J Korean Med Sci.

2015 Feb;30(2):145-150. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.2.145.

Phenotypic and Functional Analysis of HL-60 Cells Used in Opsonophagocytic-Killing Assay for Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. sujin-cho@ewha.ac.kr

- 2Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2129643

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.2.145

Abstract

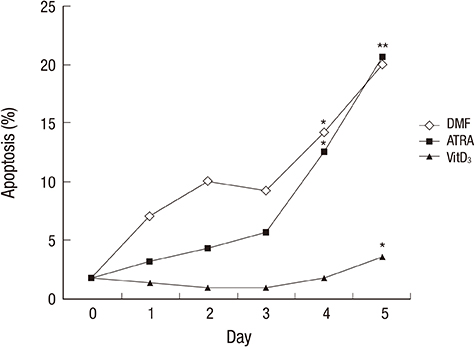

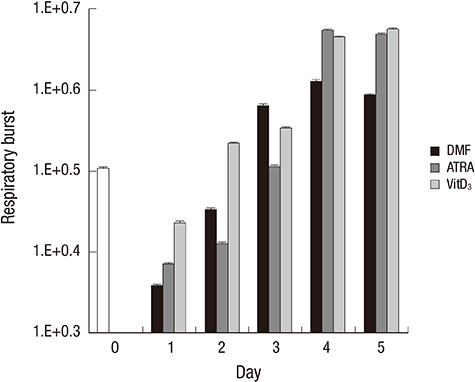

- Differentiated HL-60 is an effector cell widely used for the opsonophagocytic-killing assay (OPKA) to measure efficacy of pneumococcal vaccines. We investigated the correlation between phenotypic expression of immunoreceptors and phagocytic ability of HL-60 cells differentiated with N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) for 5 days. Phenotypic change was examined by flow cytometry with specific antibodies to CD11c, CD14, CD18, CD32, and CD64. Apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry using 7-aminoactinomycin D. Function was evaluated by a standard OPKA against serotype 19F and chemiluminescence-based respiratory burst assay. The expression of CD11c and CD14 gradually increased upon exposure to all three agents, while CD14 expression increased abruptly after VitD3. The expression of CD18, CD32, and CD64 increased during differentiation with all three agents. Apoptosis remained less than 10% until day 3 but increased after differentiation by DMF or ATRA. Differentiation with ATRA or VitD3 increased the respiratory burst after day 4. DMF differentiation showed a high OPKA titer at day 1 which sustained thereafter while ATRA or VitD3-differentiated cells gradually increased. Pearson analysis between the phenotypic changes and OPKA titers suggests that CD11c might be a useful differentiation marker for HL-60 cells for use in pneumococcal OPKA.

MeSH Terms

-

Antibodies, Bacterial/immunology

Antigens, CD11c/metabolism

Antigens, CD14/metabolism

Antigens, CD18/metabolism

Apoptosis/*immunology

Biological Assay

Cell Differentiation

Cell Line, Tumor

Cholecalciferol/pharmacology

Dimethylformamide/pharmacology

Flow Cytometry

HL-60 Cells

Humans

Phagocytosis/*immunology

Pneumococcal Vaccines/*immunology

Receptors, IgG/metabolism

Receptors, Immunologic/*biosynthesis

Respiratory Burst/immunology

Streptococcus pneumoniae/*immunology

Tretinoin/pharmacology

Antibodies, Bacterial

Antigens, CD11c

Antigens, CD14

Antigens, CD18

Cholecalciferol

Dimethylformamide

Pneumococcal Vaccines

Receptors, IgG

Receptors, Immunologic

Tretinoin

Figure

Reference

-

1. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989; 38:64–68. 73–76.2. Fedson DS, Musher DM. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. In : Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, editors. Vaccines. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Pa: Saunders;2004.3. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Lexau C, Reingold A, Lefkowitz L, Cieslak PR, Cetron M, Zell ER, et al. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1917–1924.4. Tan TQ. Antibiotic resistant infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: impact on therapeutic options and clinical outcome. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003; 16:271–277.5. Siber GR. Pneumococcal disease: prospects for a new generation of vaccines. Science. 1994; 265:1385–1387.6. Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, Elvin L, Ensor KM, Hackell J, Siber G, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000; 19:187–195.7. Lee LH, Lee CJ, Frasch CE. Development and evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: clinical trials and control tests. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2002; 28:27–41.8. Puumalainen T, Zeta-Capeding MR, Käyhty H, Lucero MG, Auranen K, Leroy O, Nohynek H. Antibody response to an eleven valent diphtheria- and tetanus-conjugated pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Filipino infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002; 21:309–314.9. Wernette CM, Frasch CE, Madore D, Carlone G, Goldblatt D, Plikaytis B, Benjamin W, Quataert SA, Hildreth S, Sikkema DJ, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantitation of human antibodies to pneumococcal polysaccharides. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003; 10:514–519.10. Coughlin RT, White AC, Anderson CA, Carlone GM, Klein DL, Treanor J. Characterization of pneumococcal specific antibodies in healthy unvaccinated adults. Vaccine. 1998; 16:1761–1767.11. Yu X, Sun Y, Frasch C, Concepcion N, Nahm MH. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide preparations may contain non-C-polysaccharide contaminants that are immunogenic. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999; 6:519–524.12. Romero-Steiner S, Libutti D, Pais LB, Dykes J, Anderson P, Whitin JC, Keyserling HL, Carlone GM. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997; 4:415–422.13. Graziano RF, Ball ED, Fanger MW. The expression and modulation of human myeloid-specific antigens during differentiation of the HL-60 cell line. Blood. 1983; 61:1215–1221.14. Hassan HT, Rees JK. Triple combination of retinoic acid, low concentration of cytarabine and dimethylformamide induces differentiation of human acute myeloid leukaemic blasts. Chemotherapy. 1990; 36:51–57.15. Atkinson JP, Jones EA. Biosynthesis of the human C3b/C4b receptor during differentiation of the HL-60 cell line. Identification and characterization of a precursor molecule. J Clin Invest. 1984; 74:1649–1657.16. Collins SJ, Ruscetti FW, Gallagher RE, Gallo RC. Terminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells induced by dimethyl sulfoxide and other polar compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978; 75:2458–2462.17. Trayner ID, Bustorff T, Etches AE, Mufti GJ, Foss Y, Farzaneh F. Changes in antigen expression on differentiating HL60 cells treated with dimethylsulphoxide, all-trans retinoic acid, α1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 or 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate. Leuk Res. 1998; 22:537–547.18. Breitman TR, Selonick SE, Collins SJ. Induction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980; 77:2936–2940.19. Kanayasu-Toyoda T, Yamaguchi T, Uchida E, Hayakawa T. Commitment of neutrophilic differentiation and proliferation of HL-60 cells coincides with expression of transferrin receptor. Effect of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on differentiation and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274:25471–25480.20. Drayson MT, Michell RH, Durham J, Brown G. Cell proliferation and CD11b expression are controlled independently during HL60 cell differentiation initiated by 1,25 α-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) or all-trans-retinoic acid. Exp Cell Res. 2001; 266:126–134.21. Murao S, Gemmell MA, Callaham MF, Anderson NL, Huberman E. Control of macrophage cell differentiation in human promyelocytic HL-60 leukemia cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 1983; 43:4989–4996.22. Zinzar S, Ohnuma T, Holland JF. Effects of simultaneous and sequential exposure to granulocytic and monocytic inducers on the choice of differentiation pathway in HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells. Leuk Res. 1989; 13:23–30.23. Collins SJ, Ruscetti FW, Gallagher RE, Gallo RC. Normal functional characteristics of cultured human promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60) after induction of differentiation by dimethylsulfoxide. J Exp Med. 1979; 149:969–974.24. Underhill DM, Ozinsky A. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002; 20:825–852.25. Miller LJ, Schwarting R, Springer TA. Regulated expression of the Mac-1, LFA-1, p150,95 glycoprotein family during leukocyte differentiation. J Immunol. 1986; 137:2891–2900.26. Kim HS, Kim KH, Kim GH, Seoh JY. Fcγ Receptor and Mac-1 Expression and Functional Differentiation of HL-60 Cells by All-trans Retinoic Acid. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1999; 42:462–471.27. Jansen WT, Breukels MA, Snippe H, Sanders LA, Verheul AF, Rijkers GT. Fcγ receptor polymorphisms determine the magnitude of in vitro phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae mediated by pneumococcal conjugate sera. J Infect Dis. 1999; 180:888–891.28. Kim HS, Kim KH, Kim GH, Seoh JY. Functional differentiation of HL-60 cells by dimethylsulfoxide and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1999; 42:355–363.29. Martinez JE, Romero-Steiner S, Pilishvili T, Barnard S, Schinsky J, Goldblatt D, Carlone GM. A flow cytometric opsonophagocytic assay for measurement of functional antibodies elicited after vaccination with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999; 6:581–586.30. Fleck RA, Athwal H, Bygraves JA, Hockley DJ, Feavers IM, Stacey GN. Optimization of nb-4 and hl-60 differentiation for use in opsonophagocytosis assays. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2003; 39:235–242.31. Esposito AL, Clark CA, Poirier WJ. An assessment of the factors contributing to the killing of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. APMIS. 1990; 98:111–121.32. Lortan JE, Kaniuk AS, Monteil MA. Relationship of in vitro phagocytosis of serotype 14 Streptococcus pneumoniae to specific class and IgG subclass antibody levels in healthy adults. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993; 91:54–57.33. Obaro SK, Henderson DC, Monteil MA. Defective antibody-mediated opsonisation of S. pneumoniae in high risk patients detected by flow cytometry. Immunol Lett. 1996; 49:83–89.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Fcr Receptor and Mac-1 Expression and Functional Differentiation of HL-60 Cells by All-trans Retinoic Acid

- Functional Differentiation of HL-60 Cells by Dimethylsulfoxide and Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- Evaluation of antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccines with ELISA and opsonophagocytic assay

- Phenotypic and Functional Differentiation of Promyelocytic Cell Line HL-60 by N-N-dimethylformamide

- Functional Immunity to Cross-Reactive Serotype 6A Induced by Serotype 6B in Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine