J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2010 Mar;51(3):406-417.

Comparison of the Efficacy of Topical Antihistamine/Mast Cell Stabilizers in vitro

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Medical Research Institue, Busan, Korea. jongsool@pusan.ac.kr

- 2Shinsegae Eye Clinic, Ulsan, Korea.

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the biologic effects of topical anti-allergic agents with H1-receptor antagonism and inhibition of histamine release from mast cells in the cultured conjunctival cells of patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis in vitro.

METHODS

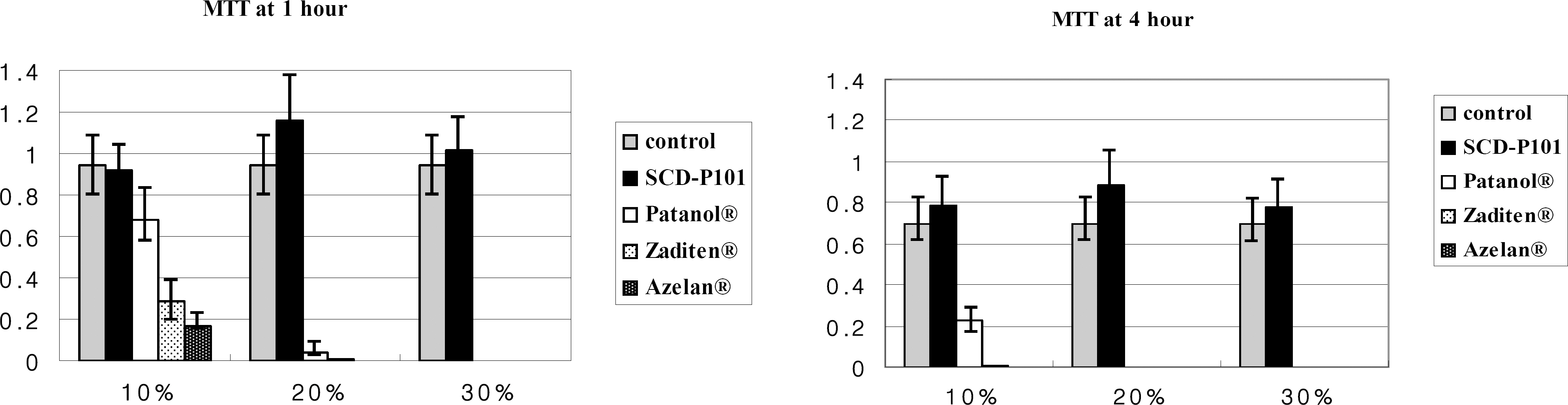

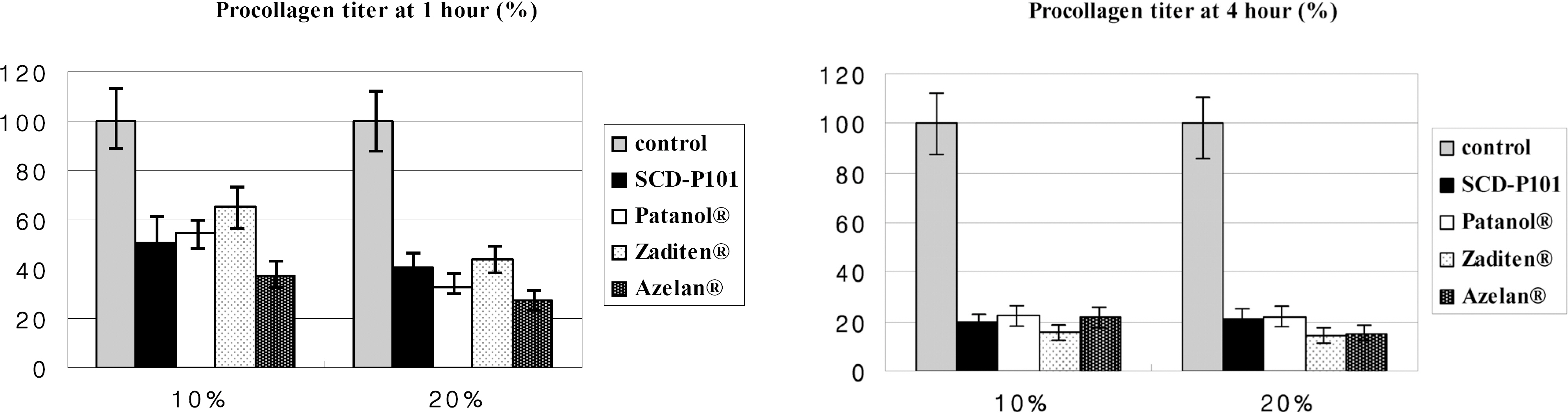

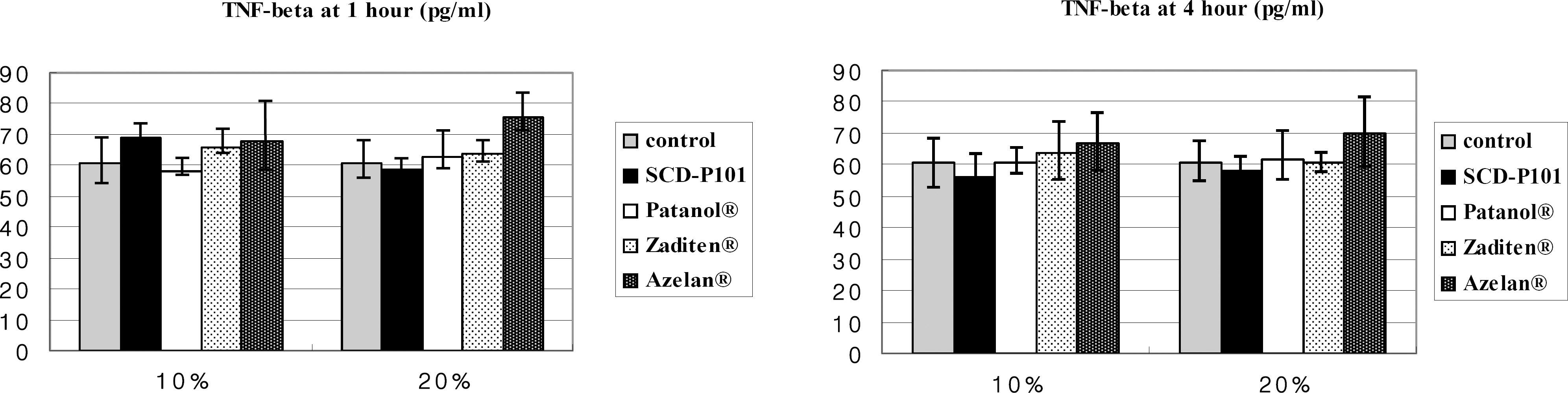

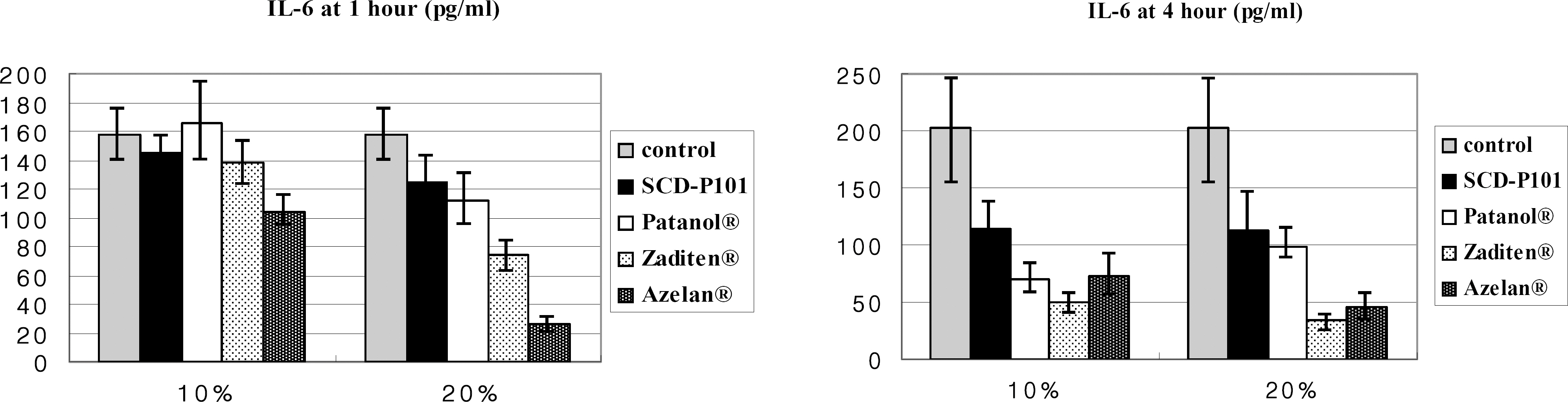

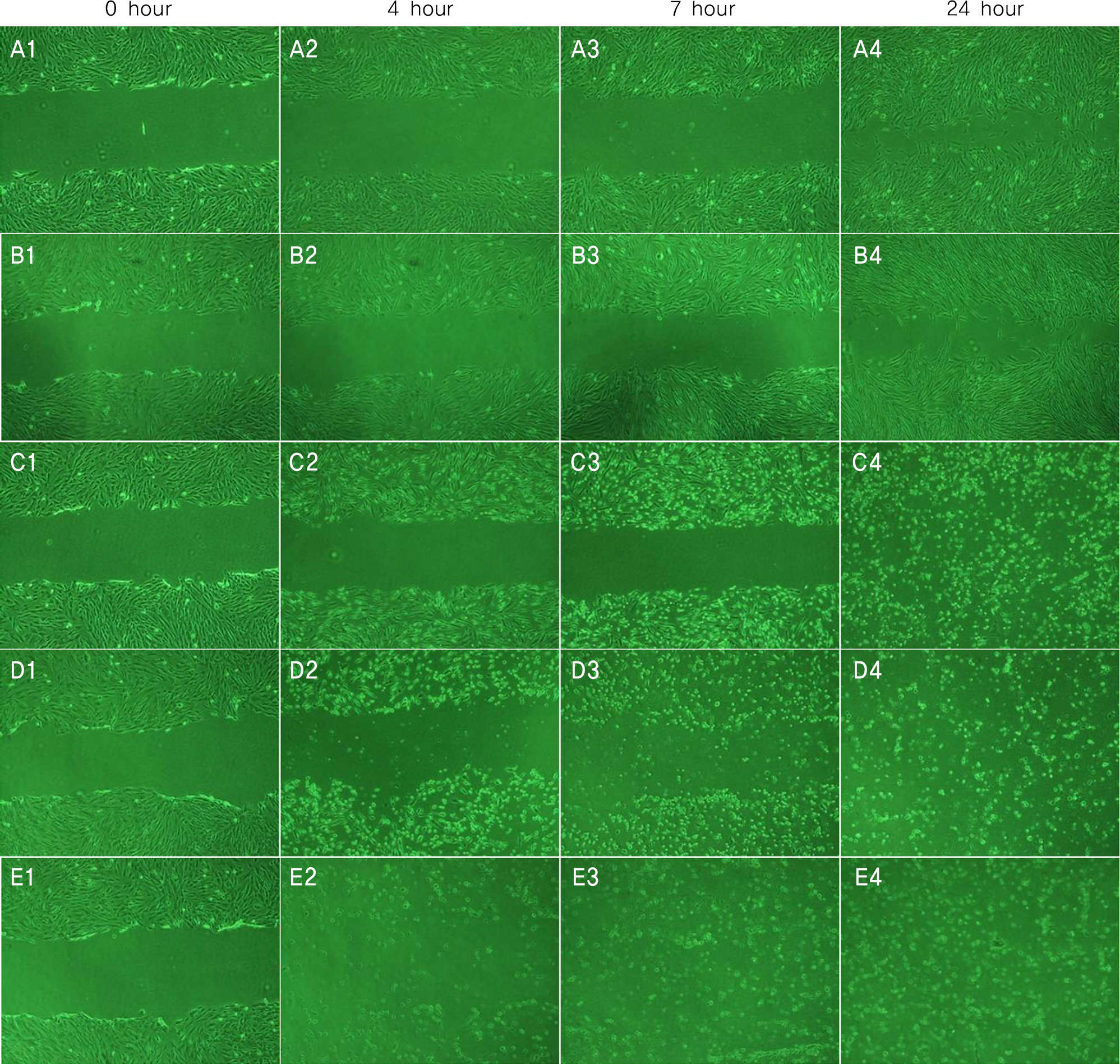

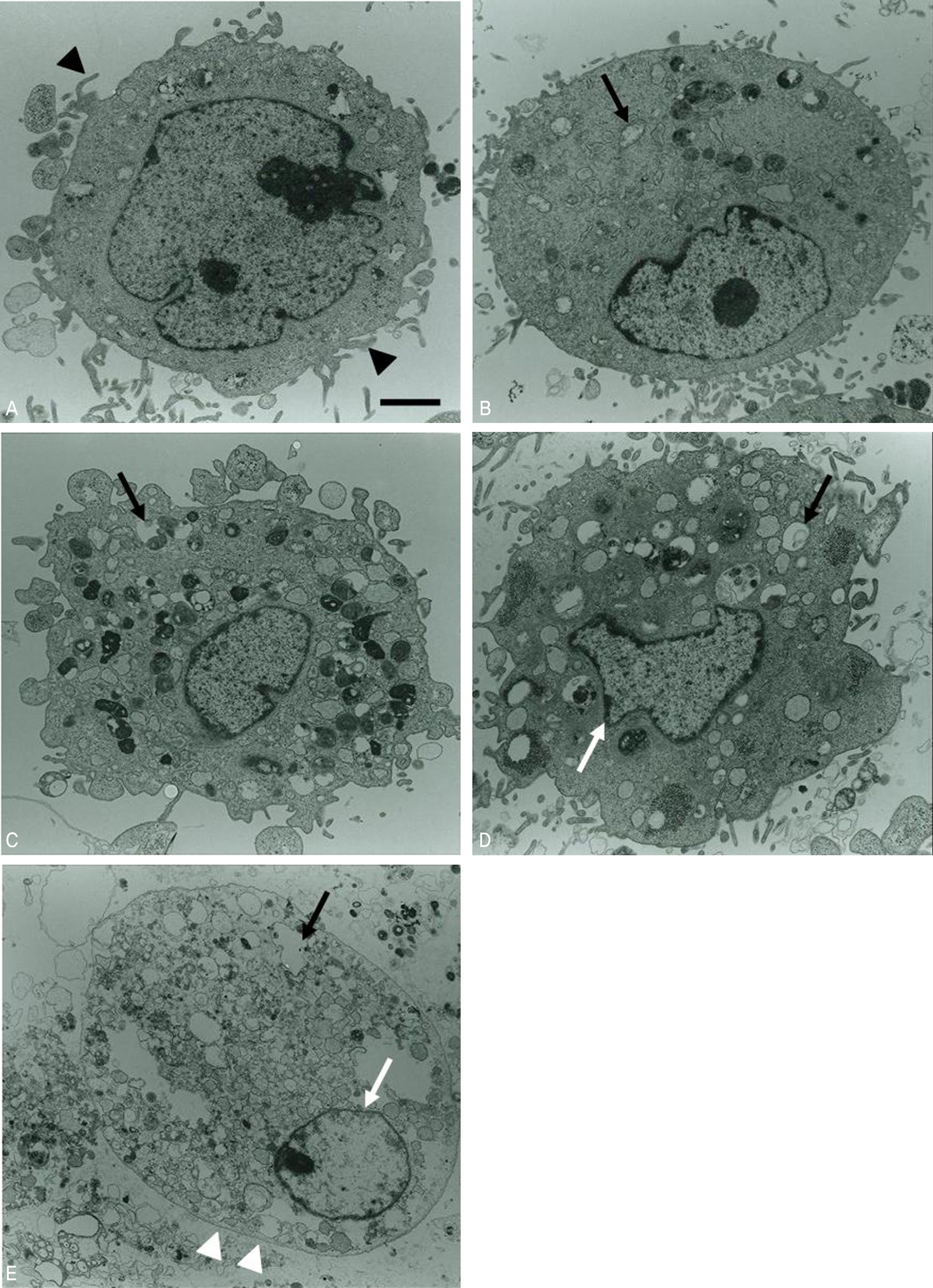

Conjunctival cells of vernal keratoconjunctivitis were exposed to the anti-allergic agents SCD-P101 (Fexofenadine, Samchundang, Korea), Patanol(R) (Alcon, USA), Zaditen(R) (Novartis, USA), and Azelan(R) (Taejoon, Korea). Efficacy of the topical antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers was evaluated using the MTT assay, measuring the concentration of procollagen and inflammatory cytokines. Cell damage was determined using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay with dilution rates of 10, 20, and 30% and compared with the balanced salt solution-treated group. Cellular morphologic results were examined by inverted light microscopy and transmission electromicroscopy.

RESULTS

Metabolic activity of conjunctival cells decreased at higher concentrations and longer exposure durations, except for the SCD-P101 agent. The procollagen, laminin, IL-6 and IL-8 titers tended to be lower than that of the control in the eyes exposed to all the anti-allergic drugs tested in this study, but the concentration of TNF-beta was similar to that of the control group. Zaditen(R) and Azelan(R) tended to show a greater LDH titer and edema, as well as cytoplasmic and nuclear degeneration of the conjunctival cells than did SCD-P101 or Patanol(R).

CONCLUSIONS

Cellular metabolic activity was the highest in the new anti-allergic agent SCD-P101. SCD-P101 and Patanol(R) caused marginally less damage to cultured conjunctival cells than did Zaditen(R) and Azelan(R).

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Anti-Allergic Agents

Conjunctivitis, Allergic

Cytokines

Cytoplasm

Edema

Eye

Histamine Release

Humans

Interleukin-6

Interleukin-8

L-Lactate Dehydrogenase

Laminin

Light

Lymphotoxin-alpha

Mast Cells

Microscopy

Procollagen

Anti-Allergic Agents

Cytokines

Interleukin-6

Interleukin-8

L-Lactate Dehydrogenase

Laminin

Lymphotoxin-alpha

Procollagen

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Holgate ST, Lack G. Improving the management of atopic disease. Arch Dis Child. 2005; 90:826–31.

Article2. Weeke ER. Epidemiology of hay fever and perennial allergic rhinitis. Monoger Allergy. 1987; 21:1–20.3. Foster CS. Immunologic disorders of the conjunctiva, cornea, and sclera In: Albert PM, Jakobiec FA, eds. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company;1994. 2:chap. 65.4. Bielory L. Therapeutic targets in allergic eye disease. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2001; 22:25–8.

Article5. Mosmann TJ. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxic assays. J Immunolo Methods. 1983; 65:55–63.6. Schultz BL. Pharmacology of ocular allergy. Current Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 6:383–9.

Article7. Abelson MB, Smith L, Chapin M. Ocular allergic disease: Mechanisms, disease abdominal, treat. Ocul Su. 2003; 1:127–49.8. McGill JI. A review of the use of olopatadine in allergic conjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2004; 25:171–9.

Article9. Frossard N, Strolin-Benedetti M, Purohit A, Pauli G. Inhibition of allergen-induced wheal and flare reactions by levocetirizine and desloratadine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007; 65:172–9.

Article10. Spangler DL, Abelson MB, Ober A, Gomes PJ. Randomized, double-masked comparison of olopatadine ophthalmic solution, mometasone furoate monohydrate nasal spray, and fexofenadine hydrochloride tablets using the conjunctival and nasal allergen challenge models. Clin Ther. 2003; 25:2245–67.

Article11. Lee JS, Lee JE, Kim NM, Oum BS. Comparison of the conjunctival toxicity of topical ocular antiallergic agents. J Ocular Pharmacol Ther. 2008; 24:557–62.

Article12. Leonardi A, Curnow SJ, Zhan H, Calder VL. Multiple cytokines in human tear specimens in seasonal and chronic allergic eye disease and in conjunctival fibroblast cultures. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006; 36:777–84.

Article13. Sarac OI, Erdener U, Irkec M, et al. Tear eotaxin levels in giant papillary conjunctivitis associated with ocular prosthesis. Ocul Immunol Inflam. 2003; 11:223–30.

Article14. Wee RW, Wang XW, McDonnell PJ. Effect of anrtificial tears on cultured keratocytes in vitro. Cornea. 1995; 14:273–9.15. Park YS. Physiology of body fluid. Kang DH, editor. Physiology. 5th ed.Seoul: Sin-Kwang publishing & printing;2000. chap. 5.16. Luo L, Li DQ, Corrales RM, et al. Hyperosmolar saline is a proinflammatory stress on the mouse ocular surface. Eye Contact Lens. 2005; 31:186–93.

Article17. Lee JS, Oum BS. The effects of artificial tear formulation and anti-inflammatory agents on the cultured keratocyted of rabbit. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1998; 39:42–51.18. Freshney RI. The culture environment: Substrate, gas phase, medium, and temparature. 2nd ed.New York: Wiley-Liss;1987. p. 70–1.19. Lee SJ. Body fluid and acid-base balance. Kim KH, Oum YE, Kim J, editors. Physiology. Seoul: Eui-hak publishing & printing;2002. 7:chap. 20.20. Burstein NL. Preservative cytotoxic threshold for benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine digluconate in cat and rabbit corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980; 19:308–13.21. Cha SH, Lee JS, Oum BS, Kim CD. Corneal epithelial cellular dysfunction from banzalkonium chloride (BAC) in vitro. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004; 32:180–4.22. Green K, Tonjum A. Influence of various agents on corneal permeability. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971; 72:897–905.

Article23. Lee JS, Jung DY, Oum BS, Kim CD. Cytotoxicity of banzalkonium chlorid on the corneal epithelial cell of rabbit. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1998; 39:1326–33.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- On the Degranulation of Mesenteric Mast Cells Caused by Antihistamine in Albino Rats: Effects of Various Dosages of Antihistamine

- A Study of Topical Corticosteroid Effect on the Rat Skin Mast Cell

- Mast Cells and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: From the Bench to the Bedside

- Experimental Study on The Role of Various Antihistaminics to Tissue Mast Cell Changes Elicited by Ultraviolet Ray Inflammation

- Diagnosis and pharmacological management of allergic conjunctivitis