Korean J Pain.

2022 Oct;35(4):440-446. 10.3344/kjp.2022.35.4.440.

Evaluation of the antinociceptive effects of a selection of triazine derivatives in mice

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

- 2Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

- KMID: 2533984

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2022.35.4.440

Abstract

- Background

The authors showed in a previous study that some novel triazine derivatives had an anti-inflammatory effect. The present study was designed to evaluate the antinociceptive effect of five out of nine compounds including two vanillintriazine (5c and 5d) and three phenylpyrazole-triazine (10a, 10b, 10e) derivatives which showed the best anti-inflammatory effect.

Methods

Male Swiss mice (25–30 g) were used. To assess the antinociceptive effect, acetic acid-writhing, formalin, and hot plate tests were used after intraperitoneal injection of each compound.

Results

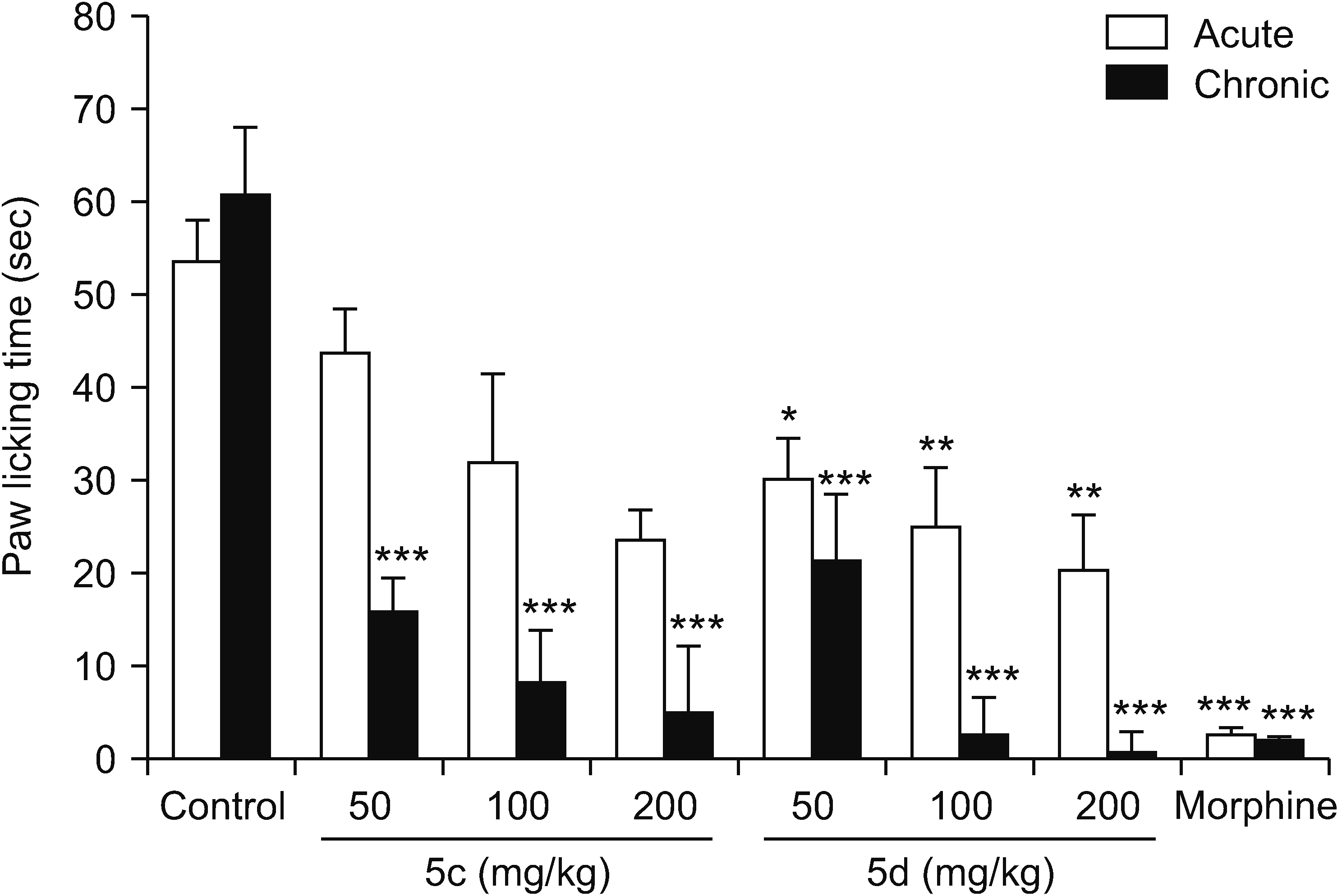

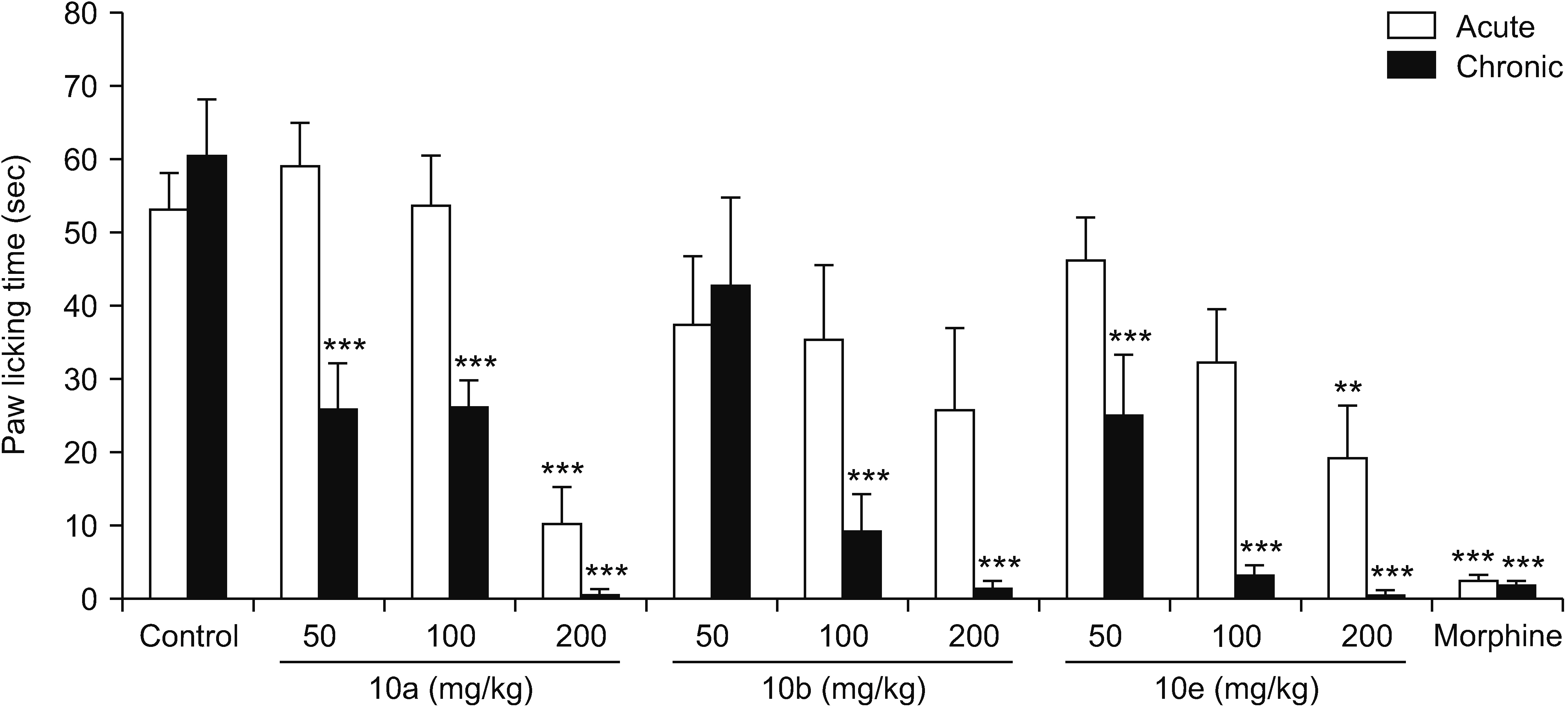

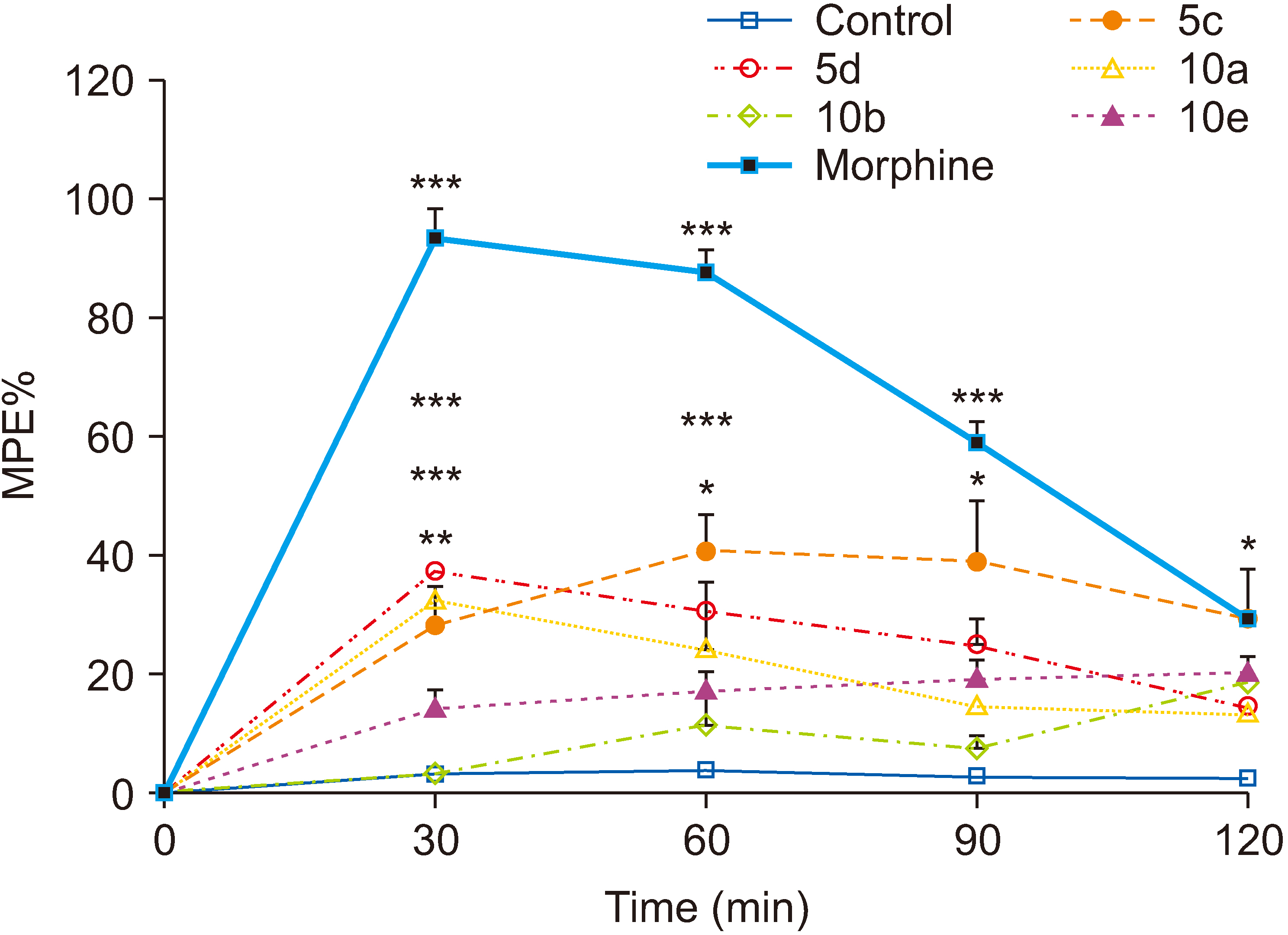

All compounds significantly (P < 0.001) reduced acetic acid-induced writhing at tested doses (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg). Also, the percent inhibition of writhing in the acetic acid test showed that at the maximum tested dose of these compounds (200 mg/kg), the order of potencies is as follows: 10b > 10a > 10e > 5d > 5c. In the formalin test, compounds 5d, 10a, and 10e showed an antinociceptive effect in the acute phase and all compounds were effective in the chronic phase. In the hot plate test, compounds 5c, 5d, and 10a demonstrated an antinociceptive effect.

Conclusions

The results clearly showed that both vanillin-triazine and phenylpyrazole-triazine derivatives had an antinociceptive effect. Also, some compounds which showed activity in the early phase of formalin test as well as in the hot plate test could control acute pain in addition to chronic or inflammatory pain.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Evaluation of the antinociceptive activities of natural propolis extract derived from stingless bee

Trigona thoracica in mice

Nurul Alina Muhamad Suhaini, Mohd Faeiz Pauzi, Siti Norazlina Juhari, Noor Azlina Abu Bakar, Jee Youn Moon

Korean J Pain. 2024;37(2):141-150. doi: 10.3344/kjp.23318.

Reference

-

1. Wongrakpanich S, Wongrakpanich A, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. 2018; A comprehensive review of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the elderly. Aging Dis. 9:143–50. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2017.0306. PMID: 29392089. PMCID: PMC5772852. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=85043705728&origin=inward.

Article2. Clària J. 2003; Cyclooxygenase-2 biology. Curr Pharm Des. 9:2177–90. DOI: 10.2174/1381612033454054. PMID: 14529398. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0141538107&origin=inward.

Article3. Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. 2000; Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 69:145–82. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. PMID: 10966456. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0033791318&origin=inward.

Article4. Gupta S, Crofford LJ. 2001; An update on specific COX-2 inhibitors: the COXIBs. Bull Rheum Dis. 50:1–4. PMID: 12092091. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0034955602&origin=inward.5. Vishwakarma RK, Negi DS. 2020; The development of COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 11:3544–55. PMID: 0bb85cf3f39a47d3b9ee87328f9b1da6. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0034955602&origin=inward.6. Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, et al. 2000; Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 284:1247–55. DOI: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247. PMID: 10979111. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0034644396&origin=inward.

Article7. Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, et al. 2000; Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 343:1520–8. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. PMID: 11087881. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0034707105&origin=inward.

Article8. Laine L. 2003; Gastrointestinal effects of NSAIDs and coxibs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 25(2 Suppl):S32–40. DOI: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00629-2. PMID: 12604155. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0037320997&origin=inward.

Article9. Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. 2006; Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 332:1302–8. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. PMID: 16740558. PMCID: PMC1473048. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=33744976771&origin=inward.

Article10. Arora M, Choudhary S, Singh PK, Sapra B, Silakari O. 2020; Structural investigation on the selective COX-2 inhibitors mediated cardiotoxicity: a review. Life Sci. 251:117631. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117631. PMID: 32251635. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=85082941157&origin=inward.

Article11. Salvo F, Fourrier-Réglat A, Bazin F, Robinson P, Riera-Guardia N, Haag M, et al. 2011; Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of NSAIDs: a systematic review of meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 89:855–66. DOI: 10.1038/clpt.2011.45. PMID: 21471964. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=79956320912&origin=inward.

Article12. Olry de Labry Lima A, Salamanca-Fernández E, Alegre Del Rey EJ, Matas Hoces A, González Vera MÁ, Bermúdez Tamayo C. 2021; Safety considerations during prescription of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), through a review of systematic reviews. An Sist Sanit Navar. 44:261–73. DOI: 10.23938/ASSN.0965. PMID: 34170889. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=85114958191&origin=inward.

Article13. White WB, Faich G, Borer JS, Makuch RW. 2003; Cardiovascular thrombotic events in arthritis trials of the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib. Am J Cardiol. 92:411–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00659-3. PMID: 12914871. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0041562646&origin=inward.

Article14. Grosser T, Fries S, FitzGerald GA. 2006; Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of COX-2 inhibition: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. J Clin Invest. 116:4–15. DOI: 10.1172/JCI27291. PMID: 16395396. PMCID: PMC1323269. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=31044441042&origin=inward.

Article15. Marsico F, Paolillo S, Filardi PP. 2017; NSAIDs and cardiovascular risk. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 18 Suppl 1:Special Issue on The State of the Art for the Practicing Cardiologist: The 2016 Conoscere E Curare Il Cuore (CCC) Proceedings from the CLI Foundation. e40–3. DOI: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000443. PMID: 27652819. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=84988628639&origin=inward.

Article16. Sondhi SM, Dinodia M, Singh J, Rani R. 2007; Heterocyclic compounds as anti-inflammatory agents. Curr Bioact Compd. 3:91–108. DOI: 10.2174/157340707780809554. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=34250329964&origin=inward.

Article17. Kurumbail RG, Stevens AM, Gierse JK, McDonald JJ, Stegeman RA, Pak JY, et al. 1996; Structural basis for selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by anti-inflammatory agents. Nature. 384:644–8. Erratum in: Nature 1997; 385: 555. DOI: 10.1038/384644a0. PMID: 8967954. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0030461132&origin=inward.

Article18. Zarghi A, Arfaei S. 2011; Selective COX-2 inhibitors: a review of their structure-activity relationships. Iran J Pharm Res. 10:655–83. PMID: 24250402. PMCID: PMC3813081.19. Sztanke K, Markowski W, Świeboda R, Polak B. 2010; Lipophilicity of novel antitumour and analgesic active 8-aryl-2,6,7,8-tetrahydroimidazo[2,1-c][1,2,4]triazine-3,4-dione derivatives determined by reversed-phase HPLC and computational methods. Eur J Med Chem. 45:2644–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.068. PMID: 20172631. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=77950860910&origin=inward.

Article20. Sztanke K, Fidecka S, Kedzierska E, Karczmarzyk Z, Pihlaja K, Matosiuk D. 2005; Antinociceptive activity of new imidazolidine carbonyl derivatives. Part 4. Synthesis and pharmacological activity of 8-aryl-3,4-dioxo-2H,8H-6,7-dihydroimidazo[2,1-c] [1,2,4]triazines. Eur J Med Chem. 40:127–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.09.020. PMID: 15694647. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=13444256283&origin=inward.21. Asadi P, Alvani M, Hajhashemi V, Rostami M, Khodarahmi G. 2021; Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking study on triazine based derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents. J Mol Struct. 1243:130760. DOI: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130760. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=85108717914&origin=inward.

Article22. Gawade SP. 2012; Acetic acid induced painful endogenous infliction in writhing test on mice. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 3:348. DOI: 10.4103/0976-500X.103699. PMID: 23326113. PMCID: PMC3543562. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=84878725549&origin=inward.

Article23. Tjølsen A, Berge OG, Hunskaar S, Rosland JH, Hole K. 1992; The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain. 51:5–17. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90003-T. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0026674117&origin=inward.

Article24. Hajhashemi V, Amin B. 2011; Effect of glibenclamide on antinociceptive effects of antidepressants of different classes. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 66:321–5. DOI: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200023. PMID: 21484053. PMCID: PMC3059867. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=79955488137&origin=inward.

Article25. Hajhashemi V, Dehdashti K. 2014; Antinociceptive effect of clavulanic acid and its preventive activity against development of morphine tolerance and dependence in animal models. Res Pharm Sci. 9:315–21. PMID: 25657803. PMCID: PMC4317999.26. Hajhashemi V, Sajjadi SE, Zomorodkia M. 2011; Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Bunium persicum essential oil, hydroalcoholic and polyphenolic extracts in animal models. Pharm Biol. 49:146–51. DOI: 10.3109/13880209.2010.504966. PMID: 20942602. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=79251624659&origin=inward.27. Hunskaar S, Hole K. 1987; The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 30:103–14. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. PMID: 3614974. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0023223448&origin=inward.

Article28. Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. 1992; Antinociceptive actions of spinal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the formalin test in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 263:136–46. PMID: 1403779. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=0026673173&origin=inward.29. Choi CH, Kim WM, Lee HG, Jeong CW, Kim CM, Lee SH, et al. 2010; Roles of opioid receptor subtype in the spinal antinociception of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor. Korean J Pain. 23:236–41. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2010.23.4.236. PMID: 21217886. PMCID: PMC3000619.

Article30. Gunn A, Bobeck EN, Weber C, Morgan MM. 2011; The influence of non-nociceptive factors on hot-plate latency in rats. J Pain. 12:222–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.011. PMID: 20797920. PMCID: PMC3312470. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=79551597726&origin=inward.

Article31. Malmberg AB, Bannon AW. 1999; Models of nociception: hot-plate, tail-flick, and formalin tests in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 6:8.9.1–15. DOI: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0809s06. PMID: 18428666.

Article32. Le Bars D, Gozariu M, Cadden SW. 2001; Animal models of nociception. Pharmacol Rev. 53:597–652. DOI: 10.4103/0253-7613.27702. PMID: 11734620. PMID: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?partnerID=HzOxMe3b&scp=33749634684&origin=inward.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antinociceptive Effects of Amikacin on Neuropathic Pain in Rats

- Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of sitagliptin in animal models and possible mechanisms involved in the antinociceptive activity

- New antiepileptic drugs. II. Clinical use

- Antinociceptive Effects of Tramadol on the Neuropathic Pain in Rats

- The antinociceptive effect of artemisinin on the inflammatory pain and role of GABAergic and opioidergic systems