Three-dimensional evaluation of maxillary anterior alveolar bone for optimal placement of miniscrew implants

- Affiliations

-

- 1Private Practice, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Orthodontics, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. yumichael@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2273427

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2014.44.2.54

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to propose clinical guidelines for placing miniscrew implants using the results obtained from 3-dimensional analysis of maxillary anterior interdental alveolar bone by cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).

METHODS

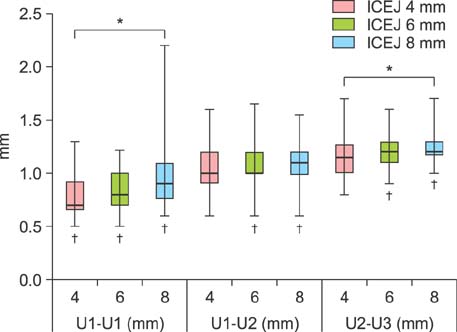

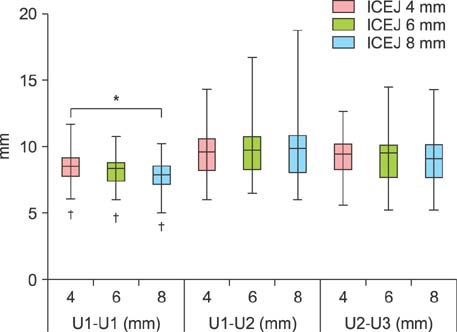

By using CBCT data from 52 adult patients (17 men and 35 women; mean age, 27.9 years), alveolar bone were measured in 3 regions: between the maxillary central incisors (U1-U1), between the maxillary central incisor and maxillary lateral incisor (U1-U2), and between the maxillary lateral incisor and the canine (U2-U3). Cortical bone thickness, labio-palatal thickness, and interdental root distance were measured at 4 mm, 6 mm, and 8 mm apical to the interdental cementoenamel junction (ICEJ).

RESULTS

The cortical bone thickness significantly increased from the U1-U1 region to the U2-U3 region (p < 0.05). The labio-palatal thickness was significantly less in the U1-U1 region (p < 0.05), and the interdental root distance was significantly less in the U1-U2 region (p < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study suggest that the interdental root regions U2-U3 and U1-U1 are the best sites for placing miniscrew implants into maxillary anterior alveolar bone.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 5 articles

-

Scar formation and revision after the removal of orthodontic miniscrews

Yoon Jeong Choi, Dong-Won Lee, Kyung-Ho Kim, Chooryung J. Chung

Korean J Orthod. 2015;45(3):146-150. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2015.45.3.146.Comparison of cone-beam computed tomography cephalometric measurements using a midsagittal projection and conventional two-dimensional cephalometric measurements

Pil-Kyo Jung, Gung-Chol Lee, Cheol-Hyun Moon

Korean J Orthod. 2015;45(6):282-288. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2015.45.6.282.Miniscrews versus surgical archwires for intermaxillary fixation in adults after orthognathic surgery

Sieun Son, Seong Sik Kim, Woo-Sung Son, Yong-Il Kim, Yong-Deok Kim, Sang-Hun Shin

Korean J Orthod. 2015;45(1):3-12. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2015.45.1.3.The effects of alveolar bone loss and miniscrew position on initial tooth displacement during intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth: Finite element analysis

Sun-Mi Cho, Sung-Hwan Choi, Sang-Jin Sung, Hyung-Seog Yu, Chung-Ju Hwang

Korean J Orthod. 2016;46(5):310-322. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2016.46.5.310.Effect of slow forced eruption on the vertical levels of the interproximal bone and papilla and the width of the alveolar ridge

Eun-Young Kwon, Ju-Youn Lee, Jeomil Choi

Korean J Orthod. 2016;46(6):379-385. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2016.46.6.379.

Reference

-

1. Silberberg N, Goldstein M, Smidt A. Excessive gingival display-etiology, diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Quintessence Int. 2009; 40:809–818.2. Jung MH. Age, extraction rate and jaw surgery rate in Korean orthodontic clinics and small dental hospitals. Korean J Orthod. 2012; 42:80–86.

Article3. Im DH, Kim TW, Nahm DS, Chang YI. Current trends in orthodontic patients in Seoul National University Dental Hospital. Korean J Orthod. 2003; 33:63–72.4. Sarver DM. Principles of cosmetic dentistry in orthodontics: Part 1. Shape and proportionality of anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 126:749–753.

Article5. Sarver DM, Yanosky M. Principles of cosmetic dentistry in orthodontics: part 2. Soft tissue laser technology and cosmetic gingival contouring. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005; 127:85–90.

Article6. Monaco A, Streni O, Marci MC, Marzo G, Gatto R, Giannoni M. Gummy smile: clinical parameters useful for diagnosis and therapeutical approach. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004; 29:19–25.

Article7. Levine RA, McGuire M. The diagnosis and treatment of the gummy smile. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1997; 18:757–762. 764quiz 766.8. Ohnishi H, Yagi T, Yasuda Y, Takada K. A miniimplant for orthodontic anchorage in a deep overbite case. Angle Orthod. 2005; 75:444–452.9. Deguchi T, Murakami T, Kuroda S, Yabuuchi T, Kamioka H, Takano-Yamamoto T. Comparison of the intrusion effects on the maxillary incisors between implant anchorage and J-hook headgear. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 133:654–660.

Article10. Lin JC, Liou EJ, Bowman SJ. Simultaneous reduction in vertical dimension and gummy smile using miniscrew anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2010; 44:157–170.11. Saxena R, Kumar PS, Upadhyay M, Naik V. A clinical evaluation of orthodontic mini-implants as intraoral anchorage for the intrusion of maxillary anterior teeth. World J Orthod. 2010; 11:346–351.12. Polat-Özsoy Ö, Arman-Özçırpıcı A, Veziroğlu F, Çetinşahin A. Comparison of the intrusive effects of miniscrews and utility arches. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:526–532.

Article13. Senışık NE, Türkkahraman H. Treatment effects of intrusion arches and mini-implant systems in deepbite patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012; 141:723–733.

Article14. Kaku M, Kojima S, Sumi H, et al. Gummy smile and facial profile correction using miniscrew anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2012; 82:170–177.

Article15. Schnelle MA, Beck FM, Jaynes RM, Huja SS. A radiographic evaluation of the availability of bone for placement of miniscrews. Angle Orthod. 2004; 74:832–837.16. Lee KJ, Joo E, Kim KD, Lee JS, Park YC, Yu HS. Computed tomographic analysis of tooth-bearing alveolar bone for orthodontic miniscrew placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135:486–494.

Article17. Gahleitner A, Podesser B, Schick S, Watzek G, Imhof H. Dental CT and orthodontic implants: imaging technique and assessment of available bone volume in the hard palate. Eur J Radiol. 2004; 51:257–262.

Article18. Deguchi T, Nasu M, Murakami K, Yabuuchi T, Kamioka H, Takano-Yamamoto T. Quantitative evaluation of cortical bone thickness with computed tomographic scanning for orthodontic implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 129:721.e7–721.e12.

Article19. Kim JH, Park YC. Evaluation of mandibular cortical bone thickness for placement of temporary anchorage devices (TADs). Korean J Orthod. 2012; 42:110–117.

Article20. Farnsworth D, Rossouw PE, Ceen RF, Buschang PH. Cortical bone thickness at common miniscrew implant placement sites. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:495–503.

Article21. Albrektsson T, Brånemark PI, Hansson HA, Lindström J. Osseointegrated titanium implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981; 52:155–170.

Article22. Roberts WE, Smith RK, Zilberman Y, Mozsary PG, Smith RS. Osseous adaptation to continuous loading of rigid endosseous implants. Am J Orthod. 1984; 86:95–111.

Article23. Costa A, Raffainl M, Melsen B. Miniscrews as orthodontic anchorage: a preliminary report. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:201–209.24. Park HS, Jeong SH, Kwon OW. Factors affecting the clinical success of screw implants used as orthodontic anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130:18–25.

Article25. Park J, Cho HJ. Three-dimensional evaluation of interradicular spaces and cortical bone thickness for the placement and initial stability of microimplants in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 136:314.e1–314.e12. discussion 314-5.

Article26. Santiago RC, de Paula FO, Fraga MR, Picorelli Assis NM, Vitral RW. Correlation between miniscrew stability and bone mineral density in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 136:243–250.

Article27. Frost HM. Bone "mass" and the "mechanostat": a proposal. Anat Rec. 1987; 219:1–9.

Article28. Frost HM. Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 1. Redefining Wolff's law: the bone modeling problem. Anat Rec. 1990; 226:403–413.

Article29. Frost HM. Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 2. Redefining Wolff's law: the remodeling problem. Anat Rec. 1990; 226:414–422.

Article30. Frost HM. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an overview for clinicians. Angle Orthod. 1994; 64:175–188.31. Meredith N, Alleyne D, Cawley P. Quantitative determination of the stability of the implant-tissue interface using resonance frequency analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996; 7:261–267.

Article32. Meredith N. A review of nondestructive test methods and their application to measure the stability and osseointegration of bone anchored endosseous implants. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1998; 26:275–291.

Article33. Wilmes B, Rademacher C, Olthoff G, Drescher D. Parameters affecting primary stability of orthodontic mini-implants. J Orofac Orthop. 2006; 67:162–174.

Article34. Miyamoto I, Tsuboi Y, Wada E, Suwa H, Iizuka T. Influence of cortical bone thickness and implant length on implant stability at the time of surgery-clinical, prospective, biomechanical, and imaging study. Bone. 2005; 37:776–780.

Article35. Burstone CR. Deep overbite correction by intrusion. Am J Orthod. 1977; 72:1–22.

Article36. Weiland FJ, Bantleon HP, Droschl H. Evaluation of continuous arch and segmented arch leveling techniques in adult patients--a clinical study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996; 110:647–652.

Article37. Davies JE. Understanding peri-implant endosseous healing. J Dent Educ. 2003; 67:932–949.

Article38. Moon CH, Lee DG, Lee HS, Im JS, Baek SH. Factors associated with the success rate of orthodontic miniscrews placed in the upper and lower posterior buccal region. Angle Orthod. 2008; 78:101–106.

Article39. Kuroda S, Sugawara Y, Deguchi T, Kyung HM, Takano-Yamamoto T. Clinical use of miniscrew implants as orthodontic anchorage: success rates and postoperative discomfort. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007; 131:9–15.

Article40. Poggio PM, Incorvati C, Velo S, Carano A. "Safe zones": a guide for miniscrew positioning in the maxillary and mandibular arch. Angle Orthod. 2006; 76:191–197.41. Janson G, Gigliotti MP, Estelita S, Chiqueto K. Influence of miniscrew dental root proximity on its degree of late stability. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 42:527–534.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Angulation between Long Axis of Anterior Teeth and Alveolar Process, and Thickness of Alveolar Bone

- The effects of alveolar bone loss and miniscrew position on initial tooth displacement during intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth: Finite element analysis

- Alveolar Ridge Preservation in the Severely Damaged Sockets of the Anterior Maxilla Followed by Delayed Implant Placement

- Survival rate of Astra Tech implants with maxillary sinus lift

- Alveolar Bone Distraction Osteogenesis at Maxillary Anterior Region for Forward-Downward Movement