Ann Lab Med.

2017 Mar;37(2):97-107. 10.3343/alm.2017.37.2.97.

Recommendations for Optimizing Tuberculosis Treatment: Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, Pharmacogenetics, and Nutritional Status Considerations

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine and Genetics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. suddenbz@skku.edu

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. wjkoh@skku.edu

- 3Department of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2373626

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2017.37.2.97

Abstract

- Although tuberculosis is largely a curable disease, it remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although the standard 6-month treatment regimen is highly effective for drug-susceptible tuberculosis, the use of multiple drugs over long periods of time can cause frequent adverse drug reactions. In addition, some patients with drug-susceptible tuberculosis do not respond adequately to treatment and develop treatment failure and drug resistance. Response to tuberculosis treatment could be affected by multiple factors associated with the host-pathogen interaction including genetic factors and the nutritional status of the host. These factors should be considered for effective tuberculosis control. Therefore, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), which is individualized drug dosing guided by serum drug concentrations during treatment, and pharmacogenetics-based personalized dosing guidelines of anti-tuberculosis drugs could reduce the incidence of adverse drug reactions and increase the likelihood of successful treatment outcomes. Moreover, assessment and management of comorbid conditions including nutritional status could improve anti-tuberculosis treatment response.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Biologic Agents in the Era of Precision Medicine

Soo-Youn Lee

Ann Lab Med. 2020;40(2):95-96. doi: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.2.95.

Reference

-

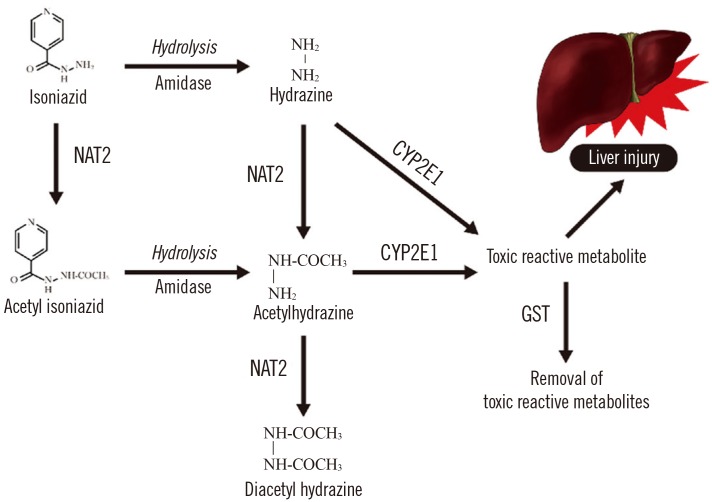

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2016. WHO/HTM/TB/2015.22. Geneva: World Health Organization;2016. Accessed on Nov 2016. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.2. Shin HJ, Kwon YS. Treatment of drug susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2015; 78:161–167. PMID: 26175767.3. Horsburgh CR Jr, Barry CE 3rd, Lange C. Treatment of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2149–2160. PMID: 26605929.4. Yew WW, Koh WJ. Emerging strategies for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: promise and limitations? Korean J Intern Med. 2016; 31:15–29. PMID: 26767853.5. Marra F, Marra CA, Bruchet N, Richardson K, Moadebi S, Elwood RK, et al. Adverse drug reactions associated with first-line anti-tuberculosis drug regimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007; 11:868–875. PMID: 17705952.6. Lv X, Tang S, Xia Y, Wang X, Yuan Y, Hu D, et al. Adverse reactions due to directly observed treatment strategy therapy in chinese tuberculosis patients: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e65037. PMID: 23750225.7. Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2007; 4:e238. PMID: 17676945.8. Yew WW, Leung CC. Antituberculosis drugs and hepatotoxicity. Respirology. 2006; 11:699–707. PMID: 17052297.9. Pasipanodya JG, McIlleron H, Burger A, Wash PA, Smith P, Gumbo T. Serum drug concentrations predictive of pulmonary tuberculosis outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2013; 208:1464–1473. PMID: 23901086.10. Mah A, Kharrat H, Ahmed R, Gao Z, Der E, Hansen E, et al. Serum drug concentrations of INH and RMP predict 2-month sputum culture results in tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015; 19:210–215. PMID: 25574921.11. Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, Daley CL, Etkind SC, Friedman LN, et al. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 167:603–662. PMID: 12588714.12. WHO. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes 4th ed WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2009. Accessed on Nov 2016. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/tb_treatmentguidelines/en/.13. Satyaraddi A, Velpandian T, Sharma SK, Vishnubhatla S, Sharma A, Sirohiwal A, et al. Correlation of plasma anti-tuberculosis drug levels with subsequent development of hepatotoxicity. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014; 18:188–195. PMID: 24429311.14. Pasipanodya JG, Srivastava S, Gumbo T. Meta-analysis of clinical studies supports the pharmacokinetic variability hypothesis for acquired drug resistance and failure of antituberculosis therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:169–177. PMID: 22467670.15. Srivastava S, Pasipanodya JG, Meek C, Leff R, Gumbo T. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis not due to noncompliance but to between-patient pharmacokinetic variability. J Infect Dis. 2011; 204:1951–1959. PMID: 22021624.16. Alsultan A, Peloquin CA. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis: an update. Drugs. 2014; 74:839–854. PMID: 24846578.17. Reynolds J, Heysell SK. Understanding pharmacokinetics to improve tuberculosis treatment outcome. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014; 10:813–823. PMID: 24597717.18. Sotgiu G, Alffenaar JW, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, Spanevello A, Piana A, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring: how to improve drug dosage and patient safety in tuberculosis treatment. Int J Infect Dis. 2015; 32:101–104. PMID: 25809764.19. Ma Q, Lu AY. Pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, and individualized medicine. Pharmacol Rev. 2011; 63:437–459. PMID: 21436344.20. Pirazzoli A, Recchia G. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics: are they still promising? Pharmacol Res. 2004; 49:357–361. PMID: 15202515.21. Sun F, Chen Y, Xiang Y, Zhan S. Drug-metabolising enzyme polymorphisms and predisposition to anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12:994–1002. PMID: 18713495.22. Wang PY, Xie SY, Hao Q, Zhang C, Jiang BF. NAT2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012; 16:589–595. PMID: 22409928.23. Li C, Long J, Hu X, Zhou Y. GSTM1 and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms and risk of anti-tuberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity: an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013; 32:859–868. PMID: 23377313.24. Oshikoya KA, Sammons HM, Choonara I. A systematic review of pharmacokinetics studies in children with protein-energy malnutrition. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 66:1025–1035. PMID: 20552179.25. Jeremiah K, Denti P, Chigutsa E, Faurholt-Jepsen D, PrayGod G, Range N, et al. Nutritional supplementation increases rifampin exposure among tuberculosis patients coinfected with HIV. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:3468–3474. PMID: 24709267.26. Hatsuda K, Takeuchi M, Ogata K, Sasaki Y, Kagawa T, Nakatsuji H, et al. The impact of nutritional state on the duration of sputum positivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015; 19:1369–1375. PMID: 26467590.27. Zeng J, Wu G, Yang W, Gu X, Liang W, Yao Y, et al. A serum vitamin D level <25nmol/l pose high tuberculosis risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0126014. PMID: 25938683.28. Pareek M, Innes J, Sridhar S, Grass L, Connell D, Woltmann G, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and TB disease phenotype. Thorax. 2015; 70:1171–1180. PMID: 26400877.29. Junaid K, Rehman A, Saeed T, Jolliffe DA, Wood K, Martineau AR. Genotype-independent association between profound vitamin D deficiency and delayed sputum smear conversion in pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15:275. PMID: 26193879.30. Kwon YS, Jeong BH, Koh WJ. Tuberculosis: clinical trials and new drug regimens. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014; 20:280–286. PMID: 24614239.31. Kwon YS, Koh WJ. Synthetic investigational new drugs for the treatment of tuberculosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016; 25:183–193.32. Wilby KJ, Ensom MH, Marra F. Review of evidence for measuring drug concentrations of first-line antitubercular agents in adults. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014; 53:873–890. PMID: 25172553.33. Peloquin CA. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis. Drugs. 2002; 62:2169–2183. PMID: 12381217.34. WHO. A practical handbook on the pharmacovigilance of medicines used in the treatment of tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization;2012. Accessed on Nov 2016. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/pharmacovigilance_tb/en/.35. Magis-Escurra C, van den Boogaard J, Ijdema D, Boeree M, Aarnoutse R. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 25:83–86. PMID: 22179055.36. Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE, editors. Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics. 5th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences;2012.37. Heysell SK, Moore JL, Keller SJ, Houpt ER. Therapeutic drug monitoring for slow response to tuberculosis treatment in a state control program, Virginia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:1546–1553. PMID: 20875279.38. Perwitasari DA, Atthobari J, Wilffert B. Pharmacogenetics of isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Rev. 2015; 47:222–228. PMID: 26095714.39. Sprague DA, Ensom MH. Limited-sampling strategies for anti-infective agents: systematic review. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009; 62:392–401. PMID: 22478922.40. Wang L, McLeod HL, Weinshilboum RM. Genomics and drug response. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:1144–1153. PMID: 21428770.41. Matsumoto T, Ohno M, Azuma J. Future of pharmacogenetics-based therapy for tuberculosis. Pharmacogenomics. 2014; 15:601–607. PMID: 24798717.42. Selinski S, Blaszkewicz M, Ickstadt K, Hengstler JG, Golka K. Improvements in algorithms for phenotype inference: the NAT2 example. Curr Drug Metab. 2014; 15:233–249. PMID: 24524665.43. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, Muller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Gong L, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014; 15:209–217. PMID: 24479687.44. Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, Gong L, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 92:414–417. PMID: 22992668.45. McDonagh EM, Boukouvala S, Aklillu E, Hein DW, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for N-acetyltransferase 2. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014; 24:409–425. PMID: 24892773.46. Azuma J, Ohno M, Kubota R, Yokota S, Nagai T, Tsuyuguchi K, et al. NAT2 genotype guided regimen reduces isoniazid-induced liver injury and early treatment failure in the 6-month four-drug standard treatment of tuberculosis: a randomized controlled trial for pharmacogenetics-based therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69:1091–1101. PMID: 23150149.47. Jung JA, Kim TE, Lee H, Jeong BH, Park HY, Jeon K, et al. A proposal for an individualized pharmacogenetic-guided isoniazid dosage regimen for patients with tuberculosis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015; 9:5433–5438.48. WHO. Guideline: Nutritional care and support for patients with tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Oragnization;2013. Accessed on Nov 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94836/1/9789241506410_eng.pdf.49. Hood ML. A narrative review of recent progress in understanding the relationship between tuberculosis and protein energy malnutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013; 67:1122–1128. PMID: 23942176.50. Grobler L, Nagpal S, Sudarsanam TD, Sinclair D. Nutritional supplements for people being treated for active tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; Cd006086. PMID: 27355911.51. WHO. IMAI district clinician manual: Hospital care for adolescents and adults. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Oragnization;2011.52. McPherson RA, Pincus MR, editors. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences;2011.53. Choi R, Kim HT, Lim Y, Kim MJ, Kwon OJ, Jeon K, et al. Serum concentrations of trace elements in patients with tuberculosis and its association with treatment outcome. Nutrients. 2015; 7:5969–5981. PMID: 26197334.54. Vilcheze C, Hartman T, Weinrick B, Jacobs WR Jr. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is extraordinarily sensitive to killing by a vitamin C-induced Fenton reaction. Nat Commun. 2013; 4:1881. PMID: 23695675.55. Daley P, Jagannathan V, John KR, Sarojini J, Latha A, Vieth R, et al. Adjunctive vitamin D for treatment of active tuberculosis in India: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15:528–534. PMID: 25863562.56. Cegielski P, Vernon A. Tuberculosis and vitamin D: what's the rest of the story? Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15:489–490. PMID: 25863560.57. Koo HK, Lee JS, Jeong YJ, Choi SM, Kang HJ, Lim HJ, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and changes in serum vitamin D levels with treatment among tuberculosis patients in South Korea. Respirology. 2012; 17:808–813. PMID: 22449254.58. Choi CJ, Seo M, Choi WS, Kim KS, Youn SA, Lindsey T, et al. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and lung function among Korean adults in Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2008-2010. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98:1703–1710. PMID: 23533242.59. Kim JH, Park JS, Cho YJ, Yoon HI, Song JH, Lee CT, et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level: an independent risk factor for tuberculosis? Clin Nutr. 2014; 33:1081–1086. PMID: 24332595.60. Hong JY, Kim SY, Chung KS, Kim EY, Jung JY, Park MS, et al. Association between vitamin D deficiency and tuberculosis in a Korean population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014; 18:73–78. PMID: 24365556.61. Lexicomp. Drug Information Handbook. 23th ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp;2014.62. Peloquin CA. Using therapeutic drug monitoring to dose the antimycobacterial drugs. Clin Chest Med. 1997; 18:79–87. PMID: 9098612.63. Kurose K, Sugiyama E, Saito Y. Population differences in major functional polymorphisms of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics-related genes in Eastern Asians and Europeans: implications in the clinical trials for novel drug development. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012; 27:9–54. PMID: 22123129.64. Kang TS, Jin SK, Lee JE, Woo SW, Roh J. Comparison of genetic polymorphisms of the NAT2 gene between Korean and four other ethnic groups. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009; 34:709–718. PMID: 20175805.65. Lee SY, Lee KA, Ki CS, Kwon OJ, Kim HJ, Chung MP, et al. Complete sequencing of a genetic polymorphism in NAT2 in the Korean population. Clin Chem. 2002; 48:775–777. PMID: 11978608.66. Lee KM, Park SK, Kim SU, Doll MA, Yoo KY, Ahn SH, et al. N-acetyltransferase (NAT1, NAT2) and glutathione S-transferase (GSTM1, GSTT1) polymorphisms in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003; 196:179–186. PMID: 12860276.67. Bertrand J, Verstuyft C, Chou M, Borand L, Chea P, Nay KH, et al. Dependence of efavirenz- and rifampicin-isoniazid-based antituberculosis treatment drug-drug interaction on CYP2B6 and NAT2 genetic polymorphisms: ANRS 12154 study in Cambodia. J Infect Dis. 2014; 209:399–408. PMID: 23990572.68. Garte S, Gaspari L, Alexandrie AK, Ambrosone C, Autrup H, Autrup JL, et al. Metabolic gene polymorphism frequencies in control populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001; 10:1239–1248. PMID: 11751440.69. Sabbagh A, Langaney A, Darlu P, Gerard N, Krishnamoorthy R, Poloni ES. Worldwide distribution of NAT2 diversity: implications for NAT2 evolutionary history. BMC Genet. 2008; 9:21. PMID: 18304320.70. Sabbagh A, Darlu P, Crouau-Roy B, Poloni ES. Arylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) genetic diversity and traditional subsistence: a worldwide population survey. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e18507. PMID: 21494681.71. Villamor E, Fawzi WW. Effects of vitamin a supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005; 18:446–464. PMID: 16020684.72. Gupta KB, Gupta R, Atreja A, Verma M, Vishvkarma S. Tuberculosis and nutrition. Lung India. 2009; 26:9–16. PMID: 20165588.73. Verrall AJ, Netea MG, Alisjahbana B, Hill PC, van Crevel R. Early clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a new frontier in prevention. Immunology. 2014; 141:506–513. PMID: 24754048.74. Madebo T, Lindtjorn B, Aukrust P, Berge RK. Circulating antioxidants and lipid peroxidation products in untreated tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003; 78:117–122. PMID: 12816780.75. Rodriguez GM, Neyrolles O. Metallobiology of Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2014; 2.76. Minchella PA, Donkor S, Owolabi O, Sutherland JS, McDermid JM. Complex anemia in tuberculosis: the need to consider causes and timing when designing interventions. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:764–772. PMID: 25428413.77. Hood MI, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012; 10:525–537. PMID: 22796883.78. Shi X, Darwin KH. Copper homeostasis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Metallomics. 2015; 7:929–934. PMID: 25614981.79. Neyrolles O, Wolschendorf F, Mitra A, Niederweis M. Mycobacteria, metals, and the macrophage. Immunol Rev. 2015; 264:249–263. PMID: 25703564.80. Arthur JR, McKenzie RC, Beckett GJ. Selenium in the immune system. J Nutr. 2003; 133:1457s–1459s. PMID: 12730442.81. Hoffman AE, DeStefano M, Shoen C, Gopinath K, Warner DF, Cynamon M, et al. Co(II) and Cu(II) pyrophosphate complexes have selectivity and potency against Mycobacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Med Chem. 2013; 70:589–593. PMID: 24211634.82. Perez-Guzman C, Vargas MH, Quinonez F, Bazavilvazo N, Aguilar A. A cholesterol-rich diet accelerates bacteriologic sterilization in pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 2005; 127:643–651. PMID: 15706008.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pharmacogenetics in Psychotropic Drugs

- Emerging strategies for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: promise and limitations?

- Monitoring Ethambutol-Induced Optic Neuropathy in Tuberculosis Treatment: A Systematic Review of Guidelines and Recommendations

- Pharmacogenetics of anesthetics

- Current Pharmacogenetics in Psychiatry