Int J Stem Cells.

2015 Nov;8(2):191-199. 10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.2.191.

A Novel Cell Therapy Method for Recovering after Brain Stroke in Rats

- Affiliations

-

- 1Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. hoseini2010m@gmail.com

- 2Cell & Molecular Medicine Student Research Group, Medical School, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

- 3Stem Cell Laboratory, Department of Anatomy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

- 4Trangenic Technology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

- KMID: 2380813

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.2.191

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

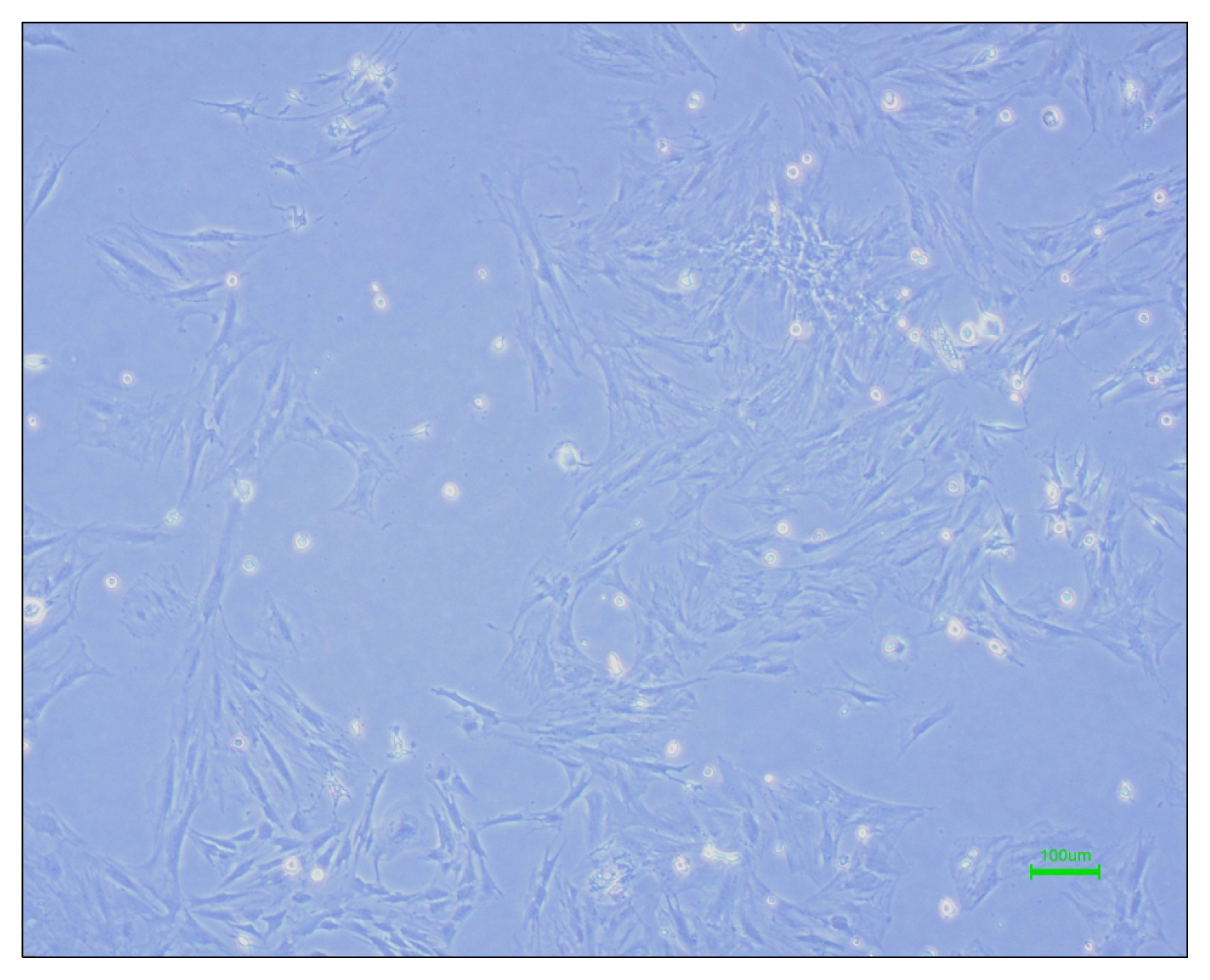

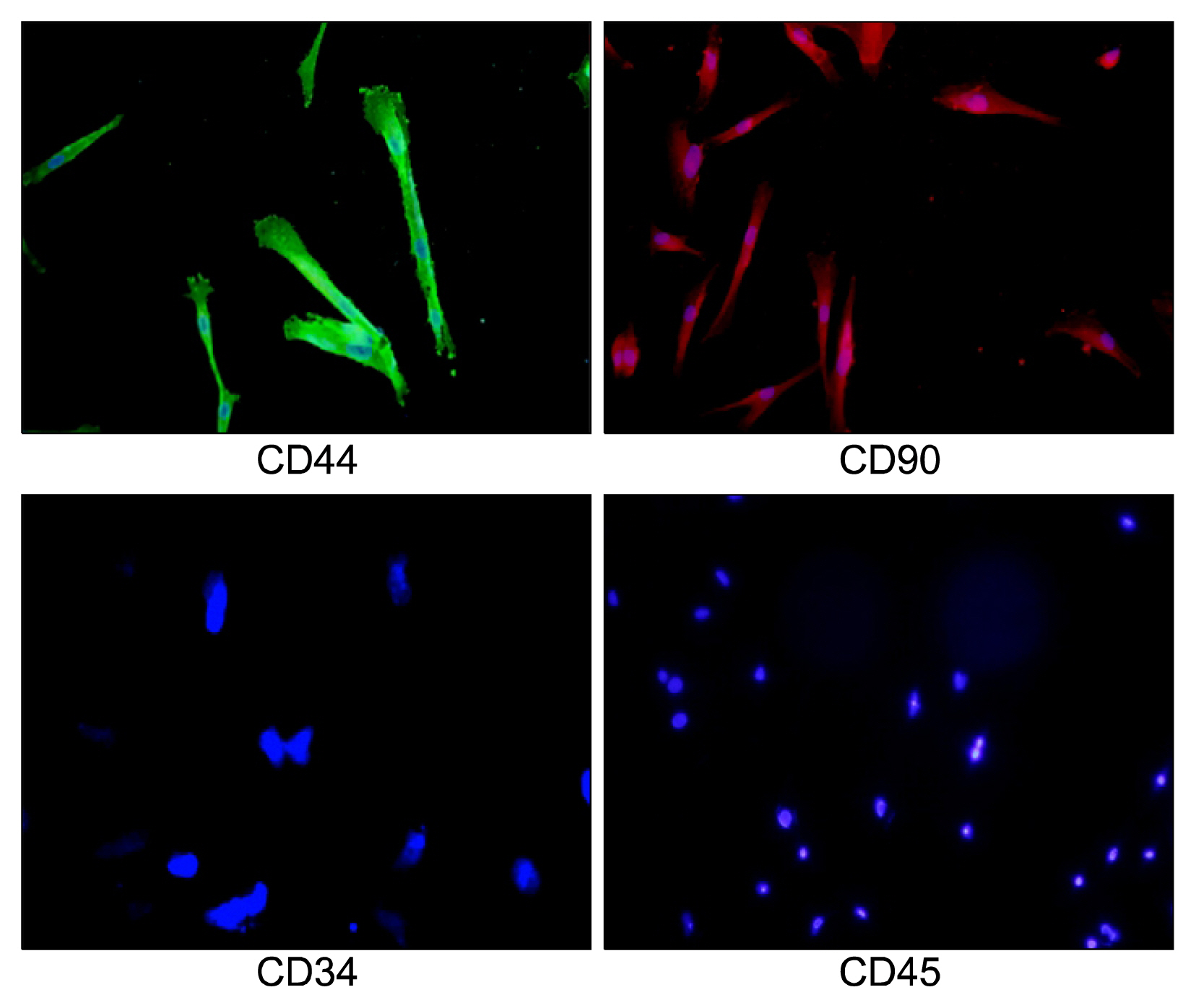

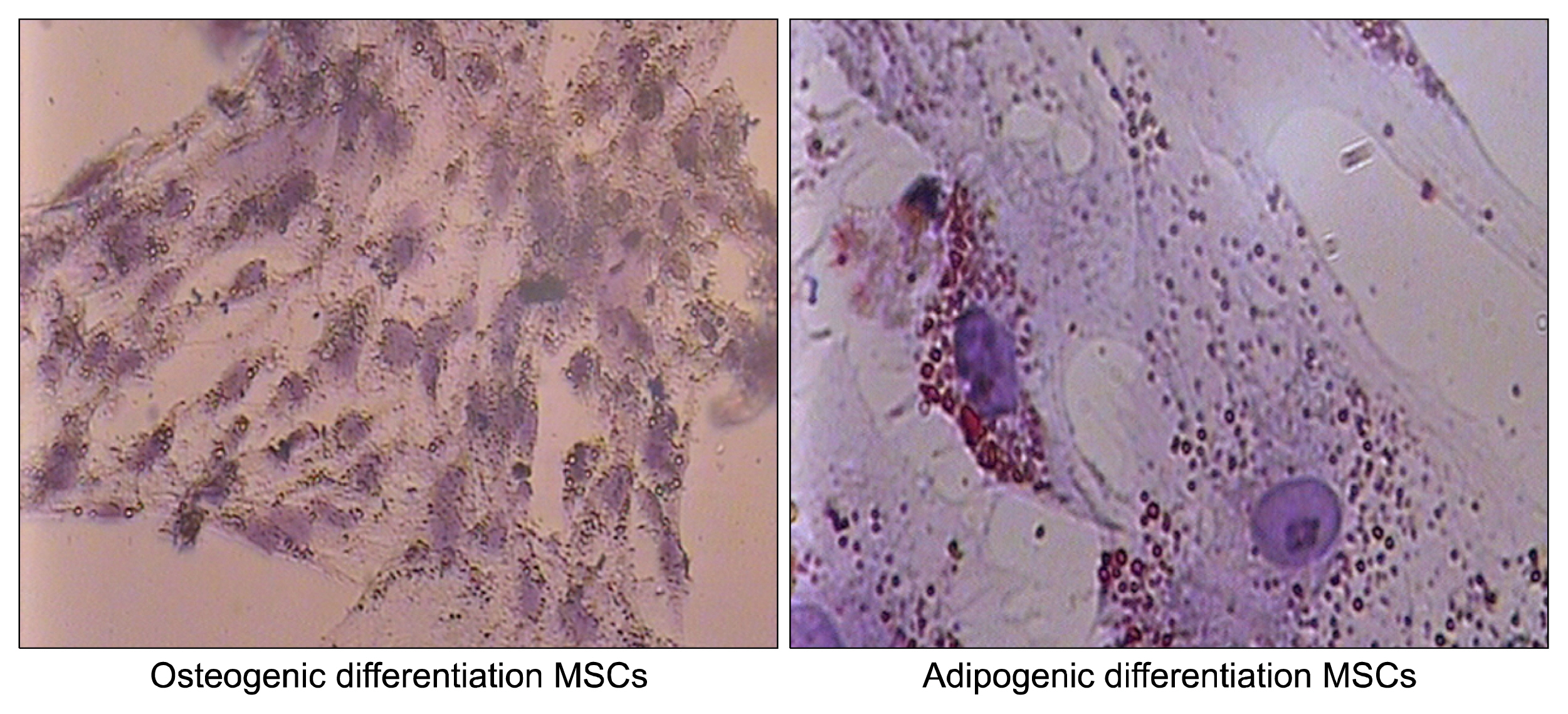

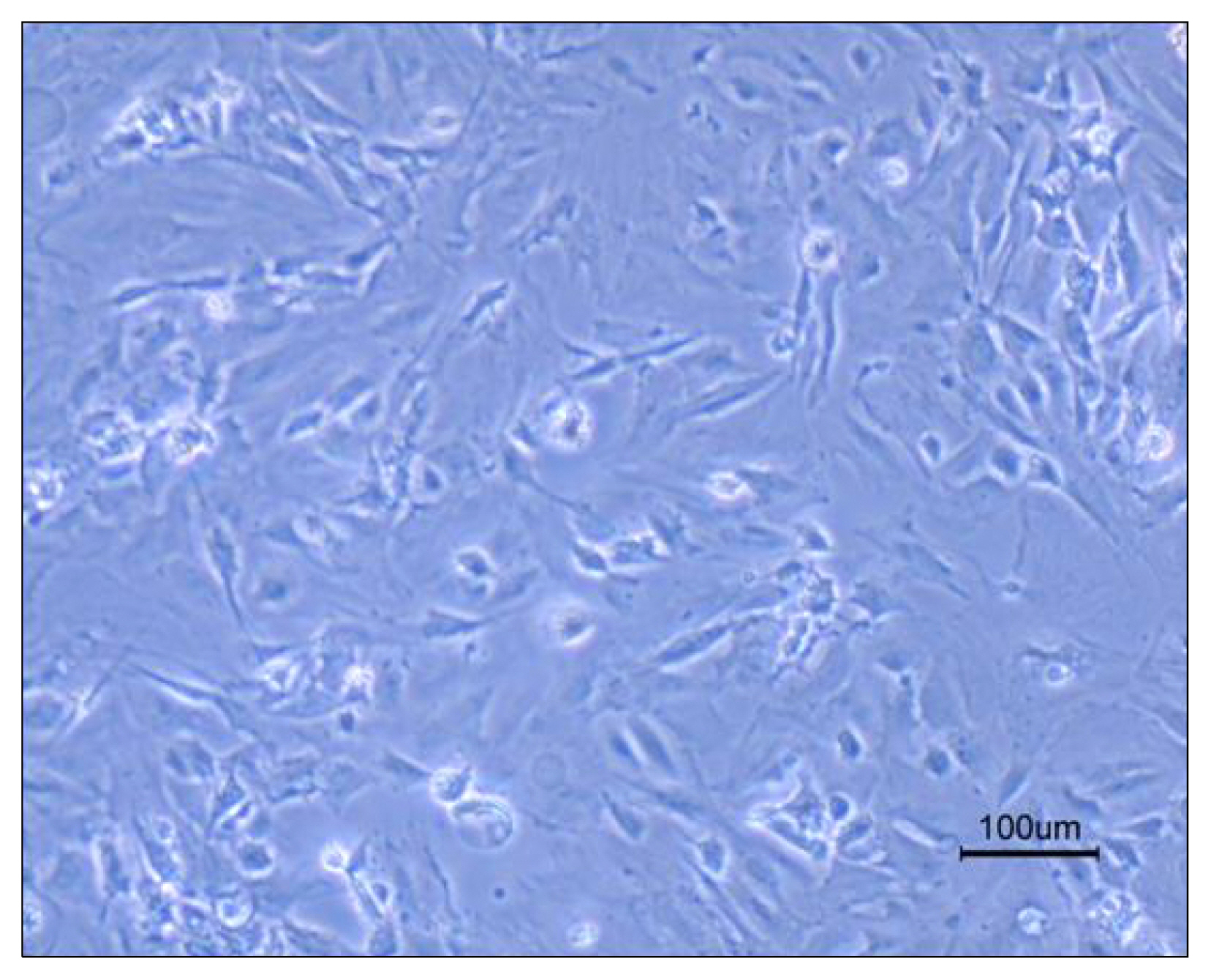

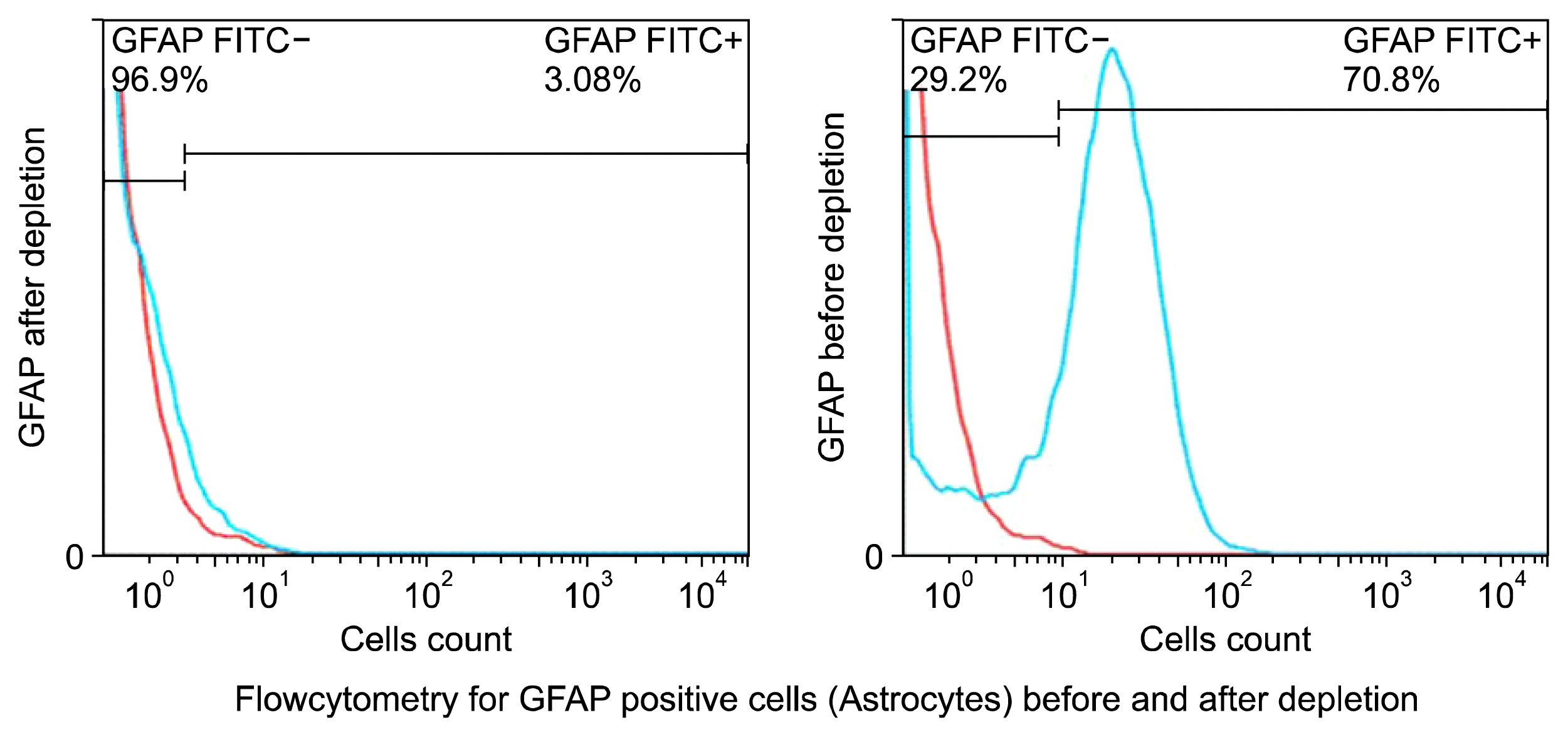

Nowadays, stroke leads to a significant part of the adult mortality and morbidity and also it could result in some neurological deficits in the patients' lives. Cell therapy has opened a new approach to treat the brain ischemia and reduce its terrible effects on the patients' lives. There are several articles which show that the cell therapy could be beneficial for treating brain stroke. In this study, we have planned to present a new cell therapy method for stroke by administration of Mesenchymal stem cells and differentiated neural stem cells without astrocytes. METHOD AND MATERIALS: The Mesenchymal stem cells were isolated from tibia and femur of a 250~300 g rat and they were cultured in DMEM/F12, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% Pen/Strep. Neural stem cells were isolated from 14 days rat embryo ganglion eminence and were cultured in NSA media containing Neurobasal, 2% B27, bFGF 10 ng/ml and EGF 20 ng/ml after 5 days they formed some neurospheres. The isolated neural stem cells were differentiated to neural lineages by adding 5% fetal bovine serum to their culture media. After 48 hours the astrocytes were depleted by using MACS kit.

RESULTS

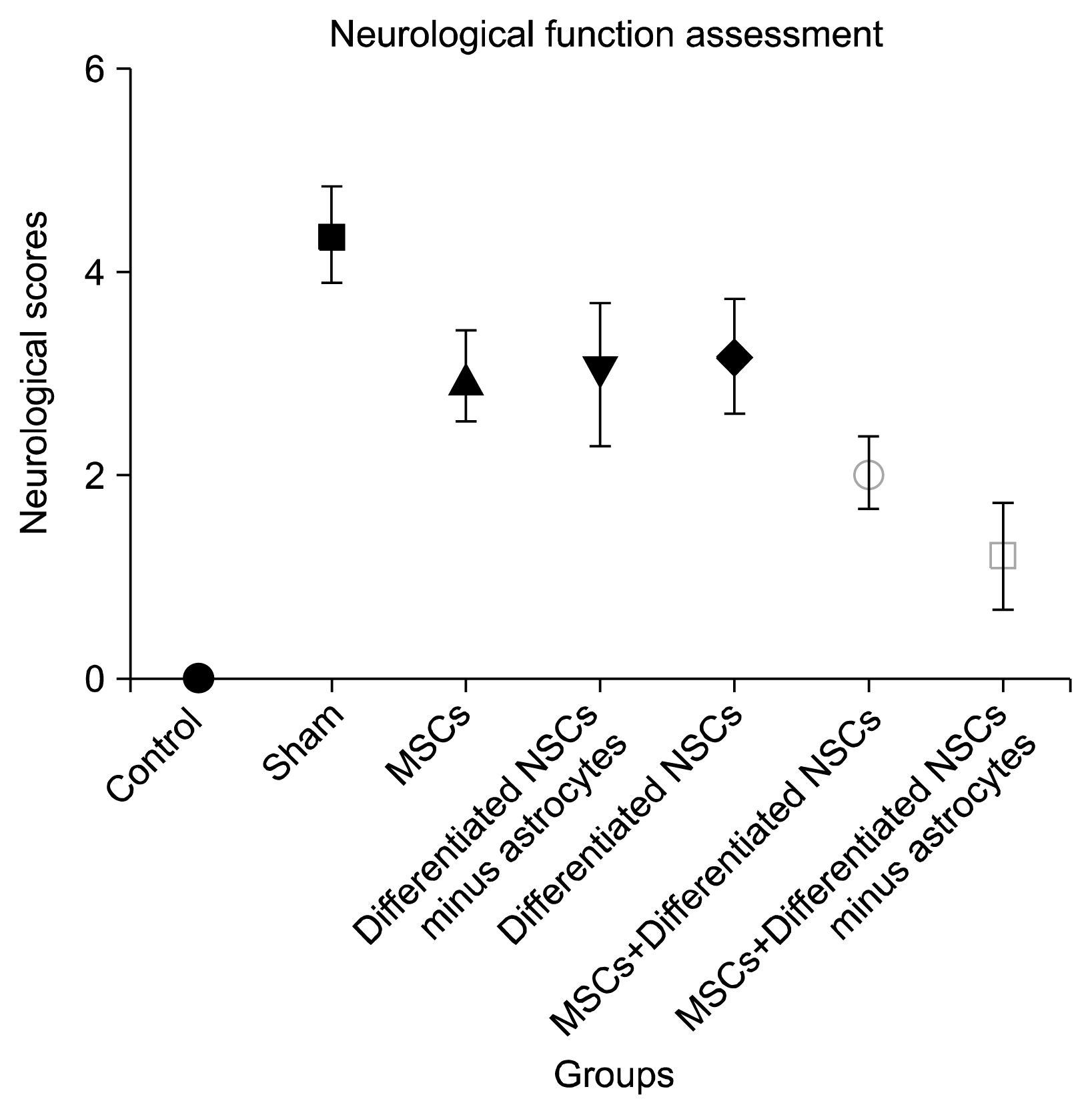

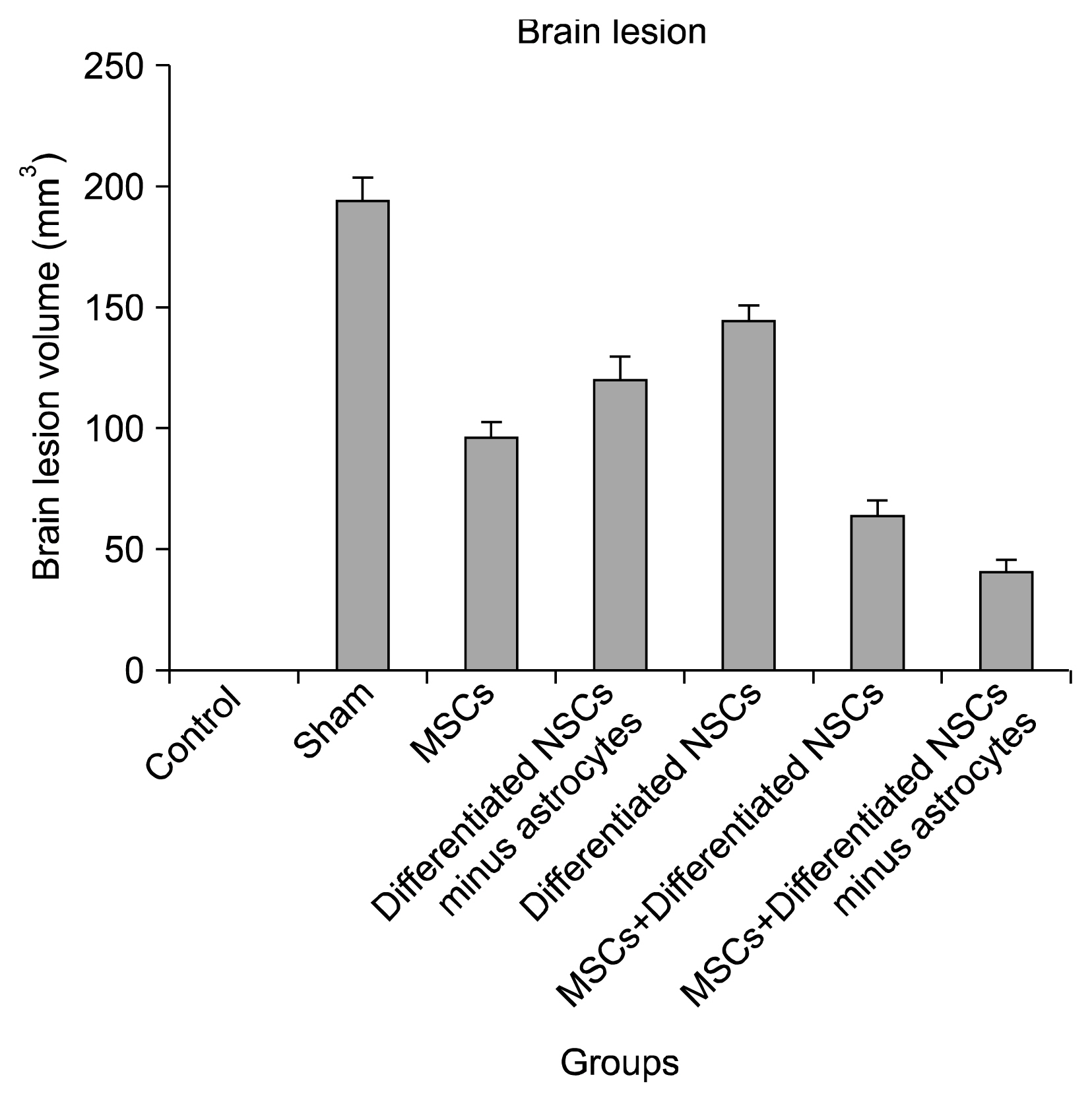

The group that received Mesenchymal stem cells systemically and differentiated neural stem cells without astrocytes had the best neurological outcomes and the least infarct volume and apoptosis. It could be understood that this cell therapy method might cause almost full recovery after brain stoke.

CONCLUSION

Using combination cell therapy with Mesenchymal stem cells and differentiated neural stem cells with removed astrocyte could provide a novel method for curing brain stroke.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Wu D. Neuroprotection in experimental stroke with targeted neurotrophins. NeuroRx. 2005; 2:120–128. DOI: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.120. PMID: 15717063. PMCID: 539332.

Article2. Broderick JP, William M. Feinberg Lecture: stroke therapy in the year 2025: burden, breakthroughs, and barriers to progress. Stroke. 2004; 35:205–211. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.0000106160.34316.19.3. Muir KW, Tyrrell P, Sattar N, Warburton E. Inflammation and ischaemic stroke. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007; 20:334–342. DOI: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32813ba151. PMID: 17495630.

Article4. Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999; 22:391–397. DOI: 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01401-0. PMID: 10441299.

Article5. Zhu Y, Yang GY, Ahlemeyer B, Pang L, Che XM, Culmsee C, Klumpp S, Krieglstein J. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 increases bad phosphorylation and protects neurons against damage. J Neurosci. 2002; 22:3898–3909. PMID: 12019309.

Article6. Spera PA, Ellison JA, Feuerstein GZ, Barone FC. IL-10 reduces rat brain injury following focal stroke. Neurosci Lett. 1998; 251:189–192. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00537-0. PMID: 9726375.

Article7. Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Hofer M. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med. 2009; 7:97. DOI: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-97. PMID: 19919699. PMCID: 2780998.

Article8. Swanson RA, Ying W, Kauppinen TM. Astrocyte influences on ischemic neuronal death. Curr Mol Med. 2004; 4:193–205. DOI: 10.2174/1566524043479185. PMID: 15032713.

Article9. Ginsberg MD. Cerebrovascular disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Blackwell Science, Bogousslavsky J. Malden, UK: Blackwell Science;1998. p. 193–204.10. Furlan AJ, Katzan IL, Caplan LR. Thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2003; 5:171–180. DOI: 10.1007/s11936-003-0001-4. PMID: 12777195.

Article11. Hirouchi M, Ukai Y. Current state on development of neuroprotective agents for cerebral ischemia. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2002; 120:107–113. DOI: 10.1254/fpj.120.107. PMID: 12187623.

Article12. Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, Pell CL, Johnstone BH, Considine RV, March KL. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004; 109:1292–1298. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1. PMID: 14993122.

Article13. Chang DJ, Oh SH, Lee N, Choi C, Jeon I, Kim HS, Shin DA, Lee SE, Kim D, Song J. Contralaterally transplanted human embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor cells (ENStem-A) migrate and improve brain functions in stroke-damaged rats. Exp Mol Med. 2013; 45:e53. DOI: 10.1038/emm.2013.93. PMID: 24232252. PMCID: 3849578.

Article14. Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Liu B, Zhang SX, Wu Y, Yu XD, Mao N. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005; 105:4120–4126. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. PMID: 15692068.

Article15. Koizumi J, Yoshida Y, Nakazawa T, Ooneda G. Experimental studies of ischemic brain edema: 1. A new experimental model of cerebral embolism in rats in which recirculation can be introduced in the ischemic area. Jpn J Stroke. 1986; 8:1–8. DOI: 10.3995/jstroke.8.1.16. Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989; 20:84–91. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.20.1.84. PMID: 2643202.

Article17. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, Grisanti S, Gianni AM. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002; 99:3838–3843. DOI: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3838. PMID: 11986244.

Article18. Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, Scott D, Laylor R, Simpson E, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003; 101:3722–3729. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104.

Article19. Ivanova-Todorova E, Bochev I, Mourdjeva M, Dimitrov R, Bukarev D, Kyurkchiev S, Tivchev P, Altunkova I, Kyurkchiev DS. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells are more potent suppressors of dendritic cells differentiation compared to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol Lett. 2009; 126:37–42. DOI: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.07.010. PMID: 19647021.

Article20. DelaRosa O, Dalemans W, Lombardo E. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutic agents of inflammatory and auto-immune diseases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012; 23:978–983. DOI: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.05.005. PMID: 22682584.

Article21. Ma S, Xie N, Li W, Yuan B, Shi Y, Wang Y. Immunobiology of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014; 21:216–225. DOI: 10.1038/cdd.2013.158. PMCID: 3890955.

Article22. Shi Y, Hu G, Su J, Li W, Chen Q, Shou P, Xu C, Chen X, Huang Y, Zhu Z, Huang X, Han X, Xie N, Ren G. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Res. 2010; 20:510–518. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2010.44. PMID: 20368733.

Article23. Cheng Q, Zhang Z, Zhang S, Yang H, Zhang X, Pan J, Weng L, Sha D, Zhu M, Hu X, Xu Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic brain injury in mouse by regulating peripheral immunoinflammation. Brain Res. 2015; 1594:293–304. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.065.

Article24. Calió ML, Marinho DS, Ko GM, Ribeiro RR, Carbonel AF, Oyama LM, Ormanji M, Guirao TP, Calió PL, Reis LA, Simões Mde J, Lisbôa-Nascimento T, Ferreira AT, Bertoncini CR. Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells decreases oxidative stress, apoptosis, and hippocampal damage in brain of a spontaneous stroke model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014; 70:141–154. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.024. PMID: 24525001.

Article25. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998; 4:1313–1317. DOI: 10.1038/3305. PMID: 9809557.

Article26. Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, Holtås S, van Roon-Mom WM, Björk-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, Frisén J, Dragunow M, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science. 2007; 315:1243–1249. DOI: 10.1126/science.1136281. PMID: 17303719.

Article27. Kornblum HI, Geschwind DH. Molecular markers in CNS stem cell research: hitting a moving target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001; 2:843–846. DOI: 10.1038/35097597. PMID: 11715062.

Article28. Bull ND, Bartlett PF. The adult mouse hippocampal progenitor is neurogenic but not a stem cell. J Neurosci. 2005; 25:10815–10821. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3249-05.2005. PMID: 16306394.

Article29. Taupin P. The therapeutic potential of adult neural stem cells. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2006; 8:225–231. PMID: 16774042.30. Batrakova EV, Gendelman HE, Kabanov AV. Cell-mediated drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011; 8:415–433. DOI: 10.1517/17425247.2011.559457. PMID: 21348773. PMCID: 3062753.

Article31. Ding S, Wang T, Cui W, Haydon PG. Photothrombosis ischemia stimulates a sustained astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in vivo. Glia. 2009; 57:767–776. DOI: 10.1002/glia.20804. PMCID: 2697167.

Article32. Li H, Zhang N, Sun G, Ding S. Inhibition of the group I mGluRs reduces acute brain damage and improves long-term histological outcomes after photothrombosis-induced ischaemia. ASN Neuro. 2013; 5:195–207. DOI: 10.1042/AN20130002. PMID: 23772679. PMCID: 3786425.

Article33. Panickar KS, Norenberg MD. Astrocytes in cerebral ischemic injury: morphological and general considerations. Glia. 2005; 50:287–298. DOI: 10.1002/glia.20181. PMID: 15846806.

Article34. Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, Barres BA. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J Neurosci. 2012; 32:6391–6410. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. PMID: 22553043. PMCID: 3480225.

Article35. Haupt C, Witte OW, Frahm C. Up-regulation of Connexin43 in the glial scar following photothrombotic ischemic injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007; 35:89–99. DOI: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.02.005. PMID: 17350281.

Article36. Hayakawa K, Nakano T, Irie K, Higuchi S, Fujioka M, Orito K, Iwasaki K, Jin G, Lo EH, Mishima K, Fujiwara M. Inhibition of reactive astrocytes with fluorocitrate retards neurovascular remodeling and recovery after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010; 30:871–882. DOI: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.257.

Article37. Barreto GE, Sun X, Xu L, Giffard RG. Astrocyte proliferation following stroke in the mouse depends on distance from the infarct. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e27881. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027881. PMID: 22132159. PMCID: 3221692.

Article38. Bao Y, Qin L, Kim E, Bhosle S, Guo H, Febbraio M, Haskew-Layton RE, Ratan R, Cho S. CD36 is involved in astrocyte activation and astroglial scar formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012; 32:1567–1577. DOI: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.52. PMID: 22510603. PMCID: 3421096.

Article39. Shimada IS, Borders A, Aronshtam A, Spees JL. Proliferating reactive astrocytes are regulated by Notch-1 in the peri-infarct area after stroke. Stroke. 2011; 42:3231–3237. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.623280. PMID: 21836083. PMCID: 4469355.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Combination Cell Therapy with Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Stem Cells for Brain Stroke in Rats

- Animal Models of Stroke

- Current Status and Therapeutic Perspectives for the Stem Cells Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

- Establishing Chronic Stroke Rat Models by MCA Occlusion Using Intraluminal Filament

- Clinical Trials of Adult Stem Cell Therapy in Patients with Ischemic Stroke