J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc.

2016 Nov;55(4):310-320. 10.4306/jknpa.2016.55.4.310.

Conceptualization of Soliloquy in Patients with Schizophrenia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea. kys@snu.ac.kr

- 2Institute of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea.

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Eulji University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea.

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Keyo Hospital, Uiwang, Korea.

- KMID: 2361220

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2016.55.4.310

Abstract

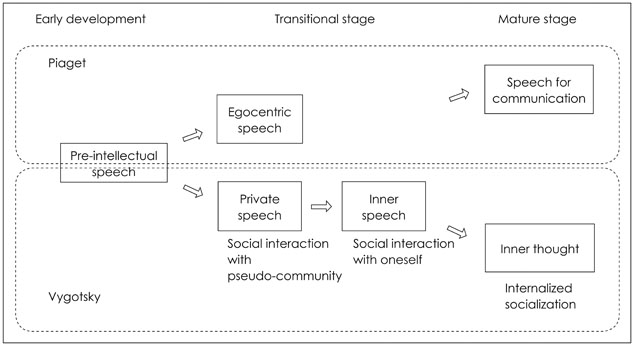

- Soliloquy is a significant symptom in schizophrenia and is usually regarded as being related to auditory hallucination. Elucidation of the psychopathology of soliloquy is incomplete. Soliloquy is also a normal human behavior that has multidimensional functions such as guiding internal cognitive processes and managing social interaction. In the young, soliloquy appears as egocentric speech and arises before maturation of the third-person perspective. Soliloquy has been regarded as indicative of an intermediary stage during the transformation of social speech into internalized thinking. Every thought process retains a social dimension because language itself is based on intersubjectively shared meanings, and internal thinking originates from interpersonal communication. Thus, soliloquy can be seen as a kind of thought process that accentuates the social dimension. This approach may help in understanding soliloquy in normal and pathological situations. Soliloquy was actively discussed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in European psychiatry. Since then it has received less attention and has been neglected as an academic concern, except in child developmental theory. Recently however, soliloquy has attracted more attention among neuroscientific researchers. To attain an advanced understanding of soliloquy, it is necessary to integrate the early European perception of soliloquy with current developmental theory. In this paper, we review past literature on the conceptualization of soliloquy and integrate those concepts into an explanatory framework. In addition, a case series and a discussion of the applicability of the explanatory framework are presented. Our results may help provide an insight into the contemporary understanding of soliloquy.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kobayashi T, Kato S. Hallucination of soliloquy: speaking component and hearing component of schizophrenic hallucinations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000; 54:531–536.

Article2. Grumet GW. On speaking to oneself. Psychiatry. 1985; 48:180–195.

Article3. DeLisi LE. Speech disorder in schizophrenia: review of the literature and exploration of its relation to the uniquely human capacity for language. Schizophr Bull. 2001; 27:481–496.

Article4. Hasegawa Y. Soliloquy for linguistic investigation. Stud Lang. 2011; 35:1–40.

Article5. The Compilation Committee of Oriental Medicine Dictionary. Oriental Medicine Dictionary. Seoul: JUNGDAM Publishing Company;2001.6. Tod D, Hardy J, Oliver E. Effects of self-talk: a systematic review. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011; 33:666–687.

Article7. Vocate DR. Intrapersonal communication: different voices, different minds. Hillsdale: Routledge;2012.8. Maher B. Schizophrenia, aberrant utterance and delusions of control: the disconnection of speech and thought, and the connection of experience and belief. Mind Lang. 2003; 18:1–22.

Article9. Chaika E. Thought disorder or speech disorder in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 1982; 8:587–594.10. Winsler A. Still talking to ourselves after all these years: a review of current research on private speech. In : Winsler A, Fernyhough C, Montero I, editors. Private speech, executive functioning, and the development of verbal self-regulation. New York: Cambridge University Press;2009. p. 3–41.11. Tecumseh Fitch W. The evolution of language. New York: Cambridge University Press;2010.12. Scherer KR. Speech and emotional states. In : Darby JK, editor. Speech evaluation in psychiatry. New York: Grune & Stratton;1981. p. 189–220.13. Jakobson R. Child language, aphasia and phonological universals. Hague: Walter de Gruyter;1980.14. Piaget J. The Language and Thought of the Child. London: Routledge;2001.15. Vygotskiĭ LS, Hanfmann E, Vakar G. Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press;2012.16. Berk LE, Winsler A. Scaffolding children's learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children;1995.17. Kendall PC, Treadwell KR. The role of self-statements as a mediator in treatment for youth with anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007; 75:380–389.

Article18. Meichenbaum D, Cameron R. Training schizophrenics to talk to themselves: a means of developing attentional controls. Behav Ther. 1973; 4:515–534.

Article19. de Guerrero MCM. Inner speech--L2: thinking words in a second language. New York: Springer Science & Business Media;2006.20. Weiskrantz L, Foundation F. Thought without language. Oxford: Clarendon Press;1988.21. Baars BJ. The conscious access hypothesis: origins and recent evidence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002; 6:47–52.

Article22. Morin A. Possible links between self-awareness and inner speech theoretical background, underlying mechanisms, and empirical evidence. J Conscious Stud. 2005; 12:115–134.23. Alderson-Day B, Fernyhough C. Inner speech: development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology. Psychol Bull. 2015; 141:931–965.

Article24. Fernyhough C, Fradley E. Private speech on an executive task: relations with task difficulty and task performance. Cogn Dev. 2005; 20:103–120.

Article25. Perrone-Bertolotti M, Rapin L, Lachaux JP, Baciu M, Loevenbruck H. What is that little voice inside my head? Inner speech phenomenology, its role in cognitive performance, and its relation to self-monitoring. Behav Brain Res. 2014; 261:220–239.

Article26. Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. In : Aschaffenburg G, editor. Handbuch der Psychiatrie. Leipzig: Deuticke;1911.27. Irarrázaval L. The lived body in schizophrenia: transition from basic self-disorders to full-blown psychosis. Front Psychiatry. 2015; 6:9.28. Hansen CF, Torgalsbøen AK, Melle I, Bell MD. Passive/apathetic social withdrawal and active social avoidance in schizophrenia: difference in underlying psychological processes. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009; 197:274–277.

Article29. Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015; 16:620–631.

Article30. Torres A, Olivares JM, Rodriguez A, Vaamonde A, Berrios GE. An analysis of the cognitive deficit of schizophrenia based on the Piaget developmental theory. Compr Psychiatry. 2007; 48:376–379.

Article31. Miller R. Vygotsky in Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press;2011.32. Allen P, Amaro E, Fu CH, Williams SC, Brammer MJ, Johns LC, et al. Neural correlates of the misattribution of speech in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007; 190:162–169.33. Woodward TS, Menon M, Whitman JC. Source monitoring biases and auditory hallucinations. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2007; 12:477–494.

Article34. Ey H. Traité des Hallucinations. Paris: Masson;1973.35. Jardri R, Cachia A, Thomas P, Pins D. The Neuroscience of Hallucinations. New York: Springer Science & Business Media;2012.36. Larøi F, de Haan S, Jones S, Raballo A. Auditory verbal hallucinations: dialoguing between the cognitive sciences and phenomenology. Phenomenol Cogn Sci. 2010; 9:225–240.

Article37. 古川健三 . 精神分裂病に於ける獨語症状. 精神經誌. 1949; 51:61–66.38. Jeong SH, Son JW, Kim YS. Understanding of “attunement disorder” from phenomenological-anthropological perspective: inquiry into the use of the term “attunement” in psychiatric literature. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2013; 52:279–291.

Article39. Ogura H. [A study on monologue symptoms]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 1965; 67:1187–1196.40. Stanghellini G, Cutting J. Auditory verbal hallucinations--breaking the silence of inner dialogue. Psychopathology. 2003; 36:120–128.

Article41. Puchalska-Wasyl MM. The functions of internal dialogs and their connection with personality. Scand J Psychol. 2016; 57:162–168.

Article42. Pérez-Alvarez M, García-Montes JM, Perona-Garcelán S, Vallina-Fernández O. Changing relationship with voices: new therapeutic perspectives for treating hallucinations. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008; 15:75–85.

Article43. Cameron N. The paranoid pseudo-community revisited. Am J Sociol. 1959; 65:52–58.

Article44. Schultze-Lutter F. Subjective symptoms of schizophrenia in research and the clinic: the basic symptom concept. Schizophr Bull. 2009; 35:5–8.

Article45. Moreira-Almeida A. Research on mediumship and the mind-brain relationship. In : Moreira-Almeida A, Santos FS, editors. Exploring frontiers of the mind-brain relationship. New York: Springer Science & Business Media;2011. p. 191–214.46. McCarthy-Jones S. Hearing voices: the histories, causes and meanings of auditory verbal hallucinations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;2012.47. Leudar I, Thomas P. Voices of reason, voices of insanity: studies of verbal hallucinations. London: Routledge;2000.48. Kasahara Y, Fujinawa A, Sekiguchi H, Matsumoto M. Fear of eye-to-eye confrontation and fear of emitting bad odors (in Japanese). Tokyo: Igaku Shoin;1972.