Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2018 Jul;22(4):427-436. 10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.4.427.

Concurrent treatment with ursolic acid and low-intensity treadmill exercise improves muscle atrophy and related outcomes in rats

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Sports Science, College of Natural Science, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju 54896, Korea. sh5275@jbnu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Physiology, Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease Center, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea.

- 3Department of Leisure Sport, Kyungpook National University, Sangju 37224, Korea. prescript@knu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2414267

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.4.427

Abstract

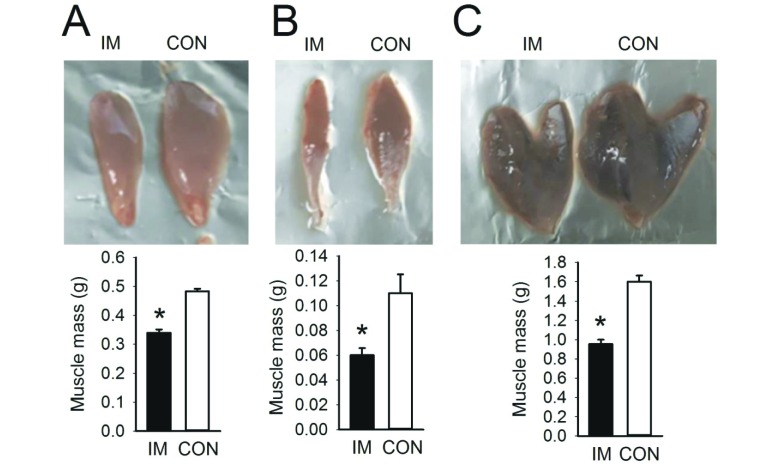

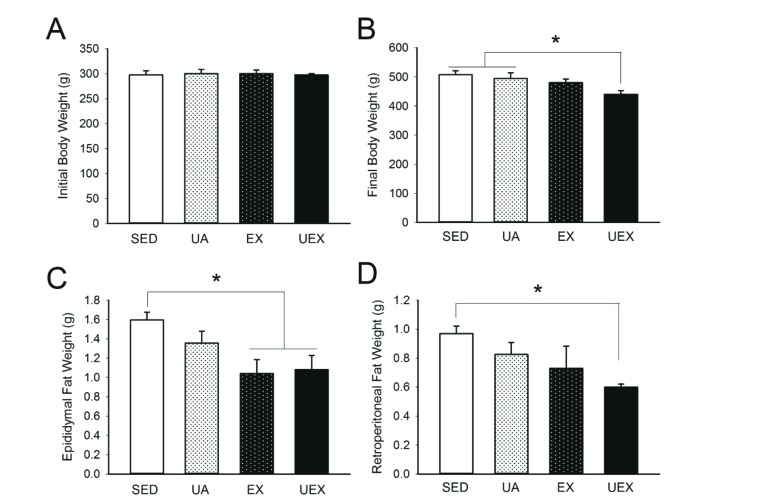

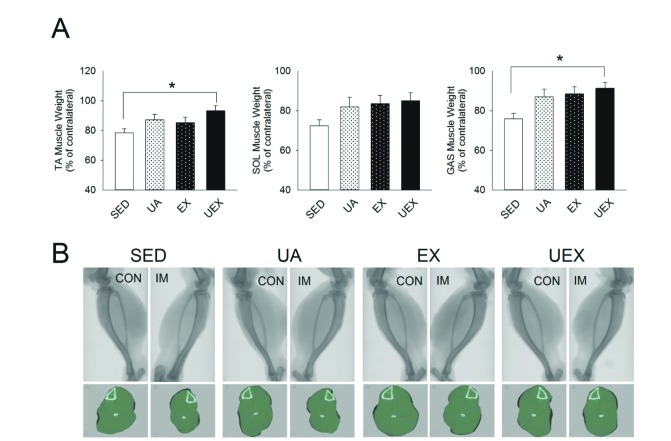

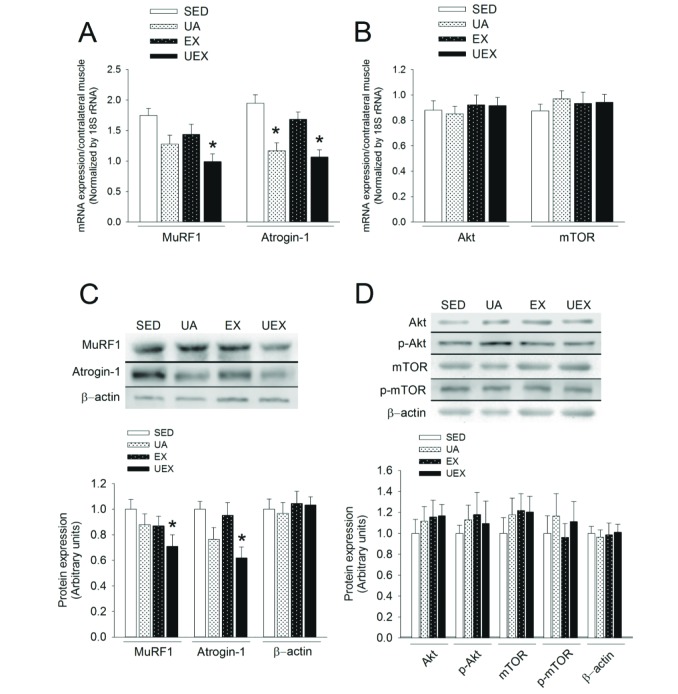

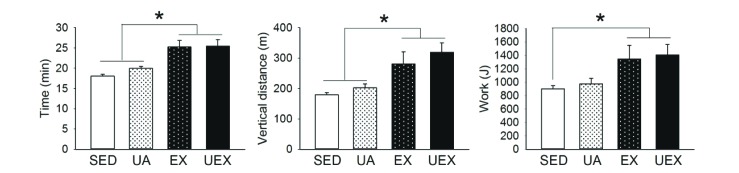

- The objective of this study was to analyze the concurrent treatment effects of ursolic acid (UA) and low-intensity treadmill exercise and to confirm the effectiveness of UA as an exercise mimetic to safely improve muscle atrophy-related diseases using Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats with skeletal muscle atrophy. Significant muscle atrophy was induced in male SD rats through hind limb immobilization using casting for 10 days. The muscle atrophy-induced SD rats were group into four: SED, sedentary; UA, daily intraperitoneal UA injection, 5 mg/kg; EX, low-intensity (10-12 m/min, 0° grade) treadmill exercise; and UEX, daily intraperitoneal UA injection, 5 mg/kg, and low-intensity (10-12 m/min, 0° grade) treadmill exercise. After 8 weeks of treatment, endurance capacity was analyzed using a treadmill, and tissues were extracted for analysis of visceral fat mass, body weight, muscle mass, expression of muscle atrophy- and hypertrophy-related genes, and endurance capacity. Although the effects of body weight gain control, muscle mass increase, and endurance capacity improvement were inadequate in the UA group, significant results were confirmed in the UEX group. The UEX group had significantly reduced body weight and visceral fat, significantly improved mass of tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles, and significantly decreased atrophy-related gene expression of MuRF1 and atrogin-1, but did not have significant change in hypertrophy-related gene expression of Akt and mTOR. The endurance capacity was significantly improved in the EX and UEX groups. These data suggest that concurrent treatment with low-intensity exercise and UA is effective for atrophy-related physical dysfunctions.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ebert SM, Dyle MC, Bullard SA, Dierdorff JM, Murry DJ, Fox DK, Bongers KS, Lira VA, Meyerholz DK, Talley JJ, Adams CM. Identification and small molecule inhibition of an activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)-dependent pathway to age-related skeletal muscle weakness and atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2015; 290:25497–25511. PMID: 26338703.

Article2. Tanaka H, Desouza CA, Jones PP, Stevenson ET, Davy KP, Seals DR. Greater rate of decline in maximal aerobic capacity with age in physically active vs. sedentary healthy women. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1997; 83:1947–1953. PMID: 9390967.3. Feng HZ, Chen M, Weinstein LS, Jin JP. Improved fatigue resistance in Gsα-deficient and aging mouse skeletal muscles due to adaptive increases in slow fibers. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011; 111:834–843. PMID: 21680879.

Article4. Wilson JR, Mancini DM, Dunkman WB. Exertional fatigue due to skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1993; 87:470–475. PMID: 8425294.

Article5. Elkin SL, Williams L, Moore M, Hodson ME, Rutherford OM. Relationship of skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength and bone mineral density in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2000; 99:309–314. PMID: 10995596.

Article6. He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, Papasian CJ, Hu T, Deng HW. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2016; 27:473–482. PMID: 26243357.

Article7. Kim H, Suzuki T, Saito K, Yoshida H, Kojima N, Kim M, Sudo M, Yamashiro Y, Tokimitsu I. Effects of exercise and tea catechins on muscle mass, strength and walking ability in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013; 13:458–465. PMID: 22935006.

Article8. Brotto M, Abreu EL. Sarcopenia: pharmacology of today and tomorrow. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012; 343:540–546. PMID: 22929991.

Article9. Gielen S, Sandri M, Kozarez I, Kratzsch J, Teupser D, Thiery J, Erbs S, Mangner N, Lenk K, Hambrecht R, Schuler G, Adams V. Exercise training attenuates MuRF-1 expression in the skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure independent of age: the randomized Leipzig Exercise Intervention in Chronic Heart Failure and Aging catabolism study. Circulation. 2012; 125:2716–2727. PMID: 22565934.10. Bamman MM, Roberts BM, Adams GR. Molecular regulation of exercise-induced muscle fiber hypertrophy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018; 8:a029751. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029751. PMID: 28490543.

Article11. Lai CC, Tu YK, Wang TG, Huang YT, Chien KL. Effects of resistance training, endurance training and whole-body vibration on lean body mass, muscle strength and physical performance in older people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018; 47:367–373. PMID: 29471456.

Article12. Watanabe Y, Madarame H, Ogasawara R, Nakazato K, Ishii N. Effect of very low-intensity resistance training with slow movement on muscle size and strength in healthy older adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014; 34:463–470. PMID: 24304680.

Article13. Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O'Reilly KP, Knuttgen HG, Evans WJ. Strength conditioning in older men: skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improved function. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988; 64:1038–1044. PMID: 3366726.

Article14. Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA. 1990; 263:3029–3034. PMID: 2342214.

Article15. Daly RM. Exercise and nutritional approaches to prevent frail bones, falls and fractures: an update. Climacteric. 2017; 20:119–124. PMID: 28286988.

Article16. Ruuskanen JM, Ruoppila I. Physical activity and psychological well-being among people aged 65 to 84 years. Age Ageing. 1995; 24:292–296. PMID: 7484485.

Article17. Goodyear LJ. The exercise pill—too good to be true? N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1842–1844. PMID: 18946072.18. Wen CP, Wai JP, Tsai MK, Yang YC, Cheng TY, Lee MC, Chan HT, Tsao CK, Tsai SP, Wu X. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011; 378:1244–1253. PMID: 21846575.

Article19. Gorianovas G, Skurvydas A, Streckis V, Brazaitis M, Kamandulis S, McHugh MP. Repeated bout effect was more expressed in young adult males than in elderly males and boys. Biomed Res Int. 2013; 2013:218970. DOI: 10.1155/2013/218970. PMID: 23484095.

Article20. Lavender AP, Nosaka K. Comparison between old and young men for changes in makers of muscle damage following voluntary eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006; 31:218–225. PMID: 16770348.

Article21. Shishodia S, Majumdar S, Banerjee S, Aggarwal BB. Ursolic acid inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by carcinogenic agents through suppression of IkappaBalpha kinase and p65 phosphorylation: correlation with down-regulation of cyclooxygenase, matrix metalloproteinase 9, and cyclin D1. Cancer Res. 2003; 63:4375–4383. PMID: 12907607.22. Tsai SJ, Yin MC. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory protection of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid in PC12 cells. J Food Sci. 2008; 73:H174–H178. PMID: 18803714.

Article23. Ullevig SL, Zhao Q, Zamora D, Asmis R. Ursolic acid protects diabetic mice against monocyte dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011; 219:409–416. PMID: 21752377.

Article24. Kunkel SD, Suneja M, Ebert SM, Bongers KS, Fox DK, Malmberg SE, Alipour F, Shields RK, Adams CM. mRNA expression signatures of human skeletal muscle atrophy identify a natural compound that increases muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2011; 13:627–638. PMID: 21641545.

Article25. Bang HS, Seo DY, Chung YM, Oh KM, Park JJ, Arturo F, Jeong SH, Kim N, Han J. Ursolic Acid-induced elevation of serum irisin augments muscle strength during resistance training in men. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014; 18:441–446. PMID: 25352765.

Article26. Jeong JW, Shim JJ, Choi ID, Kim SH, Ra J, Ku HK, Lee DE, Kim TY, Jeung W, Lee JH, Lee KW, Huh CS, Sim JH, Ahn YT. Apple pomace extract improves endurance in exercise performance by increasing strength and weight of skeletal muscle. J Med Food. 2015; 18:1380–1386. PMID: 26331671.

Article27. Kunkel SD, Elmore CJ, Bongers KS, Ebert SM, Fox DK, Dyle MC, Bullard SA, Adams CM. Ursolic acid increases skeletal muscle and brown fat and decreases diet-induced obesity, glucose intolerance and fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e39332. PMID: 22745735.

Article28. Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K, Komiya T, Udagawa Y. Ursolic acid induces Bax-dependent apoptosis through the caspase-3 pathway in endometrial cancer SNG-II cells. Oncol Rep. 2005; 13:51–57. PMID: 15583801.

Article29. Choi YH, Baek JH, Yoo MA, Chung HY, Kim ND, Kim KW. Induction of apoptosis by ursolic acid through activation of caspases and down-regulation of c-IAPs in human prostate epithelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2000; 17:565–571. PMID: 10938399.

Article30. Ikeda Y, Murakami A, Ohigashi H. Ursolic acid: an anti- and pro-inflammatory triterpenoid. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008; 52:26–42. PMID: 18203131.

Article31. Cárdenas C, Quesada AR, Medina MA. Effects of ursolic acid on different steps of the angiogenic process. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004; 320:402–408. PMID: 15219842.

Article32. Sohn KH, Lee HY, Chung HY, Young HS, Yi SY, Kim KW. Anti-angiogenic activity of triterpene acids. Cancer Lett. 1995; 94:213–218. PMID: 7543366.

Article33. Coutinho EL, Gomes AR, Franca CN, Salvini TF. A new model for the immobilization of the rat hind limb. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002; 35:1329–1332. PMID: 12426632.

Article34. Vazeille E, Codran A, Claustre A, Averous J, Listrat A, Béchet D, Taillandier D, Dardevet D, Attaix D, Combaret L. The ubiquitin-proteasome and the mitochondria-associated apoptotic pathways are sequentially downregulated during recovery after immobilization-induced muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 295:E1181–E1190. PMID: 18812460.

Article35. Madaro L, Smeriglio P, Molinaro M, Bouché M. Unilateral immobilization: a simple model of limb atrophy in mice. Basic Applied Myology. 2008; 18:149–153.36. Liu B, Liu Y, Yang G, Xu Z, Chen J. Ursolic acid induces neural regeneration after sciatic nerve injury. Neural Regen Res. 2013; 8:2510–2519. PMID: 25206561.37. Kim C, Kim IH, Kim SI, Kim YS, Kang SH, Moon SH, Kim TS, Kim SK. Comparison of the intraperitoneal, retroorbital and per oral routes for F-18 FDG administration as effective alternatives to intravenous administration in mouse tumor models using small animal PET/CT studies. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011; 45:169–176. PMID: 24900000.

Article38. Kondo H, Fujino H, Murakami S, Tanaka M, Kanazashi M, Nagatomo F, Ishihara A, Roy RR. Low-intensity running exercise enhances the capillary volume and pro-angiogenic factors in the soleus muscle of type 2 diabetic rats. Muscle Nerve. 2015; 51:391–399. PMID: 24917153.

Article39. Bedford TG, Tipton CM, Wilson NC, Oppliger RA, Gisolfi CV. Maximum oxygen consumption of rats and its changes with various experimental procedures. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1979; 47:1278–1283. PMID: 536299.

Article40. Kim JC, Park GD, Kim SH. Inhibition of oxidative stress by antioxidant supplementation does not limit muscle mitochondrial biogenesis or endurance capacity in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2017; 63:277–283. PMID: 29225311.

Article41. Copp SW, Davis RT, Poole DC, Musch TI. Reproducibility of endurance capacity and VO2peak in male Sprague-Dawley rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009; 106:1072–1078. PMID: 19213934.

Article42. Park JY, Wang PY, Matsumoto T, Sung HJ, Ma W, Choi JW, Anderson SA, Leary SC, Balaban RS, Kang JG, Hwang PM. p53 improves aerobic exercise capacity and augments skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA content. Circ Res. 2009; 105:705–711. PMID: 19696408.

Article43. Li S, Laher I. Exercise mimetics: running without a road map. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 101:188–190. PMID: 27727454.

Article44. Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008; 134:405–415. PMID: 18674809.45. Handschin C. Caloric restriction and exercise “mimetics”: Ready for prime time? Pharmacol Res. 2016; 103:158–166. PMID: 26658171.

Article46. Craig DM, Ashcroft SP, Belew MY, Stocks B, Currell K, Baar K, Philp A. Utilizing small nutrient compounds as enhancers of exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Front Physiol. 2015; 6:296. PMID: 26578969.

Article47. Fan W, Evans RM. Exercise mimetics: impact on health and performance. Cell Metab. 2017; 25:242–247. PMID: 27889389.

Article48. Stockinger J, Maxwell N, Shapiro D, deCabo R, Valdez G. Caloric restriction mimetics slow aging of neuromuscular synapses and muscle fibers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017; 73:21–28. PMID: 28329051.

Article49. Naseeb MA, Volpe SL. Protein and exercise in the prevention of sarcopenia and aging. Nutr Res. 2017; 40:1–20. PMID: 28473056.

Article50. Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001; 104:531–543. PMID: 11239410.

Article51. Rao VS, de Melo CL, Queiroz MG, Lemos TL, Menezes DB, Melo TS, Santos FA. Ursolic acid, a pentacyclic triterpene from Sambucus australis, prevents abdominal adiposity in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Med Food. 2011; 14:1375–1382. PMID: 21612453.

Article52. Chu X, He X, Shi Z, Li C, Guo F, Li S, Li Y, Na L, Sun C. Ursolic acid increases energy expenditure through enhancing free fatty acid uptake and β-oxidation via an UCP3/AMPK-dependent pathway in skeletal muscle. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015; 59:1491–1503. PMID: 25944715.

Article53. Winder WW. Energy-sensing and signaling by AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2001; 91:1017–1028. PMID: 11509493.

Article54. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005; 1:15–25. PMID: 16054041.

Article55. Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, Fryer LG, Müller C, Carling D, Kahn BB. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002; 415:339–343. PMID: 11797013.

Article56. Ogasawara R, Kobayashi K, Tsutaki A, Lee K, Abe T, Fujita S, Nakazato K, Ishii N. mTOR signaling response to resistance exercise is altered by chronic resistance training and detraining in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013; 114:934–940. PMID: 23372143.

Article57. Ogasawara R, Fujita S, Hornberger TA, Kitaoka Y, Makanae Y, Nakazato K, Naokata I. The role of mTOR signalling in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass in a rodent model of resistance exercise. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:31142. PMID: 27502839.

Article58. Furlanetto R Jr, de Paula Souza A, de Oliveira AA, Nunes PR, Michelin MA, Chica JE, Murta EF, Orsatti FL. Acute resistance exercise reduces increased gene expression in muscle atrophy of ovariectomised arthritic rats. Prz Menopauzalny. 2016; 15:193–201. PMID: 28250722.59. Bakhtiari N, Hosseinkhani S, Tashakor A, Hemmati R. Ursolic acid ameliorates aging-metabolic phenotype through promoting of skeletal muscle rejuvenation. Med Hypotheses. 2015; 85:1–6. PMID: 25976755.

Article60. Arthur ST, Cooley ID. The effect of physiological stimuli on sarcopenia; impact of Notch and Wnt signaling on impaired aged skeletal muscle repair. Int J Biol Sci. 2012; 8:731–760. PMID: 22701343.

Article61. Souza RW, Piedade WP, Soares LC, Souza PA, Aguiar AF, Vechetti-Júnior IJ, Campos DH, Fernandes AA, Okoshi K, Carvalho RF, Cicogna AC, Dal-Pai-Silva M. Aerobic exercise training prevents heart failure-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by anti-catabolic, but not anabolic actions. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e110020. PMID: 25330387.

Article62. Ji LL, Kang C. Role of PGC-1α in sarcopenia: etiology and potential intervention - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015; 61:139–148. PMID: 25502801.63. Lexell J. Human aging, muscle mass, and fiber type composition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995; 50:11–16. PMID: 7493202.64. Eng CM, Smallwood LH, Rainiero MP, Lahey M, Ward SR, Lieber RL. Scaling of muscle architecture and fiber types in the rat hindlimb. J Exp Biol. 2008; 211:2336–2345. PMID: 18587128.

Article65. Ogasawara R, Sato K, Higashida K, Nakazato K, Fujita S. Ursolic acid stimulates mTORC1 signaling after resistance exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 305:E760–E765. PMID: 23900420.

Article66. Church DD, Schwarz NA, Spillane MB, McKinley-Barnard SK, Andre TL, Ramirez AJ, Willoughby DS. l-Leucine increases skeletal muscle IGF-1 but does not differentially increase Akt/mTORC1 signaling and serum IGF-1 compared to ursolic acid in response to resistance exercise in resistance-trained men. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016; 35:627–638. PMID: 27331824.

Article67. Cho YH, Lee SY, Kim CM, Kim ND, Choe S, Lee CH, Shin JH. Effect of loquat leaf extract on muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle function in healthy adults: a randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016; 2016:4301621. DOI: 10.1155/2016/4301621. PMID: 27999607.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Aerobic Exercise Ameliorates Muscle Atrophy Induced by Methylglyoxal via Increasing Gastrocnemius and Extensor Digitorum Longus Muscle Sensitivity

- Effect of Regular Exercise during Recovery Period Following Steroid Treatment on the Atrophied Type II Muscles Induced by Steroid in Young Rats

- Effect of intermittent low-intensity, short duration exercise on Type II muscle of suspended rats

- Treadmill Exercise as a Preventive Measure Against Age-Related Anxiety and Social Behavioral Disorders in Rats: When Is It Worth Starting?

- Effect of Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia on Cardiac Muscle Glycogen Usage during Exercise in Rats