Ewha Med J.

2017 Oct;40(4):155-158. 10.12771/emj.2017.40.4.155.

Halo Nevus Arising from Congenital Melanocytic Nevus Featuring an Early Onset Vitiligo

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Dermatology, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. ashkwon@naver.com

- KMID: 2393719

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2017.40.4.155

Abstract

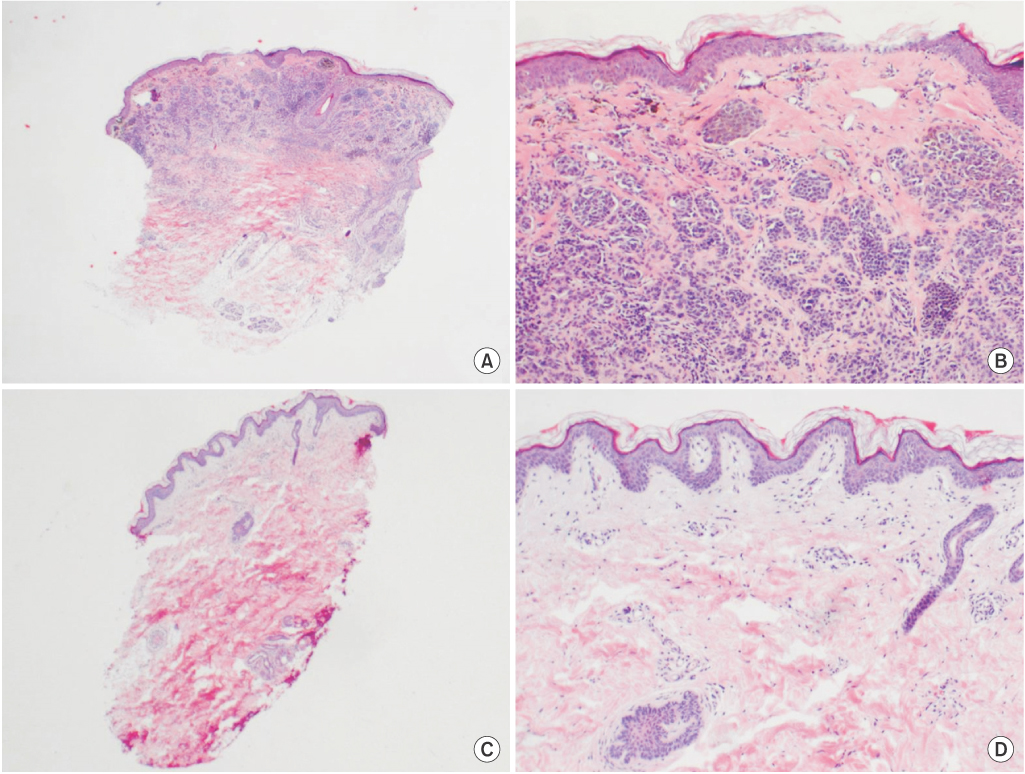

- Halo nevus and vitiligo are known to be associated with immunologic defect that result in typical skin lesions. Random shapes and sizes of whitish patches, depending on the type, are featured in vitiligo. Halo, on the other hand, presents by surrounding the previous pigmented lesion leaving a whitish-halo-like appearance. The mechanisms underlying these entities remain to be elucidated. Various immunological responses along with biomechanical activities suggest causal relationship between the two diseases. A 6-year-old male patient was recently presented with multiple whitish patches on the various parts of the body in a Koebner phenomenon manner. A noticeable hairy congenital melanocytic nevus surrounded a well-demarcated halo of depigmentation was also observed. Clinical and pathological findings were conclusive of as halo nevus with multiple concurrent vitiligo. The pathogenic relationship between the two entities must be underlined since the nature of disease progression is associated and the respective management may also be altered accordingly.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Taieb A, Picardo M. Clinical practice: vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:160–169.2. van den Boorn JG, Konijnenberg D, Dellemijn TA, van der Veen JP, Bos JD, Melief CJ, et al. Autoimmune destruction of skin melanocytes by perilesional T cells from vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2009; 129:2220–2232.3. Yang Y, Li S, Zhu G, Zhang Q, Wang G, Gao T, et al. A similar local immune and oxidative stress phenotype in vitiligo and halo nevus. J Dermatol Sci. 2017; 87:50–59.4. van Geel N, Van Poucke L, Van de Maele B, Speeckaert R. Relevance of congenital melanocytic naevi in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2015; 172:1052–1057.5. Handa S, Dogra S. Epidemiology of childhood vitiligo: a study of 625 patients from north India. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003; 20:207–210.6. Handa S, Kaur I. Vitiligo: clinical findings in 1436 patients. J Dermatol. 1999; 26:653–657.7. Suh KY, Bolognia JL. Signature nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 60:508–514.8. Barona MI, Arrunategui A, Falabella R, Alzate A. An epidemiologic case-control study in a population with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995; 33:621–625.9. Ezzedine K, Diallo A, Leaute-Labreze C, Seneschal J, Mossalayi D, AlGhamdi K, et al. Halo nevi association in nonsegmental vitiligo affects age at onset and depigmentation pattern. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:497–502.10. Nicolaidou E, Antoniou C, Miniati A, Lagogianni E, Matekovits A, Stratigos A, et al. Childhood- and later-onset vitiligo have diverse epidemiologic and clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 66:954–958.11. Zeff RA, Freitag A, Grin CM, Grant-Kels JM. The immune response in halo nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:620–624.12. Ogg GS, Rod Dunbar P, Romero P, Chen JL, Cerundolo V. High frequency of skin-homing melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in autoimmune vitiligo. J Exp Med. 1998; 188:1203–1208.13. Li S, Zhu G, Yang Y, Guo S, Dai W, Wang G, et al. Oxidative stress-induced chemokine production mediates CD8(+) T cell skin trafficking in vitiligo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2015; 17:32–33.14. Yu HS, Kao CH, Yu CL. Coexistence and relationship of antikeratinocyte and antimelanocyte antibodies in patients with non-segmental-type vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1993; 100:823–828.15. Workman M, Sawan K, El Amm C. Resolution and recurrence of vitiligo following excision of congenital melanocytic nevus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013; 30:e166–e168.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Halo Congenital Nevus Followed by Periocular Vitiligo

- Development of Halo Nevus Around Nevus Spilus as a Central Nevus, and the Concurrent Vitiligo

- Halo Congenital Nevus Associated with Extralesional Vitiligo

- A Case of Halo Congenital Nevus

- Two Cases of Congenital Giant Melanocytic Nevus (CGMN) with Vitiligo