Clin Orthop Surg.

2018 Sep;10(3):380-384. 10.4055/cios.2018.10.3.380.

The Influence of Antiplatelet Drug Medication on Spine Surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedics, Seoul Sacred Heart General Hospital, Seoul, Korea. adk0208@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2418760

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2018.10.3.380

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The incidence of cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases has been increasing with the aging of the population, and antiplatelet drugs (APDs) are more frequently used than in the past. With the average age of spinal surgery patients also increasing, there has been a great concern on the adverse effects of APD on spine surgery. To our knowledge, though there have been many studies on this issue, their results are conflicting. In this study, we aimed to determine the influence of APDs on spine surgery in terms of intraoperative bleeding and postoperative spinal epidural hematoma complication.

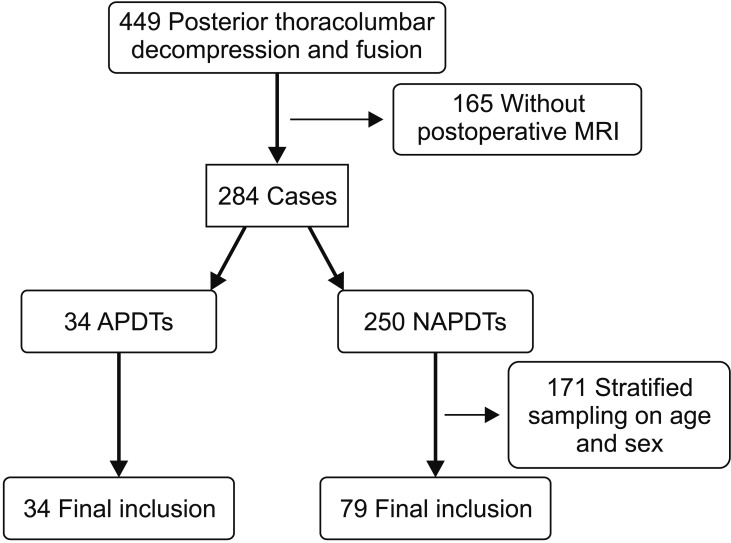

METHODS

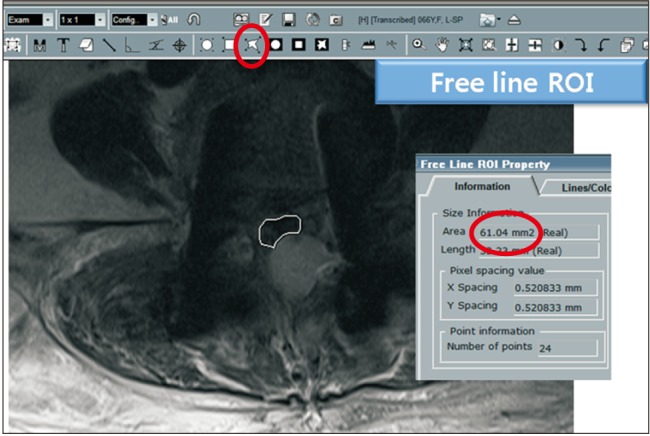

Patients who underwent posterior thoracolumbar decompression and instrumentation at our institution were reviewed. There were 34 APD takers (APDT group). Seventy-nine non-APD takers (NAPDT group) were selected as a control group in consideration of demographic and surgical factors. There were two primary endpoints of this study: the amount of bleeding per 10 minutes and cauda equina compression by epidural hematoma measured at the cross-sectional area of the thecal sac in the maximal compression site on the axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging scans taken on day 7.

RESULTS

Both groups were homogeneous regarding age and sex (demographic factors), the number of fused segments, operation time, and primary/revision operation (surgical factors), and the number of platelets, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time (coagulation-related factors). However, the platelet function analysis-epinephrine was delayed in the APDT group than in the NAPDT group (203.6 seconds vs. 170.0 seconds, p = 0.050). Intraoperative bleeding per 10 minutes was 40.6 ± 12.8 mL in the APDT group and 43.9 ± 9.9 mL in the NAPDT group, showing no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.154). The cross-sectional area of the thecal sac at the maximal compression site by epidural hematoma was 120.2 ± 48.2 mm2 in the APDT group and 123.2 ± 50.4 mm2 in the NAPDT group, showing no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.766).

CONCLUSIONS

APD medication did not increase intraoperative bleeding and postoperative spinal epidural hematoma. Therefore, it would be safer to perform spinal surgery without discontinuation of APD therapy in patients who are vulnerable to cardiovascular and neurovascular complications.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Chassot PG, Marcucci C, Delabays A, Spahn DR. Perioperative antiplatelet therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2010; 82(12):1484–1489. PMID: 21166368.2. Komiya R, Kamintani K, Kubo E, et al. Perioperative management and postoperative complication rates of patients on dual antiplatelet therapies after coronary drug eluting stent implantation. Masui. 2014; 63(6):629–635. PMID: 24979851.3. Wahl MJ. Dental surgery and antiplatelet agents: bleed or die. Am J Med. 2014; 127(4):260–267. PMID: 24333202.

Article4. Libanio D, Costa MN, Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Risk factors for bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016; 84(4):572–586. PMID: 27345132.5. Cuellar JM, Petrizzo A, Vaswani R, Goldstein JA, Bendo JA. Does aspirin administration increase perioperative morbidity in patients with cardiac stents undergoing spinal surgery? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015; 40(9):629–635. PMID: 26030214.

Article6. Smilowitz NR, Oberweis BS, Nukala S, et al. Perioperative antiplatelet therapy and cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing joint and spine surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2016; 35:163–169. PMID: 27871515.

Article7. Soleman J, Baumgarten P, Perrig WN, Fandino J, Fathi AR. Non-instrumented extradural lumbar spine surgery under low-dose acetylsalicylic acid: a comparative risk analysis study. Eur Spine J. 2016; 25(3):732–739. PMID: 25757534.

Article8. Mishima K, Aritake K, Morita A, Miyagawa N, Segawa H, Sano K. A case of acute spinal epidural hematoma in a patient with antiplatelet therapy. No Shinkei Geka. 1989; 17(9):849–853. PMID: 2797370.9. Weber J, Hoch A, Kilisek L, Spring A. Spontaneous intraspinal epidural hematoma secondary to use of platelet aggregation inhibitors. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001; 126(31-32):876–878. PMID: 11569370.10. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345(7):494–502. PMID: 11519503.

Article11. To AC, Armstrong G, Zeng I, Webster MW. Noncardiac surgery and bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2(3):213–221. PMID: 20031718.

Article12. Chen TH, Matyal R. The management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary stents undergoing noncardiac surgery. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010; 14(4):256–273. PMID: 21059610.

Article13. Korinth MC, Gilsbach JM, Weinzierl MR. Low-dose aspirin before spinal surgery: results of a survey among neurosurgeons in Germany. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16(3):365–372. PMID: 16953446.

Article14. Park JH, Ahn Y, Choi BS, et al. Antithrombotic effects of aspirin on 1- or 2-level lumbar spinal fusion surgery: a comparison between 2 groups discontinuing aspirin use before and after 7 days prior to surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013; 38(18):1561–1565. PMID: 23680836.15. Leonardi MA, Zanetti M, Saupe N, Min K. Early postoperative MRI in detecting hematoma and dural compression after lumbar spinal decompression: prospective study of asymptomatic patients in comparison to patients requiring surgical revision. Eur Spine J. 2010; 19(12):2216–2222. PMID: 20556438.

Article16. Samama CM, Geerts WH. Prevention of intraoperative venous thromboembolism: what are the American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition)? Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2009; 28(9 Suppl):S23–S28. PMID: 19875001.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Medications or food before anesthesia to note taking

- Does a Preoperative Temporary Discontinuation of Antiplatelet Medication before Surgery Increase the Allogenic Transfusion Rate and Blood Loss after Total Knee Arthroplasty?

- Antiplatelet Therapy for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients with Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack

- Epistaxis in Patients Taking Oral Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Medication

- Biliary-Pancreatic Endoscopic and Surgical Procedures in Patients under Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: A Single-Center Study