96:276–288. PMID: 28283191.

Article50. Mendoza-Lujambio I, Burfeind P, Dixkens C, Meinhardt A, Hoyer-Fender S, Engel W, et al. The Hook1 gene is nonfunctional in the abnormal spermatozoon head shape (azh) mutant mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2002; 11:1647–1658. PMID: 12075009.

Article51. Kim YH, Haidl G, Schaefer M, Egner U, Mandal A, Herr JC. Compartmentalization of a unique ADP/ATP carrier protein SFEC (Sperm Flagellar Energy Carrier, AAC4) with glycolytic enzymes in the fibrous sheath of the human sperm flagellar principal piece. Dev Biol. 2007; 302:463–476. PMID: 17137571.

Article52. TAlberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Sperm. In : Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P, editors. Molecular biology of the cell. New York: Garland Science;2002.53. Hartman JJ, Mahr J, McNally K, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Thomas S, et al. Katanin, a microtubule-severing protein, is a novel AAA ATPase that targets to the centrosome using a WD40-containing subunit. Cell. 1998; 93:277–287. PMID: 9568719.

Article54. O'Donnell L, Rhodes D, Smith SJ, Merriner DJ, Clark BJ, Borg C, et al. An essential role for katanin p80 and microtubule severing in male gamete production. PLoS Genet. 2012; 8:e1002698. PMID: 22654669.55. Pleuger C, Fietz D, Hartmann K, Weidner W, Kliesch S, O'Bryan MK, et al. Expression of katanin p80 in human spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril. 2016; 106:1683–1690.e1. PMID: 27717557.

Article56. Venkatesh D, Mruk D, Herter JM, Cullere X, Chojnacka K, Cheng CY, et al. AKAP9, a regulator of microtubule dynamics, contributes to blood-testis barrier function. Am J Pathol. 2016; 186:270–284. PMID: 26687990.

Article57. Vogl AW, Weis M, Pfeiffer DC. The perinuclear centriolecontaining centrosome is not the major microtubule organizing center in Sertoli cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995; 66:165–179. PMID: 7774603.58. Cheung K, Senese S, Kuang J, Bui N, Ongpipattanakul C, Gholkar A, et al. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian Katanin family of microtubule-severing enzymes defines Katanin p80 subunit B-like 1 (KATNBL1) as a regulator of mammalian katanin microtubule-severing. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016; 15:1658–1669. PMID: 26929214.

Article59. Smith LB, Milne L, Nelson N, Eddie S, Brown P, Atanassova N, et al. KATNAL1 regulation of sertoli cell microtubule dynamics is essential for spermiogenesis and male fertility. PLoS Genet. 2012; 8:e1002697. PMID: 22654668.

Article60. De Gendt K, Denolet E, Willems A, Daniels VW, Clinckemalie L, Denayer S, et al. Expression of Tubb3, a beta-tubulin isotype, is regulated by androgens in mouse and rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2011; 85:934–945. PMID: 21734264.61. Fedick AM, Eckert K, Thompson K, Forman EJ, Devkota B, Treff NR, et al. Lack of association of KATNAL1 gene sequence variants and azoospermia in humans. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014; 31:1065–1071. PMID: 24913027.

Article62. Lobo LJ, Zariwala MA, Noone PG. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. QJM. 2014; 107:691–699. PMID: 24652656.

Article63. Kartagener M, Horlacher A. Situs viscerum inversus und Polyposis nasi in einem Falle familiaerer Bronchiektasien. Beitr Klin Tuberk. 1935; 87:331–333.64. Afzelius BA. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science. 1976; 193:317–319. PMID: 1084576.

Article65. Barbato A, Frischer T, Kuehni CE, Snijders D, Azevedo I, Baktai G, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: a consensus statement on diagnostic and treatment approaches in children. Eur Respir J. 2009; 34:1264–1276. PMID: 19948909.

Article66. Kuehni CE, Frischer T, Strippoli MP, Maurer E, Bush A, Nielsen KG, et al. Factors influencing age at diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia in European children. Eur Respir J. 2010; 36:1248–1258. PMID: 20530032.

Article67. Afzelius BA, Eliasson R, Johnsen O, Lindholmer C. Lack of dynein arms in immotile human spermatozoa. J Cell Biol. 1975; 66:225–232. PMID: 1141381.

Article68. Pedersen H, Rebbe H. Absence of arms in the axoneme of immobile human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 1975; 12:541–544. PMID: 1220825.

Article69. Ji ZY, Sha YW, Ding L, Li P. Genetic factors contributing to human primary ciliary dyskinesia and male infertility. Asian J Androl. 2017; 19:515–520. PMID: 27270341.

Article70. Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. The self-assembly and dynamic structure of cytoskeletal filaments. In : Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P, editors. Molecular biology of the cell. New York: Garland Science;2002.71. Kurkowiak M, Ziętkiewicz E, Witt M. Recent advances in primary ciliary dyskinesia genetics. J Med Genet. 2015; 52:1–9. PMID: 25351953.

Article72. Stannard W, Rutman A, Wallis C, O'Callaghan C. Central microtubular agenesis causing primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 169:634–637. PMID: 14982824.

Article73. Chodhari R, Mitchison HM, Meeks M. Cilia, primary ciliary dyskinesia and molecular genetics. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004; 5:69–76. PMID: 15222957.

Article74. Wambergue C, Zouari R, Fourati Ben, Martinez G, Devillard F, Hennebicq S, et al. Patients with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flag ella due to DNAH1 mutations have a good prognosis following intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 2016; 31:1164–1172. PMID: 27094479.75. Buchdahl RM, Reiser J, Ingram D, Rutman A, Cole PJ, Warner JO. Ciliary abnormalities in respiratory disease. Arch Dis Child. 1988; 63:238–243. PMID: 3355203.

Article76. Wilton LJ, Teichtahl H, Temple-Smith PD, de Kretser DM. Structural heterogeneity of the axonemes of respiratory cilia and sperm flagella in normal men. J Clin Invest. 1985; 75:825–831. PMID: 3156880.

Article77. Lee L. Mechanisms of mammalian ciliary motility: insights from primary ciliary dyskinesia genetics. Gene. 2011; 473:57–66. PMID: 21111794.

Article78. Ishiguro T, Takayanagi N, Hijikata N, Yoshii Y, Yoneda K, Miyahara Y, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. A case report and comparison with 4 previous cases. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2009; 47:242–248. PMID: 19348274.79. Bartoloni L, Blouin JL, Pan Y, Gehrig C, Maiti AK, Scamuffa N, et al. Mutations in the DNAH11 (axonemal heavy chain dynein type 11) gene cause one form of situs inversus totalis and most likely primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99:10282–10286. PMID: 12142464.

Article80. Omran H, Haffner K, Volkel A, Kuehr J, Ketelsen UP, Ross UH, et al. Homozygosity mapping of a gene locus for primary ciliary dyskinesia on chromosome 5p and identification of the heavy dynein chain DNAH5 as a candidate gene. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000; 23:696–702. PMID: 11062149.81. Pennarun G, Chapelin C, Escudier E, Bridoux AM, Dastot F, Cacheux V, et al. The human dynein intermediate chain 2 gene (DNAI2): cloning, mapping, expression pattern, and evaluation as a candidate for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Hum Genet. 2000; 107:642–649. PMID: 11153919.

Article82. Mazor M, Alkrinawi S, Chalifa-Caspi V, Manor E, Sheffield VC, Aviram M, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia caused by homozygous mutation in DNAL1, encoding dynein light chain 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2011; 88:599–607. PMID: 21496787.

Article83. Mitchison HM, Schmidts M, Loges NT, Freshour J, Dritsoula A, Hirst RA, et al. Mutations in axonemal dynein assembly factor DNAAF3 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia. Nat Genet. 2012; 44:381–389. s1–s2. PMID: 22387996.

Article84. Castleman VH, Romio L, Chodhari R, Hirst RA, de Castro SC, Parker KA, et al. Mutations in radial spoke head protein genes RSPH9 and RSPH4A cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with central-microtubular-pair abnormalities. Am J Hum Genet. 2009; 84:197–209. PMID: 19200523.

Article85. El Khouri E, Thomas L, Jeanson L, Bequignon E, Vallette B, Duquesnoy P, et al. Mutations in DNAJB13, encoding an HSP40 family member, cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and male infertility. Am J Hum Genet. 2016; 99:489–500. PMID: 27486783.86. Chemes HE, Olmedo SB, Carrere C, Oses R, Carizza C, Leisner M, et al. Ultrastructural pathology of the sperm flagellum: association between flagellar pathology and fertility prognosis in severely asthenozoospermic men. Hum Reprod. 1998; 13:2521–2526. PMID: 9806277.

Article87. Baccetti B, Capitani S, Collodel G, Di Cairano G, Gambera L, Moretti E, et al. Genetic sperm defects and consanguinity. Hum Reprod. 2001; 16:1365–1371. PMID: 11425814.

Article88. Baccetti B, Collodel G, Estenoz M, Manca D, Moretti E, Piomboni P. Gene deletions in an infertile man with sperm fibrous sheath dysplasia. Hum Reprod. 2005; 20:2790–2794. PMID: 15980003.

Article89. Brown PR, Miki K, Harper DB, Eddy EM. A-kinase anchoring protein 4 binding proteins in the fibrous sheath of the sperm flagellum. Biol Reprod. 2003; 68:2241–2248. PMID: 12606363.

Article90. Turner RM, Johnson LR, Haig-Ladewig L, Gerton GL, Moss SB. An X-linked gene encodes a major human sperm fibrous sheath protein, hAKAP82. Genomic organization, protein kinase A-RII binding, and distribution of the precursor in the sperm tail. J Biol Chem. 1998; 273:32135–32141. PMID: 9822690.91. Chemes HE, Rawe VY. The making of abnormal spermatozoa: cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying pathological spermiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2010; 341:349–357. PMID: 20596874.

Article92. Rawe VY, Olmedo SB, Benmusa A, Shiigi SM, Chemes HE, Sutovsky P. Sperm ubiquitination in patients with dysplasia of the fibrous sheath. Hum Reprod. 2002; 17:2119–2127. PMID: 12151447.

Article93. Rives NM. Chromosome abnormalities in sperm from infertile men with normal somatic karyotypes: asthenozoospermia. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005; 111:358–362. PMID: 16192716.

Article94. Coutton C, Escoffier J, Martinez G, Arnoult C, Ray PF. Teratozoospermia: spotlight on the main genetic actors in the human. Hum Reprod Update. 2015; 21:455–485. PMID: 25888788.

Article95. Viville S, Mollard R, Bach ML, Falquet C, Gerlinger P, Warter S. Do morphological anomalies reflect chromosomal aneuploidies?: case report. Hum Reprod. 2000; 15:2563–2566. PMID: 11098027.

Article96. Teves ME, Sears PR, Li W, Zhang Z, Tang W, van Reesema L, et al. Sperm-associated antigen 6 (SPAG6) deficiency and defects in ciliogenesis and cilia function: polarity, density, and beat. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e107271. PMID: 25333478.

Article97. Tokuhiro K, Isotani A, Yokota S, Yano Y, Oshio S, Hirose M, et al. OAZ-t/OAZ3 is essential for rigid connection of sperm tails to heads in mouse. PLoS Genet. 2009; 5:e1000712. PMID: 19893612.

Article98. Zhu F, Wang F, Yang X, Zhang J, Wu H, Zhang Z, et al. Biallelic SUN5 mutations cause autosomal-recessive acephalic spermatozoa syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2016; 99:1405.

Article99. Liska F, Gosele C, Rivkin E, Tres L, Cardoso MC, Domaing P, et al. Rat hd mutation reveals an essential role of centrobin in spermatid head shaping and assembly of the head-tail coupling apparatus. Biol Reprod. 2009; 81:1196–1205. PMID: 19710508.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A case of prolactinoma with chief complaint of male infertility

- Genetic Causes in Male Infertility and Current Studies on Infertility Genes

- Sexual Dysfunction and Fertility Problems in Men with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Anejaculation in Patients with Adequate Erection and Intercourse

- Causes and Diagnosis of Female Infertility