Korean J Gastroenterol.

2019 Mar;73(3):182-185. 10.4166/kjg.2019.73.3.182.

Pancreatic Metastasis from Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea. youreon.park@gmail.com

- 2Department of Anatomic Pathology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 3Department of Radiology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- KMID: 2442085

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2019.73.3.182

Abstract

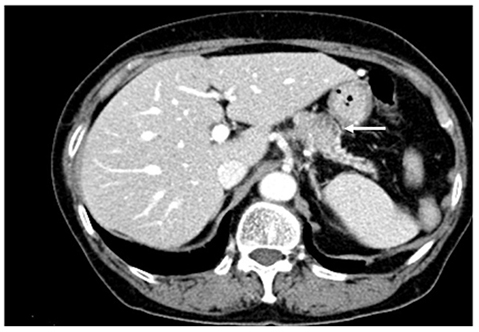

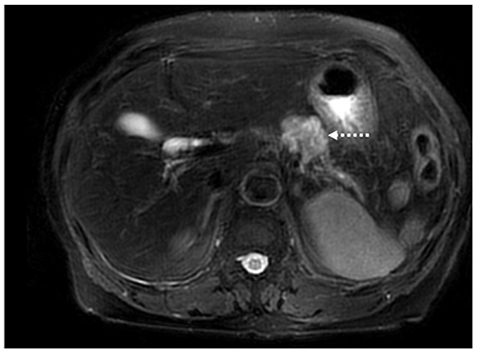

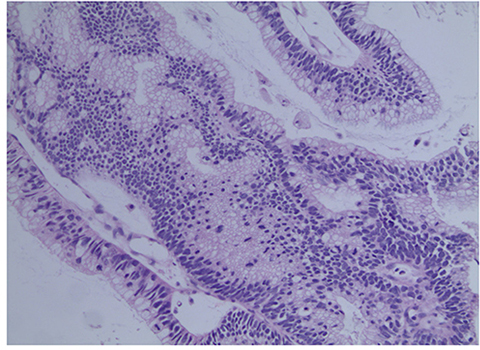

- Pancreatic metastasis from cervical cancer is extremely rare. We report a case of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas from uterine cervical cancer. A 70-year-old woman was referred because of a pancreatic mass detected by CT. She had been diagnosed with uterine cervical adenocarcinoma 20 months previously. After concurrent chemoradiotherapy, CT showed no evidence of the cervical mass, and follow-up showed no evidence of recurrence. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreatic mass resulted in a diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma from uterine cervix.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kuwatani M, Kawakami H, Asaka M, Marukawa K, Matsuno Y, Hosaka M. Pancreatic metastasis from small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix demonstrated by endoscopic ultrasonographyguided fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008; 36:840–842.

Article2. Mackay B, Osborne BM, Wharton JT. Small cell tumor of cervix with neuroepithelial features: ultrastructural observations in two cases. Cancer. 1979; 43:1138–1145.3. Ogawa H, Tsujie M, Miyamoto A, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from uterine cervical cancer: a case report. Pancreas. 2011; 40:797–798.4. Nishimura C, Naoe H, Hashigo S, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2013; 6:256–262.

Article5. Wastell C. A solitary secondary deposit in the pancreas from a carcinoma of the cervix. Postgrad Med J. 1966; 42:59–61.

Article6. Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Cautero N, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: the state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2011; 17:4747–4756.

Article7. Takeuchi S. Biology and treatment of cervical adenocarcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016; 28:254–262.

Article8. Mahajan S, Pandit-Taskar N. Uncommon metastasis to the pancreas from adenocarcinoma of the cervix detected on surveillance 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2017; 42:e511–e512.

Article9. Choi TW, Kim SH, Shin CI, Han JK, Choi BI. MDCT findings of pancreatic metastases according to primary tumors. Abdom Imaging. 2015; 40:1595–1607.

Article10. Chu PG, Schwarz RE, Lau SK, Yen Y, Weiss LM. Immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of pancreatobiliary and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma: application of CDX2, CK17, MUC1, and MUC2. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:359–367.11. McCluggage WG, Shah R, Connolly LE, McBride HA. Intestinaltype cervical adenocarcinoma in situ and adenocarcinoma exhibit a partial enteric immunophenotype with consistent expression of CDX2. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27:92–100.

Article12. Ohtsubo K, Watanabe H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Abnormalities of tumor suppressor gene p16 in pancreatic carcinoma: immunohistochemical and genetic findings compared with clinicopathological parameters. J Gastroenterol. 2003; 38:663–671.

Article13. Doxtader EE, Katzenstein AL. The relationship between p16 expression and high-risk human papillomavirus infection in squamous cell carcinomas from sites other than uterine cervix: a study of 137 cases. Hum Pathol. 2012; 43:327–332.

Article14. Tong TR, Chan A, Lai TW, et al. Identification of HPV-16 in borderline mucinous cystic neoplasm of pancreas. Int J Biomed Sci. 2007; 3:72–75.15. de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11:1048–1056.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Cervical Adenocarcinoma with Pulmonary Metastasis Resembling Miliary Tuberculosis

- Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix in a 15-Year-Old Girl: A Case Report

- Ovarian Mucinous Adenocarcinoma Associated with Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix

- A Case of Primary Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix

- The Clinicopathological Analysis of Adenocarcinoma and Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix