Endocrinol Metab.

2020 Mar;35(1):55-63. 10.3803/EnM.2020.35.1.55.

Potential Biomarkers to Improve the Prediction of Osteoporotic Fractures

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. umkbj0825@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 2471720

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2020.35.1.55

Abstract

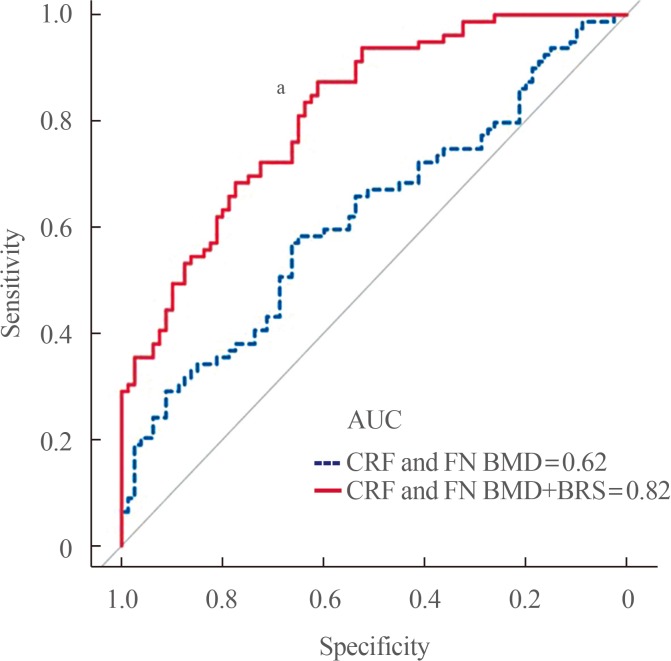

- Osteoporotic fracture (OF) is associated with high disability and morbidity rates. The burden of OF may be reduced by early identification of subjects who are vulnerable to fracture. Although the current fracture risk assessment model includes clinical risk factors (CRFs) and bone mineral density (BMD), its overall ability to identify individuals at high risk for fracture remains suboptimal. Efforts have therefore been made to identify potential biomarkers that can predict the risk of OF, independent of or combined with CRFs and BMD. This review highlights the emerging biomarkers of bone metabolism, including sphongosine-1-phosphate, leucine-rich repeat-containing 17, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, sclerostin, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, and periostin, and the importance of biomarker risk score, generated by combining these markers, in enhancing the accuracy of fracture prediction.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Update on Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

Soo-Kyung Cho, Yoon-Kyoung Sung

Endocrinol Metab. 2021;36(3):536-543. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1021.

Reference

-

1. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001; 285:785–795. PMID: 11176917.2. Bae G, Kim E, Kwon HY, An J, Park J, Yang H. Disability weights for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures in South Korea. J Bone Metab. 2019; 26:83–88. PMID: 31223604.

Article3. Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009; 301:513–521. PMID: 19190316.

Article4. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007; 22:465–475. PMID: 17144789.

Article5. Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Bone strength and its determinants. Osteoporos Int. 2003; 14 Suppl 3:S13–S18. PMID: 12730800.

Article6. Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994; 9:1137–1141. PMID: 7976495.

Article7. Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ. 1996; 312:1254–1259. PMID: 8634613.

Article8. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008; 19:385–397. PMID: 18292978.

Article9. Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Drewniak N, Laparra J, Ribot CA, Dargent-Molina P. Fracture risk prediction using BMD and clinical risk factors in early postmenopausal women: sensitivity of the WHO FRAX tool. J Bone Miner Res. 2010; 25:1002–1009. PMID: 20200927.

Article10. Kim BJ, Koh JM. Coupling factors involved in preserving bone balance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019; 76:1243–1253. PMID: 30515522.

Article11. Garnero P. The utility of biomarkers in osteoporosis management. Mol Diagn Ther. 2017; 21:401–418. PMID: 28271451.

Article12. Park SY, Ahn SH, Yoo JI, Chung YJ, Jeon YK, Yoon BH, et al. Clinical application of bone turnover markers in osteoporosis in Korea. J Bone Metab. 2019; 26:19–24. PMID: 30899720.

Article13. Vasikaran S, Eastell R, Bruyere O, Foldes AJ, Garnero P, Griesmacher A, et al. Markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture risk and monitoring of osteoporosis treatment: a need for international reference standards. Osteoporos Int. 2011; 22:391–420. PMID: 21184054.

Article14. Morris HA, Eastell R, Jorgensen NR, Cavalier E, Vasikaran S, Chubb SAP, et al. Clinical usefulness of bone turnover marker concentrations in osteoporosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2017; 467:34–41. PMID: 27374301.

Article15. Yoo JI, Park AJ, Lim YK, Kweon OJ, Choi JH, Do JH, et al. Age-related reference intervals for total collagen-I-N-terminal propeptide in healthy Korean population. J Bone Metab. 2018; 25:235–241. PMID: 30574468.

Article16. Szulc P. Bone turnover: biology and assessment tools. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018; 32:725–738. PMID: 30449551.

Article17. Yoon BH, Yu W. Clinical utility of biochemical marker of bone turnover: fracture risk prediction and bone healing. J Bone Metab. 2018; 25:73–78. PMID: 29900156.

Article18. Garnero P, Hausherr E, Chapuy MC, Marcelli C, Grandjean H, Muller C, et al. Markers of bone resorption predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS Prospective Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1996; 11:1531–1538. PMID: 8889854.

Article19. Garnero P, Cloos P, Sornay-Rendu E, Qvist P, Delmas PD. Type I collagen racemization and isomerization and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women: the OFELY prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2002; 17:826–833. PMID: 12009013.

Article20. Johansson H, Oden A, Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Morris HA, Cooper C, et al. A meta-analysis of reference markers of bone turnover for prediction of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014; 94:560–567. PMID: 24590144.

Article21. Ross PD, Kress BC, Parson RE, Wasnich RD, Armour KA, Mizrahi IA. Serum bone alkaline phosphatase and calcaneus bone density predict fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2000; 11:76–82. PMID: 10663362.

Article22. Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, Halleen JM, Hellman J, Isaksson A, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004; 19:386–393. PMID: 15040826.

Article23. Marques EA, Gudnason V, Lang T, Sigurdsson G, Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, et al. Association of bone turnover markers with volumetric bone loss, periosteal apposition, and fracture risk in older men and women: the AGES-Reykjavik longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int. 2016; 27:3485–3494. PMID: 27341810.

Article24. Melton LJ 3rd, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Wahner HW, Riggs BL. Relative contributions of bone density, bone turnover, and clinical risk factors to long-term fracture prediction. J Bone Miner Res. 2003; 18:312–318. PMID: 12568408.

Article25. Rosen H, Goetzl EJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and its receptors: an autocrine and paracrine network. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005; 5:560–570. PMID: 15999095.

Article26. Grey A, Xu X, Hill B, Watson M, Callon K, Reid IR, et al. Osteoblastic cells express phospholipid receptors and phosphatases and proliferate in response to sphingosine-1-phosphate. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004; 74:542–550. PMID: 15354862.

Article27. Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009; 458:524–528. PMID: 19204730.

Article28. Grey A, Chen Q, Callon K, Xu X, Reid IR, Cornish J. The phospholipids sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid prevent apoptosis in osteoblastic cells via a signaling pathway involving G(i) proteins and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Endocrinology. 2002; 143:4755–4763. PMID: 12446603.

Article29. Roelofsen T, Akkers R, Beumer W, Apotheker M, Steeghs I, van de, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate acts as a developmental stage specific inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor-induced chemotaxis of osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2008; 105:1128–1138. PMID: 18819098.

Article30. Lotinun S, Kiviranta R, Matsubara T, Alzate JA, Neff L, Luth A, et al. Osteoclast-specific cathepsin K deletion stimulates S1P-dependent bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2013; 123:666–681. PMID: 23321671.

Article31. Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y, Kim HH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. EMBO J. 2006; 25:5840–5851. PMID: 17124500.

Article32. Ishii M, Kikuta J, Shimazu Y, Meier-Schellersheim M, Germain RN. Chemorepulsion by blood S1P regulates osteoclast precursor mobilization and bone remodeling in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010; 207:2793–2798. PMID: 21135136.

Article33. Lee SH, Lee SY, Lee YS, Kim BJ, Lim KH, Cho EH, et al. Higher circulating sphingosine 1-phosphate levels are associated with lower bone mineral density and higher bone resorption marker in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:E1421–E1428. PMID: 22679064.

Article34. Kim BJ, Shin KO, Kim H, Ahn SH, Lee SH, Seo CH, et al. The effect of sphingosine-1-phosphate on bone metabolism in humans depends on its plasma/bone marrow gradient. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016; 39:297–303. PMID: 26219613.

Article35. Peest U, Sensken SC, Andreani P, Hanel P, Van Veldhoven PP, Graler MH. S1P-lyase independent clearance of extracellular sphingosine 1-phosphate after dephosphorylation and cellular uptake. J Cell Biochem. 2008; 104:756–772. PMID: 18172856.

Article36. Zhao Y, Kalari SK, Usatyuk PV, Gorshkova I, He D, Watkins T, et al. Intracellular generation of sphingosine 1-phosphate in human lung endothelial cells: role of lipid phosphate phosphatase-1 and sphingosine kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282:14165–14177. PMID: 17379599.37. Kim BJ, Koh JM, Lee SY, Lee YS, Lee SH, Lim KH, et al. Plasma sphingosine 1-phosphate levels and the risk of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:3807–3814. PMID: 22879631.

Article38. Bae SJ, Lee SH, Ahn SH, Kim HM, Kim BJ, Koh JM. The circulating sphingosine-1-phosphate level predicts incident fracture in postmenopausal women: a 3.5-year follow-up observation study. Osteoporos Int. 2016; 27:2533–2541. PMID: 26984570.

Article39. Ardawi MM, Rouzi AA, Al-Senani NS, Qari MH, Elsamanoudy AZ, Mousa SA. High plasma sphingosine 1-phosphate levels predict osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women: the center of excellence for osteoporosis research study. J Bone Metab. 2018; 25:87–98. PMID: 29900158.

Article40. Kim D, LaQuaglia MP, Yang SY. A cDNA encoding a putative 37 kDa leucine-rich repeat (LRR) protein, p37NB, isolated from S-type neuroblastoma cell has a differential tissue distribution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996; 1309:183–188. PMID: 8982252.

Article41. Kim T, Kim K, Lee SH, So HS, Lee J, Kim N, et al. Identification of LRRc17 as a negative regulator of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:15308–15316. PMID: 19336404.42. Hong N, Kim BJ, Kim CH, Baek KH, Min YK, Kim DY, et al. Low plasma level of leucine-rich repeat-containing 17 (LRRc17) is an independent and additive risk factor for osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2016; 31:2106–2114. PMID: 27355564.

Article43. Kim BS, Pallua N, Bernhagen J, Bucala R. The macrophage migration inhibitory factor protein superfamily in obesity and wound repair. Exp Mol Med. 2015; 47:e161. PMID: 25930990.

Article44. Onodera S, Sasaki S, Ohshima S, Amizuka N, Li M, Udagawa N, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) exhibit high-turnover osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2006; 21:876–885. PMID: 16753018.

Article45. Oshima S, Onodera S, Amizuka N, Li M, Irie K, Watanabe S, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor-deficient mice are resistant to ovariectomy-induced bone loss. FEBS Lett. 2006; 580:1251–1256. PMID: 16442103.

Article46. Kim H, Ahn SH, Shin C, Lee SH, Kim BJ, Koh JM. The association of higher plasma macrophage migration inhibitory factor levels with lower bone mineral density and higher bone turnover rate in postmenopausal women. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2016; 31:454–461. PMID: 27469066.

Article47. Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005; 8:739–750. PMID: 15866164.48. Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Hovhannisyan H, Bhat RA, Bodine PV, Komm BS, et al. Canonical WNT signaling promotes osteogenesis by directly stimulating Runx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:33132–33140. PMID: 16043491.

Article49. Semenov M, Tamai K, He X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:26770–26775. PMID: 15908424.50. Wijenayaka AR, Kogawa M, Lim HP, Bonewald LF, Findlay DM, Atkins GJ. Sclerostin stimulates osteocyte support of osteoclast activity by a RANKL-dependent pathway. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e25900. PMID: 21991382.

Article51. Ardawi MS, Al-Kadi HA, Rouzi AA, Qari MH. Determinants of serum sclerostin in healthy pre- and postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2011; 26:2812–2822. PMID: 21812027.

Article52. Drake MT, Srinivasan B, Modder UI, Peterson JM, McCready LK, Riggs BL, et al. Effects of parathyroid hormone treatment on circulating sclerostin levels in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 95:5056–5062. PMID: 20631014.

Article53. Arasu A, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, Do TP, Arora PS, Cauley JA, et al. Serum sclerostin and risk of hip fracture in older Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:2027–2032. PMID: 22466341.

Article54. Ardawi MS, Rouzi AA, Al-Sibiani SA, Al-Senani NS, Qari MH, Mousa SA. High serum sclerostin predicts the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women: the Center of Excellence for Osteoporosis Research Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2012; 27:2592–2602. PMID: 22836717.

Article55. Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Borel O, Chapurlat RD. Association of serum sclerostin with bone mineral density, bone turnover, steroid and parathyroid hormones, and fracture risk in postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. Osteoporos Int. 2013; 24:489–494. PMID: 22525978.

Article56. Szulc P, Bertholon C, Borel O, Marchand F, Chapurlat R. Lower fracture risk in older men with higher sclerostin concentration: a prospective analysis from the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2013; 28:855–864. PMID: 23165952.

Article57. Lim Y, Kim CH, Lee SY, Kim H, Ahn SH, Lee SH, et al. Decreased plasma levels of sclerostin but not dickkopf-1 are associated with an increased prevalence of osteoporotic fracture and lower bone mineral density in postmenopausal Korean women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016; 99:350–359. PMID: 27289555.

Article58. Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003; 423:337–342. PMID: 12748652.

Article59. Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kurata K, Oh-Hora M, Feng JQ, et al. Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through RANKL expression. Nat Med. 2011; 17:1231–1234. PMID: 21909105.

Article60. Xiong J, Piemontese M, Onal M, Campbell J, Goellner JJ, Dusevich V, et al. Osteocytes, not osteoblasts or lining cells, are the main source of the RANKL required for osteoclast formation in remodeling bone. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0138189. PMID: 26393791.

Article61. Findlay DM, Atkins GJ. Relationship between serum RANKL and RANKL in bone. Osteoporos Int. 2011; 22:2597–2602. PMID: 21850548.

Article62. Piatek S, Adolf D, Wex T, Halangk W, Klose S, Westphal S, et al. Multiparameter analysis of serum levels of C-telopeptide crosslaps, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, cathepsin K, osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand in the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2013; 74:363–368. PMID: 23391500.

Article63. Uemura H, Yasui T, Miyatani Y, Yamada M, Hiyoshi M, Arisawa K, et al. Circulating profiles of osteoprotegerin and soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008; 31:163–168. PMID: 18362509.64. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guanabens N, Vidal S, Ros I, Pons F, et al. Serum osteoprotegerin and its ligand in Paget's disease of bone: relationship to disease activity and effect of treatment with bisphosphonates. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 48:824–828. PMID: 12632438.

Article65. Findlay D, Chehade M, Tsangari H, Neale S, Hay S, Hopwood B, et al. Circulating RANKL is inversely related to RANKL mRNA levels in bone in osteoarthritic males. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008; 10:R2. PMID: 18182105.

Article66. Takeshita S, Kikuno R, Tezuka K, Amann E. Osteoblast-specific factor 2: cloning of a putative bone adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I. Biochem J. 1993; 294:271–278. PMID: 8363580.

Article67. Merle B, Garnero P. The multiple facets of periostin in bone metabolism. Osteoporos Int. 2012; 23:1199–1212. PMID: 22310955.

Article68. Bonnet N, Standley KN, Bianchi EN, Stadelmann V, Foti M, Conway SJ, et al. The matricellular protein periostin is required for sost inhibition and the anabolic response to mechanical loading and physical activity. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:35939–35950. PMID: 19837663.

Article69. Bonnet N, Conway SJ, Ferrari SL. Regulation of beta catenin signaling and parathyroid hormone anabolic effects in bone by the matricellular protein periostin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109:15048–15053. PMID: 22927401.

Article70. Szulc P, Garnero P, Marchand F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone formation reflect endosteal bone loss in elderly men: MINOS study. Bone. 2005; 36:13–21. PMID: 15663998.71. Rousseau JC, Sornay-Rendu E, Bertholon C, Chapurlat R, Garnero P. Serum periostin is associated with fracture risk in postmenopausal women: a 7-year prospective analysis of the OFELY study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 99:2533–2539. PMID: 24628551.

Article72. Kim BJ, Rhee Y, Kim CH, Baek KH, Min YK, Kim DY, et al. Plasma periostin associates significantly with non-vertebral but not vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women: Clinical evidence for the different effects of periostin depending on the skeletal site. Bone. 2015; 81:435–441. PMID: 26297442.

Article73. Nakazawa T, Nakajima A, Seki N, Okawa A, Kato M, Moriya H, et al. Gene expression of periostin in the early stage of fracture healing detected by cDNA microarray analysis. J Orthop Res. 2004; 22:520–525. PMID: 15099630.

Article74. Kim H, Baek KH, Lee SY, Ahn SH, Lee SH, Koh JM, et al. Association of circulating dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 levels with osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2017; 28:1099–1108. PMID: 27866216.

Article75. Kim BJ, Lee YS, Lee SY, Baek WY, Choi YJ, Moon SA, et al. Osteoclast-secreted SLIT3 coordinates bone resorption and formation. J Clin Invest. 2018; 128:1429–1441. PMID: 29504949.

Article76. Prezelj J, Ostanek B, Logar DB, Marc J, Hawa G, Kocjan T. Cathepsin K predicts femoral neck bone mineral density change in nonosteoporotic peri- and early postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008; 15:369–373. PMID: 17882010.

Article77. Mirza MA, Karlsson MK, Mellstrom D, Orwoll E, Ohlsson C, Ljunggren O, et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) and fracture risk in elderly men. J Bone Miner Res. 2011; 26:857–864. PMID: 20928885.

Article78. Huang X, Qin G, Fang Y. Optimal combinations of diagnostic tests based on AUC. Biometrics. 2011; 67:568–576. PMID: 20560934.

Article79. McClung MR. Emerging therapies for osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015; 30:429–435. PMID: 26354487.

Article80. Min YK. Update on denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015; 30:19–26. PMID: 25827453.

Article81. McClung MR, Grauer A, Boonen S, Bolognese MA, Brown JP, Diez-Perez A, et al. Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:412–420. PMID: 24382002.

Article82. Bekker PJ, Holloway DL, Rasmussen AS, Murphy R, Martin SW, Leese PT, et al. A single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG 162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004; 19:1059–1066. PMID: 15176987.

Article83. Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:756–765. PMID: 19671655.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Utility of Biochemical Marker of Bone Turnover: Fracture Risk Prediction and Bone Healing

- Clinical Utility of Novel Biomarkers in the Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease

- Osteoporotic Hip Fracture: How We Make Better Results?

- Current Concepts of Vitamin D and Calcium in the Healing of Fractures

- The Epidemiology and Importance of Osteoporotic Spinal Compression Fracture in South Korea