Int J Stem Cells.

2020 Mar;13(1):151-162. 10.15283/ijsc19004.

Hyaluronan Induces a Mitochondrial Functional Switch in Fast-Proliferating Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- Affiliations

-

- 1Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies, Panama, Panama

- 2Department of Biotechnology and Bioindustry Sciences, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

- 3Department of Medicine, Mackay Medical College, New Taipei City, Taiwan

- 4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

- 6Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

- 7Research Center of Excellence in Regenerative Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

- 8International Research Center of Wound Repair and Regeneration, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

- KMID: 2500574

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc19004

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

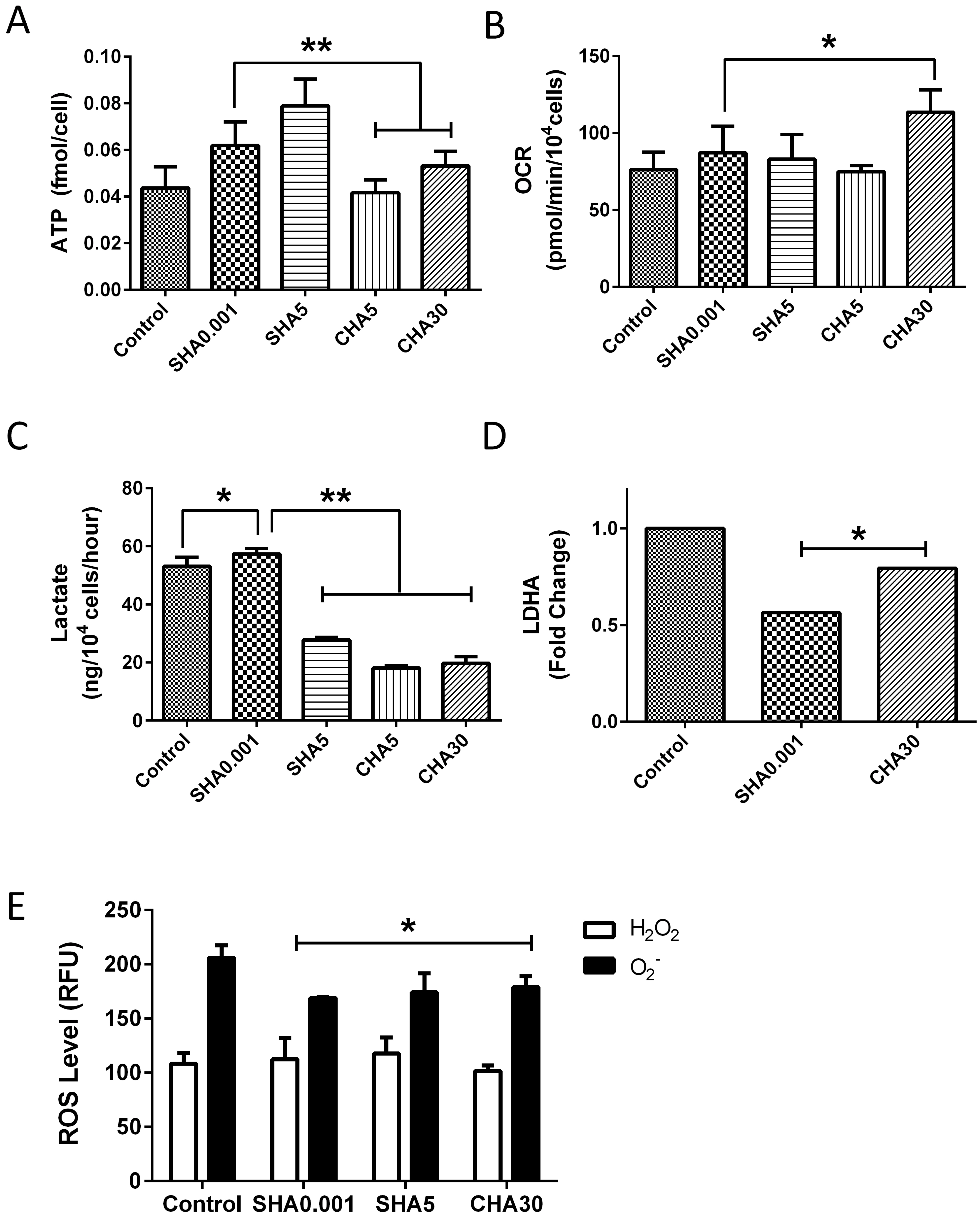

Hyaluronan preserves the proliferation and differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Supplementation of low-concentration hyaluronan (SHA) in stem cells culture medium increases its proliferative rate, whereas coated-surface hyaluronan (CHA) maintains cells in a slow-proliferating mode. We have previously demonstrated that in CHA, the metabolic proliferative state of stem cells was influenced by upregulating mitochondrial biogenesis and function. However, the effect of SHA on stem cells’ energetic status remains unknown. In this study, we demonstrate the effect that low-concentration SHA at 0.001 mg/ml (SHA0.001) and high-concentration SHA at 5 mg/ml (SHA5) exert on stem cells’ mitochondrial function compared with CHA and noncoated tissue culture surface (control).

Methods and Results

Fast-proliferating human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells (PDMSCs) cultured on SHA0.001 exhibited reduced mitochondrial mass, lower mitochondrial DNA copy number, and lower oxygen consumption rate compared with slow-proliferating PDMSCs cultured on CHA at 5.0 (CHA5) or 30 μg/cm2 (CHA30). The reduced mitochondrial biogenesis observed in SHA0.001 was accompanied by a 2-fold increased ATP content and lactate production, suggesting that hyaluronan-induced fast-proliferating PDMSCs may rely less on mitochondrial function as an energy source and induce a mitochondrial functional switch to glycolysis.

Conclusions

PDMSCs cultured on both CHA and SHA exhibited a reduction in reactive oxygen species levels. The results from this study clarify our understandings on the effect of hyaluronan on stem cells and provide important insights into the effect of distinct supplementation methods used during cell therapies.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Wong TY, Chang CH, Yu CH, Huang LLH. 2017; Hyaluronan keeps mesenchymal stem cells quiescent and maintains the differentiation potential over time. Aging Cell. 16:451–460. DOI: 10.1111/acel.12567. PMID: 28474484. PMCID: PMC5418204.

Article2. Chen PY, Huang LL, Hsieh HJ. 2007; Hyaluronan preserves the proliferation and differentiation potentials of long-term cultured murine adipose-derived stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 360:1–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.211. PMID: 17586465.

Article3. Solis MA, Wei YH, Chang CH, Yu CH, Kuo PL, Huang LL. 2016; Hyaluronan upregulates mitochondrial biogenesis and reduces adenoside triphosphate production for efficient mitochondrial function in slow-proliferating human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 34:2512–2524. DOI: 10.1002/stem.2404. PMID: 27354288.

Article4. Alessio N, Stellavato A, Squillaro T, Del Gaudio S, Di Bernardo G, Peluso G, De Rosa M, Schiraldi C, Galderisi U. 2018; Hybrid complexes of high and low molecular weight hyaluronan delay in vitro replicative senescence of mesenchymal stromal cells: a pilot study for future therapeutic application. Aging (Albany NY). 10:1575–1585. DOI: 10.18632/aging.101493. PMID: 30001217. PMCID: PMC6075440.

Article5. Chanmee T, Ontong P, Izumikawa T, Higashide M, Mochizuki N, Chokchaitaweesuk C, Khansai M, Nakajima K, Kakizaki I, Kongtawelert P, Taniguchi N, Itano N. 2016; Hyaluronan production regulates metabolic and cancer stem-like properties of breast cancer cells via hexosamine biosynthetic pathway-coupled HIF-1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 291:24105–24120. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M116.751263. PMID: 27758869. PMCID: PMC5104936.

Article6. Lambricht L, De Berdt P, Vanacker J, Leprince J, Diogenes A, Goldansaz H, Bouzin C, Préat V, Dupont-Gillain C, des Rieux A. 2014; The type and composition of alginate and hyaluronic-based hydrogels influence the viability of stem cells of the apical papilla. Dent Mater. 30:e349–e361. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.08.369. PMID: 25182372.

Article7. Xu X, Duan S, Yi F, Ocampo A, Liu GH, Izpisua Belmonte JC. 2013; Mitochondrial regulation in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Metab. 18:325–332. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.005. PMID: 23850316.

Article8. Grishko V, Xu M, Ho R, Mates A, Watson S, Kim JT, Wilson GL, Pearsall AW 4th. 2009; Effects of hyaluronic acid on mitochondrial function and mitochondria-driven apoptosis following oxidative stress in human chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 284:9132–9139. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M804178200. PMID: 19193642. PMCID: PMC2666563.

Article9. Cyphert JM, Trempus CS, Garantziotis S. 2015; Size matters: molecular weight specificity of hyaluronan effects in cell biology. Int J Cell Biol. 2015:563818. DOI: 10.1155/2015/563818. PMID: 26448754. PMCID: PMC4581549.

Article10. Liu RM, Sun RG, Zhang LT, Zhang QF, Chen DX, Zhong JJ, Xiao JH. 2016; Hyaluronic acid enhances proliferation of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res. 345:218–229. DOI: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.05.019. PMID: 27237096.

Article11. Joddar B, Kitajima T, Ito Y. 2011; The effects of covalently immobilized hyaluronic acid substrates on the adhesion, expansion, and differentiation of embryonic stem cells for in vitro tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 32:8404–8415. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.083. PMID: 21871660.

Article12. Liu CM, Chang CH, Yu CH, Hsu CC, Huang LL. 2009; Hyaluronan substratum induces multidrug resistance in human mesenchymal stem cells via CD44 signaling. Cell Tissue Res. 336:465–475. DOI: 10.1007/s00441-009-0780-3. PMID: 19350274.

Article13. Lonergan T, Brenner C, Bavister B. 2006; Differentiation-related changes in mitochondrial properties as indicators of stem cell competence. J Cell Physiol. 208:149–153. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.20641. PMID: 16575916.

Article14. Wong TY, Chen YH, Liu SH, Solis MA, Yu CH, Chang CH, Huang LL. 2016; Differential proteomic analysis of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured on normal tissue culture surface and hyaluronan-coated surface. Stem Cells Int. 2016:2809192. DOI: 10.1155/2016/2809192. PMID: 27057169. PMCID: PMC4709773.

Article15. Kunze R, Rösler M, Möller S, Schnabelrauch M, Riemer T, Hempel U, Dieter P. 2010; Sulfated hyaluronan derivatives reduce the proliferation rate of primary rat calvarial osteoblasts. Glycoconj J. 27:151–158. DOI: 10.1007/s10719-009-9270-9. PMID: 19941065.

Article16. Vazin T, Freed WJ. 2010; Human embryonic stem cells: derivation, culture, and differentiation: a review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 28:589–603. DOI: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0543. PMID: 20714081. PMCID: PMC2973558.

Article17. Chen WY, Abatangelo G. 1999; Functions of hyaluronan in wound repair. Wound Repair Regen. 7:79–89. DOI: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1999.00079.x. PMID: 10231509.

Article18. Forman DS, Lynch KJ, Smith RS. 1987; Organelle dynamics in lobster axons: anterograde, retrograde and stationary mitochondria. Brain Res. 412:96–106. DOI: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91443-0. PMID: 3607465.

Article19. Frederick RL, Shaw JM. 2007; Moving mitochondria: establishing distribution of an essential organelle. Traffic. 8:1668–1675. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00644.x. PMID: 17944806. PMCID: PMC3739988.

Article20. Murphy MP. 2012; Modulating mitochondrial intracellular location as a redox signal. Sci Signal. 5:pe39. DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2003386. PMID: 22990116.

Article21. Mandal S, Lindgren AG, Srivastava AS, Clark AT, Banerjee U. 2011; Mitochondrial function controls proliferation and early differentiation potential of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 29:486–495. DOI: 10.1002/stem.590. PMID: 21425411. PMCID: PMC4374603.

Article22. Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. 2010; The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 28:721–733. DOI: 10.1002/stem.404. PMID: 20201066.

Article23. Smith ER, Zhang XY, Capo-Chichi CD, Chen X, Xu XX. 2011; Increased expression of Syne1/nesprin-1 facilitates nuclear envelope structure changes in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 240:2245–2255. DOI: 10.1002/dvdy.22717. PMID: 21932307. PMCID: PMC3290128.

Article24. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. 2009; Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. DOI: 10.1126/science.1160809. PMID: 19460998. PMCID: PMC2849637.

Article25. Lakshman M, Subramaniam V, Rubenthiran U, Jothy S. 2004; CD44 promotes resistance to apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 77:18–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2004.03.002. PMID: 15215046.

Article26. Nolan MJ, Koga T, Walker L, McCarty R, Grybauskas A, Giovingo MC, Skuran K, Kuprys PV, Knepper PA. 2013; sCD44 internalization in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 54:592–601. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.12-10627. PMID: 23287794. PMCID: PMC3558300.

Article27. Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Arrell DK, Lindor JZ, Dzeja PP, Ikeda Y, Perez-Terzic C, Terzic A. 2011; Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab. 14:264–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.011. PMID: 21803296. PMCID: PMC3156138.

Article28. Guo HW, Yu JS, Hsu SH, Wei YH, Lee OK, Dong CY, Wang HW. 2015; Correlation of NADH fluorescence lifetime and oxidative phosphorylation metabolism in the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cell. J Biomed Opt. 20:017004. DOI: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.1.017004. PMID: 25629291.

Article29. Son MJ, Jeong BR, Kwon Y, Cho YS. 2013; Interference with the mitochondrial bioenergetics fuels reprogramming to pluripotency via facilitation of the glycolytic transition. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 45:2512–2518. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.07.023. PMID: 23939289.

Article30. Wu SB, Wei YH. 2012; AMPK-mediated increase of glycolysis as an adaptive response to oxidative stress in human cells: implication of the cell survival in mitochondrial diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1822:233–247. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.014. PMID: 22001850.

Article31. Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. 2012; Metabolic regulation in pluripotent stem cells during reprogramming and self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 11:589–595. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.005. PMID: 23122286. PMCID: PMC3492890.

Article32. Zhang L, Marsboom G, Glick D, Zhang Y, Toth PT, Jones N, Malik AB, Rehman J. 2014; Bioenergetic shifts during transitions between stem cell states (2013 Grover Conference series). Pulm Circ. 4:387–394. DOI: 10.1086/677353. PMID: 25621152. PMCID: PMC4278598.

Article33. Birket MJ, Orr AL, Gerencser AA, Madden DT, Vitelli C, Swistowski A, Brand MD, Zeng X. 2011; A reduction in ATP demand and mitochondrial activity with neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 124:348–358. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.072272. PMID: 21242311. PMCID: PMC3021997.

Article34. Darzynkiewicz Z, Balazs EA. 2012; Genome integrity, stem cells and hyaluronan. Aging (Albany NY). 4:78–88. DOI: 10.18632/aging.100438. PMID: 22383371. PMCID: PMC3314170.

Article35. Saha P, Chowdhury AR, Dutta S, Chatterjee S, Ghosh I, Datta K. 2013; Autophagic vacuolation induced by excess ROS generation in HABP1/p32/gC1qR overexpressing fibroblasts and its reversal by polymeric hyaluronan. PLoS One. 8:e78131. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078131. PMID: 24205125. PMCID: PMC3799741.

Article36. El-Safory NS, Lee CK. 2010; Cytotoxic and antioxidant effects of unsaturated hyaluronic acid oligomers. Carbohydr Polym. 82:1116–1123. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.042.

Article37. Zhao H, Tanaka T, Mitlitski V, Heeter J, Balazs EA, Darzynkiewicz Z. 2008; Protective effect of hyaluronate on oxidative DNA damage in WI-38 and A549 cells. Int J Oncol. 32:1159–1167. DOI: 10.3892/ijo_32_6_1159. PMID: 18497977. PMCID: PMC2581747.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Recent Trends and Strategies in Stem Cell Therapy for Alzheimer's Disease

- Minimal Cube Explant Provides Optimal Isolation Condition of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Umbilical Cord

- Concise Review: Differentiation of Human Adult Stem Cells Into Hepatocyte-like Cells In vitro

- Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Patients with Nontraumatic Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head

- Role of Gastric Stem Cells in Gastric Carcinogenesis by Chronic Helicobacter pylori Infection