Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2018 Jul;22(4):369-377. 10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.4.369.

Isoliquiritigenin attenuates spinal tuberculosis through inhibiting immune response in a New Zealand white rabbit model

- Affiliations

-

- 1Record Room, Jinan Second People's Hospital, Jinan 250011, Shandong, China.

- 2Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Jinan Second People's Hospital, Jinan 250011, Shandong, China.

- 3Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan Second People's Hospital, Jinan 250011, Shandong, China.

- 4Department of Orthopedics, Shandong Chest Hospital, Jinan 250101, Shandong, China. 13156120768@163.com

- KMID: 2414261

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.4.369

Abstract

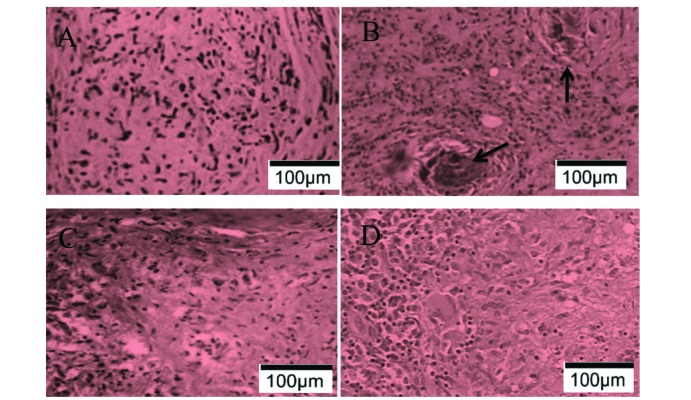

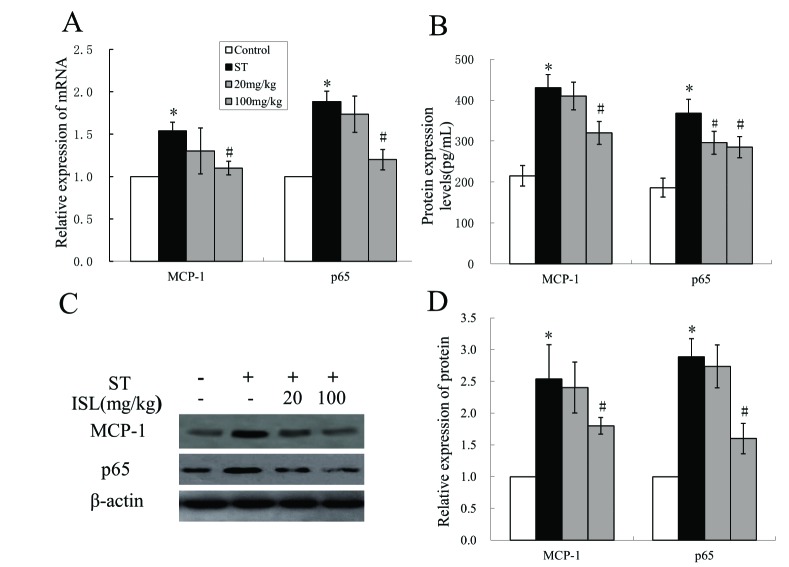

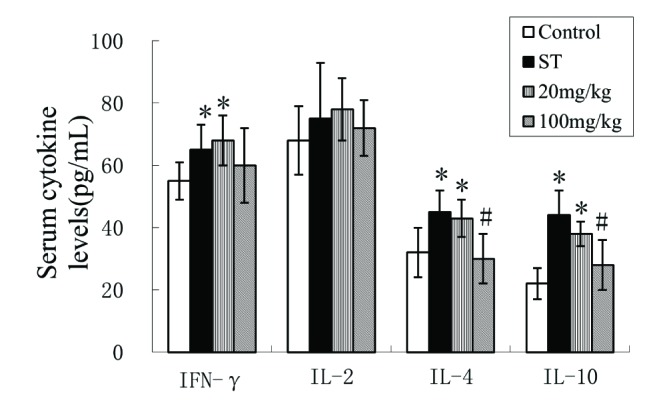

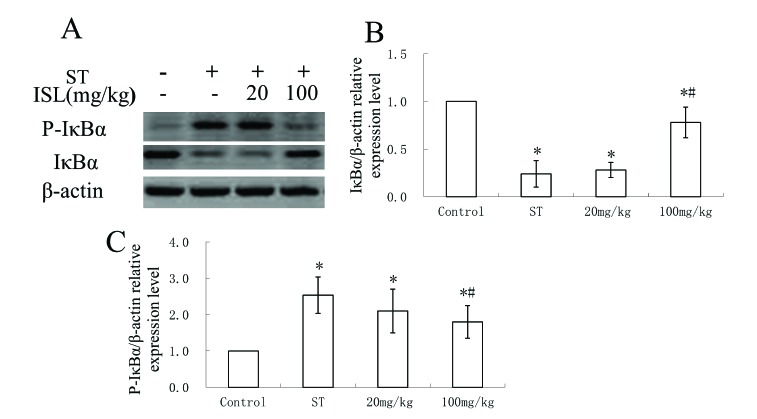

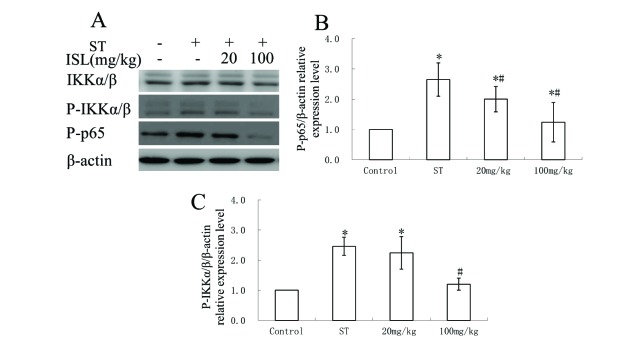

- Spinal tuberculosis (ST) is the tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infections in spinal curds. Isoliquiritigenin 4,2"²,4"²-trihydroxychalcone, ISL) is an anti-inflammatory flavonoid derived from licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis), a Chinese traditional medicine. In this study, we evaluated the potential of ISL in treating ST in New Zealand white rabbit models. In the model, rabbits (n=40) were infected with Mtb strain H37Rv or not in their 6th lumbar vertebral bodies. Since the day of infection, rabbits were treated with 20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg of ISL respectively. After 10 weeks of treatments, the adjacent vertebral bone tissues of rabbits were analyzed through Hematoxylin-Eosin staining. The relative expression of Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), transcription factor κB (NF-κB) p65 in lymphocytes were verified through reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). The serum level of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-10 and interferon γ (IFN-γ) were evaluated through ELISA. The effects of ISL on the phosphorylation of IκBα, IKKα/β and p65 in NF-κB signaling pathways were assessed through western blotting. In the results, ISL has been shown to effectively attenuate the granulation inside adjacent vertebral tissues. The relative level of MCP-1, p65 and IL-4 and IL-10 were retrieved. NF-κB signaling was inhibited, in which the phosphorylation of p65, IκBα and IKKα/β were suppressed whereas the level of IκBα were elevated. In conclusion, ISL might be an effective drug that inhibited the formation of granulomas through downregulating MCP-1, NF-κB, IL-4 and IL-10 in treating ST.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Blotting, Western

Bone and Bones

Chemokine CCL2

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Glycyrrhiza

Granuloma

Interferons

Interleukin-10

Interleukin-4

Interleukins

Lymphocytes

Medicine, Chinese Traditional

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

New Zealand*

Phosphorylation

Rabbits

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Reverse Transcription

Transcription Factors

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, Spinal*

Chemokine CCL2

Interferons

Interleukin-10

Interleukin-4

Interleukins

Transcription Factors

Figure

Reference

-

1. Garg RK, Somvanshi DS. Spinal tuberculosis: a review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011; 34:440–454. PMID: 22118251.

Article2. Kumar K. Spinal tuberculosis, natural history of disease, classifications and principles of management with historical perspective. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016; 26:551–558. PMID: 27435619.

Article3. Danaviah S, Sacks JA, Kumar KP, Taylor LM, Fallows DA, Naicker T, Ndung'u T, Govender S, Kaplan G. Immunohistological characterization of spinal TB granulomas from HIV-negative and -positive patients. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2013; 93:432–441. PMID: 23541388.

Article4. Taylor GM, Murphy E, Hopkins R, Rutland P, Chistov Y. First report of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in human remains from the Iron Age. Microbiology. 2007; 153:1243–1249. PMID: 17379733.

Article5. Rajasekaran S, Khandelwal G. Drug therapy in spinal tuberculosis. Eur Spine J. 2013; 22(Suppl 4):587–593. PMID: 22581190.

Article6. Pawar UM, Kundnani V, Agashe V, Nene A, Nene A. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis of the spine−is it the beginning of the end? A study of twenty-five culture proven multidrug-resistant tuberculosis spine patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 34:E806–E810. PMID: 19829244.7. Hoshino A, Hanada S, Yamada H, Mii S, Takahashi M, Mitarai S, Yamamoto K, Manome Y. Mycobacterium tuberculosis escapes from the phagosomes of infected human osteoclasts reprograms osteoclast development via dysregulation of cytokines and chemokines. Pathog Dis. 2014; 70:28–39. PMID: 23929604.8. World Health Organization. Stop TB Initiative. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010.9. Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the role of the granuloma in tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012; 12:352–366. PMID: 22517424.

Article10. Bold TD, Ernst JD. Who benefits from granulomas, mycobacteria or host? Cell. 2009; 136:17–19. PMID: 19135882.

Article11. Rubin EJ. The granuloma in tuberculosis−friend or foe? N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2471–2473. PMID: 19494225.12. Lin PL, Flynn JL. Understanding latent tuberculosis: a moving target. J Immunol. 2010; 185:15–22. PMID: 20562268.

Article13. Guirado E, Schlesinger LS. Modeling the Mycobacterium tuberculosis granuloma - the critical battlefield in host immunity and disease. Front Immunol. 2013; 4:98. PMID: 23626591.

Article14. Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994; 91:3652–3656. PMID: 8170963.

Article15. Mecabih F, Sadouki F, Bennabi M, Salah S, Boukouaci W, Amroun H, Fortier C, Marzais F, Charron D, Djoudi H, Abbadi MC, Krishnamoorthy R, Tamouza R. Functional polymorphisms of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 gene and Pott's disease risk. Immunobiology. 2016; 221:462–467. PMID: 26626202.

Article16. Fallahi-Sichani M, El-Kebir M, Marino S, Kirschner DE, Linderman JJ. Multiscale computational modeling reveals a critical role for TNF-α receptor 1 dynamics in tuberculosis granuloma formation. J Immunol. 2011; 186:3472–3483. PMID: 21321109.

Article17. Clay H, Volkman HE, Ramakrishnan L. Tumor necrosis factor signaling mediates resistance to mycobacteria by inhibiting bacterial growth and macrophage death. Immunity. 2008; 29:283–294. PMID: 18691913.

Article18. Guo XH, Bai Z, Qiang B, Bu FH, Zhao N. Roles of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 and nuclear factor-κB in immune response to spinal tuberculosis in a New Zealand white rabbit model. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2017; 50:e5625. PMID: 28225889.

Article19. Kwon HM, Choi YJ, Choi JS, Kang SW, Bae JY, Kang IJ, Jun JG, Lee SS, Lim SS, Kang YH. Blockade of cytokine-induced endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression by licorice isoliquiritigenin through NF-kappaB signal disruption. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007; 232:235–245. PMID: 17259331.20. Kim JY, Park SJ, Yun KJ, Cho YW, Park HJ, Lee KT. Isoliquiritigenin isolated from the roots of Glycyrrhiza uralensis inhibits LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression via the attenuation of NF-kappaB in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008; 584:175–184. PMID: 18295200.21. Watanabe Y, Nagai Y, Honda H, Okamoto N, Yamamoto S, Hamashima T, Ishii Y, Tanaka M, Suganami T, Sasahara M, Miyake K, Takatsu K. Isoliquiritigenin attenuates adipose tissue inflammation in vitro and adipose tissue fibrosis through inhibition of innate immune responses in mice. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:23097. PMID: 26975571.

Article22. Du F, Gesang Q, Cao J, Qian M, Ma L, Wu D, Yu H. Isoliquiritigenin attenuates atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2016; 17.

Article23. Chokchaisiri R, Suaisom C, Sriphota S, Chindaduang A, Chuprajob T, Suksamrarn A. Bioactive flavonoids of the flowers of Butea monosperma. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2009; 57:428–432. PMID: 19336944.

Article24. Brown AK, Papaemmanouil A, Bhowruth V, Bhatt A, Dover LG, Besra GS. Flavonoid inhibitors as novel antimycobacterial agents targeting Rv0636, a putative dehydratase enzyme involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis fatty acid synthase II. Microbiology. 2007; 153:3314–3322. PMID: 17906131.25. Gaur R, Thakur JP, Yadav DK, Kapkoti DS, Verma RK, Gupta N, Khan F, Saikia D, Bhakuni RS. Erratum to: Synthesis, antitubercular activity, and molecular modeling studies of analogues of isoliquiritigenin and liquiritigenin, bioactive components from Glycyrrhiza glabra. Med Chem Res. 2015; 24:3772–3774.26. Barry CE 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009; 7:845–855. PMID: 19855401.

Article27. Kim MJ, Wainwright HC, Locketz M, Bekker LG, Walther GB, Dittrich C, Visser A, Wang W, Hsu FF, Wiehart U, Tsenova L, Kaplan G, Russell DG. Caseation of human tuberculosis granulomas correlates with elevated host lipid metabolism. EMBO Mol Med. 2010; 2:258–274. PMID: 20597103.

Article28. Kobayashi S, Miyamoto T, Kimura I, Kimura M. Inhibitory effect of isoliquiritin, a compound in licorice root, on angiogenesis in vivo and tube formation in vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995; 18:1382–1386. PMID: 8593441.

Article29. Wang Z, Wang N, Han S, Wang D, Mo S, Yu L, Huang H, Tsui K, Shen J, Chen J. Dietary compound isoliquiritigenin inhibits breast cancer neoangiogenesis via VEGF/VEGFR-2 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e68566. PMID: 23861918.

Article30. Jhanji V, Liu H, Law K, Lee VY, Huang SF, Pang CP, Yam GH. Isoliquiritigenin from licorice root suppressed neovascularisation in experimental ocular angiogenesis models. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011; 95:1309–1315. PMID: 21719569.

Article31. Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, North R, Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cytokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998; 187:601–608. PMID: 9463410.

Article32. Flores-Villanueva PO, Ruiz-Morales JA, Song CH, Flores LM, Jo EK, Montaño M, Barnes PF, Selman M, Granados J. A functional promoter polymorphism in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is associated with increased susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 2005; 202:1649–1658. PMID: 16352737.

Article33. Fallahi-Sichani M, Kirschner DE, Linderman JJ. NF-κB signaling dynamics play a key role in infection control in tuberculosis. Front Physiol. 2012; 3:170. PMID: 22685435.

Article34. Bai X, Feldman NE, Chmura K, Ovrutsky AR, Su WL, Griffin L, Pyeon D, McGibney MT, Strand MJ, Numata M, Murakami S, Gaido L, Honda JR, Kinney WH, Oberley-Deegan RE, Voelker DR, Ordway DJ, Chan ED. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation decreases survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e61925. PMID: 23634218.

Article35. Liu S, Zhu L, Zhang J, Yu J, Cheng X, Peng B. Anti-osteoclastogenic activity of isoliquiritigenin via inhibition of NF-κB-dependent autophagic pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016; 106:82–93. PMID: 26947453.

Article36. Feldman M, Santos J, Grenier D. Comparative evaluation of two structurally related flavonoids, isoliquiritigenin and liquiritigenin, for their oral infection therapeutic potential. J Nat Prod. 2011; 74:1862–1867. PMID: 21866899.

Article37. Wu Y, Chen X, Ge X, Xia H, Wang Y, Su S, Li W, Yang T, Wei M, Zhang H, Gou L, Li J, Jiang X, Yang J. Isoliquiritigenin prevents the progression of psoriasis-like symptoms by inhibiting NF-κB and proinflammatory cytokines. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016; 94:195–206. PMID: 26383911.

Article38. Yan F, Yang F, Wang R, Yao XJ, Bai L, Zeng X, Huang J, Wong VKW, Lam CWK, Zhou H, Su X, Liu J, Li T, Liu L. Isoliquiritigenin suppresses human T lymphocyte activation via covalently binding cysteine 46 of IκB kinase. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:34223–34235. PMID: 27626700.

Article39. Rook GA, Hernandez-Pando R, Dheda K, Teng Seah G. IL-4 in tuberculosis: implications for vaccine design. Trends Immunol. 2004; 25:483–488. PMID: 15324741.

Article40. Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001; 19:683–765. PMID: 11244051.

Article41. Zhang M, Gong J, Iyer DV, Jones BE, Modlin RL, Barnes PF. T cell cytokine responses in persons with tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Invest. 1994; 94:2435–2442. PMID: 7989601.

Article42. Zhao H, Zhang X, Chen X, Li Y, Ke Z, Tang T, Chai H, Guo AM, Chen H, Yang J. Isoliquiritigenin, a flavonoid from licorice, blocks M2 macrophage polarization in colitis-associated tumorigenesis through downregulating PGE2 and IL-6. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014; 279:311–321. PMID: 25026504.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Immune Response in Tuberculosis

- The Effect of Angiotensin II on Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction in Isolated Rabbit Lung

- An Ovariectomy-Induced Rabbit Osteoporotic Model: A New Perspective

- The Effects of Endothelium Dependent Vasodilator Substances on Rabbit Corpora Cavernosa

- Atypical Form of Multiple Spinal Tuberculosis