J Nutr Health.

2013 Oct;46(5):447-460.

Dietary maximum exposure assessment of vitamins and minerals from various sources in Korean adolescents

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Home Economics Education, Graduate School of Kongju National University, Gongju 314-701, Korea.

- 2Department of Food Science & Nutrition, Dongseo University, Busan 617-716, Korea.

- 3Department of Technology and Home Economics Education, Kongju National University, Gongju 314-701, Korea. shkim@kongju.ac.kr

Abstract

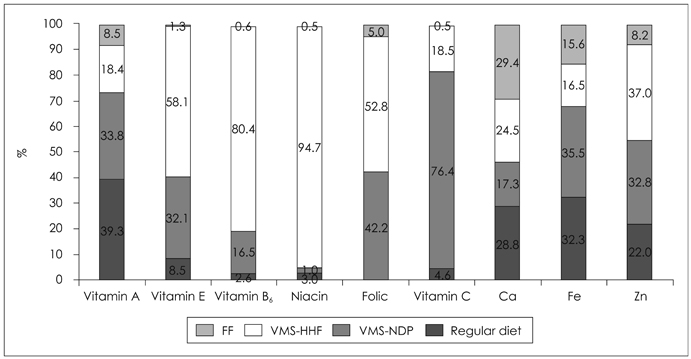

- Dietary supplement use is prevalent and represents an important source of nutrition. This study was conducted in order to assess the dietary maximum exposure of vitamins and minerals from various sources including regular diet, vitamin.mineral supplements for non-prescription drug (VMS-NPD), vitamin.mineral supplements for health functional foods (VMS-HFF), and fortified foods (FF). A total of 1,407 adolescent boys and girls attending middle or high schools were chosen from various cities and rural communities in Korea. Users of vitamin and mineral supplements (n = 60, 15-18 years of age) were chosen from the above 1,407 students. Intake of vitamins and minerals from a regular diet and FF was assessed by both food record method and direct interview for three days of two weekdays and one weekend, and those from VMS-NPD and VMS-HFF were assessed by both questionnaire and direct interview, and compared with the recommended nutrient intake (RNI) and the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for Korean adolescents. Daily average exposure range of vitamins and minerals from a regular diet was 0.3 to 4.4 times of the RNI. Some subjects had an excessive exposure to the UL in the following areas: from regular diets, vitamin A (1.7%) and niacin (5.0%); from only VMS-NPD, vitamin C (9.1%) and iron (5.6%); and from only VMS-HFF, niacin (8.6%) > vitamin B6 (7.5%) > folic acid (2.9%) > vitamin C (2.3%). Nutrients of daily total intake from regular diet, VMS-NPD, VMS-HFF, and FF higher than the UL included nicotinic acid for 33.3% of subjects, and, then, in order, vitamin C (26.6%) > vitamin A (13.3%), iron (13.3%) > zinc (11.7%) > calcium (5.0%) > vitamin E (1.7%), vitamin B6 (1.7%). Thus, findings of this study showed that subjects may potentially be at risk due to overuse of supplements, even though most of them took enough vitamins and minerals from their regular diet. Therefore, we should encourage adolescents to have sound health care habits through systematic and educational aspects.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adolescent*

Ascorbic Acid

Calcium

Delivery of Health Care

Diet

Dietary Supplements

Folic Acid

Food, Fortified

Functional Food

Humans

Iron

Korea

Minerals*

Niacin

Surveys and Questionnaires

Rural Population

Vitamin A

Vitamin B 6

Vitamin E

Vitamins*

Zinc

Ascorbic Acid

Calcium

Folic Acid

Iron

Minerals

Niacin

Vitamin A

Vitamin B 6

Vitamin E

Vitamins

Zinc

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, Betz JM, Sempos CT, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J Nutr. 2011; 141(2):261–266.

Article2. Block G, Jensen CD, Norkus EP, Dalvi TB, Wong LG, McManus JF, Hudes ML. Usage patterns, health, and nutritional status of long-term multiple dietary supplement users: a cross-sectional study. Nutr J. 2007; 6:30.

Article3. Kim SH, Han JH, Kim WY. Health functional food use and related variables among the middle-aged in Korea. Korean J Nutr. 2010; 43(3):294–303.

Article4. Kim SH, Lee SH, Hwang YJ, Kim WY. Exposure assessment of vitamins and minerals from various sources of Koreans. Korean J Nutr. 2006; 39(6):539–548.5. Murphy SP, White KK, Park SY, Sharma S. Multivitamin-multimineral supplements' effect on total nutrient intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 85(1):280S–284S.6. Han JH, Kim SH. Behaviors of vitamin, mineral supplement usage by healthy adolescents attending general middle or high schools in Korean. Korean J Nutr. 2000; 33(3):332–342.7. Merkel JM, Crockett SJ, Mullis R. Vitamin and mineral supplement use by women with school-age children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990; 90(3):426–428.

Article8. Walter P. Towards ensuring the safety of vitamins and minerals. Toxicol Lett. 2001; 120(1-3):83–87.

Article9. Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV, Lin CT. Dietary supplements in a national survey: prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106(12):1966–1974.

Article10. Yang JK, Kim SH. Patterns of fortified food use among teenagers in Chungnam province and Daejeon city in Korea. Korean J Food Cult. 2004; 19(4):447–459.11. Brown A. Chemistry of food composition. In : Brown A, editor. Understanding Food: Principles and Preparation. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth;2000. p. 43–46.12. Han JH, Kim SH. Vitamin, mineral supplement use and related variables by Korean adolescents. Korean J Nutr. 1999; 32(3):268–276.13. Kim SH, Keen CL. Patterns of vitamin/mineral supplement usage by adolescents attending athletic high schools in Korea. Int J Sport Nutr. 1999; 9(4):391–405.

Article14. Kim SH, Keen CL. Vitamin and mineral supplement use among children attending elementary schools in Korea: a survey of eating habits and dietary consequences. Nutr Res. 2002; 22(4):433–448.

Article15. Kim SH, Han JH, Hwang YJ, Kim WY. Use of functional foods for health by 14-18 year old students attending general junior or senior high schools in Korea. Korean J Nutr. 2005; 38(10):864–872.16. Kim SH, Han JH, Zhu QY, Keen CL. Use of vitamins, minerals, and other dietary supplements by 17- and 18-year-old students in Korea. J Med Food. 2003; 6(1):27–42.

Article17. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary reference intakes for Koreans. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society;2005.18. Yakup Newspaper. Korean drug index. Seoul: Yakup Newspaper;2009.19. Budarari S, O'Neil MJ, Smith A, Heckslman PE. The Merck Index: an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs and biologicals. 11th edition. Rahway (NJ): Merck & Co.;1989.20. David WH, Peter AM, Victer WR, Daryl KG. Harpe's review of biochemistry. 30th edition. Los Altos (CA): Lange Medical Publications;1995.21. Korea Food and Drug Administration. Tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins and minerals in functional foods for health (II). Seoul: Korea Food and Drug Administration;2005.22. National Rural Living Science Institute (KR). Food composition. Suwon: National Rural Living Science Institute;2001.23. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary reference intakes for Koreans. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society;2010.24. Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals (UK). Safe upper levels for vitamins and minerals. London: Food Standard Agency;2003. p. 52–61.25. Institute of Medicine (US). Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press;2000.26. Institute of Medicine (US). Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin D, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press;2001.27. Rock CL. Multivitamin-multimineral supplements: who uses them? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 85(1):277S–279S.

Article28. Stang J, Story MT, Harnack L, Neumark-Sztainer D. Relationships between vitamin and mineral supplement use, dietary intake, and dietary adequacy among adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000; 100(8):905–910.

Article29. Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 160(4):339–349.

Article30. Fulgoni VL 3rd, Keast DR, Bailey RL, Dwyer J. Foods, fortificants, and supplements: Where do Americans get their nutrients? J Nutr. 2011; 141(10):1847–1854.

Article31. Butte NF, Fox MK, Briefel RR, Siega-Riz AM, Dwyer JT, Deming DM, Reidy KC. Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and preschoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010; 110:12 Suppl. S27–S37.

Article32. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Industry Development Institute. In-Depth Analysis on the 3rd (2005) Korea Health and Nutrition Examination Survey -Nutrition Survey-. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2007. p. 341–343.33. Kloosterman J, Fransen HP, de Stoppelaar J, Verhagen H, Rompelberg C. Safe addition of vitamins and minerals to foods: setting maximum levels for fortification in the Netherlands. Eur J Nutr. 2007; 46(4):220–229.

Article34. Verkaik-Kloosterman J, McCann MT, Hoekstra J, Verhagen H. Vitamins and minerals: issues associated with too low and too high population intakes. Food Nutr Res. 2012; 56:5728.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Exposure Assessment of Vitamins and Minerals from Various Sources of Koreans

- Effects of Antioxidant Vitamins & Minerals Supplementation on Blood Pressure and Lipids in the Elderly with Hypertension

- Nutrient Composition and Content of Vitamin and Mineral Supplements and Their Appropriateness for Pregnant and Lactating Women in Korea

- A Study on Dietary Intake Behavior of Behçet's Disease Patients

- Diabetes and Nuts