Tuberc Respir Dis.

2011 May;70(5):405-415.

The Effect of Tissue Plasminogen Activator on TGF-beta1 Pre-Treated Human Mesothelial Cell Line

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea. mjnamd@hanmail.net

- 3Myunggok Research Institute of Medical Science, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea.

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

In an effort to find alternative therapeutic agents to prevent excessive fibrosis as a sequela to complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema, we examined the effect of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) as a fibrinolytic agent combined with talc or transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 in a human pleural mesothelial cell line, MeT-5A.

METHODS

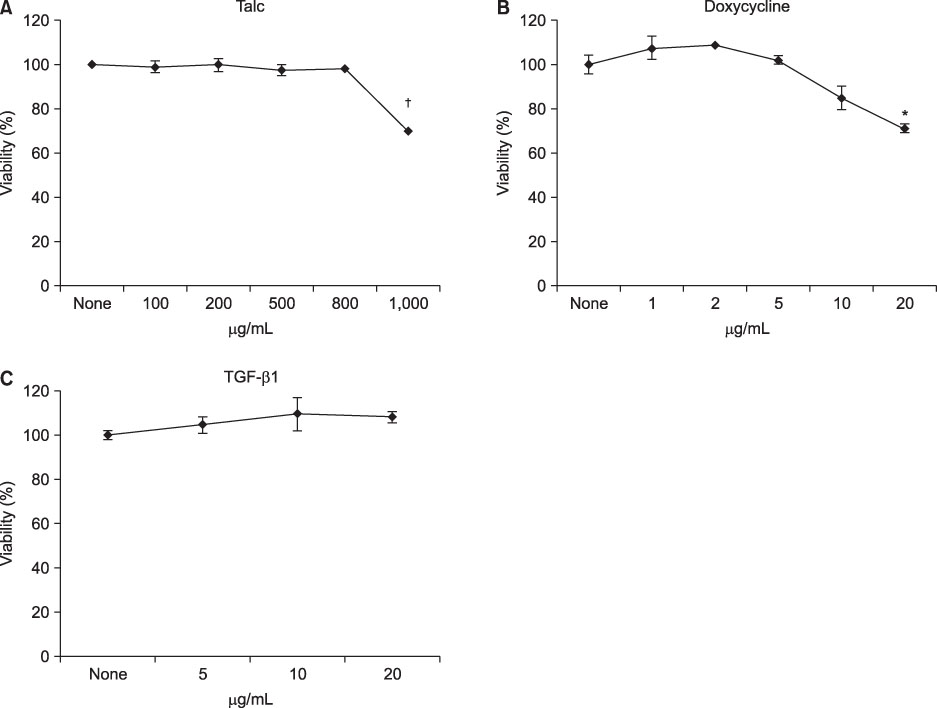

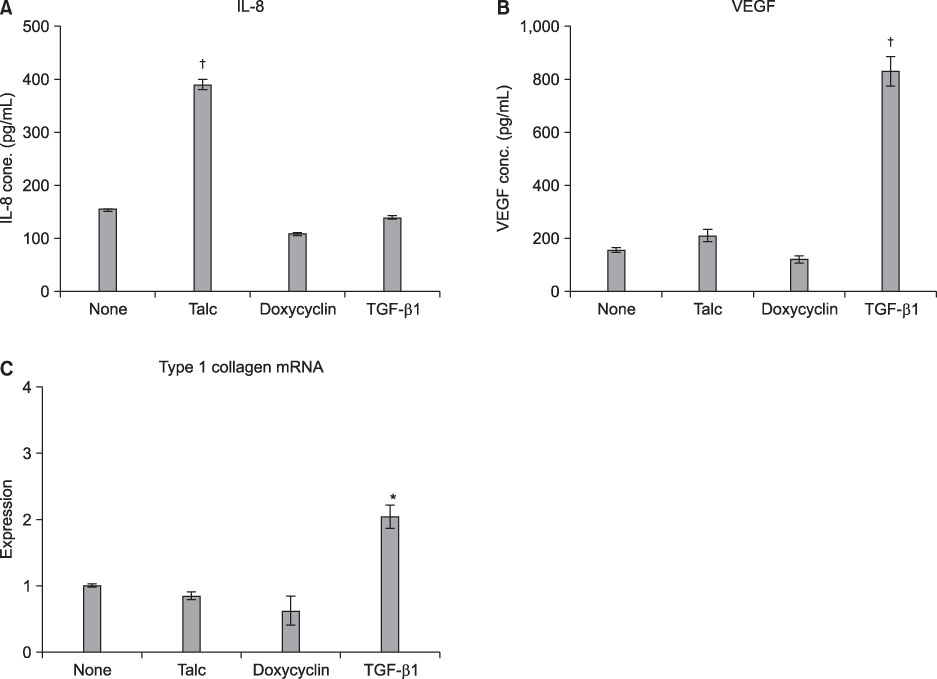

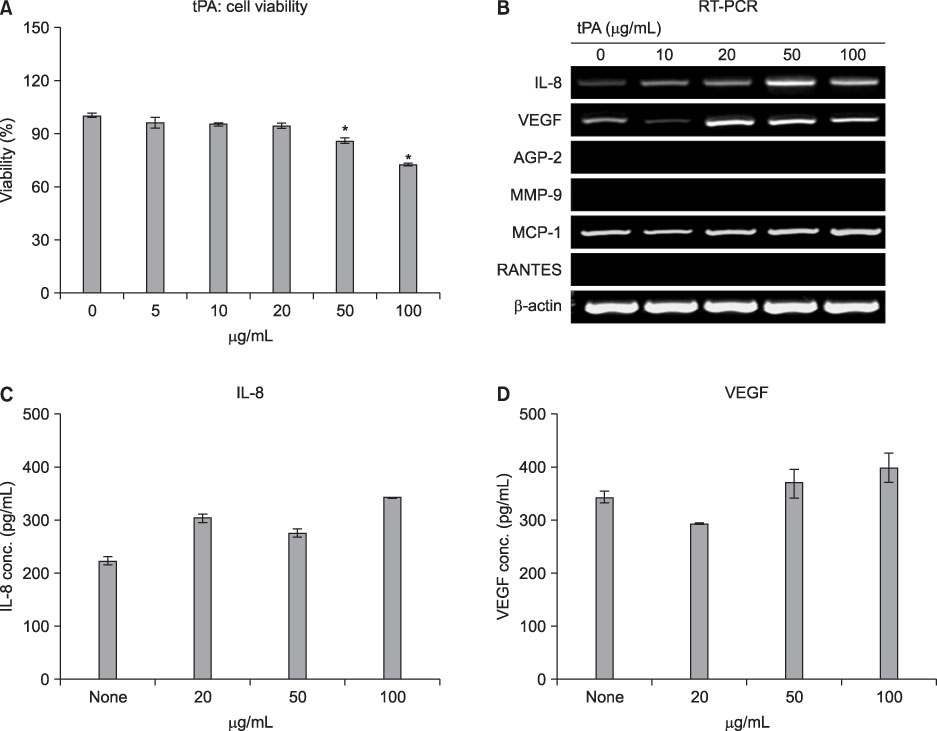

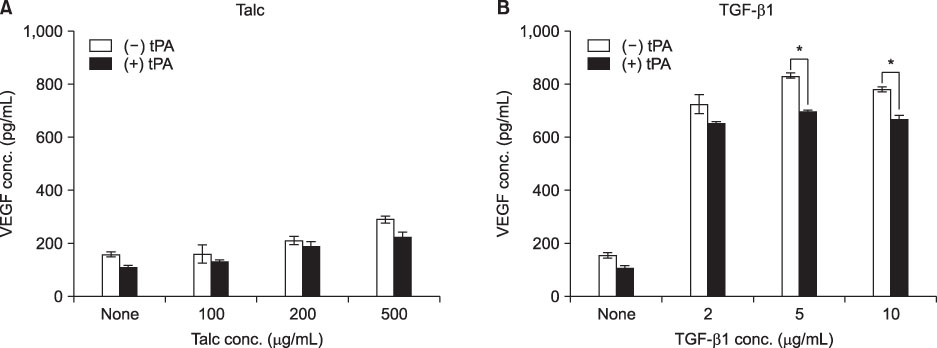

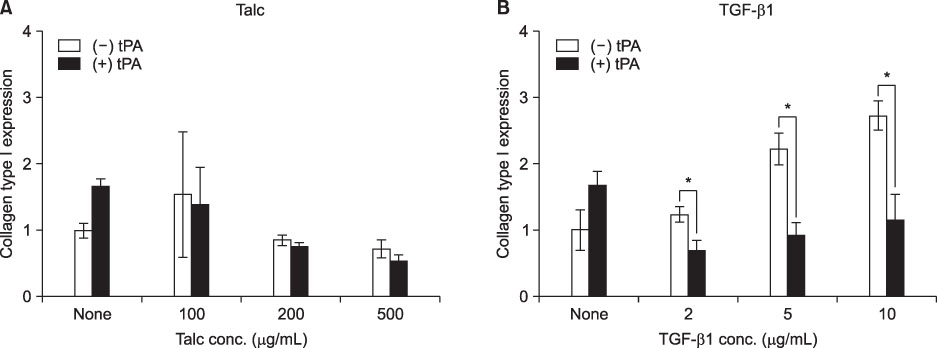

MeT-5A cells were stimulated with various doses of talc, doxycycline or TGF-beta1 for 24 h and then were treated with tPA for an additional 24 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. The production of interleukin (IL)-8 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Real-time PCR was carried out for measurement of type I collagen mRNA.

RESULTS

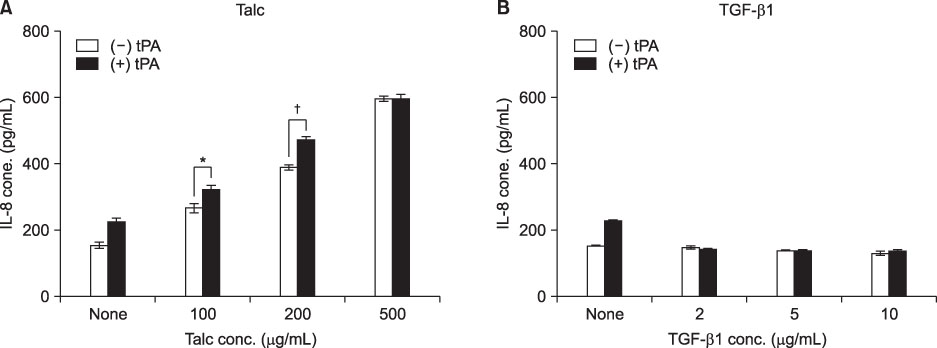

MeT-5A cells treated with talc showed a dose-dependent increase in production of IL-8. Talc also increased production of type I collagen mRNA at low doses, but talc did not influence the induction of VEGF. Addition of tPA to talc-stimulated cells showed further increases in the production of IL-8, but tPA did not influence the production of VEGF or type I collagen mRNA. TGF-beta1 increased the production of both VEGF and collagen type I mRNA, both of which were effectively inhibited by additional tPA treatment in MeT-5A cells.

CONCLUSION

TGF-beta1 is a potent inducer of collagen synthesis without induction of IL-8 in MeT-5A cells. Addition of tPA after TGF-beta1 stimulation inhibited further fibrosis by direct inhibition of collagen mRNA synthesis as well as by inhibition of VEGF production.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Cell Line

Cell Survival

Collagen

Collagen Type I

Doxycycline

Empyema

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Epithelium

Fibrosis

Humans

Interleukin-8

Interleukins

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA, Messenger

Talc

Tissue Plasminogen Activator

Transforming Growth Factor beta1

Transforming Growth Factors

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A

Collagen

Collagen Type I

Doxycycline

Interleukin-8

Interleukins

RNA, Messenger

Talc

Tissue Plasminogen Activator

Transforming Growth Factor beta1

Transforming Growth Factors

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A

Figure

Reference

-

1. Leard LE, Broaddus VC. Mesothelial cell proliferation and apoptosis. Respirology. 2004. 9:292–299.2. Iakhiaev AV, Nalian A, Koenig K, Idell S. Thrombin-thrombomodulin inhibits prourokinase-mediated pleural mesothelial cell-dependent fibrinolysis. Thromb Res. 2007. 120:715–725.3. Lee YC, Knight DA, Lane KB, Cheng DS, Koay MA, Teixeira LR, et al. Activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in mesothelial cells induces pleural inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005. 288:L734–L740.4. Diacon AH, Theron J, Schuurmans MM, Van de Wal BW, Bolliger CT. Intrapleural streptokinase for empyema and complicated parapneumonic effusions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004. 170:49–53.5. Misthos P, Sepsas E, Konstantinou M, Athanassiadi K, Skottis I, Lioulias A. Early use of intrapleural fibrinolytics in the management of postpneumonic empyema. A prospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005. 28:599–603.6. Maskell NA, Davies CW, Nunn AJ, Hedley EL, Gleeson FV, Miller R, et al. UK Controlled trial of intrapleural streptokinase for pleural infection. N Engl J Med. 2005. 352:865–874.7. Niedbala MJ, Picarella MS. Tumor necrosis factor induction of endothelial cell urokinase-type plasminogen activator mediated proteolysis of extracellular matrix and its antagonism by gamma-interferon. Blood. 1992. 79:678–687.8. Lee SR, Guo SZ, Scannevin RH, Magliaro BC, Rhodes KJ, Wang X, et al. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase, cytokines and chemokines in rat cortical astrocytes exposed to plasminogen activators. Neurosci Lett. 2007. 417:1–5.9. Ray TL, Berkenbosch JW, Russo P, Tobias JD. Tissue plasminogen activator as an adjuvant therapy for pleural empyema in pediatric patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2004. 19:44–50.10. Bishop NB, Pon S, Ushay HM, Greenwald BM. Alteplase in the treatment of complicated parapneumonic effusion: a case report. Pediatrics. 2003. 111:E188–E190.11. Walker CA, Shirk MB, Tschampel MM, Visconti JA. Intrapleural alteplase in a patient with complicated pleural effusion. Ann Pharmacother. 2003. 37:376–379.12. Weinstein M, Restrepo R, Chait PG, Connolly B, Temple M, Macarthur C. Effectiveness and safety of tissue plasminogen activator in the management of complicated parapneumonic effusions. Pediatrics. 2004. 113:e182–e185.13. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983. 65:55–63.14. Mutsaers SE, Prele CM, Brody AR, Idell S. Pathogenesis of pleural fibrosis. Respirology. 2004. 9:428–440.15. Kennedy L, Harley RA, Sahn SA, Strange C. Talc slurry pleurodesis. Pleural fluid and histologic analysis. Chest. 1995. 107:1707–1712.16. Light RW. Talc for pleurodesis? Chest. 2002. 122:1506–1508.17. Light RW, Cheng DS, Lee YC, Rogers J, Davidson J, Lane KB. A single intrapleural injection of transforming growth factor-beta(2) produces an excellent pleurodesis in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 162:98–104.18. Lee YC, Lane KB, Zoia O, Thompson PJ, Light RW, Blackwell TS. Transforming growth factor-beta induces collagen synthesis without inducing IL-8 production in mesothelial cells. Eur Respir J. 2003. 22:197–202.19. Kalomenidis I, Guo Y, Lane KB, Hawthorne M, Light RW. Transforming growth factor-beta3 induces pleurodesis in rabbits and collagen production of human mesothelial cells. Chest. 2005. 127:1335–1340.20. Gary Lee YC, Melkerneker D, Thompson PJ, Light RW, Lane KB. Transforming growth factor beta induces vascular endothelial growth factor elaboration from pleural mesothelial cells in vivo and in vitro. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. 165:88–94.21. Sasse SA, Jadus MR, Kukes GD. Pleural fluid transforming growth factor-beta1 correlates with pleural fibrosis in experimental empyema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 168:700–705.22. Samarakoon R, Higgins SP, Higgins CE, Higgins PJ. TGF-beta1-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells requires pp60(c-src)/EGFR(Y845) and Rho/ROCK signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008. 44:527–538.23. Grove CS, Lee YC. Vascular endothelial growth factor: the key mediator in pleural effusion formation. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002. 8:294–301.24. Ferrara N. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med. 1999. 77:527–543.25. Boussat S, Eddahibi S, Coste A, Fataccioli V, Gouge M, Housset B, et al. Expression and regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000. 279:L371–L378.26. Koochekpour S, Merzak A, Pilkington GJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor production is stimulated by gangliosides and TGF-beta isoforms in human glioma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett. 1996. 102:209–215.27. Donovan D, Harmey JH, Toomey D, Osborne DH, Redmond HP, Bouchier-Hayes DJ. TGF beta-1 regulation of VEGF production by breast cancer cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997. 4:621–627.28. Thickett DR, Armstrong L, Millar AB. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in inflammatory and malignant pleural effusions. Thorax. 1999. 54:707–710.29. Cheng D, Rodriguez RM, Perkett EA, Rogers J, Bienvenu G, Lappalainen U, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in pleural fluid. Chest. 1999. 116:760–765.30. Gervais DA, Levis DA, Hahn PF, Uppot RN, Arellano RS, Mueller PR. Adjunctive intrapleural tissue plasminogen activator administered via chest tubes placed with imaging guidance: effectiveness and risk for hemorrhage. Radiology. 2008. 246:956–963.31. Levinson GM, Pennington DW. Intrapleural fibrinolytics combined with image-guided chest tube drainage for pleural infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007. 82:407–413.32. Skeete DA, Rutherford EJ, Schlidt SA, Abrams JE, Parker LA, Rich PB. Intrapleural tissue plasminogen activator for complicated pleural effusions. J Trauma. 2004. 57:1178–1183.33. Thommi G, Nair CK, Aronow WS, Shehan C, Meyers P, McLeay M. Efficacy and safety of intrapleural instillation of alteplase in the management of complicated pleural effusion or empyema. Am J Ther. 2007. 14:341–345.34. Zuckerman DA, Reed MF, Howington JA, Moulton JS. Efficacy of intrapleural tissue-type plasminogen activator in the treatment of loculated parapneumonic effusions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009. 20:1066–1069.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of immune-mediated vascular injury on the coagulation- regulatory mechanism of the human endothelial cells; changes of tissue-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor- 1 and von Willebrand factor

- The Inhibitory Effect of siRNAs on The High Glucose-Induced Overexpression of TGF-beta1 in Mesangial Cells

- Transforming Growth Factor-beta1(TGF-beta1) Synthesis of Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cell

- Intravitreal Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Gas Injection in Submacular Hemorrhage

- The Effect of TGF-beta1 on Cellular Activity of Periodontal Ligament Cells activated by PDGF-BB