Korean J Obstet Gynecol.

2010 Mar;53(3):227-234. 10.5468/kjog.2010.53.3.227.

A prospective multicenter randomized study on prophylactic antibiotics use in cesarean section performed at tertiary center

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggyepaik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ymkcho@paik.ac.kr

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2273848

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/kjog.2010.53.3.227

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether the duration and timing of prophylactic antibiotics influence maternal postoperative infectious morbidity in cesarean section performed at tertiary center.

METHODS

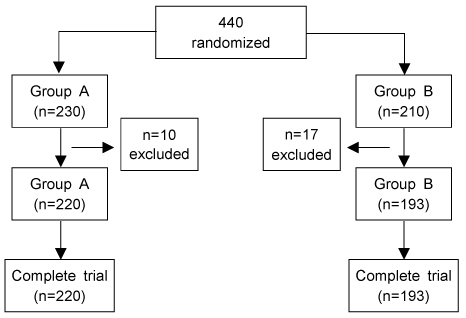

This study was a prospective, randomized trial. Pregnant women who underwent cesarean section between December 2008 and September 2009 at tertiary center were enrolled and divided into two groups: Group A, antibiotic prophylaxis was applied for 24 hours and Group B, antibiotic prophylaxis was applied for 48 hours. First generation of cephalosporin was administrated within 30 minutes prior skin incision or after cord clamping. The occurrence of postoperative infectious morbidity such as febrile morbidity, wound infection, endometritis, urinary track infection, pneumonia, sepsis and pelvic abscess and hospital stays were compared.

RESULTS

There were 413 pregnant women enrolled and then randomized into 220 for group A and 197 for group B. No demographic differences were observed between two groups. The infectious morbidity was 1.9% (8/413) and wound infection was the most common postoperative infections morbidity. No significant difference was found between the groups for infectious morbidity and hospital stays. Also timing of prophylactic antibiotics did not result in significant difference for infectious morbidity.

CONCLUSION

Short course of prophylactic antibiotics has been shown to be as efficacious as multidose of prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infectious morbidity in cesarean section and timing did not influence on infections morbidity. Further studies focusing on duration and timing of prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean section are needed.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Prophylactic antibiotics in intra-oral bone grafting procedures: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial

Jung-Woo Lee, Jin-Yong Lee, Soung-Min Kim, Myung-Jin Kim, Jong-Ho Lee

J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;38(2):90-95. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2012.38.2.90.Overview of Antibiotic Use in Korea

Baek-Nam Kim

Infect Chemother. 2012;44(4):250-262. doi: 10.3947/ic.2012.44.4.250.Comparing the Postoperative Complications, Hospitalization Days and Treatment Expenses Depending on the Administration of Postoperative Prophylactic Antibiotics to Hysterectomy

Mi Young Jung, Kyung-Yeon Park

Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017;23(1):42-51. doi: 10.4069/kjwhn.2017.23.1.42.

Reference

-

2. Gibbs RS. Clinical risk factors for puerperal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1980. 55:5 suppl. 178S–184S.

Article3. Yokoe DS, Christiansen CL, Johnson R, Sands KE, Livingston J, Shtatland ES, et al. Epidemiology of and surveillance for postpartum infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001. 7:837–841.

Article4. Henderson E, Love EJ. Incidence of hospital acquired infections associated with cesarean section. J Hosp Infect. 1995. 29:245–255.5. Kim JM, Park ES, Jeong JS, Kim KM, Kim JM, Oh YS, et al. Multicenter surveillance study for nosocomial infections in major hospitals in Korea. Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Committee of the Korean Society for Nosocomial Infection Control. Am J Infect Control. 2000. 28:454–458.7. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004. 32:470–485.8. Bratzler DW, Houck PM, et al. Surgical Infection Prevention Guidelines Writers Workgroup. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. American Association of Critical Care Nurses. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the national surgical infection prevention project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 38:1706–1715.

Article9. Hopkins L, Smaill F. Antibiotic prophylaxis regimens and drugs for cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. CD001136.

Article10. Sullivan SA, Smith T, Chang E, Huley T, Vandorsten JP, Soper D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 196:455.e1–455.e5.

Article11. Smaill F, Hofmeyr GJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002. CD000933.

Article12. Gibbs RS, St Clair PJ, Castillo MS, Castaneda YS. Bacteriologic effects of antibiotic prophylaxis in high risk cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1981. 57:277–282.13. Bagratte JS, Moodley J, Kleinschmidt I, Zawilski W. A randomized controlled trial of antibiotic prophylaxis in elective cesarean delivery. BJOG. 2001. 108:143–148.14. Mahomed K. A double-blind randomized controlled trial on the use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients undergoing elective cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1988. 95:689–692.15. Yip SK, Lau TR, Rogers MS. A study on prophylactic antibiotics in cesarean sections- is it worthwhile. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997. 76:547–549.16. Rizk DEE, Nsanze H, Mabrouk MH, Mustafa N, Thomas L, Kumar M. Systemic antibiotics prophylaxis in elective cesarean delivery. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1998. 61:245–251.17. Duff P, Smith PN, Keiser JF. Antibiotic prophylaxis in low-risk cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 1982. 27:133–138.18. Chelmow D, Ruehli MS, Huang E. Prophylactic use of antibiotics for nonlaboring patients undergoing cesarean delivery with intact membranes: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 184:656–661.

Article19. ACOG. Prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004. 84:300–307.20. Faro S, Martens MG, Hammill HA, Riddle G, Tortolero G. Antibiotic prophylaxis: Is there a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 162:900–907. discussion 907-9.

Article21. Gonik B. Single-versus three-dose cefotaxime prophylaxis for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 65:189–193.22. Roex AJ, Puyenbroek JI, van Loenen AC, Arts NF. Single versus three dose cefoxitin prophylaxis in cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987. 25:293–298.23. Saltzman DH, Eron LJ, Tuomala RE, Protomastro LJ, Sites JG. Single-dose antibiotic prophylxis in high-risk patients undergoing cesarean section. A comparative trial. J Reprod Med. 1986. 31:709–712.26. Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008. 111:51–56.

Article27. Burke JF. The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery. 1961. 50:161–168.28. ASHP Therapeutic guidelines on antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999. 56:1839–1888.29. Wong-Beringer A, Corelli RL, Schrock TR, Guglielmo BJ. Influence of timing of antibiotic administration on tissue concentrations during surgery. Am J Surg. 1995. 169:379–381.

Article30. Classen DC, Evans RS, Pestotnik SI, Horn SD, Menlove RL, Burke JP. The Timing of prophylactic administration of antibiotics and the risk of surgical wound infection. N Engl J Med. 1992. 326:281–286.31. Dietz V, Wijers B, Pijnenborg JM. Timing of prophylactic antibiotic administration in the uninfected laboring gravid: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 194:1741–1742.32. Wax JR, Hersey K, Philput C, Wright MS, Nichols KV, Eggleston MK, et al. Single dose cefazolin prophylaxis for postcesarean infections: before and after cord clamping. J Matern Fetal Med. 1997. 6:61–65.33. Yildirim G, Gungorduk K, Guven HZ, Aslan H, Celikkol O, Sudolmus S, et al. When should we perform prophylactic antibiotics in elective cesarean cases? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009. 280:13–18.

Article34. Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghylmiyah L, Byers BD, Longo M, Wen T, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008. 199:301.e1–301.e6.

Article35. Tita AT, Rouse DJ, Blackwell S, Saade GR, Spong CY, Andrews WW. Emerging concepts in antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 113:675–682.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Prophylactic antibiotics in elective cesarean section

- Comparative Study of Single-dose Prophylactic Antibiotics after Cord Clamping Vs. Multi-dose Postoperative Antibiotics in Operative Complications after Elective Cesarean Section

- Prophylactic intravenous ephedrine infusion during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section

- Comparative Study of Intrauterine Irrigation and Intravenous Injection with Cephradine at Cesarean Section

- Could Emesis from Epidural Anesthesia for a Cesarean Section be Controlled by Prophylactic Low-Dose Granisetron?