Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

2017 Dec;22(4):231-239. 10.6065/apem.2017.22.4.231.

North Korean children: nutrition and growth

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food and Nutrition, Inha University, Incheon, Korea. skleenutrition@inha.ac.kr

- KMID: 2400779

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2017.22.4.231

Abstract

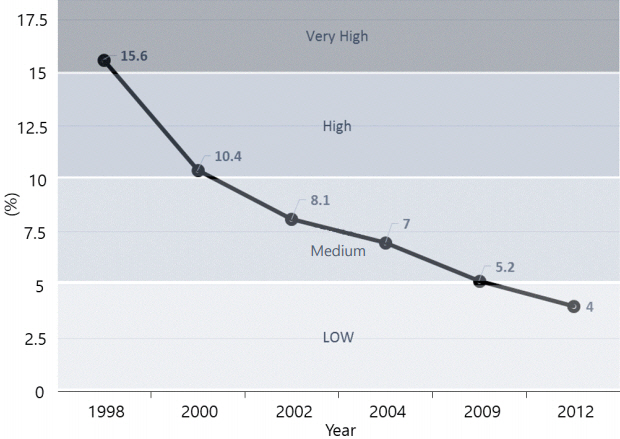

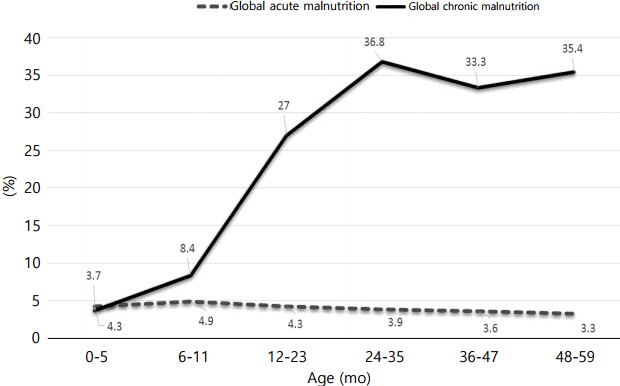

- North Korea suffered from severe famine in the mid-1990s; this impacted many areas, including people's transnational movement, child growth, and mortality. This review carefully examined nutritional status trends of children in North Korea using published reports from national nutrition assessment surveys. Nutritional adaptation of North Korean child refugees living in South Korea was also studied with their growth and food consumption, using published researches. The nutritional status of children in North Korea has recovered to a "low" level acute malnutrition status and a "medium" level chronic malnutrition status. Large disparities by geographic region still remain. North Korean child refugees in South Korea were significantly shorter and lighter than their age- and sex-matched South Korean counterparts (P < 0.05); however, North Korean child refugees were catching up, and weight was improving faster than height. Linear growth retarded (height for age Z-score < -1) North Korean children showed a significantly higher respiratory quotient than nonlinear growth retarded children, indicating metabolic adaptation responding to the food shortage. These changes, accompanied by abundant access to food in South Korea, have led to the elimination of significant differences in the obesity ratio between North Korean and South Korean children living in South Korea after approximately 2 years of residency. This nutritional adaptation may not be beneficial to North Korean child refugees, especially given the prediction of Barker's theory. The lack of studies prevented a better understanding of this issue; therefore, large cohort studies, preferably with random sampling strategies, are needed to further understand this issue and to design appropriate interventions.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Dietary behaviors and nutritional status according to the bone mineral density status among adult female North Korean refugees in South Korea

Su-Hyeon Kim, Soo-Kyung Lee, Sin-Gon Kim

J Nutr Health. 2019;52(5):449-464. doi: 10.4163/jnh.2019.52.5.449.Comparative Analysis of Health Patterns and Gaps due to Environmental Influences in South Korea and North Korea, 2000–2017

Yoorim Bang, Jongmin Oh, Eun Mee Kim, Ji Hyen Lee, Minah Kang, Miju Kim, Seok Hyang Kim, Jae Jin Han, Hae Soon Kim, Oran Kwon, Hunjoo Ha, Harris Hyun-soo Kim, Hye Won Chung, Eunshil Kim, Young Ju Kim, Yuri Kim, Younhee Kang, Eunhee Ha

Ewha Med J. 2022;45(4):e14. doi: 10.12771/emj.2022.e14.

Reference

-

References

1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. World Food Programme. FAO/WFP crop and food security assessment mission to the democratic people’s republic of Korea [Internet]. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Food Programme;2011. November. [cited 2017 Jun 15]. Available from: http://documents.wfp.org.2. United Nations Children’s Fund. Situation analysis of children and women in Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – 2017 [Internet]. Pyongyang, DPR Korea: UNICEF;2016. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.3. United Nations Children’s Fund. Child malnutrition [Internet]. United Nations Children’s Fund. 2002. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.4. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of health and disease. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press;2006.5. World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children: a joint statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization Press;United Nations Children’s Fund;2009.6. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008; 371:340–57.

Article7. Adair LS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Stein AD, Martorell R, Ramirez-Zea M, et al. Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: findings from five birth cohort studies. Lancet. 2013; 382:525–34.

Article8. Gibson RS. Principles of nutritional assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press;2005.9. Muthayya S, Rah JH, Sugimoto JD, Roos FF, Kraemer K, Black RE. The global hidden hunger indices and maps: an advocacy tool for action. PLoS One. 2013; 12;8:e67860.

Article10. EU; United Nations Children's Fund; World Food Program. Nutrition survey of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Report by the EU, UNICEF and WFP of a study undertaken in collaboration with the Government to DPRK [Internet]. Pyongyang: United Nations Children’s Fund;1998. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.pwdigby.co.uk/pdf/Report_on_the_DPRK_Nutrition_Assessment_1998.pdf.11. Katona-Apte J, Mokdad A. Malnutrition of children in the Democratic People's Republic of North Korea. J Nutr. 1998; 128:1315–9.

Article12. DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics. Report of the Second Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2000 DPRK [Internet]. Pyongyang: DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics;2000. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/files/dprk.pdf.13. DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics. Report of the DPRK nutrition assessment [Internet]. Pyongyang: United Nations Children’s Fund;2002. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/dprk/nutrition_assessment.pdf.14. Hoffman DJ, Lee SK. The prevalence of wasting, but not stunting, has improved in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. J Nutr. 2005; 135:452–6.

Article15. DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics. DPRK 2004 Nutrition Assessment Report of Survey Results [Internet]. Pyongyang: DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics, Institute of Child Nutrition;2004. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/dprk/dprk_national_nutritionassessment_2004_final_report_07_03_05.pdf.16. DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics. DPR Korea multiple indicator cluster survey 2009, Final report [Internet]. Pyongyang: DPRK;2010; [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/dprk/MICS_DPRK_2009.pdf.17. United Nations Children’s Fund. Democratic People's Republic of Korea final report of the National Nutrition Survey 2012 [Internet]. Pyongyang: United Nations Children’s Fund;2012. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/eapro/DPRK_National_NutritionSurvey_2012.pdf.18. Kim JE. Nutritional state of children in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK): based on the DPRK final report of the National Nutrition Survey 2012. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2014; 17:135–9.

Article19. Schwekendiek D, Pak S. Recent growth of children in the two Koreas: a meta-analysis. Econ Hum Biol. 2009; 7:109–12.

Article20. Shim JE, Yoon J, Jeong SY, Park M, Lee YS. Status of early childhood and maternal nutrition in South Korea and North Korea. Korean J Comm Nutr. 2007; 12:123–32.21. Korea Center for Disease Control. Child and adolescent standard growth curve 2007 [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Center for Disease Control;2007. [cited 2017 Aug 20]. Available from: www.cdc.go.kr/.22. Korea Hana Foundation. Statistics [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Hana Foundation;2017. [cited 2017 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.koreahana.or.kr/intro/eGovHanaStat.jsp.23. Mi n i s t r y of R e u n i f i c at i on. Supp or t p o l i c i e s for North Korean refugees [Internet]. Seoul: Ministr y of Reunification;2017. [cited 2017 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/business/NKDefectorsPolicy/settlement/System/.24. Choi SK, Park SM, Joung H. Still life with less: North Korean young adult defectors in South Korea show continued poor nutrition and physique. Nutr Res Pract. 2010; 4:136–41.

Article25. Lee IS, Park HR, Kim YS, Park HJ. Physical and psychological health status of North Korean defector children. J Korean Acad Child Health Nurs. 2011; 17:256–263.

Article26. Lee SK, Nam SY, Hoffman D. Changes in nutritional status among displaced North Korean children living in South Korea. Ann Hum Biol. 2015; 42:581–4.

Article27. Pak S. The growth status of North Korean refugee children and adolescents from 6 to 19 years of age. Econ Hum Biol. 2010; 8:385–95.

Article28. Lee SK, Nam SY, Hoffman DJ. Growth retardation at early life and metabolic adaptation among North Korean children. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2015; 6:291–8.

Article29. Lee SK, Nam SY. Comparison of food and nutrient consumption status between displaced North Korean children in South Korea and South Korean children. Korean J Community Nutr. 2012; 17:407–418.

Article30. Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Korean nutrition society. dietary reference intakes for Koreans 2015. Sejong (Korea): Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016. p. 2–23.31. Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ. 1990; 301:1111.

Article32. World Health Organization. The double burden of malnutrition. Policy brief. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2017.33. 1,000 days. The Issue [Internet]. Washington: 1,000 days;2017. [cited 2017 Aug 11]. Available from: https://thousanddays.org/the-issue/.34. World Health Organization. E s s e nt i a l nut r it i on actions: improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition [Internet]. Geneva ( Sw it z e rl a n d ): WHO;2013. [ c it e d 2 0 1 7 Au g 1 1 ] . Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/84409/1/9789241505550_eng.pdf.35. Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008; 371:417–40.

Article36. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013; 382:452–77.

Article37. World Health Organization. Guideline: assessing and managing children at primary health-care facilities to prevent overweight and obesity in the context of the double burden of malnutrition. Updates for the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2017.38. Kirk SF, Penney TL, McHugh TL. Characterizing the obesogenic environment: the state of the evidence with directions for future research. Obes Rev. 2010; 11:109–17.

Article39. Lee SK, Sobal J, Frongillo EA Jr. Acculturation and health in Korean Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51:159–73.

Article40. Lee YH, Lee WJ, Kim YJ, Cho MJ, Kim JH, Lee YJ, et al. North Korean refugee health in South Korea (NORNS) study: study design and methods. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:172.

Article41. Schwekendiek D. Incorruptible information on North Korea? An overview and review of anthropometric assessment. Peace Unific. 2009; 1:317–64.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changes in health status of North Korean children and emerging health challenges of North Korean refugee children

- Comparison of the nutritional status of infants and young children in South Korea and North Korea

- Comparison of Food and Nutrient Consumption Status between Displaced North Korean Children in South Korea and South Korean Children

- Youth Sports

- North Korean Children's Health and the Role of Maternal and Child Health Experts