Intest Res.

2018 Jul;16(3):358-365. 10.5217/ir.2018.16.3.358.

Serrated neoplasia pathway as an alternative route of colorectal cancer carcinogenesis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine and Institute of Gastroenterology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. taeilkim@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2417647

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2018.16.3.358

Abstract

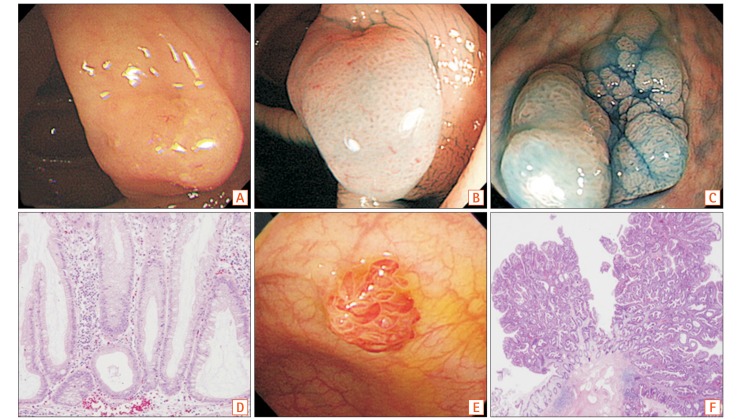

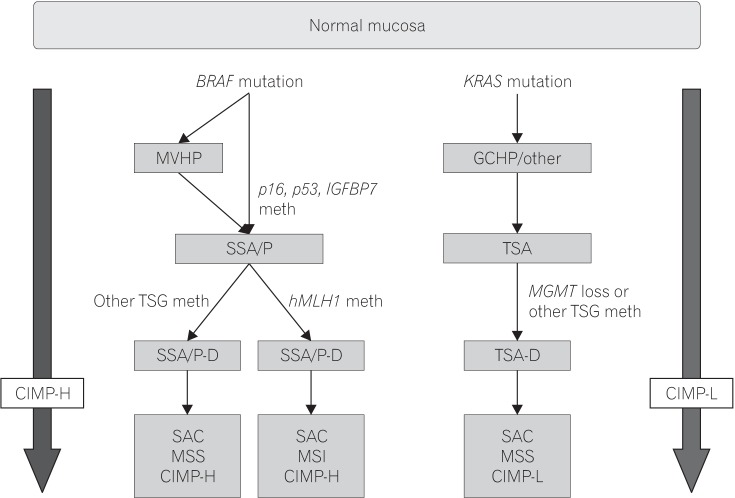

- In the past two decades, besides conventional adenoma pathway, a subset of colonic lesions, including hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps, and traditional serrated adenomas have been suggested as precancerous lesions via the alternative serrated neoplasia pathway. Major molecular alterations of sessile serrated neoplasia include BRAF mutation, high CpG island methylator phenotype, and escape of cellular senescence and progression via methylation of tumor suppressor genes or mismatch repair genes. With increasing information of the morphologic and molecular features of serrated lesions, one major challenge is how to reflect this knowledge in clinical practice, such as pathologic and endoscopic diagnosis, and guidelines for treatment and surveillance.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Postgastrectomy gastric cancer patients are at high risk for colorectal neoplasia: a case control study

Tae-Geun Gweon, Kyu-Tae Yoon, Chang Hyun Kim, Jin-Jo Kim

Intest Res. 2021;19(2):239-246. doi: 10.5217/ir.2020.00009.Summary and comparison of recently updated post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines

Yoon Suk Jung

Intest Res. 2023;21(4):443-451. doi: 10.5217/ir.2023.00107.

Reference

-

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017; 67:7–30. PMID: 28055103.

Article2. Tsoi KKF, Hirai HW, Chan FC, Griffiths S, Sung JJ. predicted increases in incidence of colorectal cancer in developed and developing regions, in association with ageing populations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 15:892–900. PMID: 27720911.3. Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975; 36:2251–2270. PMID: 1203876.

Article4. Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011; 42:1–10. PMID: 20869746.

Article5. Boparai KS, Dekker E, Polak MM, Musler AR, van Eeden S, van Noesel CJ. A serrated colorectal cancer pathway predominates over the classic WNT pathway in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2011; 178:2700–2707. PMID: 21641392.

Article6. East JE, Saunders BP, Jass JR. Sporadic and syndromic hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colon: classification, molecular genetics, natural history, and clinical management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008; 37:25–46. PMID: 18313538.

Article7. Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013; 62:367–386. PMID: 23339363.

Article8. Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H, et al. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2009; 54:906–909. PMID: 18688718.

Article9. Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010; 63:681–686. PMID: 20547691.

Article10. Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007; 50:113–130. PMID: 17204026.

Article11. Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; 96:8681–8686. PMID: 10411935.

Article12. Snover D. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In : Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC;2010. p. 160–165.13. Burgess NG, Tutticci NJ, Pellise M, Bourke MJ. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with cytologic dysplasia: a triple threat for interval cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 80:307–310. PMID: 24890425.

Article14. Arain MA, Sawhney M, Sheikh S, et al. CIMP status of interval colon cancers: another piece to the puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:1189–1195. PMID: 20010923.

Article15. le Clercq CM, Sanduleanu S. Interval colorectal cancers: what and why. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014; 16:375. PMID: 24532192.

Article16. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1095–1105. PMID: 24047059.

Article17. Arthur JF. Structure and significance of metaplastic nodules in the rectal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1968; 21:735–743. PMID: 5717544.

Article18. Hazewinkel Y, de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, et al. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014; 46:219–224. PMID: 24254386.

Article19. Carr NJ, Mahajan H, Tan KL, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009; 62:516–518. PMID: 19126563.

Article20. Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1315–1329. PMID: 22710576.

Article21. Aust DE, Baretton GB. Members of the Working Group GI-Pathology of the German Society of Pathology. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)-proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 2010; 457:291–297. PMID: 20617338.

Article22. Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, Torlakovic G, Nesland JM. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:65–81. PMID: 12502929.

Article23. O'Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C, et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 30:1491–1501. PMID: 17122504.24. Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Phipps AI, et al. Colorectal endoscopy, advanced adenomas, and sessile serrated polyps: implications for proximal colon cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1213–1219. PMID: 22688851.

Article25. Fernando WC, Miranda MS, Worthley DL, et al. The CIMP phenotype in BRAF mutant serrated polyps from a prospective colonoscopy patient cohort. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014; 2014:374926. PMID: 24812557.26. Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2088–2100. PMID: 20420948.

Article27. Rosty C, Hewett DG, Brown IS, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Gastroenterol. 2013; 48:287–302. PMID: 23208018.

Article28. Rosenberg DW, Yang S, Pleau DC, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS differentially distinguish serrated versus non-serrated hyperplastic aberrant crypt foci in humans. Cancer Res. 2007; 67:3551–3554. PMID: 17440063.29. Spring KJ, Zhao ZZ, Karamatic R, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131:1400–1407. PMID: 17101316.30. Huang CS, Farraye FA, Yang S, O'Brien MJ. The clinical significance of serrated polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:229–240. PMID: 21045813.31. Arnold CA, Montgomery E, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. The serrated pathway of neoplasia: new insights into an evolving concept. Diagn Histopathol. 2011; 17:367–375.32. Torlakovic E, Snover DC. Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996; 110:748–755. PMID: 8608884.33. Vieth M, Quirke P, Lambert R, von Karsa L, Risio M. Annex to Quirke et al. Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: annotations of colorectal lesions. Virchows Arch. 2011; 458:21–30. PMID: 21061132.34. East JE, Atkin WS, Bateman AC, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology position statement on serrated polyps in the colon and rectum. Gut. 2017; 66:1181–1196. PMID: 28450390.

Article35. Kahi CJ, Li X, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. High colonoscopic prevalence of proximal colon serrated polyps in average-risk men and women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 75:515–520. PMID: 22018551.

Article36. Hetzel JT, Huang CS, Coukos JA, et al. Variation in the detection of serrated polyps in an average risk colorectal cancer screening cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:2656–2664. PMID: 20717107.

Article37. Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Kahi CJ, Cummings OW, Snover DC, Rex DK. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:517–524. PMID: 24998465.

Article38. Bouwens MW, van Herwaarden YJ, Winkens B, et al. Endoscopic characterization of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with and without dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2014; 46:225–235. PMID: 24573732.

Article39. Chung SM, Chen YT, Panczykowski A, Schamberg N, Klimstra DS, Yantiss RK. Serrated polyps with “intermediate features” of sessile serrated polyp and microvesicular hyperplastic polyp: a practical approach to the classification of nondysplastic serrated polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:407–412. PMID: 18300810.

Article40. Wiland HO 4th, Shadrach B, Allende D, et al. Morphologic and molecular characterization of traditional serrated adenomas of the distal colon and rectum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014; 38:1290–1297. PMID: 25127095.

Article41. Jaramillo E, Tamura S, Mitomi H. Endoscopic appearance of serrated adenomas in the colon. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:254–260. PMID: 15731942.

Article42. Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:21–29. PMID: 18162766.

Article43. Yantiss RK, Oh KY, Chen YT, Redston M, Odze RD. Filiform serrated adenomas: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:1238–1245. PMID: 17667549.44. Ha SY, Lee SM, Lee EJ, et al. Filiform serrated adenoma is an unusual, less aggressive variant of traditional serrated adenoma. Pathology. 2012; 44:18–23. PMID: 22157687.

Article45. Pino MS, Chung DC. The chromosomal instability pathway in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2059–2072. PMID: 20420946.

Article46. Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, et al. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129:837–845. PMID: 16143123.

Article47. Hawkins N, Norrie M, Cheong K, et al. CpG island methylation in sporadic colorectal cancers and its relationship to microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2002; 122:1376–1387. PMID: 11984524.

Article48. Yang S, Farraye FA, Mack C, Posnik O, O'Brien MJ. BRAF and KRAS Mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:1452–1459. PMID: 15489648.

Article49. Chan AO, Issa JP, Morris JS, Hamilton SR, Rashid A. Concordant CpG island methylation in hyperplastic polyposis. Am J Pathol. 2002; 160:529–536. PMID: 11839573.

Article50. Wynter CV, Walsh MD, Higuchi T, Leggett BA, Young J, Jass JR. Methylation patterns define two types of hyperplastic polyp associated with colorectal cancer. Gut. 2004; 53:573–580. PMID: 15016754.

Article51. Minoo P, Baker K, Goswami R, et al. Extensive DNA methylation in normal colorectal mucosa in hyperplastic polyposis. Gut. 2006; 55:1467–1474. PMID: 16469793.

Article52. Shima K, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M, et al. TGFBR2 and BAX mononucleotide tract mutations, microsatellite instability, and prognosis in 1072 colorectal cancers. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e25062. PMID: 21949851.

Article53. Edelstein DL, Axilbund JE, Hylind LM, et al. Serrated polyposis: rapid and relentless development of colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2013; 62:404–408. PMID: 22490521.

Article54. Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut. 2017; 66:97–106. PMID: 26475632.55. Burnett-Hartman AN, Passarelli MN, Adams SV, et al. Differences in epidemiologic risk factors for colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps by lesion severity and anatomical site. Am J Epidemiol. 2013; 177:625–637. PMID: 23459948.56. Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL, et al. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut. 2004; 53:1137–1144. PMID: 15247181.57. Campisi J. Suppressing cancer: the importance of being senescent. Science. 2005; 309:886–887. PMID: 16081723.58. Collado M, Serrano M. The power and the promise of oncogene-induced senescence markers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006; 6:472–476. PMID: 16723993.59. Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997; 88:593–602. PMID: 9054499.60. Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005; 436:725–730. PMID: 16079851.

Article61. Suzuki H, Igarashi S, Nojima M, et al. IGFBP7 is a p53-responsive gene specifically silenced in colorectal cancer with CpG island methylator phenotype. Carcinogenesis. 2010; 31:342–349. PMID: 19638426.

Article62. Wu JM, Montgomery EA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Frequent beta-catenin nuclear labeling in sessile serrated polyps of the colorectum with neoplastic potential. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008; 129:416–423. PMID: 18285264.

Article63. Whitehall VL, Walsh MD, Young J, Leggett BA, Jass JR. Methylation of O-6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase characterizes a subset of colorectal cancer with low-level DNA microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 2001; 61:827–830. PMID: 11221863.64. Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Ogawa A, Kirkner GJ, Loda M, Fuchs CS. TGFBR2 mutation is correlated with CpG island methylator phenotype in microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2007; 38:614–620. PMID: 17270239.

Article65. Teriaky A, Driman DK, Chande N. Outcomes of a 5-year follow-up of patients with sessile serrated adenomas. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012; 47:178–183. PMID: 22229626.

Article66. Kashida H, Ikehara N, Hamatani S, Kudo SE, Kudo M. Endoscopic characteristics of colorectal serrated lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011; 58:1163–1167. PMID: 21937375.

Article67. Williams AR, Balasooriya BA, Day DW. Polyps and cancer of the large bowel: a necropsy study in Liverpool. Gut. 1982; 23:835–842. PMID: 7117903.

Article68. Su MY, Hsu CM, Ho YP, Chen PC, Lin CJ, Chiu CT. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and narrow-band imaging systems in differential diagnosis of neoplastic and nonneoplastic colonic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:2711–2716. PMID: 17227517.

Article69. Oka S, Tanaka S, Hiyama T, et al. Clinicopathologic and endoscopic features of colorectal serrated adenoma: differences between polypoid and superficial types. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004; 59:213–219. PMID: 14745394.

Article70. Tadepalli US, Feihel D, Miller KM, et al. A morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:1360–1368. PMID: 22018553.

Article71. Rustagi T, Rangasamy P, Myers M, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas in the proximal colon are likely to be flat, large and occur in smokers. World J Gastroenterol. 2013; 19:5271–5277. PMID: 23983429.

Article72. Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, et al. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 77:916–924. PMID: 23433877.

Article73. Buda A, De Bona M, Dotti I, et al. Prevalence of different subtypes of serrated polyps and risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk population undergoing first-time colonoscopy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012; 3:e6. PMID: 23238028.

Article74. Kim MJ, Lee EJ, Suh JP, et al. Traditional serrated adenoma of the colorectum: clinicopathologic implications and endoscopic findings of the precursor lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013; 140:898–911. PMID: 24225759.75. Higuchi T, Sugihara K, Jass JR. Demographic and pathological characteristics of serrated polyps of colorectum. Histopathology. 2005; 47:32–40. PMID: 15982321.

Article76. IJspeert JE, Bastiaansen BA, van Leerdam ME, et al. Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016; 65:963–970. PMID: 25753029.

Article77. Leonard DF, Dozois EJ, Smyrk TC, et al. Endoscopic and surgical management of serrated colonic polyps. Br J Surg. 2011; 98:1685–1694. PMID: 22034178.

Article78. Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012; 143:844–857. PMID: 22763141.

Article79. Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013; 45:842–851. PMID: 24030244.

Article80. Yang DH, Hong SN, Kim YH, et al. Korean guidelines for post-polypectomy colonoscopic surveillance. Intest Res. 2012; 10:89–109.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Molecular Features of the Serrated Pathway to Colorectal Cancer: Current Knowledge and Future Directions

- Early Adenocarcinoma Arising from Traditional Serrated Adenoma in the Colon

- CpG Island Methylator Phenotype-High Colorectal Cancers and Their Prognostic Implications and Relationships with the Serrated Neoplasia Pathway

- A Case of Serrated Adenoma Presenting as Colon Cancer

- Clinical Features of Colorectal Serrated Adenomas