Nutr Res Pract.

2008 Sep;2(3):165-170.

Protein and hematological evaluations of infant formulated from cooking banana fruits (Musa spp, ABB genome) and fermented bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean L. Verdc) seeds

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. soijarotimi2000@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

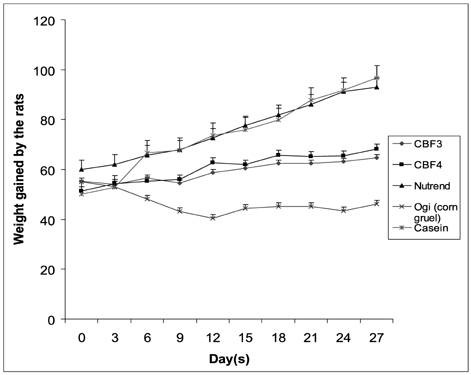

- Protein-energy malnutrition is regarded as one of the public health problems in developing countries as a result of poor feeding practices due to poverty. This study, therefore, aimed at evaluating nutritional quality of a potential weaning food formulated from locally available food materials. The cooking banana fruit (CB) and bambara groundnut seeds (BG) were purchased from local market in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. The CB and BG were processed into flours, mixed in ratios of 90:10, 80:20, 70:30 and 60:40 and subjected into proximate, sensory and biochemical analyses using standard procedures. Nutrend (a commercial formula) and ogi (corn gruel, a traditional weaning food) were used as control. The nutritient composition (g/100 g) of the food samples were ranged as follows: moisture 2.94-6.94, protein 7.02-16.0, ash 1.76-2.99, fat 0.76-8.45, fibre 1.52-3.75, carbohydrate 63.84-88.43 and energy 1569.8-1665.7 kcal. The biological value (BV), net protein retention (NPR), protein efficiency ratio (PER) and feed efficiency ratio (FER) of the experimental food samples were significantly (p<0.05) lower than nutrend, but higher than ogi. The haematological variables of rats fed with formulated food samples, commercial formula (nutrend) and traditional weaning food (ogi) were not significantly (p>0.05) influenced by the dietary treatment. However, the values obtained for red blood cell (RBC), white blood cell (WBC), pack cell volume (PCV) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were higher in the experimental food samples than the commercial food. The growth rate of animals fed with experimental food samples were lower than those fed with the nutrend, but higher than those fed with ogi. In conclusion, the nutritional quality of CB and fermented BG mix of 60:40 ratio was better than ogi; and comparable to the nutrend. This implies that it can be used to replace low quality traditional weaning food and the expensive commercial weaning formula.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Akpapunam MA, Sefa-Dedeh S. Traditional lactic acid fermentation, malt addition and quality development in maize-cowpea weaning blends. Food Nutr Bull. 1995. 16:75–80.

Article2. AOAC. Hortwitz W, editor. The Association of official analytical chemists. 1990. 13th Edition. Washington, D.C. USA: AOAC;858.3. Brabin BJ, Coulter JBS. Cook GC, Zumla AI, editors. Nutrition-associated disease. Manson's tropical diseases. 2003. London. UK: Saunders;561–580.

Article4. Brough SH, Azam-Ali SN, Taylor AJ. The potential of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) in vegetable milk production and basic protein functionality systems. Food Chem. 1993. 47:277–283.

Article5. Dewey KG, Brown KH. Update on Technical Issues Concerning Complementary Feeding of Young Children in Developing Countries and Implications for Intervention Programs. Food Nutr Bull. 2003. 24:5–28.

Article6. Duncan T. CMH working papers no WG1:7. Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Health, nutrition and economic prosperity: a microeconomic perspective. 2001. Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organization.7. FAO. Undernourishmentaround the world. The state of food insecurity in the World 2004. 2004. Rome:8. Guiro AT, Sail MG, Kane O, Ndiaye AM, Diarra D, Sy MTA. Protein-calorie malnutrition in Senegalese children. Effects of rehabilitation with a pearl millet weaning food. Nutr Rep Int. 1987. 36:1071–1079.9. Ijarotimi OS. Evaluation of nutritional quality and sensory attributes of home made processed complementary diet from locally available food materials (Sorghum biclor and Sphenostylis stenocarpa). Journal of Food Technology. 2006. 4:334–338.10. Ijarotimi OS, Aroge F. Evaluation of nutritional composition, sensory and physical properties of a potential weaning food from locally available food materials-Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) and soybeans (Glycine max). Polish Journal of Food and Nutritional Sciences. 2005. 14:411–415.11. Ijarotimi OS, Bakare SS. Evaluation of proximate, mineral and antinutritional factor of homemade processed complementary diet from locally available food materials (Sorghum biclor and Sphenostylis stenocarpa). Journal of Food Technology. 2006. 4:339–344.12. Ijarotimi OS, Ashipa F. Evaluation of nutritional composition, sensory and physical property of home processed weaning food based on low cost locally available food materilas. Nutrition and Food Science. 2006. 36:6–17.

Article13. Ikujenlola VA, Fashakin JB. The physicochemical properties of a complementary diet prepared from vegetable proteins. Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment. 2005. 3:23–26.14. Khan AR. Macroeconomic Policies and Poverty: An Analysis based on the Experience in Ten Asian Countries. Paper presented at the ILO Asian Regional Policy Workshop on Poverty Alleviation, 5-7. 1997.15. Krebs NF, Westcott J. Zinc and Breastfed Infants: If and When Is There a Risk of Deficiency? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002. 503:69–75.

Article16. Lamb GN. Manual of Veterinary Laboratory Techniques. 1981. CIBAGEIGY: Nairobi. Kenya;96–97.17. Levin HM, Pollitt E, Galloway R, McGuire J. Jamison DT, Mosley WH, Measham AR, Bobadilla JL, editors. Micronutrient deficiency disorders. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 1993. 2nd ed. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press;421–451.18. Mbata TI, kenebomeh MJ, Ahonkhai I. Nutritional status of maize fermented meal by fortification with bambara-nut. African Journal of Food Agriculture Nutrition and Development. 2007. 7.

Article19. Mensa-Wilmot Y, Phillips RD, Sefa-Dedeh S. Acceptability of extrusion cooked cereal/legume weaning food supplements to Ghanaian mothers. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2001. 52:83–90.20. Michaelsen KF, Friis H. Complementary feeding: a global perspective. Nutr. 1998. 14:763–766.

Article21. Millward DJ, Jackson AA. Protein/energy ratios of current diets in developed and developing countries compared with a safe protein/energy ratio: implications for recommended protein and amino acid intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2004. 7:387–405.

Article22. Neumann C, Harris DM, Rogers LM. Contribution of Animal Source Foods in Improving Diet Quality and Function in Children in the Developing World. Nutr Res. 2002. 22:193–220.

Article23. Obizoba IC. Nutritive value of cowpea-bambara groundnut-rice mixtures in adult rats. Nutr Rep Int. 1983. 27:709–712.24. Oliveira JS. Grain legumes of Mozambique. Tropical Grain Legume Bulletin. 1976. 3:13–15.25. Oluyemi JA, Fetuga BL, Endeley HNL. The metabolizable energy value of some feed ingredients for young chicks. Poult Sci. 1976. 55:611–618.

Article26. Onilude AA, Sanni AI, Ighalo MI. Effect of process improvement on the physico-chemical properties of infant weaning food from fermented composite blends of cereal and soybeans. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1999. 54:239–250.27. Osmani SR. Poverty and Nutrition in South Asia. Abraham Horwitz lecture delivered at the Symposium on Nutrition and Poverty held on the occasion of UN ACC/SCN 24th Session. 1997. Kathmandu. Nepal: 17–21.28. Pinstrup-Andersen P, Burger S, Habicht JP, Peterson K. Jamison DT, Mosley WH, Measham AR, Bobadilla JL, editors. Protein-energy malnutrition. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 1993. 2nd ed. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press;391–420.29. Sachs JD, McArthur JW. The Millennium Project: a plan for meeting the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2005. 365:347–353.

Article30. Schofield C, Ashworth A. Why have mortality rates for severe malnutrition remained so high? Bull World Health Organ. 1996. 74:223–229.31. Swennen R. Plantain Cultivation under West African Condition. A Reference Manual. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). 1990. Ibadan. Nigeria: 1–24.32. Uwaegbute AC, Nnanyelugo DO. Nutritive value and biological evaluation of processed cowpea diets compared with local weaning foods in Nigeria. Nutr Rep Int. 1987. 36:119–129.33. WHO/UNICEF. WHO/NUT/98.1. Complementary Feeding of Young Children in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Scientific Knowledge. 1998. Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organization;1–228.34. WHO. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (A54/INF.DOC./4). 2001. Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organization;1–5.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Protein quality, hematological properties and nutritional status of albino rats fed complementary foods with fermented popcorn, African locust bean, and bambara groundnut flour blends

- Development of Molecular Markers to Detect Diaporthe spp. from Decayed Soybean Seeds

- A Case of Latex-fruit Syndrome in a Patient with Latex Anaphylaxis

- Evaluation of Banana Hypersensitivity Among a Group of Atopic Egyptian Children: Relation to Parental/Self Reports

- Banana anaphylaxis in Thailand: case series