Lab Med Online.

2015 Jan;5(1):33-37. 10.3343/lmo.2015.5.1.33.

A Case of Plasmodium malariae Infection Imported from Guinea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Health Science, Dankook University Graduate School, Cheonan, Korea.

- 2Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, Ansan University, Ansan, Korea.

- 3Department of Malaria and Parasitic Disease, National Institutes of Health, Cheongju, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea. jyjasmine@catholic.ac.kr

- KMID: 2312265

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/lmo.2015.5.1.33

Abstract

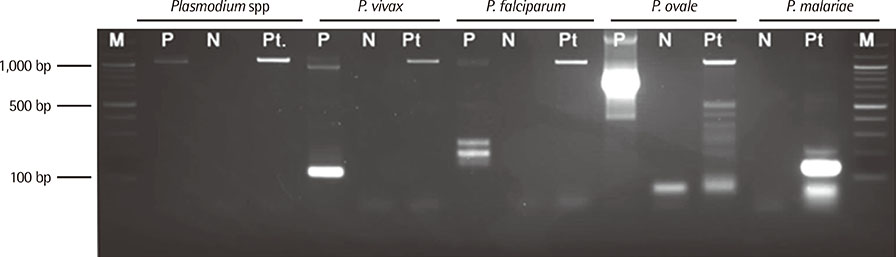

- Recently, the number of Korean travelers and workers to malaria-endemic regions has increased, and the number of patients with imported malaria cases has increased as well. In Korea, most cases of imported malaria infections are caused by Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Only one report of imported P. malariae infection has been published thus far. Here, we describe a case of imported P. malariae infection that was confirmed by peripheral blood smear and nested PCR targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene. A 53-yr-old man, who had stayed in the Republic of Guinea in tropical West Africa for about 40 days, experienced fever and headache for 3 days before admission. The results of rapid malaria test using the SD Malaria Antigen/Antibody Kit (Standard Diagnostics, Korea) were negative, but Wright-Giemsa stained peripheral blood smear revealed Plasmodium. To identify the Plasmodium species and to examine if the patient had a mixed infection, we performed nested PCR targeting the SSU rRNA gene. P. malariae single infection was confirmed by nested PCR. Sequence analysis of the SSU rRNA gene of P. malariae showed that the isolated P. malariae was P. malariae type 2. Thus, our findings suggest that when cases of imported malaria infection are suspected, infection with P. malariae as well as P. falciparum and P. vivax should be considered. For the accurate diagnosis and treatment of imported malaria cases, we should confirm infection with Plasmodium species by PCR as well as peripheral blood smear and rapid malaria antigen test.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Krotoski WA, Garnham PC, Bray RS, Krotoski DM, Killick-Kendrick R, Draper CC, et al. Observations on early and late post-sporozoite tissue stages in primate malaria. I. Discovery of a new latent form of Plasmodium cynomolgi (the hypnozoite), and failure to detect hepatic forms within the first 24 hours after infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982; 31:24–35.

Article2. Song HS, Kim JY, Na DG, Kim JY, Kim YJ, Yeom JS, et al. The first case of Plasmodium malariae infection imported from Nigeria to Korea. Korean J Med. 2009; 77:S1323–S1327.3. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011 Guidelines of Malaria. Seoul, Korea: The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2011. p. 51.4. Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, et al. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993; 61:315–320.

Article5. Toma H, Kobayashi J, Vannachone B, Arakawa T, Sato Y, Nambanya S, et al. Plasmodium ovale infections detected by PCR assay in Lao PDR. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999; 30:620–622.6. Moon S, Kim BN, Kuak EY, Han TH. A case of Plasmodium ovale malaria imported from West Africa. Lab Med Online. 2012; 2:51–54.

Article7. Kang MS, Choi JW, Nahm CH, Pai SH. A case of cerebral malaria associated with renal failure due to Plasmodium falciparum. Korean J Clin Pathol. 2000; 20:459–462.8. Molineaux L. The epidemiology of human malaria as an explanation of its distribution, including some implications for control. In : Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor LA, editors. Malaria: principles and practices of malariology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;1988. p. 913–998.9. Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007; 20:579–592.10. Im KI, editor. Human parasitology. 1st ed. Seoul: Uihakmunhwasa;1992. p. 90–91.11. Eiam-Ong S. Malarial nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2003; 23:21–33.

Article12. Park TS, Kim JH, Kang CI, Lee BH, Jeon BR, Lee SM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of SD malaria antigen and antibody kits for differential diagnosis of vivax malaria in patients with fever of unknown origin. Korean J Lab Med. 2006; 26:241–245.

Article13. Kang Y, Yang J. A case of Plasmodium ovale malaria imported from West Africa. Korean J Parasitol. 2013; 51:213–218.

Article14. Cho D, Lim CS, Kim DL, Ryang DW. Diagnosis and treatment monitoring of Plasmodium vivax malaria using the OptiMAL test in South Korean soldiers. Korean J Clin Pathol. 2001; 21:235–239.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Diagnosis and Molecular Analysis on Imported Plasmodium ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri Malaria Cases from West and South Africa during 2013-2016

- Characteristics of Imported Malaria and Species of Plasmodium Involved in Shandong Province, China (2012-2014)

- A Case of Imported Plasmodium malariae Malaria

- A Case of Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax Malaria Imported from Indonesia

- A Case of Plasmodium vivax Infection Diagnosed after Treatment of Imported Falciparum Malaria