J Bacteriol Virol.

2007 Dec;37(4):213-224. 10.4167/jbv.2007.37.4.213.

Comparison of Proteome Component of Helicobacter pylori in Different Atmospheric CO2 Concentration

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, Gyeonsang National University, Jinju, Gyeong-nam 660-751, Republic of Korea. kangssi@gnu.kr

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Gyeonsang National University, Jinju, Gyeong-nam 660-751, Republic of Korea.

- 3Department of Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeonsang National University, Jinju, Gyeong-nam 660-751, Republic of Korea.

- 4Research Institute of Life Science, Gyeonsang National University, Jinju, Gyeong-nam 660-701, Republic of Korea.

- 5Central Laboratory, Gyeonsang National University, Jinju, Gyeong-nam 660-701, Republic of Korea.

- KMID: 1513580

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2007.37.4.213

Abstract

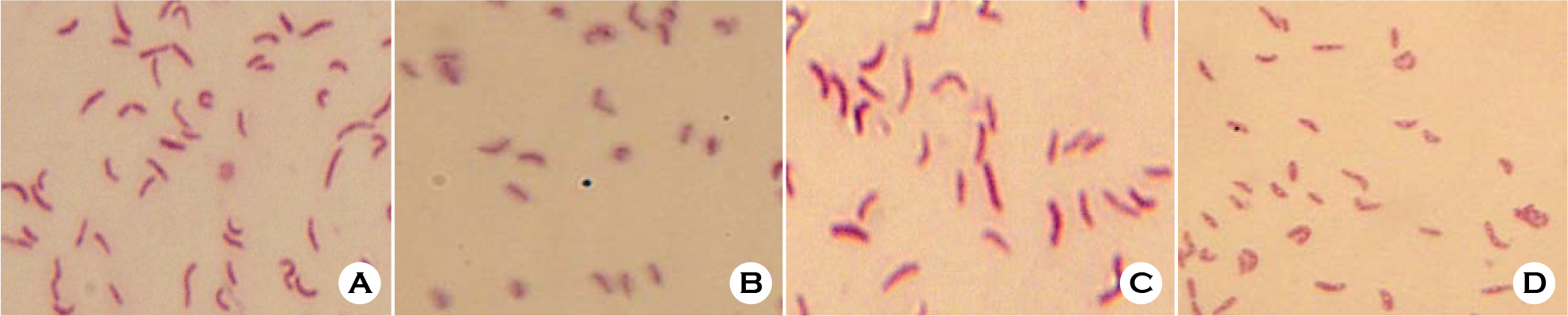

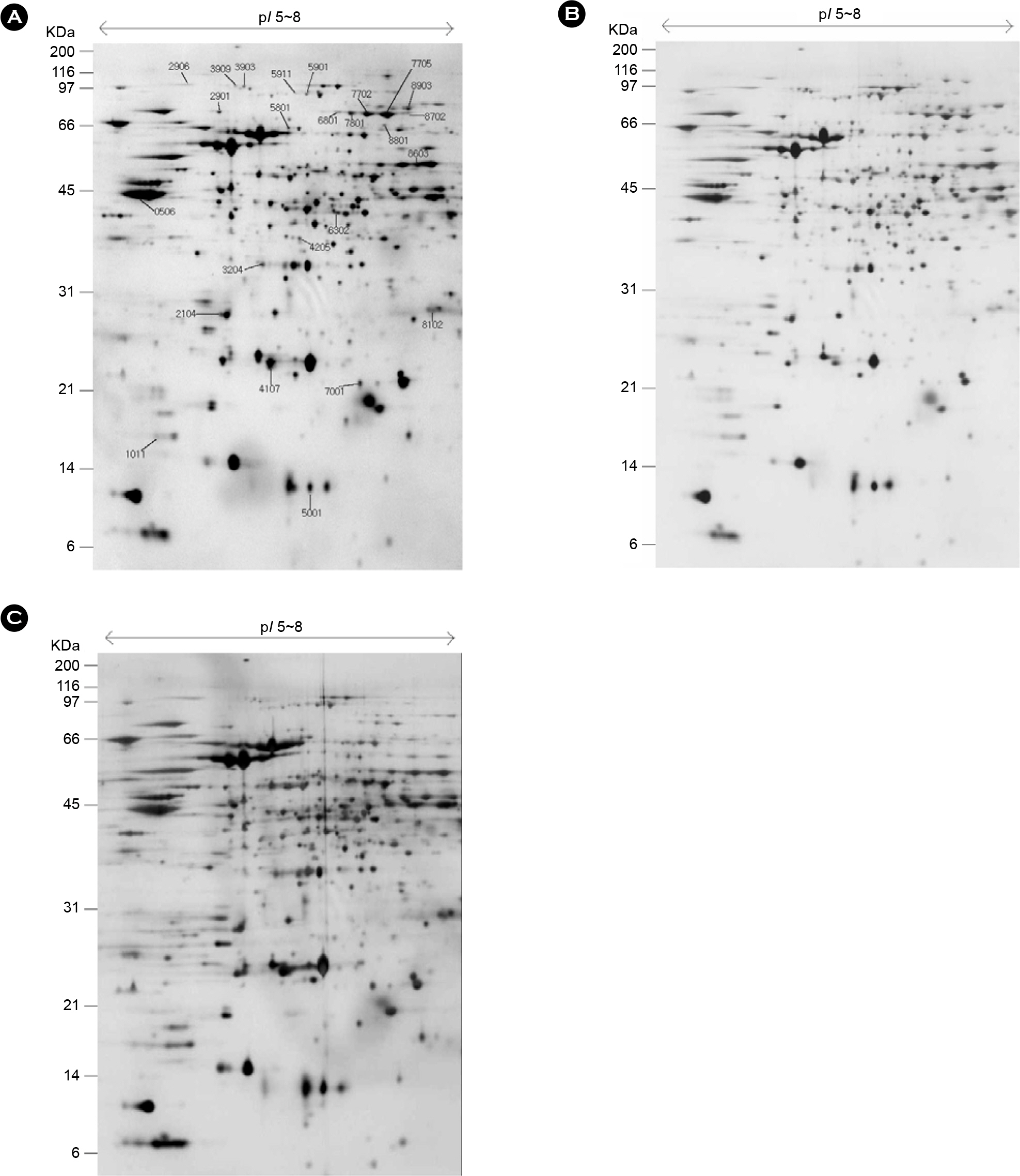

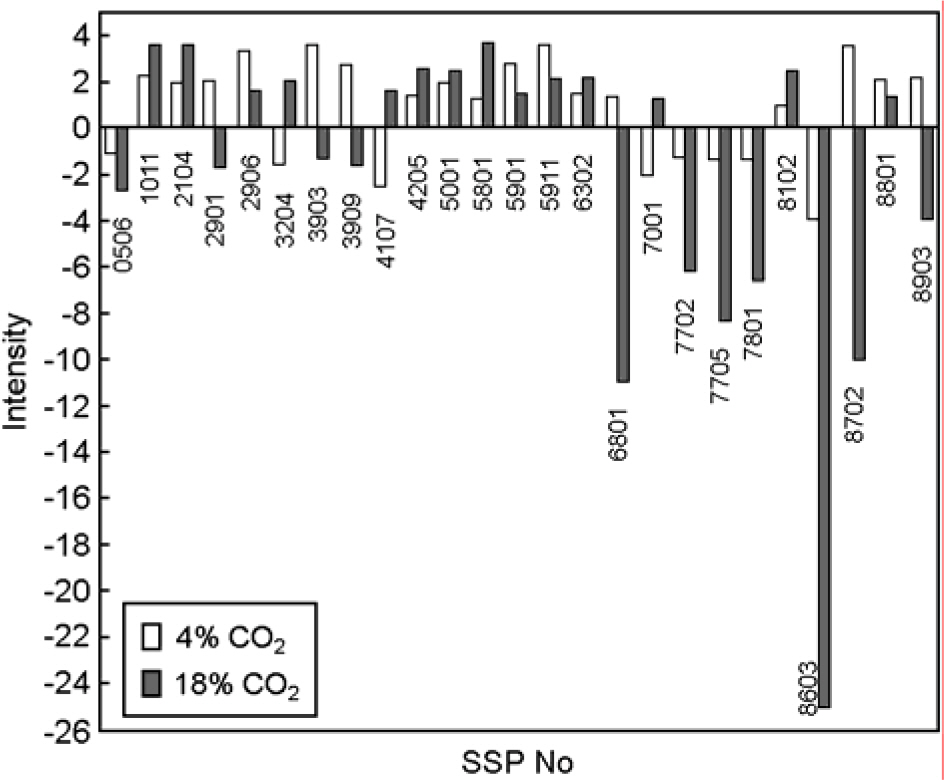

- Helicobacter pylori is a spiral, slow growing gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium. It has been shown to be the etiological agent of gastroduodenal diseases, such as chronic gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and gastric cancer. General culture condition of H. pylori is 5% O2, 10% CO2 and 100% humid atmosphere. We have compared proliferation protein expression profile of H. pylori incubated under normal microaerophilic (10% CO2) and environment stress (4% CO2, 18% CO2) conditions. H. pylori cultured under environment stress displayed coccoid morphology and timedependent decrease in proliferation. We have further compared the protein expression profiles of H. pylori under normal growing and environment stress conditions by a global proteomic analysis, which includes high-resolution 2-DE followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight and nanoelectrospray/tandem mass spectrometry. In total, 42 protein spots were found to be up- or down-regulated by more than 2-fold under environment stress conditions. Of the 42 protein spots processed, 27 spots were identified; they represented 19 genes, including 2 kinds of hypothetical proteins.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1). 이광호, 조명제, 김종배, 최상경, 김영채. 위내시경 생 검체에서 분리한 Campylobacter pylori의 미생물학적 특 성. 대한미생물학회지 Campylobacter pylori. 23:17–26. 1988.2). 이광호, 조명제, 김종배, 최상경, 박철근, 김영채, 최진 학, 최국진. 위십이지장 염증성 질환과 Campylobacter pylori에 관한 전향적 연구. 대한미생물학회지. 23:9–16. 1988.3). Akada JK, Shirai M, Takeuchi H, Tsuda M, Nakazawa T. Identification of the urease operon in Helicobacter pylori and its control by mRNA decay in response to pH. Mol Microbiol. 36:1071–1084. 2000.4). Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, King BL, Brown ED, Doig PC, Smith DR, Noonan B, Guild BC, Dejonge BL, Carmel G, Tummino PJ, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills DM, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills SD, Jiang Q, Taylor DE, Vovis GF, Trust TJ. Genomicsequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 397:176–180. 1999.5). Back HY, Lim JW, Kim HY, Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim KH. Oxidative-stress-related proteome changes in Helicobacter pylori-infectied human gastric mucosa. J Biochem. 397:291–299. 2004.6). Bail SC, Kim KM, Song SM, Kim DS, Jun JS, Lee SG, Song JY, Park JU, Kang HL, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Youn HS, Ko GH, Rhee KH. Proteomic analysis of the sarcosine-insoluble outer membrane fraction of Helicobacter pylori strain 26695. J Bacteriol. 186:949–955. 2004.7). Bearson S, Bearson B, Foster JW. Acid stress responses in enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 147:173–180. 1997.

Article8). Beier D, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Identification and characterization of an operon of Helicobacter pylori that is involved in motility and stress adaptation. J Bacteriol. 179:4676–4683. 1997.9). Bereswill S, Greiner S, van Vliet AH, Waidner B, Fassbinder F, Schiltz E, Kusters JG, Kist M. Regulation of Ferritin-Mediated Cytoplasmic Iron Storage by the Ferric Uptake Regulator Homolog (Fur) of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 182:5948–5953. 2000.10). Bereswill S, Lichte F, Greiner S, Waidner B, Fassbinder F, Kist M. The ferric uptake regulator (Fur) homologue of Helicobacter pylori: functional analysis of the coding gene and controlled production of the recombinant protein in Escherichia coli. Med Microbiol Immunol. 188:31–40. 1999.11). Bereswill S, Lichte F, Vey T, Fassbinder F, Kist M. Cloning and characterization of the fur gene from Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 159:193–200. 1998.12). Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori; its role in disease. Clin Infect Dis. 15:386–392. 1992.13). Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 72:248–254. 1976.

Article14). Bukau B. Regulation of the Escherichia coli heatshock response. Mol Microbiol. 9:671–680. 1993.15). Burns BP, Hazell SL, Mendz GL. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity in Helicobacter pylori and the requirement of increased CO2 for growth. Microbiology. 141:3113–3118. 1995.16). Chuang MH, Wu MS, Lin JT, Chiou SH. Proteomic analysis of proteins expressed by Helicobacter pylori under oxidative stress. Proteomics. 5:3895–3901. 2005.17). Collins CM, Falkow S. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli urease genes: evidence for two distinct loci. J Bacteriol. 172:7138–7144. 1990.18). Cussac V, Richard L, Ferrero , Labigne A. Exression of Helicobacter pylori urease genes in Escherichia coli grown under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J Bacterial. 174:2466–2473. 1992.19). de Vries N, van Ark EM, Stoof J, Kuipers EJ, van Vliet AH, Kusters JG. The stress-induced hsp12 gene shows genetic variation among Helicobacter pylori strains. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 38:45–51. 2003.20). Donovan WP, Kushner SR. Polynucleotide phosphorylase and ribonuclease II are required for cell viability and mRNA turnover in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 83:120–124. 1986.21). Foynes S, Dorrell N, Ward SJ, Stabler RA, McColm AA, Rycroft AN, Wren BW. Helicobacter pylori possesses two CheY response regulators and a histidine kinase sensor, CheA, which are essential for chemotaxis and colonization of the gastric mucosa. Infect Immun. 68:2016–2023. 2000.22). Hengge-Aronis R. Back to log phase. sigma S as a global regulator in the osmotic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 21:887–893. 1996.23). Heukeshoven J, Dernick R. Improved silver staining of sodiumdodecyl sulfate gels. Electrophoresis. 9:28–32. 1988.24). Holmgren A. Reduction of disulfides by thioredoxin. Exceptional reactivity of insulin and suggested functions of thioredoxin in mechanism of hormone action. J Biol Chem. 254:9113–9119. 1979.

Article25). Homuth G, Domm S, Kleiner D, Schumann W. Transcriptional analysis of major heat shock genes of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 182:4257–4263. 2000.26). Huesca M, Goodwin A, Bhagwansingh A, Hoffman P, Lingwood CA. Characterization of an acidic-pH-inducible stress protein (hsp70), a putative sulfatide binding adhesin, from Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 66:4061–4067. 1998.27). Karita M, Tummuru MK, Wirth HP, Blaser MJ. Effect of growth phase and acid shock on Helicobacter pylori cagA expression. Infect Immun. 64:4501–4507. 1996.28). Langenberg ML, Tytgat GN, Schipper ME, Rietra PJ, Zanen HC. Campylobacter-like organisms in the stomach of patients and healthy individuals. Lancet. i:1348–1349. 1984.29). Lee MH, Mulrooney SB, Renner MJ, Markowicz Y, Hausinger RP. Klebsiella aerogenes urease gene cluster: sequence of ureD and demonstration that four accessory genes (ureD, ureE, ureF, urge) are involved in nickel metallocenter biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 174:4324–4330. 1992.30). Lee S, Sowa ME, Tsai TF. Structure of the ClpB molecular chaperone. Life Sciences. 2:pp:. 68. 2004.31). Lee S, Sowa ME, Watanabe YH, Sigler PB, Chiu W, Yoshida M, Tsai FT. The structure of ClpB: a molecular chaperone that rescues proteins from an aggregated state. Cell. 115:229–240. 2003.32). Litwin CM, Calderwood SB. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 6:137–49. 1993.

Article33). Marshell BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. i:1311–1314. 1984.34). Matsukawa Y, Asai Y, Kitamura N, Sawada S. Exacerbation of rheumatoid arthritis following Helicobacter pylori eradication: disruption of established oral tolerance against heat shock protein? Med Hypotheses. 64:41–43. 2005.35). McGowan CC, Necheva A, Thompson SA, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Acid-induced expression of an LPS-associated gene in Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 30:19–31. 1998.36). Mendes MJ, Karmali A, Brown P. One-step affinity purification of urease from jack beans. Biochemie. 70:1369–1371. 1988.

Article37). Mohanty BK, Kushner SR. Polynucleotide phosphorylase functions both as a 30∼50 exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:11966–11971. 2000.38). Musher DM, Griffith DP, Yawn D, Rossen RD. Role of urease in pyelonephritis resulting from urinary tract infection with Proteus. J Infect Dis. 131:177–181. 1975.

Article39). O'connell KL, Stults JT. Identification of mouse liver proteins of two-dimensional electrophoresis gel by matrix-assisted larser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of in situ enzymatic digests. Electrophoresis. 18:349–359. 1997.40). O'Farrell PH. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 250:4007–4021. 1975.41). Olczak AA, Seyler RW, Olson JW, Maier RJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori antioxidant activities with host colonization proficiency. Infec Immun. 71:580–583. 2003.42). Petersen AM, Krogfelt KA. Helicobacter pylori: an invading microorganism? A review. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 36:117–126. 2003.43). Reynolds CM, Poole LB. Activity of one of two engineered heterodimers of AhpF, the NADPH:peroxiredoxin oxidoreductase from Salmonella typhimurium, reveals intrasubnit electron transfer between domains. Biochemistry. 40:3912–3919. 2001.44). Richard W, Seyler JR, Jonathan WO, Robert JM. Super-oxide dismutase-deficient mutants of Helicobacter pylori are hypersensitive to oxidative stress and defective in host colonization. Infect Immun. 69:4034–4040. 2001.45). Shin M, Arnon DI. Enzymic mechanisms of pyridine nucleotide reduction chloroplasts. J Biol Chem. 240:1405–1411. 1965.46). Small P, Blankenhorn D, Welty D, Zinser E, Slonczewski JL. Acid and base resistance in Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri: role of rpoS and growth pH. J Bacteriol. 176:1729–1737. 1994.47). Spohn G, Scarlato V. Motility of Helicobacter pylori is coordinately regulated by the transcriptional activator FlgR, an NtrC homolog. J Bacteriol. 181:593–599. 1999.48). Spohn G, Scarlato V. The autoregulatory HspR repressor protein governs chaperone gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 34:663–674. 1999.49). Stead D, Park SF. Roles of Fe superoxide dismutase and catalase in resistance of Campylobacter coli to freeze- thaw stress. Appl Environ Micobiol. 66:3110–3112. 2000.50). Syldatk C, May O, Altenbuchner J, Mattes R, Siemann M. Microbial hydantoinases-industrial enzymes from the origin of life? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 51:293–309. 1999.51). Wang G, Alamuri P, Maier RJ. The diverse antioxidant systems of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 61:847–860. 2006.52). Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 28:32–40. 2003.

Article53). Worst DJ, Otto BR, de Graaff J. Iron-repressible outer membrane proteins of Helicobacter pylori involved in heme uptake. Infect Immun. 63:4161–4165. 1995.54). Yeo M, Park HK, Kim DK, Cho SW. Restoration of heat shock protein70 suppresses gastric mucosal inducible nitric oxide synthase expression induced by Helicobacter pylori. Proteomics. 4:3335–3342. 2004.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Proteomics Approach in Helicobacter pylori Researches

- Response to Treatment of Helicobacter pylori-associated Dyspepsia: Eradication of Helicobacter pylori or Correction of Gastric or Intestinal Dysbiosis?

- Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in functional dyspepsia

- Helicobacter pylori Infection and Cardiovascular Disease

- Purification of the urease of helicobacter pylori and production of monoclonal antibody to the urease of helicobacter pylori