Allergy Asthma Immunol Res.

2016 Jul;8(4):353-361. 10.4168/aair.2016.8.4.353.

Characteristics of Anaphylaxis in 907 Chinese Patients Referred to a Tertiary Allergy Center: A Retrospective Study of 1,952 Episodes

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Allergy, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China. doctoryinjia@163.com

- KMID: 2165919

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2016.8.4.353

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Comprehensive evaluation of anaphylaxis in China is currently lacking. In this study, we characterized the clinical profiles, anaphylactic triggers, and emergency treatment in pediatric and adult patients.

METHODS

Outpatients diagnosed with "anaphylaxis" or "severe allergic reactions" in the Department of Allergy, Peking Union Medical College Hospital from January 1, 2000 to June 30, 2014 were analyzed retrospectively.

RESULTS

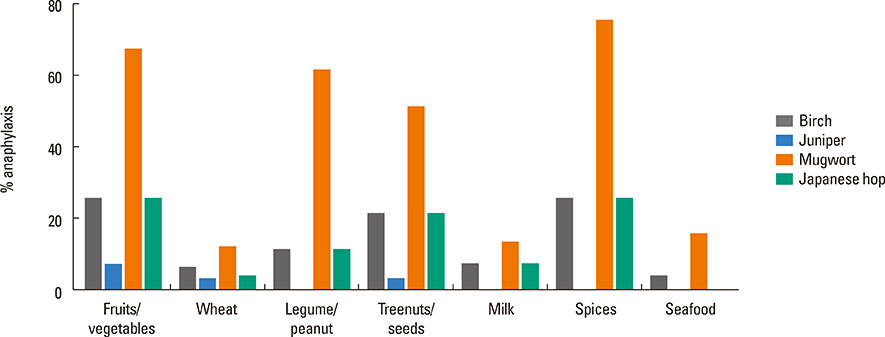

A total of 1,952 episodes of anaphylaxis in 907 patients were analyzed (78% were adults and 22% were children). Foods are the most common cause (77%), followed by idiopathic etiologies (15%), medications (7%) and insects (0.6%). In food-induced anaphylaxis, 62% (13/21) of anaphylaxis in infants and young children (0-3 years of age) were triggered by milk, 59% (36/61) of anaphylaxis in children (4-9 years of age) were triggered by fruits/vegetables, while wheat was the cause of anaphylaxis in 20% (56/282) of teenagers (10-17 years of age) and 42% (429/1,016) in adults (18-50 years of age). Mugwort pollen sensitization was common in patients with anaphylaxis induced by spices, fruits/vegetables, legume/peanuts, and tree nuts/seeds, with the prevalence rates of 75%, 67%, 61%, and 51%, respectively. Thirty-six percent of drug-induced anaphylaxis was attributed to traditional Chinese Medicine. For patients receiving emergency care, only 25% of patients received epinephrine.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study showed that anaphylaxis appeared to occur more often in adults than in infants and children, which were in contrast to those found in other countries. In particular, wheat allergens played a prominent role in triggering food-induced anaphylaxis, followed by fruits/vegetables. Traditional Chinese medicine was a cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis. Furthermore, exercise was the most common factor aggravating anaphylaxis. Education regarding the more aggressive use of epinephrine in the emergency setting is clearly needed.

MeSH Terms

-

Adolescent

Adult

Allergens

Anaphylaxis*

Artemisia

Asian Continental Ancestry Group*

Child

China

Education

Emergencies

Emergency Medical Services

Emergency Treatment

Epinephrine

Humans

Hypersensitivity*

Infant

Insects

Medicine, Chinese Traditional

Milk

Outpatients

Pollen

Prevalence

Retrospective Studies*

Spices

Trees

Triticum

Wheat Hypersensitivity

Allergens

Epinephrine

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

The past, present, and future of research on anaphylaxis in Korean children

Sooyoung Lee

Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2018;6(Suppl 1):S21-S30. doi: 10.4168/aard.2018.6.S1.S21.Pilot Project of Special Emergency Medical Service Team for Anaphylaxis in Gangwon-do, Korea: Results from an Online Questionnaire Survey

Hyeonseung Lee, Jae-Woo Kwon, Yong Whi Jeong, Changhoon Lee, Jeongmin Lee

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(42):e258. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e258.Are Registration of Disease Codes for Adult Anaphylaxis Accurate in the Emergency Department?

Byungho Choi, Sun Hyu Kim, Hyeji Lee

Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(2):137-143. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.2.137.

Reference

-

1. Simons FE. Anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:Suppl 2. S161–S181.2. Sheikh A, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Fenty J. Trends in national incidence, lifetime prevalence and adrenaline prescribing for anaphylaxis in England. J R Soc Med. 2008; 101:139–143.3. Huang F, Chawla K, Järvinen KM, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Anaphylaxis in a New York City pediatric emergency department: triggers, treatments, and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 129:162–168.e1.4. Ben-Shoshan M, La Vieille S, Eisman H, Alizadehfar R, Mill C, Perkins E, et al. Anaphylaxis treated in a Canadian pediatric hospital: Incidence, clinical characteristics, triggers, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 132:739–741.e3.5. Banerji A, Rudders SA, Corel B, Garth AM, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Repeat epinephrine treatments for food-related allergic reactions that present to the emergency department. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010; 31:308–316.6. Solé D, Ivancevich JC, Borges MS, Coelho MA, Rosário NA, Ardusso L, et al. Latin American Anaphylaxis Working Group. Anaphylaxis in Latin American children and adolescents: the Online Latin American Survey on Anaphylaxis (OLASA). Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2012; 40:331–335.7. Shek LP, Lee BW. Food allergy in Asia. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 6:197–201.8. Yang MS, Lee SH, Kim TW, Kwon JW, Lee SM, Kim SH, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of anaphylaxis in Korea. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008; 100:31–36.9. Beyer K, Eckermann O, Hompes S, Grabenhenrich L, Worm M. Anaphylaxis in an emergency setting - elicitors, therapy and incidence of severe allergic reactions. Allergy. 2012; 67:1451–1456.10. Liew WK, Williamson E, Tang ML. Anaphylaxis fatalities and admissions in Australia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:434–442.11. Smit DV, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Anaphylaxis presentations to an emergency department in Hong Kong: incidence and predictors of biphasic reactions. J Emerg Med. 2005; 28:381–388.12. Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF Jr, Bock SA, Branum A, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report--second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 47:373–380.13. Adkinson NF, Bochner BS, Burks AW, Busse WW, Holgate ST, Lemanske RF, et al. Middleton's allergy: principles and practice. eighth edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2014. p. 1119–1132.14. Lauritano EC, Novi A, Santoro MC, Casagranda I. Incidence, clinical features and management of acute allergic reactions: the experience of a single, Italian Emergency Department. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013; 17:Suppl 1. 39–44.15. Hsin YC, Hsin YC, Huang JL, Yeh KW. Clinical features of adult and pediatric anaphylaxis in Taiwan. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011; 29:307–312.16. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, Jick H, Miller RL, Sheikh A, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 97:596–602.17. Panesar SS, Javad S, de Silva D, Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Muraro A, et al. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013; 68:1353–1361.18. Hompes S, Köhli A, Nemat K, Scherer K, Lange L, Rueff F, et al. Provoking allergens and treatment of anaphylaxis in children and adolescents--data from the anaphylaxis registry of German-speaking countries. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011; 22:568–574.19. Mehl A, Wahn U, Niggemann B. Anaphylactic reactions in children--a questionnaire-based survey in Germany. Allergy. 2005; 60:1440–1445.20. Rolla G, Mietta S, Raie A, Bussolino C, Nebiolo F, Galimberti M, et al. Incidence of food anaphylaxis in Piemonte region (Italy): data from registry of Center for Severe Allergic Reactions. Intern Emerg Med. 2013; 8:615–620.21. Worm M, Edenharter G, Ruëff F, Scherer K, Pföhler C, Mahler V, et al. Symptom profile and risk factors of anaphylaxis in Central Europe. Allergy. 2012; 67:691–698.22. Cai PP, Yin J. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms and wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis in Chinese population. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013; 126:1159–1165.23. Palosuo K, Varjonen E, Kekki OM, Klemola T, Kalkkinen N, Alenius H, et al. Wheat omega-5 gliadin is a major allergen in children with immediate allergy to ingested wheat. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 108:634–638.24. Yin J, Wen LP. Wheat-dependent Exercise-induced Anaphylaxis Clinical and Laboratory Findings in 15 cases. Chin J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 4:8.25. Rudders SA, Banerji A, Vassallo MF, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in pediatric emergency department visits for food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:385–388.26. Park M, Kim D, Ahn K, Kim J, Han Y. Prevalence of immediate-type food allergy in early childhood in seoul. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014; 6:131–136.27. Goh DL, Lau YN, Chew FT, Shek LP, Lee BW. Pattern of food-induced anaphylaxis in children of an Asian community. Allergy. 1999; 54:84–86.28. Tai YS, JT Z, Jin GR. Investigation of aeroborne allergenic pollens in different regions of China. Beijing: Peking Publishing House;1991.29. Egger M, Mutschlechner S, Wopfner N, Gadermaier G, Briza P, Ferreira F. Pollen-food syndromes associated with weed pollinosis: an update from the molecular point of view. Allergy. 2006; 61:461–476.30. Ma S, Yin J, Jiang N. Component-resolved diagnosis of peach allergy and its relationship with prevalent allergenic pollens in China. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 132:764–767.31. Cao HS, He PB, Yang LZ. Analysis of 288 anaphylaxis cases induced by herb injections. Chin J Pharmacoepidemio. 2006; 15:26–27.32. Ye YM, Kim MK, Kang HR, Kim TB, Sohn SW, Koh YI, et al. Predictors of the severity and serious outcomes of anaphylaxis in Korean adults: a multicenter retrospective case study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2015; 7:22–29.33. Mullins RJ. Anaphylaxis: risk factors for recurrence. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003; 33:1033–1040.34. Morita E, Kunie K, Matsuo H. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. J Dermatol Sci. 2007; 47:109–117.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Idiopathic Anaphylaxis Followed by Acute Liver Injury

- Anaphylaxis diagnosis and management in the Emergency Department of a tertiary hospital in the Philippines

- Shellfish/crustacean oral allergy syndrome among national service pre-enlistees in Singapore

- Analysis of clinical characteristics of food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis at a single tertiary hospital

- A case study of apple seed and grape allergy with sensitisation to nonspecific lipid transfer protein