Korean J Pain.

2024 Jul;37(3):218-232. 10.3344/kjp.23355.

Assessment of antinociceptive property of Cynara scolymus L. and possible mechanism of action in the formalin and writhing models of nociception in mice

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Basic Sciences and Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran

- KMID: 2557726

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.23355

Abstract

- Background

Cynara scolymus has bioactive constituents and has been used for therapeutic actions. The present study was undertaken to investigate the mechanisms underlying pain-relieving effects of the hydroethanolic extract of C. scolymus (HECS).

Methods

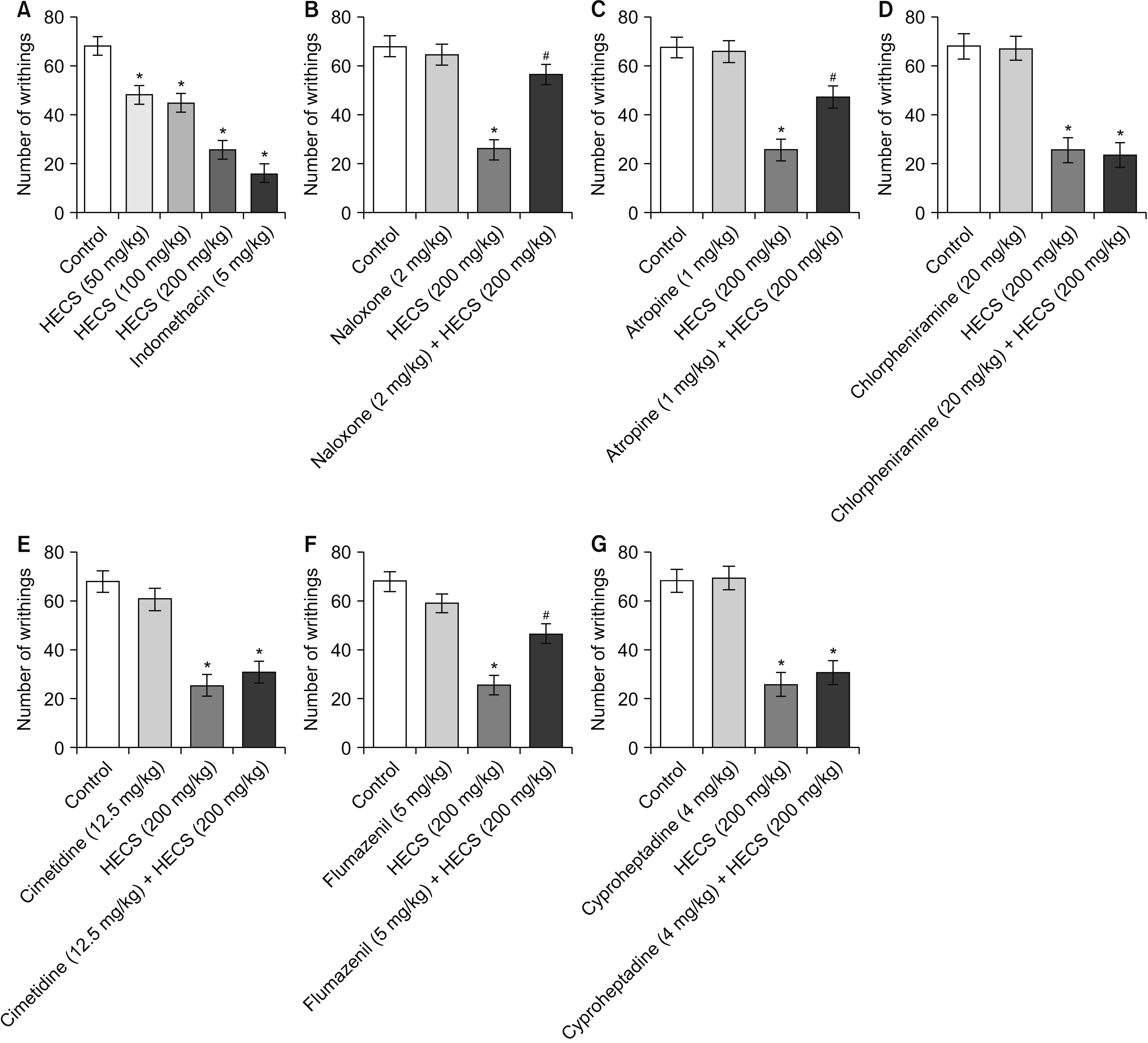

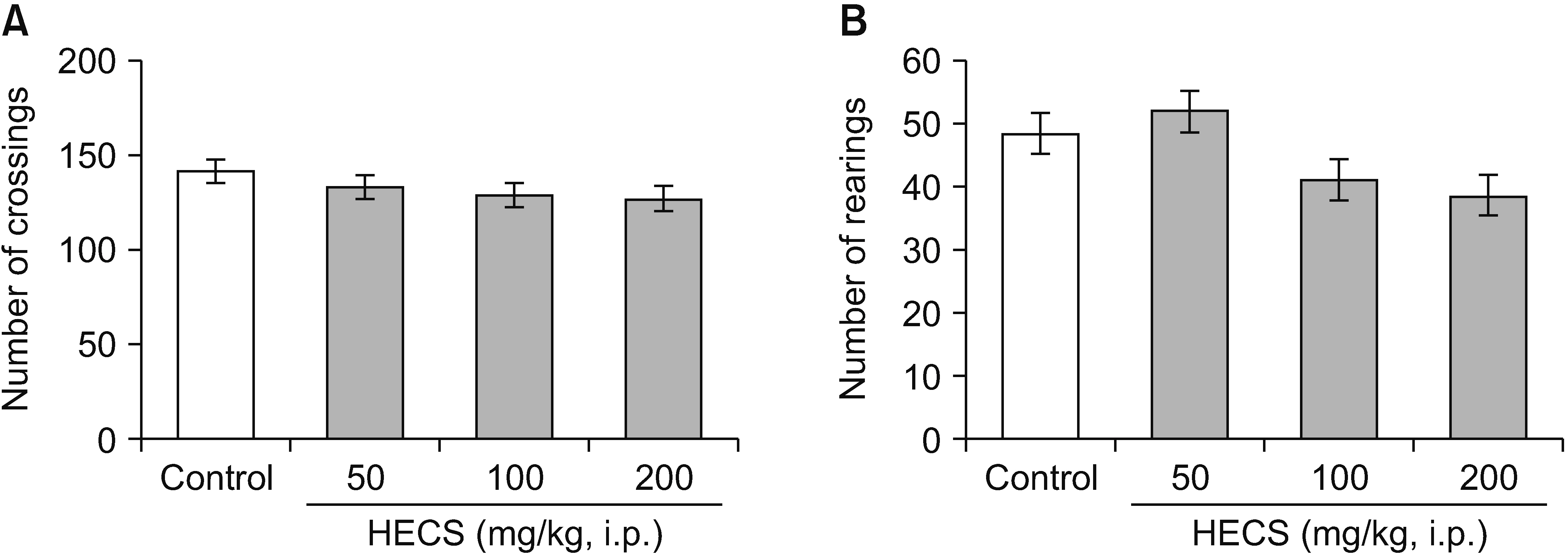

The antinociceptive activity of HECS was assessed through formalin and acetic acid-induced writhing tests at doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally. Additionally, naloxone (non-selective opioid receptors antagonist, 2 mg/kg), atropine (non-selective muscarinic receptors antagonist, 1 mg/kg), chlorpheniramine (histamine H1 -receptor antagonist, 20 mg/kg), cimetidine (histamine H2 -receptor antagonist, 12.5 mg/kg), flumazenil (GABAA /BDZ receptor antagonist, 5 mg/kg) and cyproheptadine (serotonin receptor antagonist, 4 mg/kg) were used to determine the systems implicated in HECS-induced analgesia. Impact of HECS on locomotor activity was executed by open-field test. Determination of total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) was done. Evaluation of antioxidant activity was conducted employing 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay.

Results

HECS (50, 100 and 200 mg/kg) significantly indicated dose dependent antinociceptive activity against pain-related behavior induced by formalin and acetic acid (P < 0.001). Pretreatment with naloxone, atropine and flumazenil significantly reversed HECS-induced analgesia. Antinociceptive effect of HECS remained unaffected by chlorpheniramine, cimetidine and cyproheptadine. Locomotor activity was not affected by HECS. TPC and TFC of HECS were 59.49 ± 5.57 mgGAE/g dry extract and 93.39 ± 17.16 mgRE/g dry extract, respectively. DPPH free radical scavenging activity (IC 50 ) of HECS was 161.32 ± 0.03 µg/mL.

Conclusions

HECS possesses antinociceptive activity which is mediated via opioidergic, cholinergic and GABAergic pathways.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. eekeesoon DP Sr, Mahomoodally MF. 2014; Ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants and animals used in the treatment and management of pain in Mauritius. J Ethnopharmacol. 157:181–200. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030. PMID: 25261690.

Article2. Olorukooba AB, Odoma S. 2019; Elucidation of the possible mechanism of analgesic action of methanol stem bark extract of Uapaca togoensis pax in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 245:112156. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112156. PMID: 31415847.

Article3. Mohammadifard F, Alimohammadi S. 2018; Chemical composition and role of opioidergic system in antinociceptive effect of Ziziphora Clinopodioides essential oil. Basic Clin Neurosci. 9:357–66. DOI: 10.32598/bcn.9.5.357. PMID: 30719250. PMCID: PMC6360493.4. Koohsari S, Sheikholeslami MA, Parvardeh S, Ghafghazi S, Samadi S, Poul YK, et al. 2020; Antinociceptive and antineuropathic effects of cuminaldehyde, the major constituent of Cuminum cyminum seeds: possible mechanisms of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 255:112786. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112786. PMID: 32222574.5. Ben Salem M, Affes H, Ksouda K, Dhouibi R, Sahnoun Z, Hammami S, et al. 2015; Pharmacological studies of artichoke leaf extract and their health benefits. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 70:441–53. DOI: 10.1007/s11130-015-0503-8. PMID: 26310198.

Article6. Mejri F, Baati T, Martins A, Selmi S, Luisa Serralheiro M, Falé PL, et al. 2020; Phytochemical analysis and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of biological activities of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) floral stems: towards the valorization of food by-products. Food Chem. 333:127506. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127506. PMID: 32679417.

Article7. Salekzamani S, Ebrahimi-Mameghani M, Rezazadeh K. 2019; The antioxidant activity of artichoke (Cynara scolymus): a systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Phytother Res. 33:55–71. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.6213. PMID: 30345589.

Article8. Ben Salem M, Ben Abdallah Kolsi R, Dhouibi R, Ksouda K, Charfi S, Yaich M, et al. 2017; Protective effects of Cynara scolymus leaves extract on metabolic disorders and oxidative stress in alloxan-diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 17:328. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-017-1835-8. PMID: 28629341. PMCID: PMC5477270.

Article9. Mocelin R, Marcon M, Santo GD, Zanatta L, Sachett A, Schönell AP, et al. 2016; Hypolipidemic and antiatherogenic effects of Cynara scolymus in cholesterol-fed rats. Rev Bras Farmacognosia. 26:233–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjp.2015.11.004.10. Ben Salem M, Affes H, Athmouni K, Ksouda K, Dhouibi R, Sahnoun Z, et al. 2017; Chemicals compositions, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of Cynara scolymus leaves extracts, and analysis of major bioactive polyphenols by HPLC. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:4951937. DOI: 10.1155/2017/4951937. PMID: 28539965. PMCID: PMC5429947.

Article11. Alahmoradi M, Alimohammadi S, Cheraghi H. 2019; Protective effect of Cynara scolymus L. on blood biochemical parameters and liver histopathological changes in phenylhydrazine-induced hemolytic anemia in rats. Pharm Biomed Res. 5:53–62. DOI: 10.18502/pbr.v5i4.2397.12. Allahmoradi M, Alimohammadi S, Cheraghi H. 2020; Amelioration of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes status in the serum and erythrocytes of phenylhydrazine-induced anemic male rats: the protective role of artichoke extract (Cynara scolymus L.). Iran J Vet Med. 14:315–28.13. Zimmermann M. 1983; Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 16:109–10. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. PMID: 6877845.

Article14. Kavaliers M, Hirst M. 1983; Daily rhythms of analgesia in mice: effects of age and photoperiod. Brain Res. 279:387–93. DOI: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90216-0. PMID: 6315182.

Article15. Montiel-Ruiz RM, González-Trujano ME, Déciga-Campos M. 2013; Synergistic interactions between the antinociceptive effect of Rhodiola rosea extract and B vitamins in the mouse formalin test. Phytomedicine. 20:1280–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.07.006. PMID: 23920277.

Article16. Zendehdel M, Torabi Z, Hassanpour S. 2015; Antinociceptive mechanisms of Bunium persicum essential oil in the mouse writhing test: role of opioidergic and histaminergic systems. Vet Med. 60:63–70. DOI: 10.17221/7988-VETMED.

Article17. Oliveira AS, Cercato LM, de Santana Souza MT, Melo AJO, Lima BDS, Duarte MC, et al. 2017; The ethanol extract of Leonurus sibiricus L. induces antioxidant, antinociceptive and topical anti-inflammatory effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 206:144–51. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.05.029. PMID: 28549861.

Article18. Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. 1999; The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 64:555–9. DOI: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2.

Article19. Blois MS. 1958; Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 181:1199–200. DOI: 10.1038/1811199a0.20. Khalil M, Khalifeh H, Baldini F, Salis A, Damonte G, Daher A, et al. 2019; Antisteatotic and antioxidant activities of Thymbra spicata L. extracts in hepatic and endothelial cells as in vitro models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Ethnopharmacol. 239:111919. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111919. PMID: 31029756.

Article21. Tamaddonfard E, Hamzeh-Gooshchi N. 2010; Effect of crocin on the morphine-induced antinociception in the formalin test in rats. Phytother Res. 24:410–3. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.2965. PMID: 19653196.

Article22. Dubuisson D, Dennis SG. 1977; The formalin test: a quantitative study of the analgesic effects of morphine, meperidine, and brain stem stimulation in rats and cats. Pain. 4:161–74. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. PMID: 564014.

Article23. Abbott FV, Bonder M. 1997; Options for management of acute pain in the rat. Vet Rec. 140:553–7. DOI: 10.1136/vr.140.21.553. PMID: 9185312.

Article24. Koster R, Anderson M, De Beer EJ. 1959; Acetic acid for analgesic screening. Fed Proc. 18:412–7.25. Hishe HZ, Ambech TA, Hiben MG, Fanta BS. 2018; Anti-nociceptive effect of methanol extract of leaves of Senna singueana in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 217:49–53. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.02.002. PMID: 29421592.

Article26. Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. 2018; General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 19:2164. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19082164. PMID: 30042373. PMCID: PMC6121522.

Article27. Hunskaar S, Hole K. 1987; The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 30:103–14. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. PMID: 3614974.

Article28. Ribeiro RA, Vale ML, Thomazzi SM, Paschoalato AB, Poole S, Ferreira SH, et al. 2000; Involvement of resident macrophages and mast cells in the writhing nociceptive response induced by zymosan and acetic acid in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 387:111–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00790-6. PMID: 10633169.

Article29. Karbab A, Mokhnache K, Ouhida S, Charef N, Djabi F, Arrar L, et al. 2020; Anti-inflammatory, analgesic activity, and toxicity of Pituranthos scoparius stem extract: an ethnopharmacological study in rat and mouse models. J Ethnopharmacol. 258:112936. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112936. PMID: 32376367.

Article30. Ferraz CR, Carvalho TT, Manchope MF, Artero NA, Rasquel-Oliveira FS, Fattori V, et al. 2020; Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in pain and inflammation: mechanisms of action, pre-clinical and clinical data, and pharmaceutical development. Molecules. 25:762. DOI: 10.3390/molecules25030762. PMID: 32050623. PMCID: PMC7037709.

Article31. Bagdas D, Ozboluk HY, Cinkilic N, Gurun MS. 2014; Antinociceptive effect of chlorogenic acid in rats with painful diabetic neuropathy. J Med Food. 17:730–2. DOI: 10.1089/jmf.2013.2966. PMID: 24611441.

Article32. dos Santos MD, Almeida MC, Lopes NP, de Souza GE. 2006; Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities of the natural polyphenol chlorogenic acid. Biol Pharm Bull. 29:2236–40. DOI: 10.1248/bpb.29.2236. PMID: 17077520.

Article33. Shan J, Fu J, Zhao Z, Kong X, Huang H, Luo L, et al. 2009; Chlorogenic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells through suppressing NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 9:1042–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.011. PMID: 19393773.34. Pinheiro MM, Boylan F, Fernandes PD. 2012; Antinociceptive effect of the Orbignya speciosa Mart. (Babassu) leaves: evidence for the involvement of apigenin. Life Sci. 91:293–300. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.06.013. PMID: 22749864.

Article35. Aziz N, Kim MY, Cho JY. 2018; Anti-inflammatory effects of luteolin: a review of in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies. J Ethnopharmacol. 225:342–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.019. PMID: 29801717.

Article36. Miño J, Acevedo C, Moscatelli V, Ferraro G, Hnatyszyn O. 2002; Antinociceptive effect of the aqueous extract of Balbisia calycina. J Ethnopharmacol. 79:179–82. DOI: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00372-5. PMID: 11801379.

Article37. Filho AW, Filho VC, Olinger L, de Souza MM. 2008; Quercetin: further investigation of its antinociceptive properties and mechanisms of action. Arch Pharm Res. 31:713–21. DOI: 10.1007/s12272-001-1217-2. PMID: 18563352.

Article38. Toker G, Küpeli E, Memisoğlu M, Yesilada E. 2004; Flavonoids with antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities from the leaves of Tilia argentea (silver linden). J Ethnopharmacol. 95:393–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.008. PMID: 15507365.

Article39. Yousofvand N, Moloodi B. 2023; An overview of the effect of medicinal herbs on pain. Phytother Res. 37:1057–81. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.7697. PMID: 36585701.40. Bodnar RJ. 2020; Endogenous opiates and behavior:. Peptides. 132:170348. DOI: 10.1016/j.peptides.2020.170348. PMID: 32574695.41. Eisenach JC. 1999; Muscarinic-mediated analgesia. Life Sci. 64:549–54. DOI: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00600-6. PMID: 10069522.

Article42. Naser PV, Kuner R. 2018; Molecular, cellular and circuit basis of cholinergic modulation of pain. Neuroscience. 387:135–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.08.049. PMID: 28890048. PMCID: PMC6150928.

Article43. Goudet C, Magnaghi V, Landry M, Nagy F, Gereau RW 4th, Pin JP. 2009; Metabotropic receptors for glutamate and GABA in pain. Brain Res Rev. 60:43–56. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.007. PMID: 19146876.

Article44. Mahdian Dehkordi F, Kaboutari J, Zendehdel M, Javdani M. 2019; The antinociceptive effect of artemisinin on the inflammatory pain and role of GABAergic and opioidergic systems. Korean J Pain. 32:160–7. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2019.32.3.160. PMID: 31257824. PMCID: PMC6615442.

Article45. Hara K, Haranishi Y, Kataoka K, Takahashi Y, Terada T, Nakamura M, et al. 2014; Chlorogenic acid administered intrathecally alleviates mechanical and cold hyperalgesia in a rat neuropathic pain model. Eur J Pharmacol. 723:459–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.046. PMID: 24184666.46. Obara I, Telezhkin V, Alrashdi I, Chazot PL. 2020; Histamine, histamine receptors, and neuropathic pain relief. Br J Pharmacol. 177:580–99. DOI: 10.1111/bph.14696. PMID: 31046146. PMCID: PMC7012972.

Article47. Li P, Zhuo M. 2001; Cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic inhibition of fast synaptic transmission in spinal lumbar dorsal horn of rat. Brain Res Bull. 54:639–47. DOI: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00470-1. PMID: 11403990.48. Martinello K, Sucapane A, Fucile S. 2022; 5-HT3 receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: Ca2+ entry and modulation of neurotransmitter release. Life (Basel). 12:1178. DOI: 10.3390/life12081178. PMID: 36013357. PMCID: PMC9409985.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antinociception Effect and Mechanisms of Campanula Punctata Extract in the Mouse

- Hop Extract Produces Antinociception by Acting on Opioid System in Mice

- Effect of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb Extract on the Antinociception and Mechanisms in Mouse

- Evaluation of the antinociceptive effects of a selection of triazine derivatives in mice

- Antinociceptive Effect of Intraperitoneally Administered 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide on Formalin Induced Nociception in Rats