Korean J Orthod.

2024 Mar;54(2):79-88. 10.4041/kjod23.173.

Cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation of mandibular incisor alveolar bone changes for the intrusion arch technique: A retrospective cohort research

- Affiliations

-

- 1Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Zhejiang Provincial Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedical Research of Zhejiang Province, Cancer Center of Zhejiang University, Engineering Research Center of Oral Biomaterials and Devices of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China

- 2Department of Stomatology, Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine Hospital of Linping District, Hangzhou, China

- KMID: 2554365

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4041/kjod23.173

Abstract

Objective

Alveolar bone loss is a common adverse effect of intrusion treatment. Mandibular incisors are prone to dehiscence and fenestrations as they suffer from thinner alveolar bone thickness.

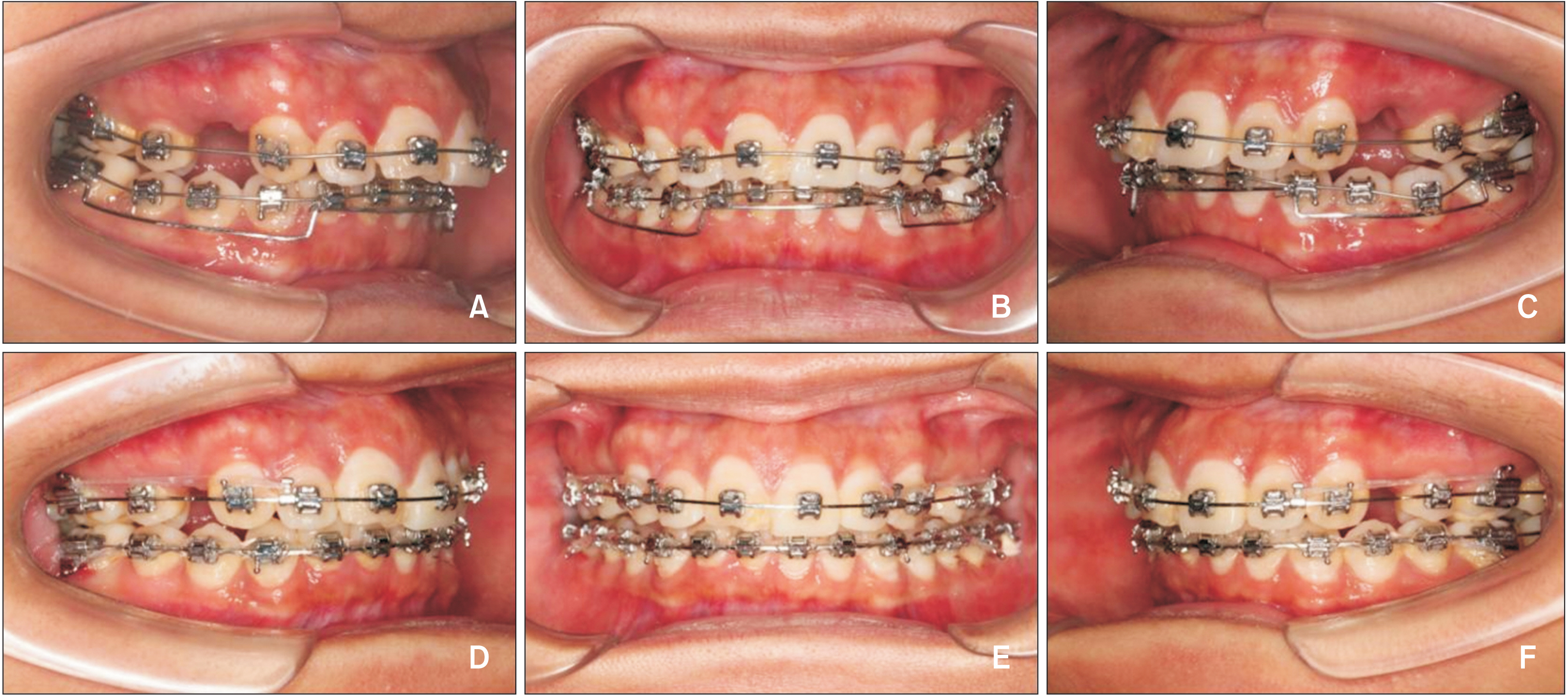

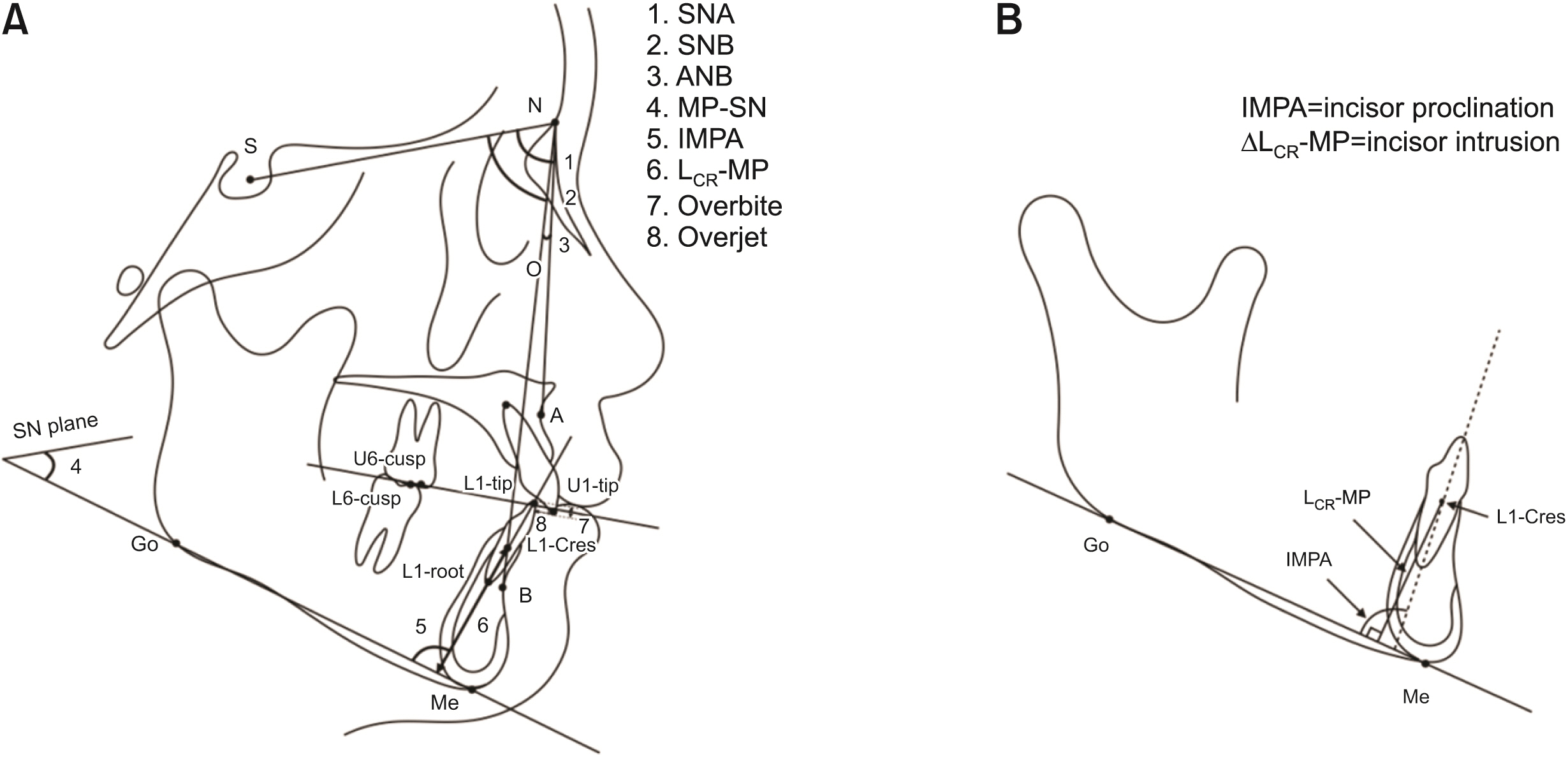

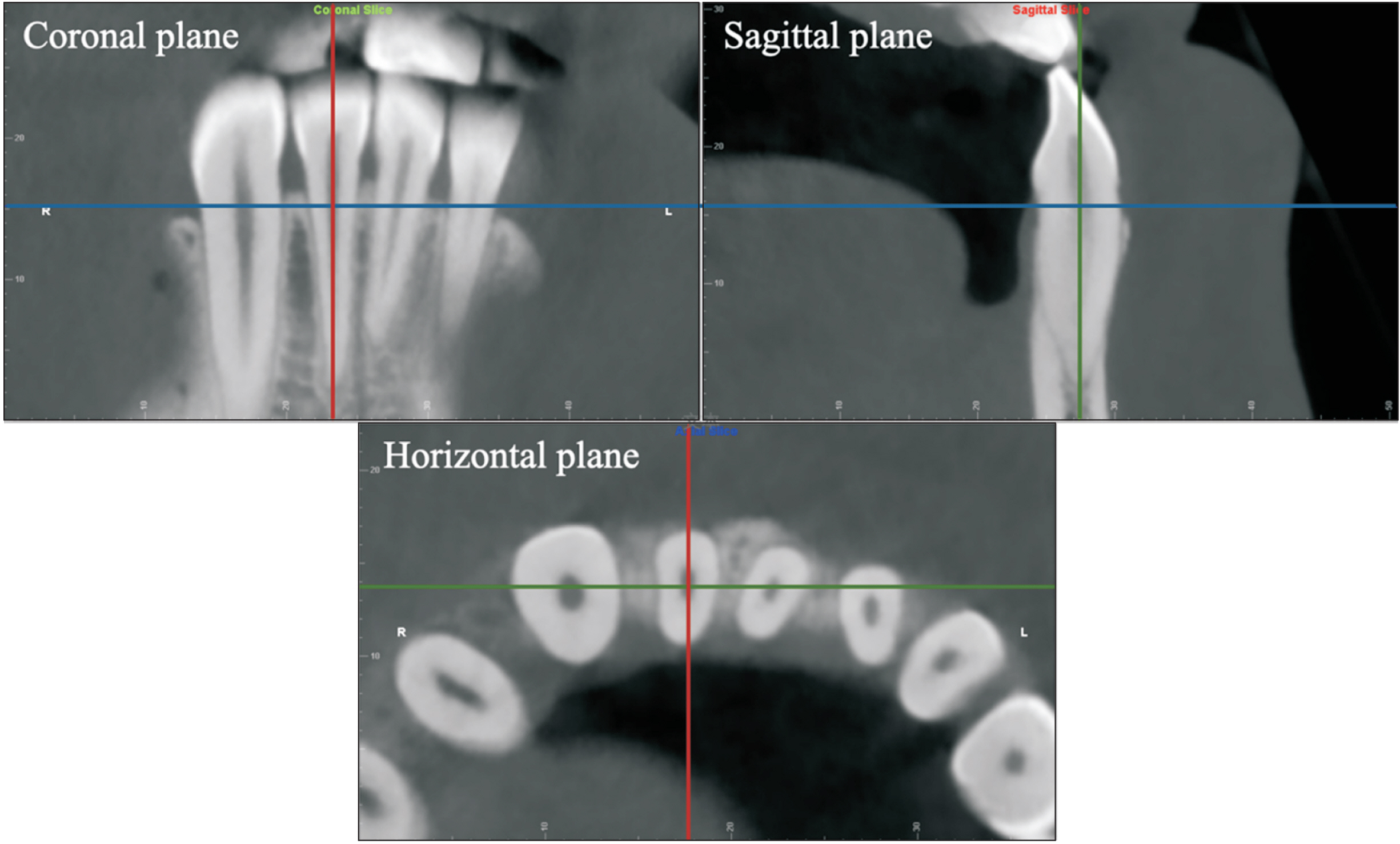

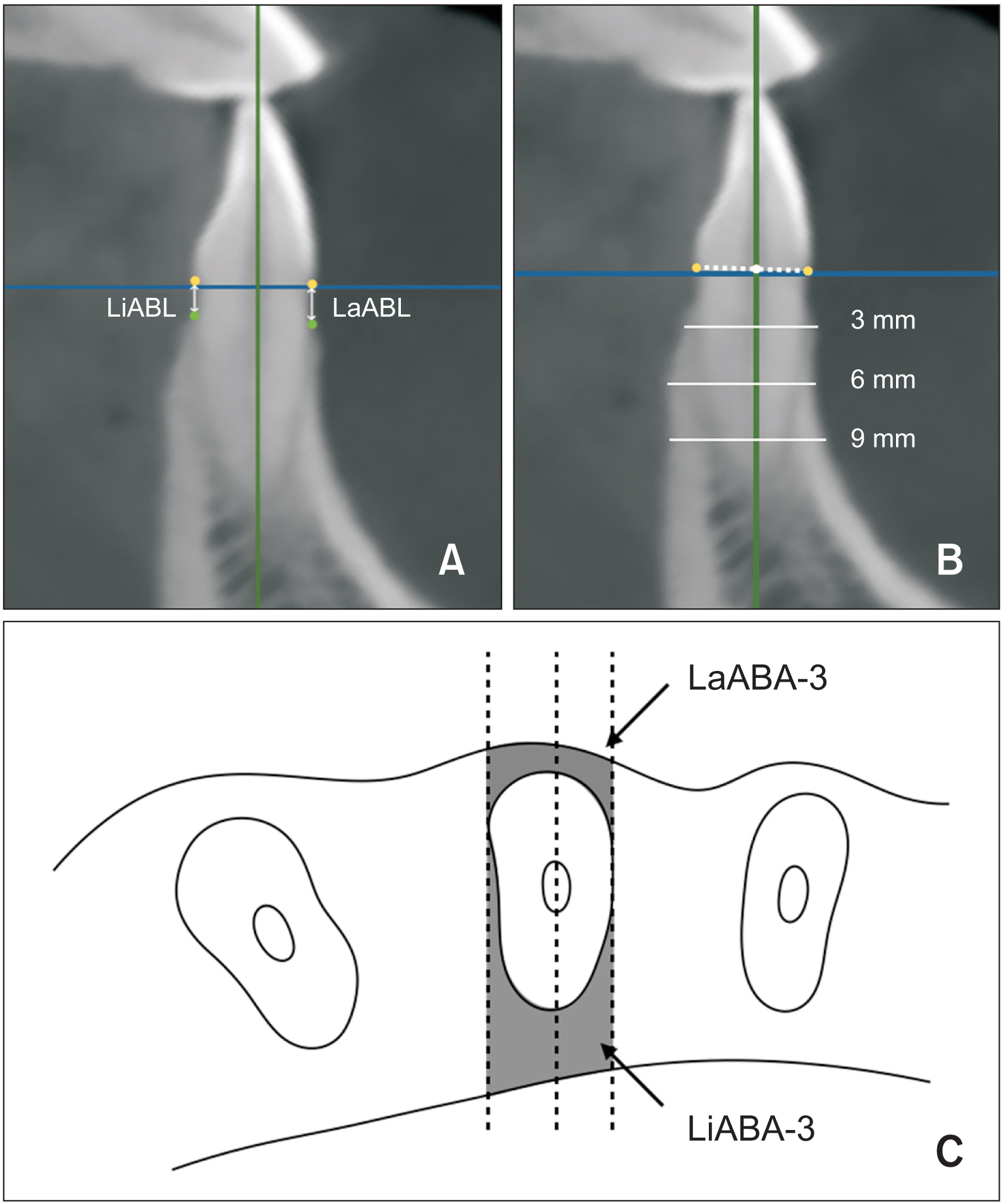

Methods

Thirty skeletal class II patients treated with mandibular intrusion arch therapy were included in this study. Lateral cephalograms and cone-beam computed tomography images were taken before treatment (T1) and immediately after intrusion arch removal (T2) to evaluate the tooth displacement and the alveolar bone changes. Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation was used to identify risk factors of alveolar bone loss during the intrusion treatment.

Results

Deep overbite was successfully corrected (P < 0.05), accompanied by mandibular incisor proclination (P < 0.05). There were no statistically significant change in the true incisor intrusion (P > 0.05). The labial and lingual vertical alveolar bone levels showed a significant decrease (P < 0.05). The alveolar bone is thinning in the labial crestal area and lingual apical area (P < 0.05); accompanied by thickening in the labial apical area (P < 0.05). Proclined incisors, non-extraction treatment, and increased A point-nasion-B point (ANB) degree were positively correlated with alveolar bone loss.

Conclusions

While the mandibular intrusion arch effectively corrected the deep overbite, it did cause some unwanted incisor labial tipping/flaring. During the intrusion treatment, the alveolar bone underwent corresponding changes, which was thinning in the labial crestal area and thickening in the labial apical area vice versa. And increased axis change of incisors, non-extraction treatment, and increased ANB were identified as risk factors for alveolar bone loss in patients with mandibular intrusion therapy.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Antoun JS, Mei L, Gibbs K, Farella M. 2017; Effect of orthodontic treatment on the periodontal tissues. Periodontol 2000. 74:140–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12194. DOI: 10.1111/prd.12194. PMID: 28429487.

Article2. Sonnesen L, Svensson P. 2008; Temporomandibular disorders and psychological status in adult patients with a deep bite. Eur J Orthod. 30:621–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjn044. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjn044. PMID: 18684706.

Article3. Thote AM, Uddanwadiker RV, Sharma K, Shrivastava S. 2016; Optimum force system for intrusion and extrusion of maxillary central incisor in labial and lingual orthodontics. Comput Biol Med. 69:112–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.12.014. DOI: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.12.014. PMID: 26764877.

Article4. Elkholy F, Wulf S, Jäger R, Schmidt F, Lapatki BG. 2023; Mechanical loads exerted by different configurations of Burstone's 3-piece segmented mechanics during a simulated intrusion of the mandibular incisors. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 164:106–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.11.014. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.11.014. PMID: 36934058.

Article5. Alam F, Chauhan AK, Sharma A, Verma S, Raj Y. 2023; Comparative cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation of maxillary incisor intrusion and associated root resorption: intrusion arch vs mini-implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 163:e84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.12.007. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.12.007. PMID: 36635144.

Article6. de Almeida MR, Marçal ASB, Fernandes TMF, Vasconcelos JB, de Almeida RR, Nanda R. 2018; A comparative study of the effect of the intrusion arch and straight wire mechanics on incisor root resorption: a randomized, controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 88:20–6. https://doi.org/10.2319/06417-424R. DOI: 10.2319/06417-424R. PMID: 28985106. PMCID: PMC8315715.

Article7. Kee YJ, Moon HE, Lee KC. 2023; Evaluation of alveolar bone changes around mandibular incisors during surgical orthodontic treatment of patients with mandibular prognathism: surgery-first approach vs conventional orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 163:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.08.028. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.08.028. PMID: 36127191.

Article8. Kalina E, Grzebyta A, Zadurska M. 2022; Bone remodeling during orthodontic movement of lower incisors-narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19:15002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215002. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph192215002. PMID: 36429721. PMCID: PMC9691226.

Article9. Beckmann SH, Kuitert RB, Prahl-Andersen B, Segner D, The RP, Tuinzing DB. 1998; Alveolar and skeletal dimensions associated with lower face height. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 113:498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70260-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0889-5406(98)70260-4. PMID: 9598607.

Article10. Beckmann SH, Kuitert RB, Prahl-Andersen B, Segner D, The RP, Tuinzing DB. 1998; Alveolar and skeletal dimensions associated with overbite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 113:443–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-5406(98)80017-6. DOI: 10.1016/S0889-5406(98)80017-6. PMID: 9563361.

Article11. Sameshima GT, Asgarifar KO. 2001; Assessment of root resorption and root shape: periapical vs panoramic films. Angle Orthod. 71:185–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11407770/.12. Aydoğdu E, Özsoy ÖP. 2011; Effects of mandibular incisor intrusion obtained using a conventional utility arch vs bone anchorage. Angle Orthod. 81:767–75. https://doi.org/10.2319/120610-703.1. DOI: 10.2319/120610-703.1. PMID: 21469970. PMCID: PMC8916171.

Article13. Erkan M, Pikdoken L, Usumez S. 2007; Gingival response to mandibular incisor intrusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 132:143.e9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.10.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.10.015. PMID: 17693359.

Article14. Polat-Özsoy Ö, Arman-Özçırpıcı A, Veziroğlu F, Çetinşahin A. 2011; Comparison of the intrusive effects of miniscrews and utility arches. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 139:526–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.05.040. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.05.040. PMID: 21457864.

Article15. Smith RJ, Burstone CJ. 1984; Mechanics of tooth movement. Am J Orthod. 85:294–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9416(84)90187-8. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90187-8. PMID: 6585147.

Article16. Christensen JR, Fields H, Sheats RD. Nowak AJ, Christensen JR, Mabry TR, Townsend JA, Wells MH, editors. 2019. Treatment planning and management of orthodontic problems. Pediatric dentistry. Elsevier;Philadelphia: p. 512–53. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-60826-8.00036-5.17. Vela-Hernández A, Gutiérrez-Zubeldia L, López-García R, García-Sanz V, Paredes-Gallardo V, Gandía-Franco JL, et al. 2020; One versus two anterior miniscrews for correcting upper incisor overbite and angulation: a retrospective comparative study. Prog Orthod. 21:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-020-00336-2. DOI: 10.1186/s40510-020-00336-2. PMID: 32893322. PMCID: PMC7475152. PMID: 33c3352cffad43929b52274bff96ed78.

Article18. Ng J, Major PW, Heo G, Flores-Mir C. 2005; True incisor intrusion attained during orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 128:212–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.04.025. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.04.025. PMID: 16102407.

Article19. Shakti P, Ani GS, Peter E, Haider K, Kumar J. 2021; Maxillary incisor intrusion using two conventional intrusion arches and mini implants: a prospective study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 22:907–13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34753843/. DOI: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3136. PMID: 34753843.

Article20. Kale Varlık S, Onur Alpakan Ö, Türköz Ç. 2013; Deepbite correction with incisor intrusion in adults: a long-term cephalometric study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 144:414–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.014. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.014. PMID: 23992814.

Article21. Atik E, Gorucu-Coskuner H, Akarsu-Guven B, Taner T. 2018; Evaluation of changes in the maxillary alveolar bone after incisor intrusion. Korean J Orthod. 48:367–76. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2018.48.6.367. DOI: 10.4041/kjod.2018.48.6.367. PMID: 30450329. PMCID: PMC6234111.

Article22. Bayani S, Heravi F, Radvar M, Anbiaee N, Madani AS. 2015; Periodontal changes following molar intrusion with miniscrews. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 12:379–85. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-3327.161462. DOI: 10.4103/1735-3327.161462. PMID: 26288629. PMCID: PMC4533198. PMID: 0a618b5a98de4bf39ffe06a5fcb897fd.

Article23. Hernández-Sayago E, Espinar-Escalona E, Barrera-Mora JM, Ruiz-Navarro MB, Llamas-Carreras JM, Solano-Reina E. 2013; Lower incisor position in different malocclusions and facial patterns. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 18:e343–50. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.18434. DOI: 10.4317/medoral.18434. PMID: 23229262. PMCID: PMC3613890.

Article24. Corelius M, Linder-Aronson S. 1976; The relationship between lower incisor inclination and various reference lines. Angle Orthod. 46:111–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1064340/.25. Molina-Berlanga N, Llopis-Perez J, Flores-Mir C, Puigdollers A. 2013; Lower incisor dentoalveolar compensation and symphysis dimensions among Class I and III malocclusion patients with different facial vertical skeletal patterns. Angle Orthod. 83:948–55. https://doi.org/10.2319/011913-48.1. DOI: 10.2319/011913-48.1. PMID: 23758599. PMCID: PMC8722832.

Article26. Rozzi M, Mucedero M, Pezzuto C, Cozza P. 2017; Leveling the curve of Spee with continuous archwire appliances in different vertical skeletal patterns: a retrospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 151:758–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.023. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.023. PMID: 28364900.

Article27. Yodthong N, Charoemratrote C, Leethanakul C. 2013; Factors related to alveolar bone thickness during upper incisor retraction. Angle Orthod. 83:394–401. https://doi.org/10.2319/062912-534.1. DOI: 10.2319/062912-534.1. PMID: 23043245. PMCID: PMC8763077.

Article28. Zeitounlouian TS, Zeno KG, Brad BA, Haddad RA. 2021; Three-dimensional evaluation of the effects of injectable platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF) on alveolar bone and root length during orthodontic treatment: a randomized split mouth trial. BMC Oral Health. 21:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01456-9. DOI: 10.1186/s12903-021-01456-9. PMID: 33653326. PMCID: PMC7971145. PMID: b6d0a221c58c43a9962c172673cf8714.

Article29. Chung DH, Park YG, Kim KW, Cha KS. 2011; Factors affecting orthodontically induced root resorption of maxillary central incisors in the Korean population. Korean J Orthod. 41:174–83. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2011.41.3.174. DOI: 10.4041/kjod.2011.41.3.174.

Article30. Irvine R, Power S, McDonald F. 2004; The effectiveness of laceback ligatures: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Orthod. 31:303–11. discussion 300https://doi.org/10.1179/146531204225020606. DOI: 10.1179/146531204225020606. PMID: 15608345.

Article31. Schwertner A, de Almeida RR, de Almeida-Pedrin RR, Fernandes TMF, Oltramari P, de Almeida MR. 2020; A prospective clinical trial of the effects produced by the Connecticut intrusion arch on the maxillary dental arch. Angle Orthod. 90:500–6. https://doi.org/10.2319/102219-666.1. DOI: 10.2319/102219-666.1. PMID: 33378499. PMCID: PMC8028463.

Article32. Coşkun İ, Kaya B. 2019; Relationship between alveolar bone thickness, tooth root morphology, and sagittal skeletal pattern: a cone beam computed tomography study. J Orofac Orthop. 80:144–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-019-00175-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00056-019-00175-9. PMID: 30980091.

Article33. Gracco A, Luca L, Bongiorno MC, Siciliani G. 2010; Computed tomography evaluation of mandibular incisor bony support in untreated patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 138:179–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.030. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.030. PMID: 20691359.

Article34. Hoang N, Nelson G, Hatcher D, Oberoi S. 2016; Evaluation of mandibular anterior alveolus in different skeletal patterns. Prog Orthod. 17:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-016-0135-z. DOI: 10.1186/s40510-016-0135-z. PMID: 27439994. PMCID: PMC4954804. PMID: d0d6d5fd9c7a49868a10bdbd4d7b32d1.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Evaluation of changes in the maxillary alveolar bone after incisor intrusion

- Reproducibility of cone-beam computed tomographic measurements of bone plates and the interdental septum in the anterior mandible

- Three-dimensional evaluation of maxillary anterior alveolar bone for optimal placement of miniscrew implants

- Alveolar bone thickness and fenestration of incisors in untreated Korean patients with skeletal class III malocclusion: A retrospective 3-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography study

- Three-dimensional assessment of the temporomandibular joint and mandibular dimensions after early correction of the maxillary arch form in patients with Class II division 1 or division 2 malocclusion