J Bacteriol Virol.

2011 Dec;41(4):213-223. 10.4167/jbv.2011.41.4.213.

Herpesviral Interaction with Autophagy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. chengyu.liang@usc.edu

- KMID: 2168649

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2011.41.4.213

Abstract

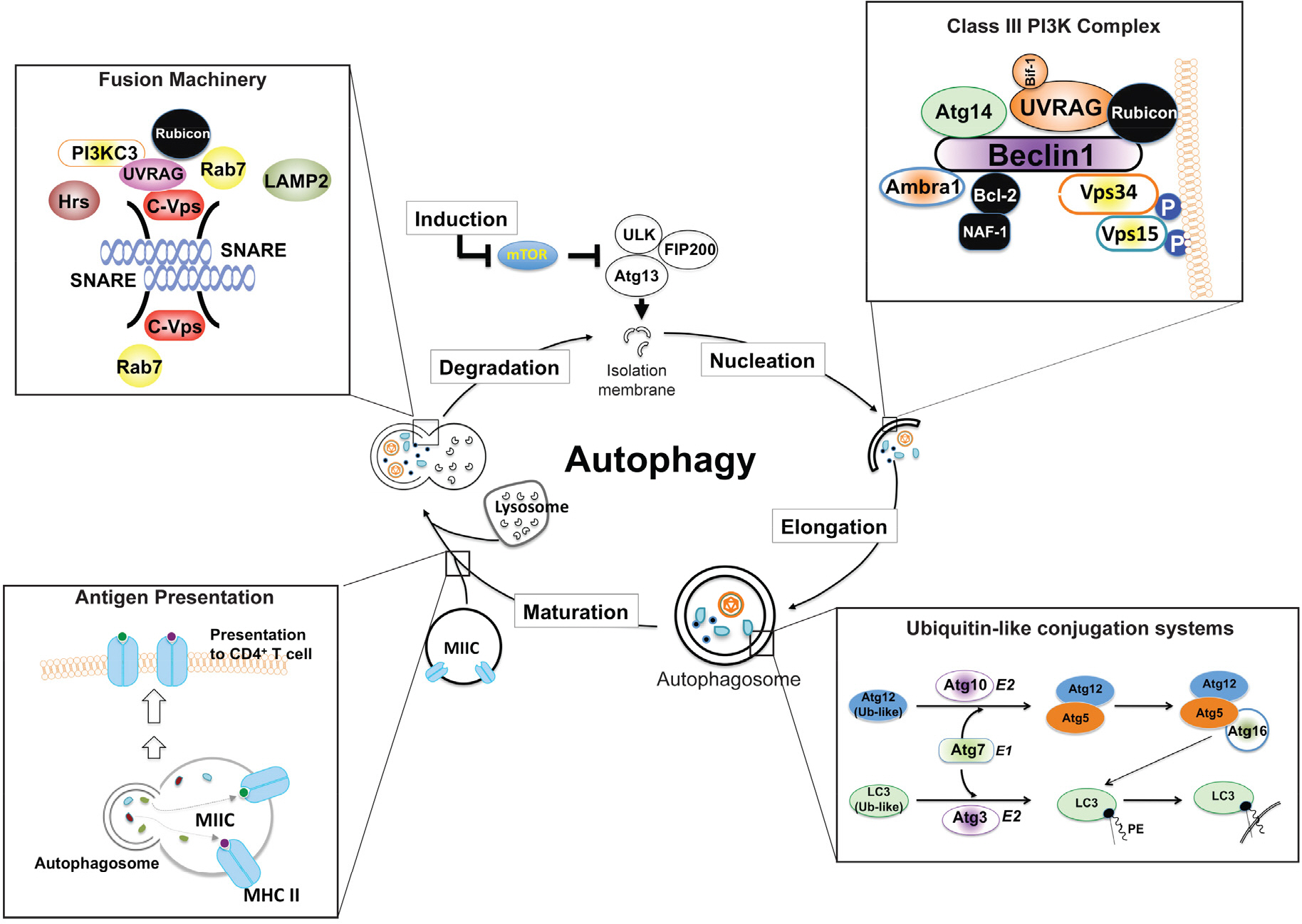

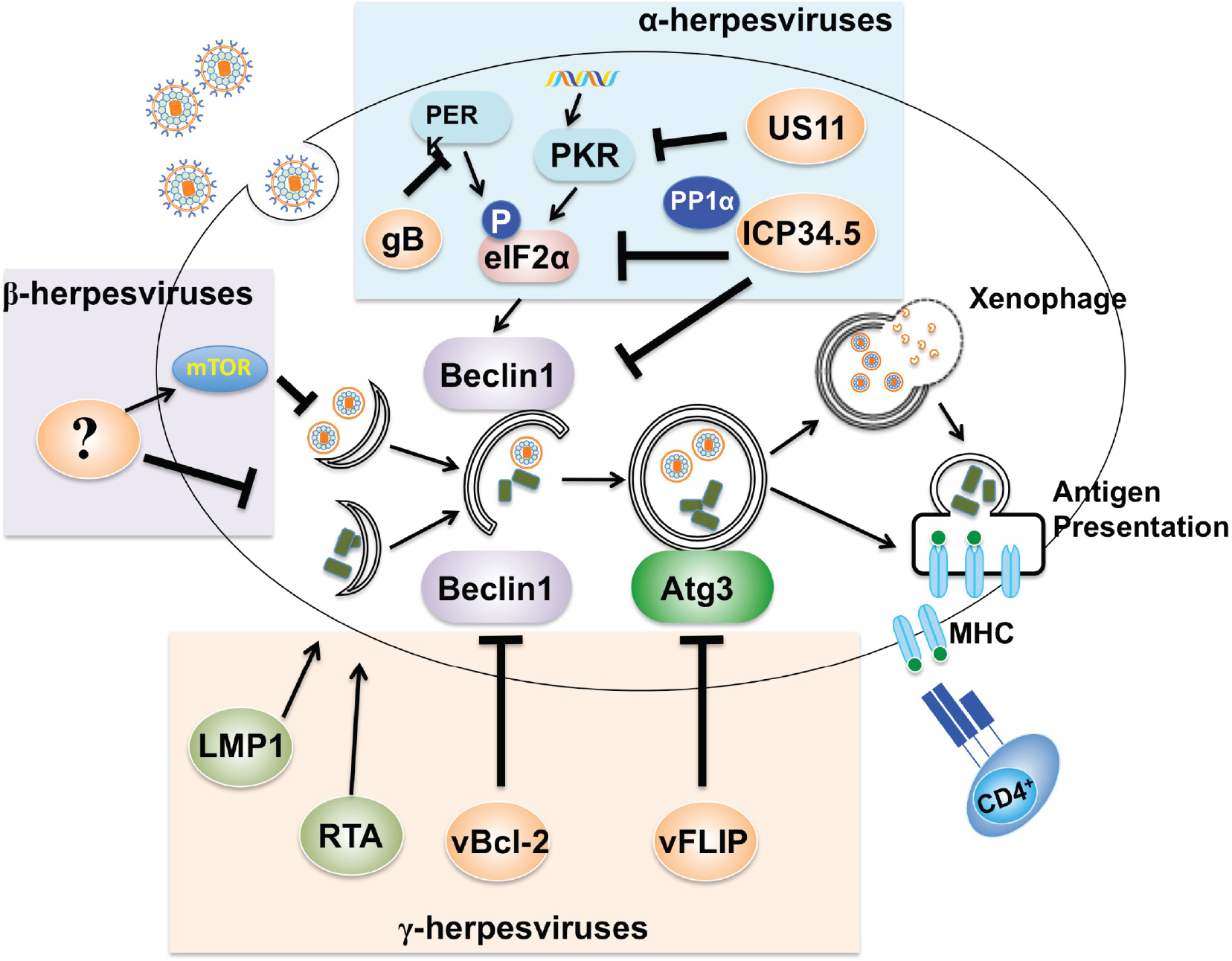

- Autophagy constitutes a major catabolic hub for the quality control of intracellular entities of eukaryotic cells, and is emerging as an essential part of the host antiviral defense mechanism. However, in turn, viruses have evolved elegant strategies to co-opt various stages of the cellular autophagy pathway to establish virulence in vivo. This is particularly the case in the ubiquitous and persistent herpesvirus infection. In this review, I will focus on recent findings regarding the crosstalk between the herpes virus family and the autophagy pathway, with a look at the molecular mechanisms they use to disturb cells' autophagy regulation and eventually result in persistence and pathogenesis.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Current Understanding of HMGB1-mediated Autophagy

Man Sup Kwak, Jeon-Soo Shin

J Bacteriol Virol. 2013;43(2):148-154. doi: 10.4167/jbv.2013.43.2.148.

Reference

-

1). Kudchodkar SB, Levine B. Viruses and autophagy. Rev Med Virol. 2009; 19:359–78.

Article2). Virgin HW, Levine B. Autophagy genes in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2009; 10:461–70.

Article3). Kim HJ, Lee S, Jung JU. When autophagy meets viruses: a double-edged sword with functions in defense and offense. Semin Immunopathol. 2010; 32:323–41.

Article4). Campoy E, Colombo MI. Autophagy subversion by bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009; 335:227–50.

Article5). Deretic V. Autophagy in infection. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010; 22:252–62.

Article6). Shoji-Kawata S, Levine B. Autophagy, antiviral immunity, and viral countermeasures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009; 1793:1478–84.

Article7). Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007; 8:931–7.

Article8). Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010; 22:124–31.

Article9). Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008; 132:27–42.

Article10). Neufeld TP. TOR-dependent control of autophagy: biting the hand that feeds. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010; 22:157–68.

Article11). Liang C, Jung JU. Autophagy genes as tumor suppressors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010; 22:226–33.

Article12). Talloczy Z, Jiang W, Virgin HW 4th, Leib DA, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, et al. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2alpha kinase signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99:190–5.13). Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004; 6:463–77.14). Hayashi-Nishino M, Fujita N, Noda T, Yamaguchi A, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009; 11:1433–7.

Article15). Yen WL, Shintani T, Nair U, Cao Y, Richardson BC, Li Z, et al. The conserved oligomeric Golgi complex is involved in double-membrane vesicle formation during autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010; 188:101–14.

Article16). English L, Chemali M, Duron J, Rondeau C, Laplante A, Gingras D, et al. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2009; 10:480–7.

Article17). Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010; 141:656–67.

Article18). Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010; 12:747–57.

Article19). Liang C. Negative regulation of autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2010; 17:1807–15.

Article20). E X, Hwang S, Oh S, Lee JS, Jeong JH, Gwack Y, et al. Viral Bcl-2-mediated evasion of autophagy aids chronic infection of gammaherpesvirus 68. PLoS Pathog. 2009; 5:e1000609.21). Orvedahl A, Levine B. Autophagy and viral neurovirulence. Cell Microbiol. 2008; 10:1747–56.

Article22). Orvedahl A, Alexander D, Tallóczy Z, Sun Q, Wei Y, Zhang W, et al. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2007; 1:23–35.

Article23). Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, et al. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature. 2009; 461:654–8.

Article24). Eskelinen EL. Maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Mammalian cells. Autophagy. 2005; 1:1–10.

Article25). Nara A, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. SKD1 AAA ATPase-dependent endosomal transport is involved in autolysosome formation. Cell Struct Funct. 2002; 27:29–37.

Article26). Tamai K, Tanaka N, Nara A, Yamamoto A, Nakagawa I, Yoshimori T, et al. Role of Hrs in maturation of autophagosomes in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007; 360:721–7.

Article27). Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, et al. Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10:776–87.

Article28). Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT, et al. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2009; 11:468–76.

Article29). Li Y, Wang LX, Yang G, Hao F, Urba WJ, Hu HM. Efficient cross-presentation depends on autophagy in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2008; 68:6889–95.

Article30). Taylor GS, Mautner J, Munz C. Autophagy in herpesvirus immune control and immune escape. Herpesviridae. 2011; 2:2.

Article31). Chemali M, Radtke K, Desjardins M, English L. Alternative pathways for MHC class I presentation: a new function for autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011; 68:1533–41.

Article32). Liang C, Lee JS, Jung JU. Immune evasion in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus associated oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008; 18:423–36.

Article33). Damania B. Oncogenic gamma-herpesviruses: comparison of viral proteins involved in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004; 2:656–68.34). Knipe DM, Cliffe A. Chromatin control of herpes simplex virus lytic and latent infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008; 6:211–21.

Article35). Thorley-Lawson DA, Allday MJ. The curious case of the tumour virus: 50 years of Burkitt's lymphoma. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008; 6:913–24.

Article36). Levine B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell. 2005; 120:159–62.37). Tallóczy Z, Virgin HW 4th, Levine B. PKR-dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy. 2006; 2:24–9.38). He B, Gross M, Roizman B. The gamma(1)34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1alpha to dephosphorylate the alpha subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94:843–8.39). Chou J, Kern ER, Whitley RJ, Roizman B. Mapping of herpes simplex virus-1 neurovirulence to gamma 134.5, a gene nonessential for growth in culture. Science. 1990; 250:1262–6.40). Orvedahl A, Levine B. Eating the enemy within: autophagy in infectious diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2009; 16:57–69.

Article41). Alexander DE, Ward SL, Mizushima N, Levine B, Leib DA. Analysis of the role of autophagy in replication of herpes simplex virus in cell culture. J Virol. 2007; 81:12128–34.

Article42). Alexander DE, Leib DA. Xenophagy in herpes simplex virus replication and pathogenesis. Autophagy. 2008; 4:101–3.

Article43). Dengjel J, Schoor O, Fischer R, Reich M, Kraus M, Müller M, et al. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102:7922–7.

Article44). Wu H, Kapoor P, Frappier L. Separation of the DNA replication, segregation, and transcriptional activation functions of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1. J Virol. 2002; 76:2480–90.

Article45). Paludan C, Schmid D, Landthaler M, Vockerodt M, Kube D, Tuschl T, et al. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science. 2005; 307:593–6.

Article46). Leung CS, Haigh TA, Mackay LK, Rickinson AB, Taylor GS. Nuclear location of an endogenously expressed antigen, EBNA1, restricts access to macro-autophagy and the range of CD4 epitope display. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:2165–70.

Article47). Hansen TH, Bouvier M. MHC class I antigen presentation: learning from viral evasion strategies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009; 9:503–13.

Article48). Leib DA, Alexander DE, Cox D, Yin J, Ferguson TA. Interaction of ICP34.5 with Beclin 1 modulates herpes simplex virus type 1 pathogenesis through control of CD4+ T-cell responses. J Virol. 2009; 83:12164–71.49). Broberg EK, Peltoniemi J, Nygårdas M, Vahlberg T, Röyttä M, Hukkanen V. Spread and replication of and immune response to gamma134.5-negative herpes simplex virus type 1 vectors in BALB/c mice. J Virol. 2004; 78:13139–52.50). English L, Chemali M, Desjardins M. Nuclear membrane-derived autophagy, a novel process that participates in the presentation of endogenous viral antigens during HSV-1 infection. Autophagy. 2009; 5:1026–9.

Article51). Lin LT, Dawson PW, Richardson CD. Viral interactions with macroautophagy: a double-edged sword. Virology. 2010; 402:1–10.

Article52). Harrow S, Papanastassiou V, Harland J, Mabbs R, Petty R, Fraser M, et al. HSV1716 injection into the brain adjacent to tumour following surgical resection of high-grade glioma: safety data and long-term survival. Gene Ther. 2004; 11:1648–58.

Article53). Chou J, Chen JJ, Gross M, Roizman B. Association of a M(r) 90,000 phosphoprotein with protein kinase PKR in cells exhibiting enhanced phosphorylation of translation initiation factor eIF-2 alpha and premature shutoff of protein synthesis after infection with gamma 134.5- mutants of herpes simplex virus 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92:10516–20.

Article54). Markovitz NS, Baunoch D, Roizman B. The range and distribution of murine central nervous system cells infected with the gamma(1)34.5-mutant of herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 1997; 71:5560–9.55). He B, Chou J, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B, Roizman B. The carboxyl terminus of the murine MyD116 gene substitutes for the corresponding domain of the gamma(1)34.5 gene of herpes simplex virus to preclude the premature shutoff of total protein synthesis in infected human cells. J Virol. 1996; 70:84–90.

Article56). Orvedahl A, Levine B. Viral evasion of autophagy. Autophagy. 2008; 4:280–5.

Article57). Mulvey M, Poppers J, Sternberg D, Mohr I. Regulation of eIF2alpha phosphorylation by different functions that act during discrete phases in the herpes simplex virus type 1 life cycle. J Virol. 2003; 77:10917–28.58). Peters GA, Khoo D, Mohr I, Sen GC. Inhibition of PACT-mediated activation of PKR by the herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein. J Virol. 2002; 76:11054–64.

Article59). Mulvey M, Arias C, Mohr I. Maintenance of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected cells through the association of a viral glycoprotein with PERK, a cellular ER stress sensor. J Virol. 2007; 81:3377–90.

Article60). Griffiths P. Cytomegalovirus infection of the central nervous system. Herpes. 2004; 2:95A–104A.61). Chaumorcel M, Souquère S, Pierron G, Codogno P, Esclatine A. Human cytomegalovirus controls a new autophagy-dependent cellular antiviral defense mechanism. Autophagy. 2008; 4:46–53.

Article62). Oh S, E X, Hwang S, Liang C. Autophagy evasion in herpesviral latency. Autophagy. 2010; 6:151–2.

Article63). Cheng EH, Nicholas J, Bellows DS, Hayward GS, Guo HG, Reitz MS, et al. A Bcl-2 homolog encoded by Kaposi sarcoma-associated virus, human herpesvirus 8, inhibits apoptosis but does not heterodimerize with Bax or Bak. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94:690–4.

Article64). Ojala PM, Tiainen M, Salven P, Veikkola T, Castaños-Vélez E, Sarid R, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded v-cyclin triggers apoptosis in cells with high levels of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Cancer Res. 1999; 59:4984–9.65). Wang GH, Garvey TL, Cohen JI. The murine gammaherpesvirus-68 M11 protein inhibits Fas- and TNF-induced apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 1999; 80:2737–40.66). Loh J, Huang Q, Petros AM, Nettesheim D, van Dyk LF, Labrada L, et al. A surface groove essential for viral Bcl-2 function during chronic infection in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2005; 1:e10.67). Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005; 122:927–39.

Article68). Maiuri MC, Criollo A, Tasdemir E, Vicencio JM, Tajeddine N, Hickman JA, et al. BH3-only proteins and BH3 mimetics induce autophagy by competitively disrupting the interaction between Beclin 1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-X(L). Autophagy. 2007; 3:374–6.

Article69). Sinha S, Colbert CL, Becker N, Wei Y, Levine B. Molecular basis of the regulation of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by the gamma-herpesvirus 68 Bcl-2 homolog M11. Autophagy. 2008; 4:989–97.70). Ku B, Woo JS, Liang C, Lee KH, Jung JU, Oh BH. An insight into the mechanistic role of Beclin 1 and its inhibition by prosurvival Bcl-2 family proteins. Autophagy. 2008; 4:519–20.

Article71). Oh S, E X, Hwang S, Liang C. Autophagy evasion in herpesviral latency. Autophagy. 2010; 6:151–2.

Article72). Lee JS, Li Q, Lee JY, Lee SH, Jeong JH, Lee HR, et al. FLIP-mediated autophagy regulation in cell death control. Nat Cell Biol. 2009; 11:1355–62.

Article73). Chaudhary PM, Jasmin A, Eby MT, Hood L. Modulation of the NF-kappa B pathway by virally encoded death effector domains-containing proteins. Oncogene. 1999; 18:5738–46.74). Guasparri I, Keller SA, Cesarman E. KSHV vFLIP is essential for the survival of infected lymphoma cells. J Exp Med. 2004; 199:993–1003.

Article75). Sun Q, Zachariah S, Chaudhary PM. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE-inhibitory protein induces cellular transformation via NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:52437–45.76). Qing G, Yan P, Qu Z, Liu H, Xiao G. Hsp90 regulates processing of NF-kappa B2 p100 involving protection of NF-kappa B-inducing kinase (NIK) from autophagy-mediated degradation. Cell Res. 2007; 17:520–30.77). Lee DY, Sugden B. The latent membrane protein 1 oncogene modifies B-cell physiology by regulating autophagy. Oncogene. 2008; 27:2833–42.

Article78). Wen HJ, Yang Z, Zhou Y, Wood C. Enhancement of autophagy during lytic replication by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication and transcription activator. J Virol. 2010; 84:7448–58.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Interplay Between Primary Cilia and Autophagy and Its Controversial Roles in Cancer

- The role of autophagy in cell proliferation and differentiation during tooth development

- Neuronal Autophagy: Characteristic Features and Roles in Neuronal Pathophysiology

- Autophagy in the placenta

- ZFP36L1 and AUF1 Induction Contribute to the Suppression of Inflammatory Mediators Expression by Globular Adiponectin via Autophagy Induction in Macrophages