Tuberc Respir Dis.

2009 Dec;67(6):536-544.

Comparison for the Effects of Triple Therapy with Salmeterol/Fluticasone Propionate and Tiotropium Bromide versus Individual Components in Patients of Severe COPD Combined with Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Korea. ryk@chonbuk.ac.kr

- 2Research Center for Pulmonary Disorders, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Korea.

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

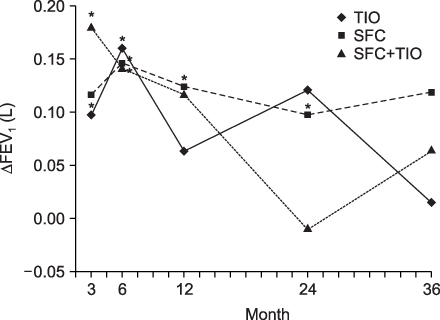

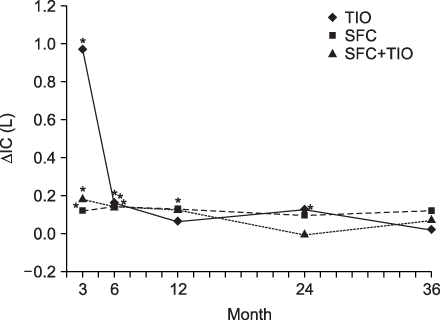

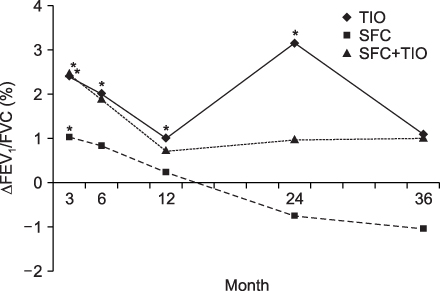

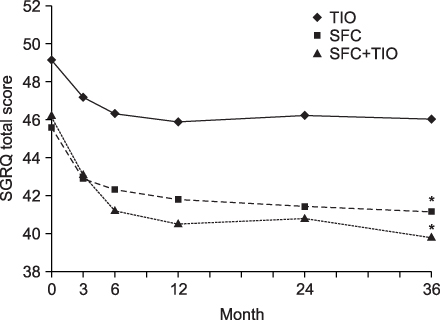

A combination of salmeterol and fluticasone propionate (SFC) and tiotropium bromide (TIO) is commonly prescribed for COPD patients but there is little data on their effectiveness, particularly in COPD patients with bronchial hyperresponsiveness. This study compared the spirometric improvement based on the change in FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and IC as well as the clinical outcomes of the therapeutic strategies with SFC and TIO versus the individual components in patients with severe COPD and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. METHODS: This study examined the spirometric data and clinical outcomes of 214 patients with COPD and hyperresponsiveness, who were divided into three groups according to the therapeutic regimen (TIO only, SFC only, and a triple therapy regimen). RESULTS: All regimen groups showed early improvement in the FEV1 and IC (at 3- and 6 months after treatment). However, long-term beneficial effects were observed only in the SFC group (at 24 months after treatment). However, these beneficial effects decreased after a 36-month follow up. In all spirometric results, the 12-, 24-, and 36-months data showed a similar degree of improvement in the three groups. The triple therapy group showed higher St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire scores and lower acute exacerbations and hospitalization. CONCLUSION: SFC can be a more important component in the pharmacological treatment of severe COPD patients with hyperresponsiveness than TIO, particularly in the spirometric and clinical outcomes.

MeSH Terms

-

Albuterol

Androstadienes

Diethylpropion

Drug Therapy, Combination

Follow-Up Studies

Hospitalization

Humans

Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive

Surveys and Questionnaires

Scopolamine Derivatives

Treatment Outcome

Fluticasone

Tiotropium Bromide

Salmeterol Xinafoate

Albuterol

Androstadienes

Diethylpropion

Scopolamine Derivatives

Figure

Reference

-

1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax. 2004. 59:Suppl 1. 1–232.2. Rhee YK, In BH, Lee YD, Lee YC, Lee HB. Prevalence of combined bronchial asthma with COPD in patients with moderate to severe air flow limitation. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2003. 54:386–394.3. Grootendorst DC, Rabe KF. Mechanisms of bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004. 1:77–87.4. Burney PG, Britton JR, Chinn S, Tattersfield AE, Papacosta AO, Kelson MC, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of bronchial reactivity in an adult population: results from a community study. Thorax. 1987. 42:38–44.5. Britton J, Pavord I, Richards K, Knox A, Wisniewski A, Wahedna I, et al. Factors influencing the occurrence of airway hyperreactivity in the general population: the importance of atopy and airway calibre. Eur Respir J. 1994. 7:881–887.6. Woolcock AJ, Peat JK, Salome CM, Yan K, Anderson SD, Schoeffel RE, et al. Prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma in a rural adult population. Thorax. 1987. 42:361–368.7. Ernst P, Ghezzo H, Becklake MR. Risk factors for bronchial hyperresponsiveness in late childhood and early adolescence. Eur Respir J. 2002. 20:635–639.8. Trigg CJ, Manolitsas ND, Wang J, Calderon MA, Mc-Aulay A, Jordan SE, et al. Placebo-controlled immunopathologic study of four months of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994. 150:17–22.9. Tashkin DP, Altose MD, Bleecker ER, Connett JE, Kanner RE, Lee WW, et al. The Lung Health Study Research Group. The lung health study: airway responsiveness to inhaled methacholine in smokers with mild to moderate airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992. 145:301–310.10. van Noord JA, Aumann JL, Janssens E, Verhaert J, Smeets JJ, Mueller A, et al. Effects of tiotropium with and without formoterol on airflow obstruction and resting hyperinflation in patients with COPD. Chest. 2006. 129:509–517.11. Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2006 [Internet]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. c2009. [place unknown]: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease;Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.12. Cazzola M, Ando F, Santus P, Ruggeri P, Di Marco F, Sanduzzi A, et al. A pilot study to assess the effects of combining fluticasone propionate/salmeterol and tiotropium on the airflow obstruction of patients with severe-to-very severe COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007. 20:556–561.13. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Goldstein R, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007. 146:545–555.14. Di Marco F, Verga M, Santus P, Morelli N, Cazzola M, Centanni S. Effect of formoterol, tiotropium, and their combination in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. Respir Med. 2006. 100:1925–1932.15. Onoue S, Misaka S, Kawabata Y, Yamada S. New treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and viable formulation/device options for inhalation therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009. 6:793–811.16. Kraft M. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exhibit common origins in any country! Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006. 174:238–240.17. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000. 160:1683–1689.18. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Decramer M, Liu D, Burkhart D, Cassino C, et al. Bronchodilator responsiveness in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008. 31:742–750.19. Fabbri LM, Romagnoli M, Corbetta L, Casoni G, Busljetic K, Turato G, et al. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:418–424.20. Rijcken B, Schouten JP, Weiss ST, Speizer FE, van der Lende R. The relationship between airway responsiveness to histamine and pulmonary function level in a random population sample. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988. 137:826–832.21. Xu X, Rijcken B, Schouten JP, Weiss ST. Airways responsiveness and development and remission of chronic respiratory symptoms in adults. Lancet. 1997. 350:1431–1434.22. Postma DS, Boezen HM. Rationale for the Dutch hypothesis. Allergy and airway hyperresponsiveness as genetic factors and their interaction with environment in the development of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2004. 126:96S–104S. discussion 59S-61S.23. Niewoehner DE. TORCH and UPLIFT: what has been learned from the COPD "mega-trials"? COPD. 2009. 6:1–3.24. Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/ fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. 177:19–26.25. Keating GM, McCormack PL. Salmeterol/fluticasone propionate: a review of its use in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drugs. 2007. 67:2383–2405.26. Seemungal T, Stockley R, Calverley P, Hagan G, Wedzicha JA. Investigating new standards for prophylaxis in reduction of exacerbations--the INSPIRE study methodology. COPD. 2007. 4:177–183.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pharmacokinetic characteristics of fluticasone, salmeterol and tiotropium after concurrent inhalation

- Optimal Bronchodilation for COPD Patients: Are All Long-Acting β₂-Agonist/Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists the Same?

- The Role of Tiotropium+Olodaterol Dual Bronchodilator Therapy in the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- The role of tiotropium in the management of asthma

- A Comparison of International Guidelines for Pediatric Asthma Pharmacotherapy