Yeungnam Univ J Med.

2018 Jun;35(1):84-88. 10.12701/yujm.2018.35.1.84.

A successful management after preterm delivery in a patient with severe sepsis during third-trimester pregnancy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. swshim@cu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea.

- KMID: 2415738

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12701/yujm.2018.35.1.84

Abstract

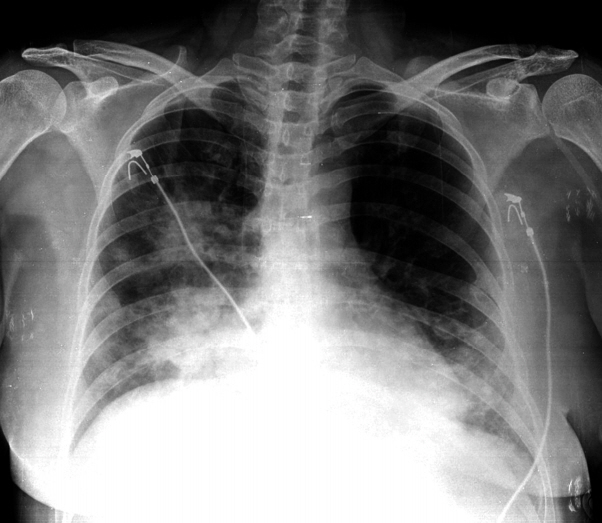

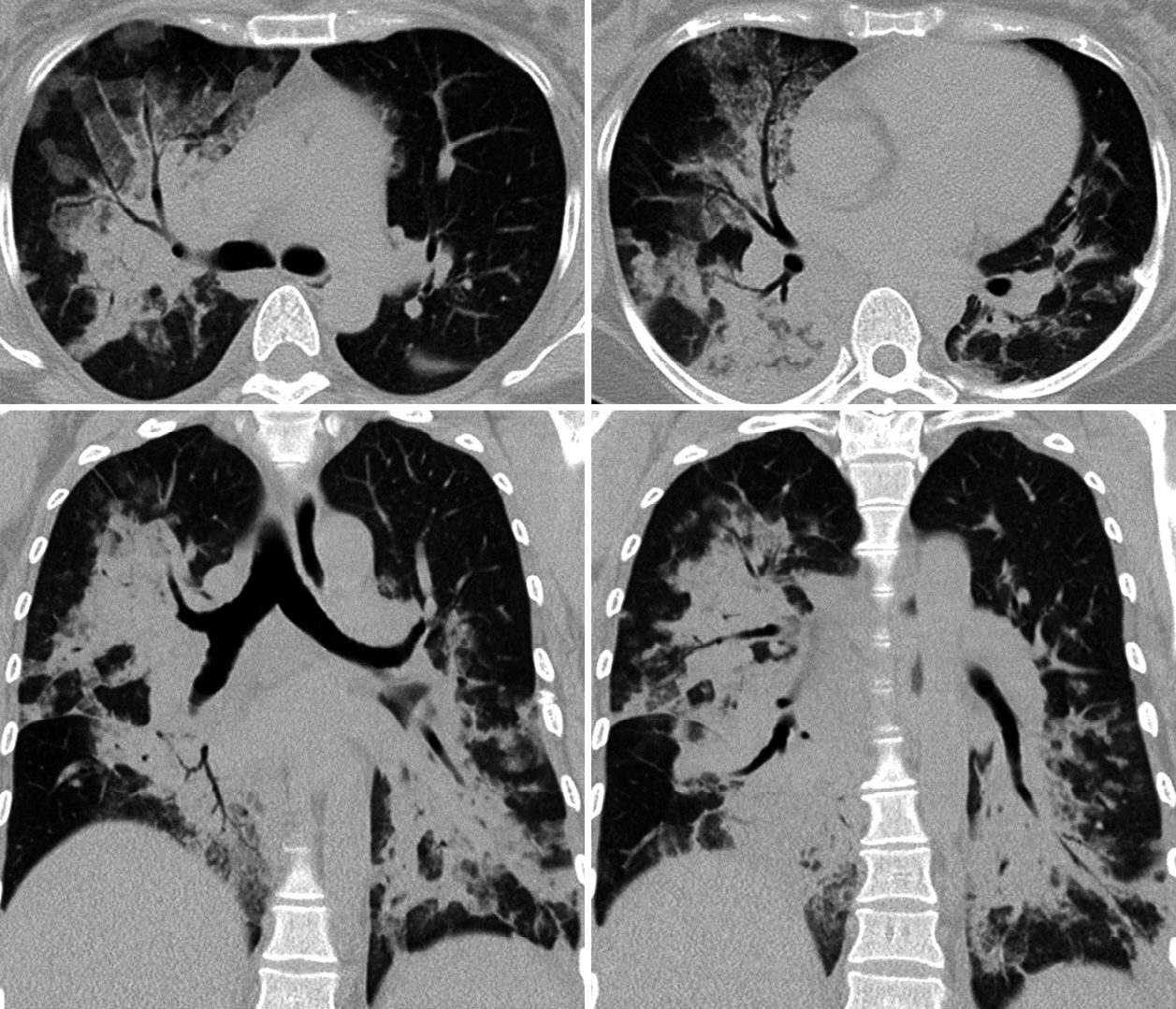

- A 33-year-old woman visited the emergency department presenting with fever and dyspnea. She was pregnant with gestational age of 31 weeks and 6 days. She had dysuria for 7 days, and fever and dyspnea for 1 day. The vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 110/70 mmHg, heart rate 118 beats/minute, respiratory rate 28/minute, body temperature 38.7℃, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 84% during inhalation of 5 liters of oxygen by nasal prongs. Crackles were heard over both lung fields. There were no signs of uterine contractions. Chest X-ray and chest computed tomography scan showed multiple consolidations and air bronchograms in both lungs. According to urinalysis, there was pyuria and microscopic hematuria. She was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infection (UTI) that progressed to severe sepsis and acute respiratory failure. We found extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in the blood culture and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the sputum culture. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with administration of antibiotics and supplementation of high-flow oxygen. On hospital day 2, hypoxemia was aggravated. She underwent endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. After 3 hours, fetal distress was suspected. Under 100% fraction of inspired oxygen, her oxygen partial pressure was 87 mmHg in the arterial blood. She developed acute kidney injury and thrombocytopenia. We diagnosed her with multi-organ failure due to severe sepsis. After an emergent cesarean section, pneumonia, UTI, and other organ failures gradually recovered. The patient and baby were discharged soon thereafter.

MeSH Terms

-

Acute Kidney Injury

Adult

Anoxia

Anti-Bacterial Agents

beta-Lactamases

Blood Pressure

Body Temperature

Cesarean Section

Dyspnea

Dysuria

Emergency Service, Hospital

Escherichia coli

Female

Fetal Distress

Fever

Gestational Age

Heart Rate

Hematuria

Humans

Inhalation

Intensive Care Units

Intubation, Intratracheal

Lung

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Oximetry

Oxygen

Partial Pressure

Pneumonia

Pregnancy Complications, Infectious

Pregnancy*

Pyuria

Respiration, Artificial

Respiratory Insufficiency

Respiratory Rate

Respiratory Sounds

Sepsis*

Sputum

Thorax

Thrombocytopenia

Urinalysis

Urinary Tract Infections

Uterine Contraction

Vital Signs

Anti-Bacterial Agents

Oxygen

beta-Lactamases

Figure

Reference

-

1. Fernández-Pérez ER, Salman S, Pendem S, Farmer JC. Sepsis during pregnancy. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33(10 Suppl):S286–93.

Article2. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014; 2:e323–33.

Article3. Snyder CC, Barton JR, Habli M, Sibai BM. Severe sepsis and septic shock in pregnancy: indications for delivery and maternal and perinatal outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013; 26:503–6.

Article4. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992; 20:864–74.5. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:1546–54.

Article6. Mabie WC, Barton JR, Sibai B. Septic shock in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 90:553–61.

Article7. Blanco JD, Gibbs RS, Castaneda YS. Bacteremia in obstetrics: clinical course. Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 58:621–5.8. Ledger WJ, Norman M, Gee C, Lewis W. Bacteremia on an obstetric-gynecologic service. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975; 121:205–12.

Article9. Bryan CS, Reynolds KL, Moore EE. Bacteremia in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 64:155–8.10. Afessa B, Green B, Delke I, Koch K. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, organ failure, and outcome in critically ill obstetric patients treated in an ICU. Chest. 2001; 120:1271–7.

Article11. Acosta CD, Kurinczuk JJ, Lucas DN, Tuffnell DJ, Sellers S, Knight M, et al. Severe maternal sepsis in the UK, 2011-2012: a national case-control study. PLoS Med. 2014; 11:e1001672.

Article12. Nakou A, Woodhead M, Torres A. MRSA as a cause of community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2009; 34:1013–4.

Article13. Vardakas KZ, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME. Incidence, characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe community acquired-MRSA pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2009; 34:1148–58.

Article14. Meier S, Weber R, Zbinden R, Ruef C, Hasse B. Extendedspectrum β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative pathogens in community-acquired urinary tract infections: an increasing challenge for antimicrobial therapy. Infection. 2011; 39:333–40.

Article15. Barton JR, Sibai BM. Severe sepsis and septic shock in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:689–706.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Successful Conservative Management for Spontaneous Hemoperitoneum in the 3rd Trimester Pregnancy

- A Successful Delivery of Woman with Second-trimester Ruptured Membranes

- Successful term pregnancy after transabdominal cerclage with previous second trimester loss following vaginal radical trachelectomy

- Prevalence of vaginal microorganisms among pregnant women according to trimester and association with preterm birth

- Pregnancy outcome after cervical conization: risk factors for preterm delivery and the efficacy of prophylactic cerclage