J Korean Surg Soc.

2010 Jul;79(1):1-7. 10.4174/jkss.2010.79.1.1.

Immunohistochemical Expression of Stem Cell Markers during the Wound Healing Process of Cutaneous Burn

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 2Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 3Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea. biogra@hallym.or.kr

- KMID: 1455480

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4174/jkss.2010.79.1.1

Abstract

- PURPOSE

A cutaneous wound healing requires a well-orchestrated integration of the complex biological and molecular events of cell migration and proliferation, extracellular matrix deposition, angiogenesis and remodeling. Finally, skin regeneration is the main goal. Stem cells are self-renewing multipotent progenitors with the broadest developmental potential in a given tissue at a given time. The aim of this study was to examine the role of stem cells during the wound healing process of cutaneous burn in hairless mice by using immunohistochemical stainings (nestin, cytokeratin 15 and CD31).

METHODS

Each mouse received 2 burns at the dorsal area by applying a metal stick heated in boiling water. Burn wound sites were dressed with duoderm. The mice were sacrificed at 0, 2, 7, 14 and 21 days after burn. Histological findings and immunohistochemical expression for stem cell markers were observed.

RESULTS

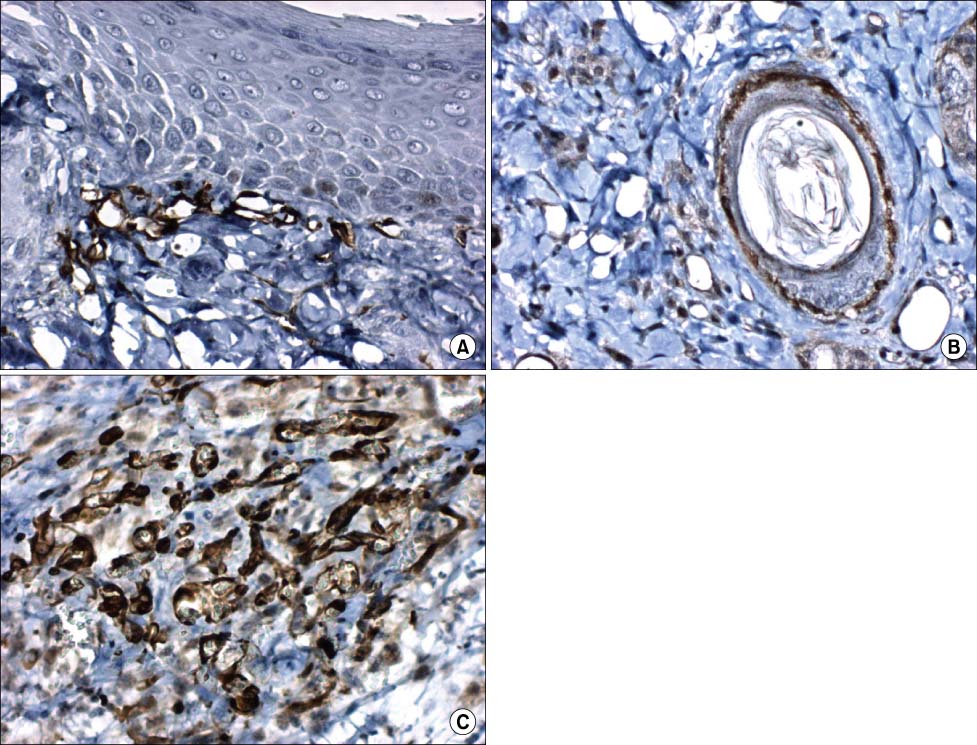

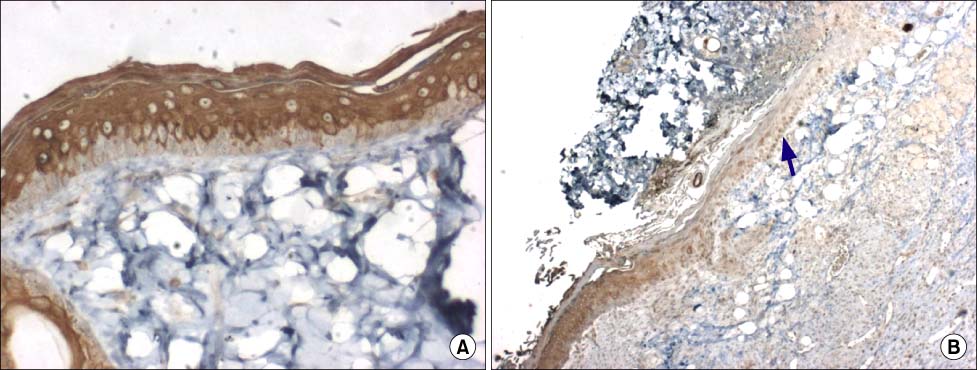

Nestin was expressed in the stromal cells beneath the epidermis, hair follices, dermal cysts and endothelial cells. Cytokeratin 15 was expressed in the epidermis except in basal cells. On 7 and 14 days after burn, the regenerated epidermis didn't express cytokeratin 15. CD31 was expressed in the endothelial cells on 7 and 14 days after burn. The amount of nestin expression was the highest.

CONCLUSION

Our results showed that nestin may have various effects on burn wound healing. Cytokeratin 15 was expressed before burn and after burn. It is likely that other cytokeratin may stimulate epithelial regeneration. CD31 may act in vascular regeneration during burn healing.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Animals

Bandages, Hydrocolloid

Burns

Cell Movement

Endothelial Cells

Epidermis

Extracellular Matrix

Hair

Hot Temperature

Intermediate Filament Proteins

Keratin-15

Keratins

Mice

Mice, Hairless

Nerve Tissue Proteins

Regeneration

Skin

Stem Cells

Stromal Cells

Water

Wound Healing

Intermediate Filament Proteins

Keratin-15

Keratins

Nerve Tissue Proteins

Water

Figure

Reference

-

1. Zhu H, Wei X, Bian K, Murad F. Effects of nitric oxide on skin burn wound healing. J Burn Care Res. 2008. 29:804–814.2. Benavides F, Oberyszyn TM, VanBuskirk AM, Reeve VE, Kusewitt DF. The hairless mouse in skin research. J Dermatol Sci. 2009. 53:10–18.3. Li L, Mignone J, Yang M, Matic M, Penman S, Enikolopov G, et al. Nestin expression in hair follicle sheath progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003. 100:9958–9961.4. Morris RJ, Liu Y, Marles L, Yang Z, Trempus C, Li S, et al. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004. 22:411–417.5. Amoh Y, Li L, Yang M, Moossa AR, Katsuoka K, Penman S, et al. Nascent blood vessels in the skin arise from nestin-expressing hair-follicle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004. 101:13291–13295.6. Amoh Y, Li L, Katsuoka K, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Multipotent nestin-positive, keratin-negative hair-follicle bulge stem cells can form neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005. 102:5530–5534.7. Webb A, Li A, Kaur P. Location and phenotype of human adult keratinocyte stem cells of the skin. Differentiation. 2004. 72:387–395.8. Porter RM, Lunny DP, Ogden PH, Morley SM, McLean WH, Evans A, et al. K15 expression implies lateral differentiation within stratified epithelial basal cells. Lab Invest. 2000. 80:1701–1710.9. Werner S, Munz B. Suppression of keratin 15 expression by transforming growth factor beta in vitro and by cutaneous injury in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 2000. 254:80–90.10. Ross EA, Freeman S, Zhao Y, Dhanjal TS, Ross EJ, Lax S, et al. A novel role for PECAM-1 (CD31) in regulating haematopoietic progenitor cell compartmentalization between the peripheral blood and bone marrow. PLoS One. 2008. 3:e2338.11. Nogami M, Hoshi T, Arai T, Toukairin Y, Takama M, Takahashi I. Morphology of lymphatic regeneration in rat incision wound healing in comparison with vascular regeneration. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009. 11:213–218.12. Shimamura K, Nakatani T, Ueda A, Sugama J, Okuwa M. Relationship between lymphangiogenesis and exudates during the wound-healing process of mouse skin full-thickness wound. Wound Repair Regen. 2009. 17:598–605.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Wound Healing Effect of a Silk Fibroin Film on Cutaneous Burn of Hairless Mice

- Fabricating Composite Cell Sheets for Wound Healing: Cell Sheets Based on the Communication Between BMSCs and HFSCs Facilitate Full-Thickness Cutaneous Wound Healing

- Effective Delivering Method of Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Cells in Cutaneous Wound Healing

- Acceleration of Wound Regeneration by Implantation of CD34-Mononuclear Cell from Human Cord Blood

- The Distribution of CD44 in Wound Healing of Rabbit Alkali Burn