Int J Stem Cells.

2020 Nov;13(3):377-385. 10.15283/ijsc20024.

Isolation and Characterization of Human Suture Mesenchymal Stem Cells In Vitro

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Plastic Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- KMID: 2508911

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc20024

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

Cranial sutures play a critical role in adjustment of skull development and brain growth. Premature fusion of cranial sutures leads to craniosynostosis. The aim of the current study was to culture and characterize human cranial suture mesenchymal cells in vitro.

Methods

The residual skull tissues, containing synostosed or contralateral suture from three boys with right coronal suture synostosis, were used to isolate the suture mesenchymal cells. Then, flow cytometry and multilineage differentiation were performed to identify the typical mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) properties. Finally, we used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect the mRNA expression of osteogenesis and stemness related genes.

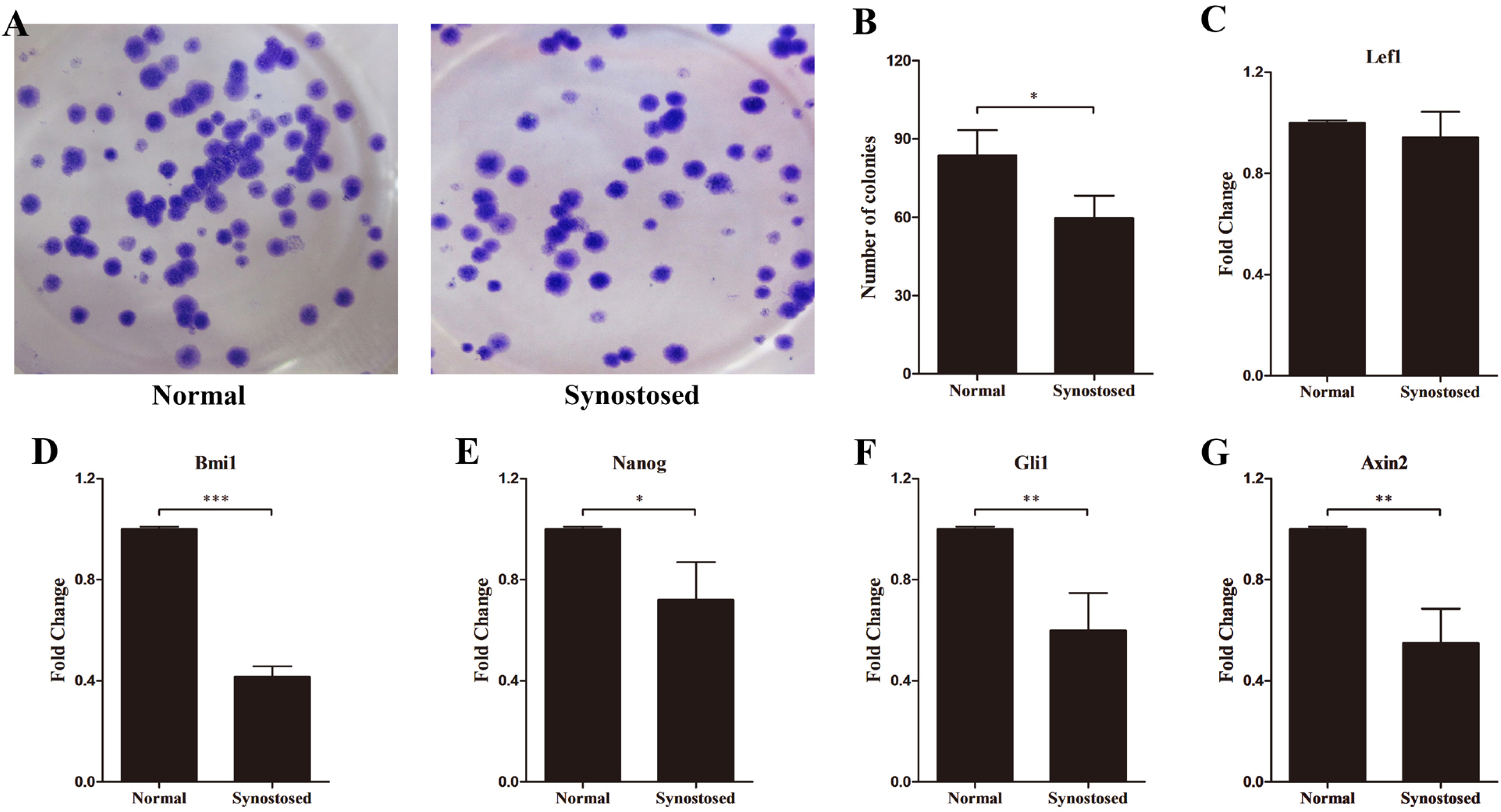

Results

After 3 to 5 days in culture, the cells migrated from the tissue explants and proliferated parallelly or spirally. These cells expressed typical MSC markers, CD73, CD90, CD105, and could give rises to osteocytes, adipocytes and chondrocytes. RT-PCR showed relatively higher levels of Runx2, osteocalcin and FGF2 in the fused suture MSCs than in the normal cells. However, BMP3, the only protein of BMP family that inhibits osteogenesis, reduced in synostosed suture derived cells. The expression of effector genes remaining cell stemness, including Bmi1, Gli1 and Axin2, decreased in the cells migrated from the affected cranial sutures.

Conclusions

The MSCs from prematurely occlusive sutures overexpressed osteogenic related genes and down-regulated stemness-related genes, which may further accelerate the osteogenic differentiation and suppress the self-renewal of stem cells leading to craniosynostosis.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Slater BJ, Lenton KA, Kwan MD, Gupta DM, Wan DC, Longaker MT. 2008; Cranial sutures: a brief review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 121:170e–178e. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000304441.99483.97. PMID: 18349596.

Article2. Twigg SR, Wilkie AO. 2015; A genetic-pathophysiological framework for craniosynostosis. Am J Hum Genet. 97:359–377. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.006. PMID: 26340332. PMCID: PMC4564941.

Article3. Wilkie AO. 2000; Epidemiology and genetics of craniosynostosis. Am J Med Genet. 90:82–84. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000103)90:1<82::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID: 10602123.

Article4. Forrest CR, Hopper RA. 2013; Craniofacial syndromes and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 131:86e–109e. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318272c12b. PMID: 23271559.

Article5. Kirmi O, Lo SJ, Johnson D, Anslow P. 2009; Craniosynostosis: a radiological and surgical perspective. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 30:492–512. DOI: 10.1053/j.sult.2009.08.002. PMID: 20099636.

Article6. Hankinson TC, Fontana EJ, Anderson RC, Feldstein NA. 2010; Surgical treatment of single-suture craniosynostosis: an argument for quantitative methods to evaluate cosmetic outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 6:193–197. DOI: 10.3171/2010.5.PEDS09313. PMID: 20672943.

Article7. Wan DC, Kwan MD, Lorenz HP, Longaker MT. 2008; Current treatment of craniosynostosis and future therapeutic direc-tions. Front Oral Biol. 12:209–230. DOI: 10.1159/000115043. PMID: 18391503.

Article8. Sahar DE, Longaker MT, Quarto N. 2005; Sox9 neural crest determinant gene controls patterning and closure of the posterior frontal cranial suture. Dev Biol. 280:344–361. DOI: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.022. PMID: 15882577.

Article9. Xu Y, Malladi P, Chiou M, Longaker MT. 2007; Isolation and characterization of posterofrontal/sagittal suture mesenchy-mal cells in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 119:819–829. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000255540.91987.a0. PMID: 17312483.

Article10. Nacamuli RP, Fong KD, Lenton KA, Song HM, Fang TD, Salim A, Longaker MT. 2005; Expression and possible mechanisms of regulation of BMP3 in rat cranial sutures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 116:1353–1362. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000182223.85978.34. PMID: 16217479.

Article11. Zhao H, Feng J, Ho TV, Grimes W, Urata M, Chai Y. 2015; The suture provides a niche for mesenchymal stem cells of craniofacial bones. Nat Cell Biol. 17:386–396. DOI: 10.1038/ncb3139. PMID: 25799059. PMCID: PMC4380556.

Article12. Maruyama T, Jeong J, Sheu TJ, Hsu W. 2016; Stem cells of the suture mesenchyme in craniofacial bone development, repair and regeneration. Nat Commun. 7:10526. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10526. PMID: 26830436. PMCID: PMC4740445.

Article13. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001; Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. DOI: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. PMID: 11846609.

Article14. Ni QF, Tian Y, Kong LL, Lu YT, Ding WZ, Kong LB. 2014; Latexin exhibits tumor suppressor potential in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 31:1364–1372. DOI: 10.3892/or.2014.2966. PMID: 24399246.

Article15. Lemonnier J, Haÿ E, Delannoy P, Lomri A, Modrowski D, Caverzasio J, Marie PJ. 2001; Role of N-cadherin and protein kinase C in osteoblast gene activation induced by the S252W fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutation in Apert cra-niosynostosis. J Bone Miner Res. 16:832–845. DOI: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.832. PMID: 11341328.

Article16. Buchanan EP, Xue AS, Hollier LH Jr. 2014; Craniofacial synd-romes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 134:128e–153e. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000308. PMID: 25028828.

Article17. Sauvageau M, Sauvageau G. 2010; Polycomb group proteins: multi-faceted regulators of somatic stem cells and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 7:299–313. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.002. PMID: 20804967. PMCID: PMC4959883.

Article18. Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. 2001; Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 414:105–111. DOI: 10.1038/35102167. PMID: 11689955.

Article19. Otto AW. 1830. Lehrbuch der pathologischen Anatomie des Menschen und der Thiere/1. Rücker;Berlin: DOI: 10.1097/00000441-183108150-00023.20. Jiang T, Ge S, Shim YH, Zhang C, Cao D. 2015; Bone morphogenetic protein is required for fibroblast growth factor 2-dependent later-stage osteoblastic differentiation in cranial suture cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8:2946–2954. PMID: 26045803. PMCID: PMC4440112.21. Rice DP. 2008; Developmental anatomy of craniofacial sutures. Front Oral Biol. 12:1–21. DOI: 10.1159/000115028. PMID: 18391492.

Article22. Heller JB, Gabbay JS, Wasson K, Mitchell S, Heller MM, Zuk P, Bradley JP. 2007; Cranial suture response to stress: expre-ssion patterns of Noggin and Runx2. Plast Reconstr Surg. 119:2037–2045. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000260589.75706.19. PMID: 17519698.

Article23. Park J, Park OJ, Yoon WJ, Kim HJ, Choi KY, Cho TJ, Ryoo HM. 2012; Functional characterization of a novel FGFR2 mutation, E731K, in craniosynostosis. J Cell Biochem. 113:457–464. DOI: 10.1002/jcb.23368. PMID: 21928350.

Article24. McGee-Lawrence ME, Li X, Bledsoe KL, Wu H, Hawse JR, Subramaniam M, Razidlo DF, Stensgard BA, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Hsu W, Westendorf JJ. 2013; Runx2 protein represses Axin2 expression in osteoblasts and is required for craniosynostosis in Axin2-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 288:5291–5302. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.414995. PMID: 23300083. PMCID: PMC3581413.

Article25. Delezoide AL, Benoist-Lasselin C, Legeai-Mallet L, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, Vekemans M, Bonaventure J. 1998; Spatio-temporal expression of FGFR 1, 2 and 3 genes during human embryo-fetal ossification. Mech Dev. 77:19–30. DOI: 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00133-6. PMID: 9784595.

Article26. Greenwald JA, Mehrara BJ, Spector JA, Warren SM, Fagenholz PJ, Smith LE, Bouletreau PJ, Crisera FE, Ueno H, Longaker MT. 2001; In vivo modulation of FGF biological activity alters cranial suture fate. Am J Pathol. 158:441–452. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63987-9. PMID: 11159182. PMCID: PMC1850306.

Article27. Jung Y, Nolta JA. 2016; BMI1 regulation of self-renewal and multipotency in human mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 11:131–140. DOI: 10.2174/1574888X1102160107171432. PMID: 26763885.

Article28. Alhadlaq A, Mao JJ. 2004; Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and therapeutics. Stem Cells Dev. 13:436–448. DOI: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.436. PMID: 15345137.

Article29. Bhattacharya R, Mustafi SB, Street M, Dey A, Dwivedi SK. 2015; Bmi-1: at the crossroads of physiological and pathological biology. Genes Dis. 2:225–239. DOI: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.04.001. PMID: 26448339. PMCID: PMC4593320.

Article30. van der Lugt NM, Domen J, Linders K, van Roon M, Robanus-Maandag E, te Riele H, van der Valk M, Deschamps J, Sofroniew M, van Lohuizen M, Berns A. 1994; Posterior transformation, neurological abnormalities, and severe hematopoietic defects in mice with a targeted deletion of the bmi-1 proto-oncogene. Genes Dev. 8:757–769. DOI: 10.1101/gad.8.7.757. PMID: 7926765.

Article31. Biehs B, Hu JK, Strauli NB, Sangiorgi E, Jung H, Heber RP, Ho S, Goodwin AF, Dasen JS, Capecchi MR, Klein OD. 2013; BMI1 represses Ink4a/Arf and Hox genes to regulate stem cells in the rodent incisor. Nat Cell Biol. 15:846–852. DOI: 10.1038/ncb2766. PMID: 23728424. PMCID: PMC3735916.

Article32. Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M, Yamanaka S. 2003; The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 113:631–642. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00393-3. PMID: 12787504.

Article33. Xie X, Piao L, Cavey GS, Old M, Teknos TN, Mapp AK, Pan Q. 2014; Phosphorylation of Nanog is essential to regulate Bmi1 and promote tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 33:2040–2052. DOI: 10.1038/onc.2013.173. PMID: 23708658. PMCID: PMC3912208.

Article34. Maruyama T, Mirando AJ, Deng CX, Hsu W. 2010; The balance of WNT and FGF signaling influences mesenchymal stem cell fate during skeletal development. Sci Signal. 3:ra40. DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2000727. PMID: 20501936. PMCID: PMC2902546.

Article35. Yu HM, Jerchow B, Sheu TJ, Liu B, Costantini F, Puzas JE, Birchmeier W, Hsu W. 2005; The role of Axin2 in calvarial morphogenesis and craniosynostosis. Development. 132:1995–2005. DOI: 10.1242/dev.01786. PMID: 15790973. PMCID: PMC1828115.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Concise Review: Differentiation of Human Adult Stem Cells Into Hepatocyte-like Cells In vitro

- Adipose Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- In vitro neuronal and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord blood

- A Mini Overview of Isolation, Characterization and Application of Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells

- Comparative Evaluation for Potential Differentiation of Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Endothelial-Like Cells