J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2014 Jul;55(7):1106-1110.

Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection for the Treatment of Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Candida Chorioretinitis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Hanyang University Medical Center, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. stynel@nate.com

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report a case of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to candida chorioretinitis initially treated with an intravitreal bevacizumab injection.

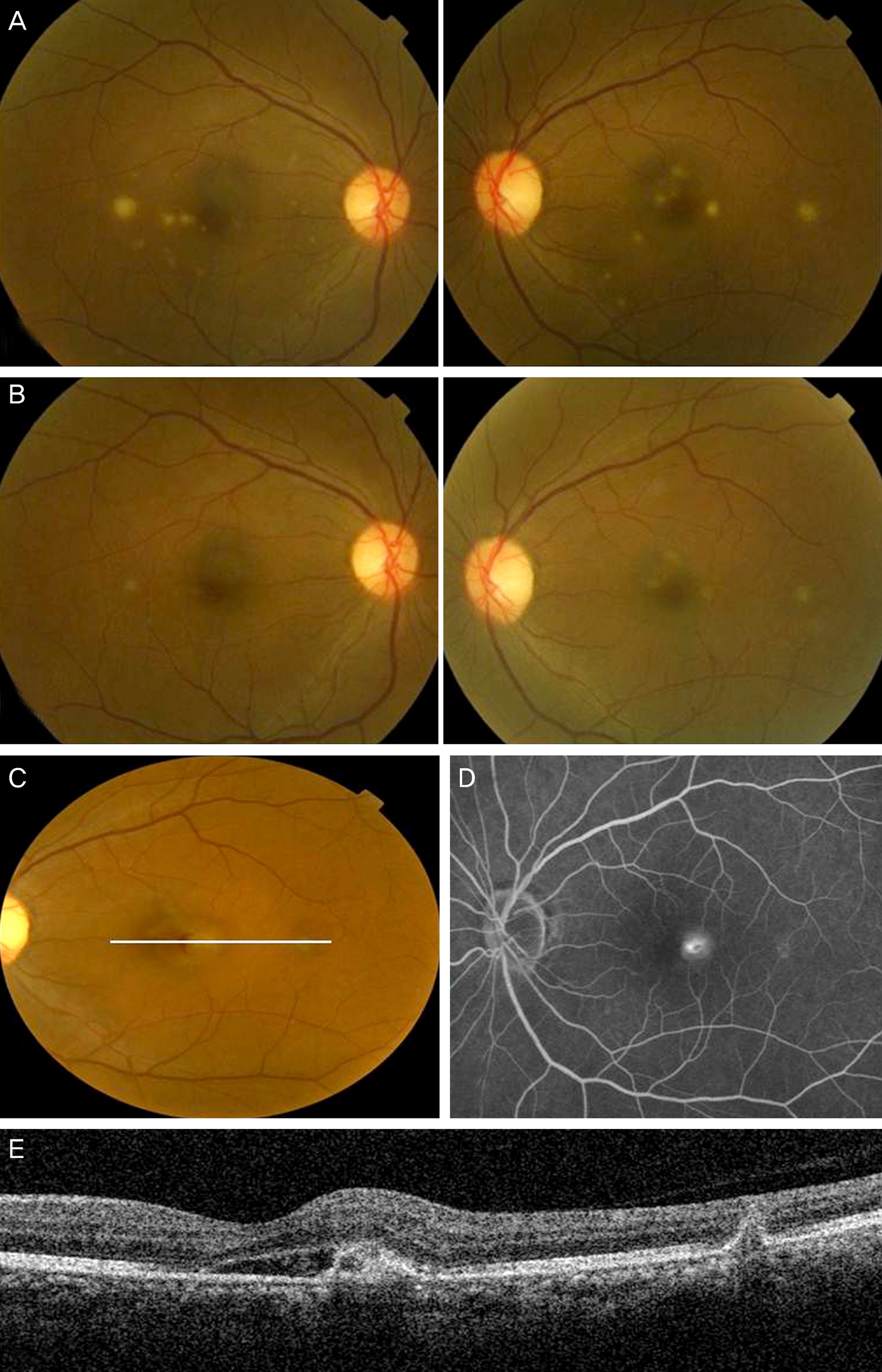

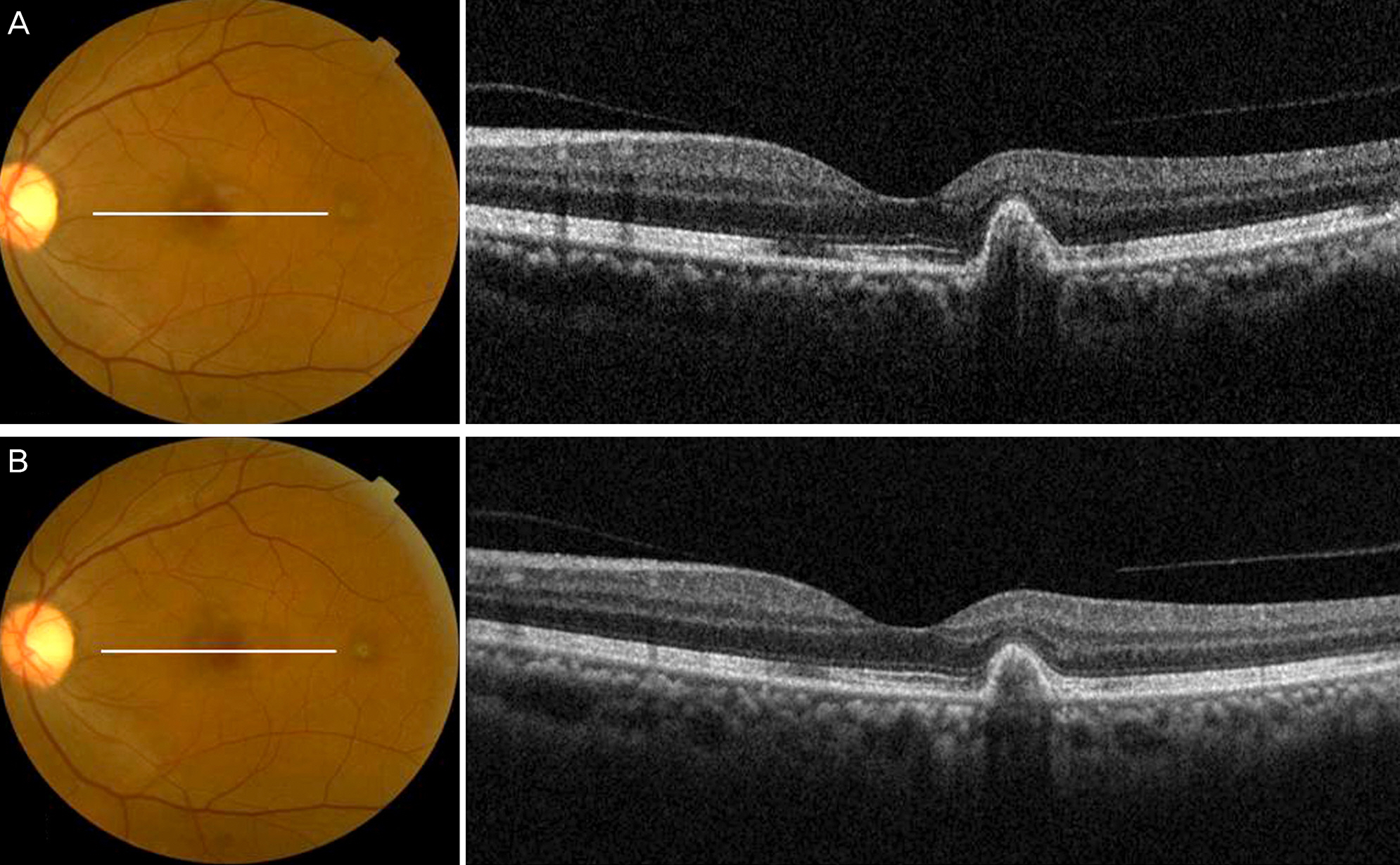

CASE SUMMARY

A 50-year-old female presented at our clinic with decreased vision and metamorphopsia in her left eye of 5 days duration. She received an anti-fungal treatment 2 months prior due to the presence of endogenous candida choroiditis in both eyes. Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed juxtafoveal CNV in her left eye. Three monthly intravitreal injections of bevacizumab were administered as the initial loading dosage. Her visual symptoms improved and CNV regression was observed on OCT. No recurrence or complications were observed during the 6 month follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the present study results we suggest that intravitreal bevacizumab injection can be used to effectively treat CNV and improve visual symptoms during the treatment of juxtafoveal CNV associated with candida choroiditis.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Jampol LM, Sung J, Walker JD, et al. Choroidal neovascularization secondary to Candida albicans chorioretinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996; 121:643–9.

Article2. Beebe WE, Kirkland C, Price J. A subretinal neovascular membrane as a complication of endogenous Candida endophthalmitis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987; 19:207–9.3. Tedeschi M, Varano M, Schiano Lomoriello D, et al. Photodynamic therapy outcomes in a case of macular choroidal neovascularization secondary to Candida endophthalmitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007; 17:124–7.

Article4. CATT Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neo- vascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:1897–908.5. Ruiz-Moreno JM, Montero JA. Intravitreal bevacizumab to treat myopic choroidal neovascularization: 2-year outcome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010; 248:937–41.

Article6. Julian K, Terrada C, Fardeau C, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab as first local treatment for uveitis-related choroidal neovascularization: long-term results. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011; 89:179–84.7. Ehrlich R, Ciulla TA, Maturi R, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Retina. 2009; 29:1418–23.

Article8. Schadlu R, Blinder KJ, Shah GK, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization in ocular histoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 145:875–8.

Article9. Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009; 148:43–58.e1.

Article10. Sheu SJ. Intravitreal ranibizumab for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to endogenous endophthalmitis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009; 25:617–21.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of High-dose Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection on Refractory Idiopathic Choroidal Neovasculariz

- Multifocal Electroretinogram Findings after Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection in Choroidal Neovascularization of Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- A Case of Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection for the Treatment of Choroidal Neovascularization in Morning Glory Syndrome

- Long-term Therapeutic Effect of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) on Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization

- Choroidal Neovascularization in a Patient with Best Disease