Tuberc Respir Dis.

2011 Apr;70(4):293-300.

Early Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Kang-Dong Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea.

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 8Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 9Department of Internal Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 10Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. sdlee@amc.seoul.kr

- 11Department of Internal Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 12Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 13Department of Internal Medicine, Wonkwang University Sanbon Hospital, Wonkwang University College of Medicine, Gunpo, Korea.

- 14Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 15Department of Internal Medicine, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, Uijeongbu, Korea.

- 16Department of Internal Medicine, Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Abstract

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a substantially under-diagnosed disorder, and the diagnosis is usually delayed until the disease is advanced. However, the benefit of early diagnosis is not yet clear, and there are no guidelines in Korea for doing early diagnosis. This review highlights several issues regarding early diagnosis of COPD. On the basis of several lines of evidence, early diagnosis seems quite necessary and beneficial to patients. Early diagnosis can be approached by several methods, but it should be confirmed by quality-controlled spirometry. Compared with its potential benefit, the adverse effects of spirometry or pharmacotherapy appear relatively small. Although it is difficult to evaluate the benefit of early diagnosis by well-designed trials, several lines of evidence suggest that we should try to diagnose and manage patients with COPD at early stages of the disease.

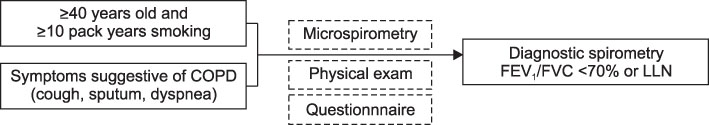

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, Mathers CD, Hansell AL, Held LS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006. 27:397–412.2. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006. 3:e442.3. Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, Chang JH, Lim CM, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 172:842–847.4. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2008). 2008. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.5. Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, Muiño A, Lopez MV, Valdivia G, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet. 2005. 366:1875–1881.6. Peña VS, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, Jiménez-Ruiz CA, Villasante C, Masa JF, et al. Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest. 2000. 118:981–989.7. Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007. 370:765–773.8. Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Lam YM, O'Donnell DE. Mechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. 177:622–629.9. Ferrer M, Alonso J, Morera J, Marrades RM, Khalaf A, Aguar MC, et al. The Quality of Life of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study Group. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1997. 127:1072–1079.10. Mannino DM, Doherty DE, Sonia Buist A. Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Respir Med. 2006. 100:115–122.11. Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S, Langer D, Valluri SR, Martino L, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med. 2010. 104:1005–1011.12. Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010. 363:1128–1138.13. Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PM, Pride NB, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects' perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002. 20:799–805.14. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007. 176:532–555.15. Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Sherif K, Wilt TJ, Weinberger S, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007. 147:633–638.16. Lin K, Watkins B, Johnson T, Rodriguez JA, Barton MB. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008. 148:535–543.17. Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009. 374:733–743.18. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000. 160:1683–1689.19. Badgett RG, Tanaka DJ, Hunt DK, Jelley MJ, Feinberg LE, Steiner JF, et al. Can moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease be diagnosed by historical and physical findings alone? Am J Med. 1993. 94:188–196.20. Mannino DM, Etzel RA, Flanders WD. Do the medical history and physical examination predict low lung function? Arch Intern Med. 1993. 153:1892–1897.21. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD [Internet]. Version 1.2. 2004. cited 2010 Nov 8. New York: American Thoracic Society;[updated 2005 September 8]. Available from: http://www.thoracic.org/go/copd.22. Johannessen A, Lehmann S, Omenaas ER, Eide GE, Bakke PS, Gulsvik A. Post-bronchodilator spirometry reference values in adults and implications for disease management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006. 173:1316–1325.23. Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, Pedersen OF, Crapo RO, Miller MR, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax. 2008. 63:1046–1051.24. Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005. 58:230–242.25. Parkes G, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Dent R. Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2quit randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008. 336:598–600.26. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:775–789.27. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008. 359:1543–1554.28. Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Calverley PM, Celli B, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, et al. Efficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH study. Respir Res. 2009. 10:59.29. Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Tashkin DP, et al. Effect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009. 374:1171–1178.30. Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J, Von Sternberg T. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994. 331:778–784.31. Jackson LA, Neuzil KM, Yu O, Benson P, Barlow WE, Adams AL, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2003. 348:1747–1755.32. Nichol KL, Baken L, Wuorenma J, Nelson A. The health and economic benefits associated with pneumococcal vaccination of elderly persons with chronic lung disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999. 159:2437–2442.33. Alfageme I, Vazquez R, Reyes N, Muñoz J, Fernández A, Hernandez M, et al. Clinical efficacy of anti-pneumococcal vaccination in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2006. 61:189–195.34. Fields CL, Byrd RP Jr, Ossorio MA, Roy TM, Michaels MJ, Vogel RL. Cardiac arrhythmias during performance of the flow-volume loop. Chest. 1993. 103:1006–1009.35. Hardie JA, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Ellingsen I, Bakke PS, Mørkve O. Risk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur Respir J. 2002. 20:1117–1122.36. Vedal S, Crapo RO. False positive rates of multiple pulmonary function tests in healthy subjects. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1983. 19:263–266.37. Strassels SA, Smith DH, Sullivan SD, Mahajan PS. The costs of treating COPD in the United States. Chest. 2001. 119:344–352.38. van den Boom G, van Schayck CP, van Möllen MP, Tirimanna PR, den Otter JJ, van Grunsven PM, et al. Active detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in the general population. Results and economic consequences of the DIMCA program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. 158:1730–1738.39. Feenstra TL, van Genugten ML, Hoogenveen RT, Wouters EF, Rutten-van Mölken MP. The impact of aging and smoking on the future burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a model analysis in the Netherlands. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 164:590–596.40. Dal Negro R. Optimizing economic outcomes in the management of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008. 3:1–10.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Reducing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in Korea: early diagnosis matters

- Strategies for Management of the Early Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- Cor Pulmonale with Particular Reference to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Respiratory Review of 2014