Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2025 May;29(3):307-319. 10.4196/kjpp.24.200.

Geraniin attenuates isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular apoptosis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong 226001, Jiangsu, China

- 2Department of Cardiology, Suzhou Kowloon Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Suzhou 215027, Jiangsu, China

- 3Department of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Nantong University, Nantong 226001, Jiangsu, China

- 4Department of Cardiology, Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan, China

- KMID: 2567189

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.24.200

Abstract

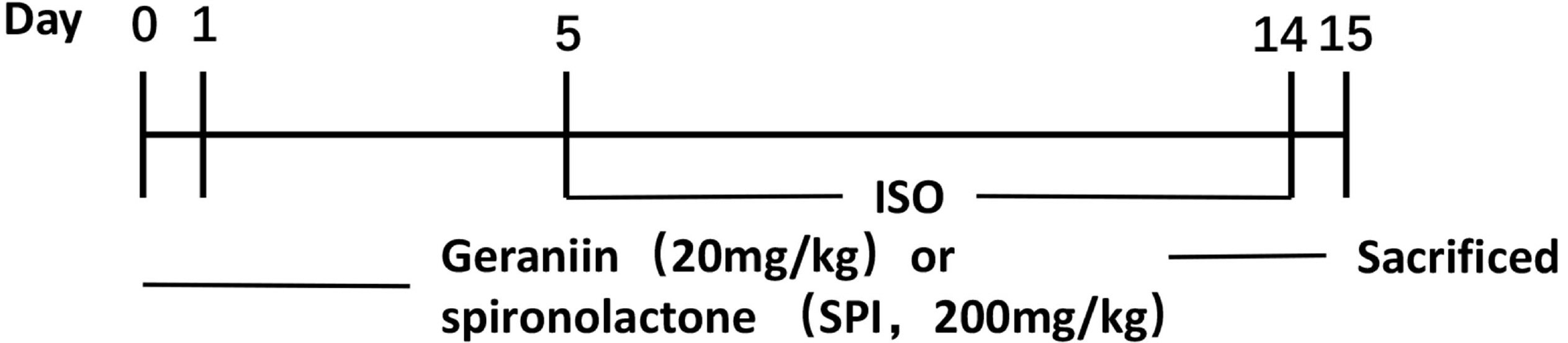

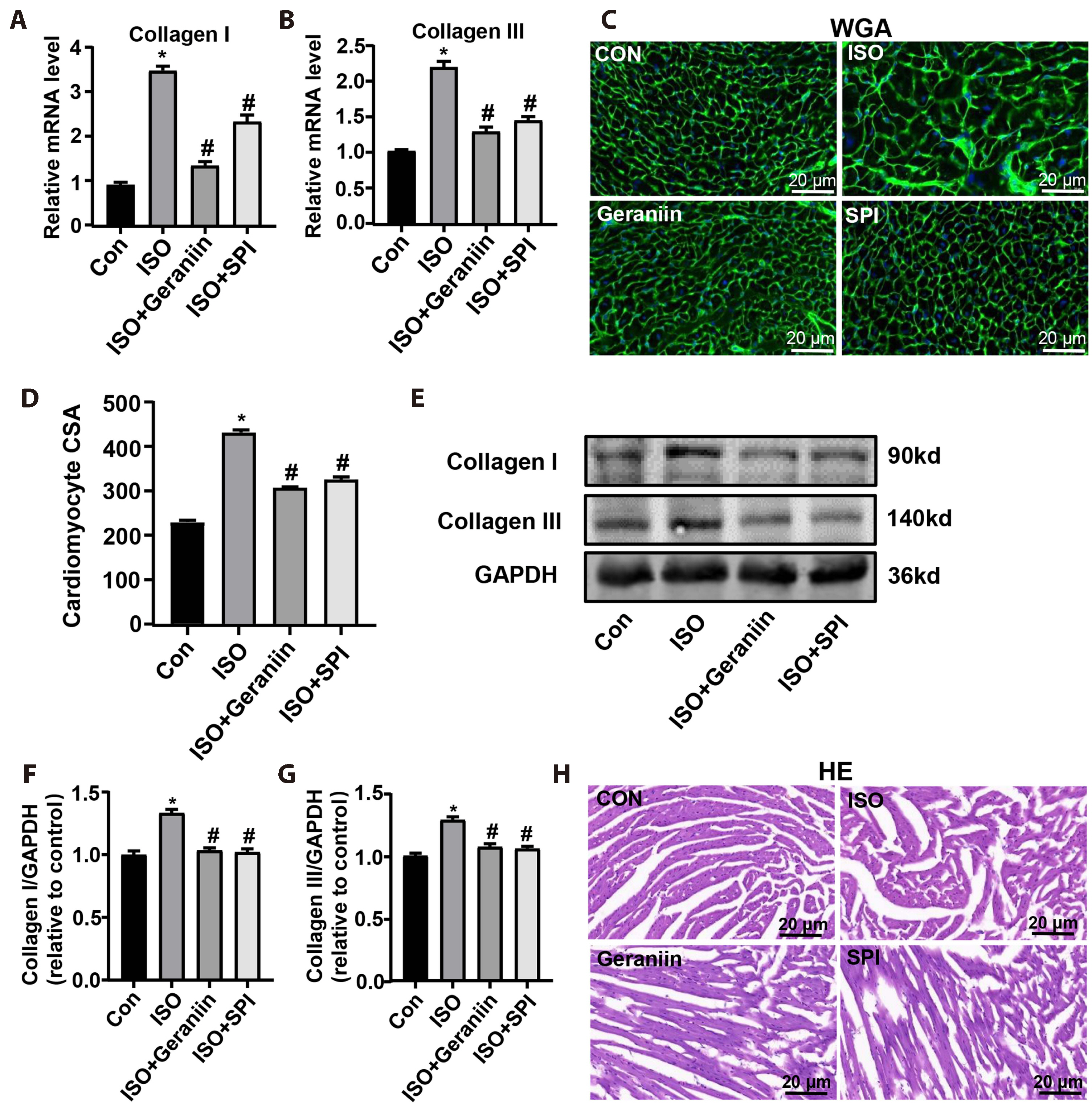

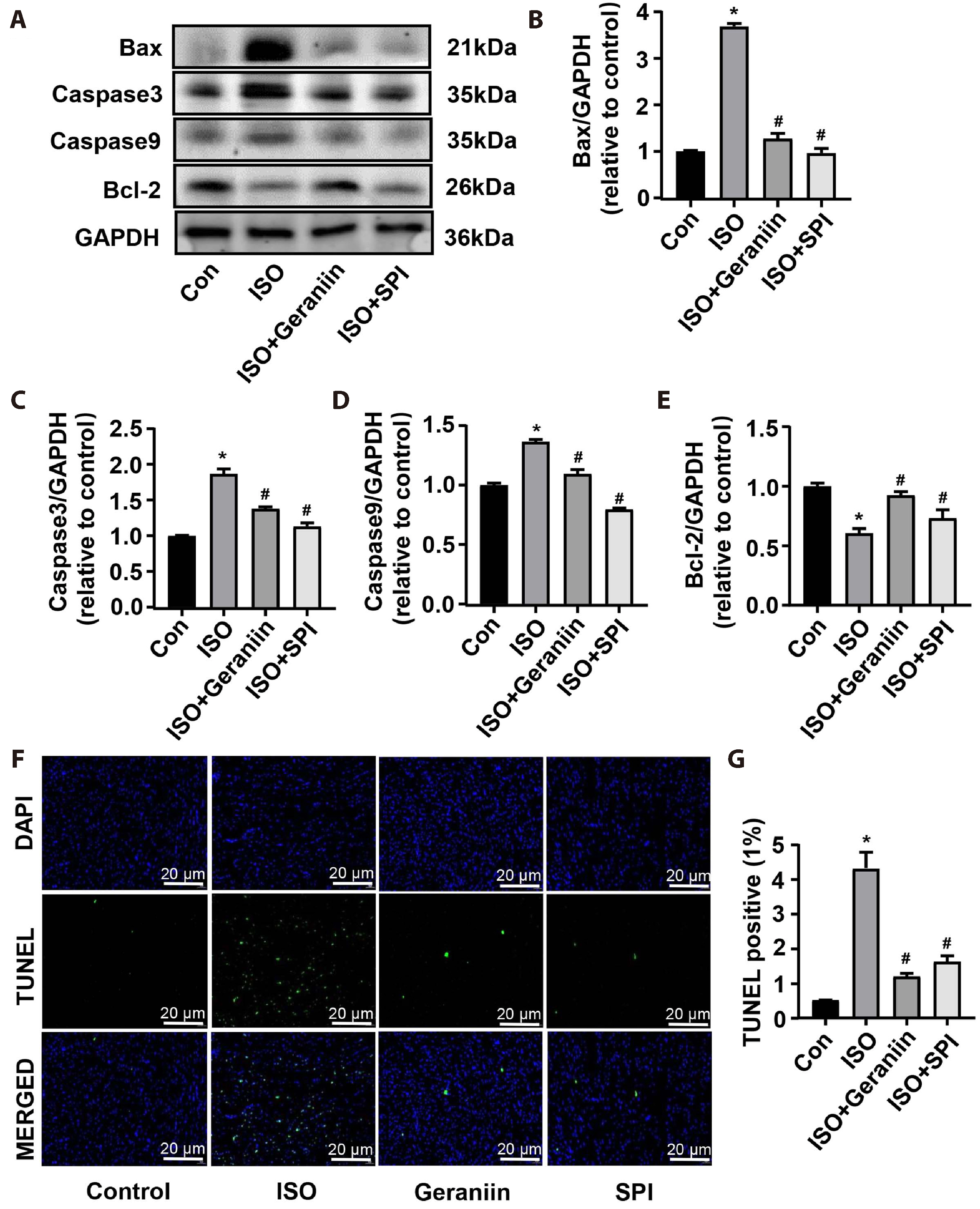

- Geraniin, a polyphenol derived from the fruit peel of Nephelium lappaceum L., has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in the cardiovascular system. The present study explored whether geraniin could protect against an isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy model. Mice in the ISO group received an intraperitoneal injection of ISO (5 mg/kg) once daily for 9 days, and the administration group were injected with ISO after 5 days of treatment with geraniin or spironolactone. Potential therapeutic effects and related mechanisms analysed by anatomical coefficients, histopathology, blood biochemical indices, reverse transcription-PCR and immunoblotting. Geraniin decreased the cardiac pathologic remodeling and myocardial fibrosis induced by ISO, as evidenced by the modifications to anatomical coefficients, as well as the reduction in collagen I/III á1mRNA and protein expression and cross-sectional area in hypertrophic cardiac tissue. In addition, geraniin treatment reduced ISO-induced increase in the mRNA and protein expression levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, whereas ISO-induced IL-10 showed the opposite behaviour in hypertrophic cardiac tissue. Further analysis showed that geraniin partially reversed the ISO-induced increase in malondialdehyde and nitric oxide, and the ISO-induced decrease in glutathione, superoxide dismutase and glutathione. Furthermore, it suppressed the ISO-induced cellular apoptosis of hypertrophic cardiac tissue, as evidenced by the decrease in Bcell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2)-associated X/caspase-3/caspase-9 expression, increase in Bcl-2 expression, and decrease in TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling-positive cells. These findings suggest that geraniin can attenuate ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular apoptosis.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Maillet M, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. 2013; Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: fundamental concepts and new players. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:38–48. DOI: 10.1038/nrm3495. PMID: 23258295. PMCID: PMC4416212.

Article2. van Berlo JH, Maillet M, Molkentin JD. 2013; Signaling effectors underlying pathologic growth and remodeling of the heart. J Clin Invest. 123:37–45. DOI: 10.1172/JCI62839. PMID: 23281408. PMCID: PMC3533272.

Article3. Tarone G, Balligand JL, Bauersachs J, Clerk A, De Windt L, Heymans S, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Hirsch E, Iaccarino G, Knöll R, Leite-Moreira AF, Lourenço AP, Mayr M, Thum T, Tocchetti CG. 2014; Targeting myocardial remodelling to develop novel therapies for heart failure: a position paper from the Working Group on Myocardial Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 16:494–508. DOI: 10.1002/ejhf.62. PMID: 24639064.

Article4. Nakamura M, Sadoshima J. 2018; Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 15:387–407. DOI: 10.1038/s41569-018-0007-y. PMID: 29674714.

Article5. Khalilimeybodi A, Daneshmehr A, Sharif-Kashani B. 2018; Investigating β-adrenergic-induced cardiac hypertrophy through computational approach: classical and non-classical pathways. J Physiol Sci. 68:503–520. DOI: 10.1007/s12576-017-0557-5. PMID: 28674776. PMCID: PMC10717155.

Article6. Shang L, Pin L, Zhu S, Zhong X, Zhang Y, Shun M, Liu Y, Hou M. 2019; Plantamajoside attenuates isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy associated with the HDAC2 and AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 307:21–28. DOI: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.024. PMID: 31009642.

Article7. Huang D, Yin L, Liu X, Lv B, Xie Z, Wang X, Yu B, Zhang Y. 2018; Geraniin protects bone marrowderived mesenchymal stem cells against hydrogen peroxideinduced cellular oxidative stress in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 41:739–748. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3276.

Article8. Yang Y, Zhang L, Fan X, Qin C, Liu J. 2012; Antiviral effect of geraniin on human enterovirus 71 in vitro and in vivo. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 22:2209–2211. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.102. PMID: 22342145.

Article9. Wang D, Dong X, Wang B, Liu Y, Li S. 2019; Geraniin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment in mice by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 activation. J Agric Food Chem. 67:10079–10088. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b03977. PMID: 31461286.

Article10. Elendran S, Wang LW, Prankerd R, Palanisamy UD. 2015; The physicochemical properties of geraniin, a potential antihyperglycemic agent. Pharm Biol. 53:1719–1726. DOI: 10.3109/13880209.2014.1003356. PMID: 25853977.

Article11. Ko H. 2015; Geraniin inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and suppresses A549 lung cancer migration, invasion and anoikis resistance. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 25:3529–3534. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.06.093. PMID: 26169124.

Article12. Yang Y, He B, Zhang X, Yang R, Xia X, Chen L, Li R, Shen Z, Chen P. 2022; Geraniin protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis via regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:2152746. DOI: 10.1155/2022/2152746. PMID: 35222793. PMCID: PMC8881129.

Article13. Chen Z, Zhou H, Huang X, Wang S, Ouyang X, Wang Y, Cao Q, Yang L, Tao Y, Lai H. 2022; Pirfenidone attenuates cardiac hypertrophy against isoproterenol by inhibiting activation of the janus tyrosine kinase-2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK-2/STAT3) signaling pathway. Bioengineered. 13:12772–12782. DOI: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2073145. PMID: 35609321. PMCID: PMC9276057.

Article14. Chen Y, Beng H, Su H, Han F, Fan Z, Lv N, Jovanović A, Tan W. 2019; Isosteviol prevents the development of isoprenalineinduced myocardial hypertrophy. Int J Mol Med. 44:1932–1942. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4342.

Article15. Xu JJ, Li RJ, Zhang ZH, Yang C, Liu SX, Li YL, Chen MW, Wang WW, Zhang GY, Song G, Huang ZR. 2021; Loganin inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy through the JAK2/STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 12:678886. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2021.678886. PMID: 34194329. PMCID: PMC8237232.

Article16. Huang C, Wang P, Xu X, Zhang Y, Gong Y, Hu W, Gao M, Wu Y, Ling Y, Zhao X, Qin Y, Yang R, Zhang W. 2018; The ketone body metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate induces an antidepression-associated ramification of microglia via HDACs inhibition-triggered Akt-small RhoGTPase activation. Glia. 66:256–278. DOI: 10.1002/glia.23241. PMID: 29058362.

Article17. Maron BJ, Maron MS. 2013; Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 381:242–255. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. PMID: 22874472.

Article18. Chung APYS, Gurtu S, Chakravarthi S, Moorthy M, Palanisamy UD. 2018; Geraniin protects high-fat diet-induced oxidative stress in Sprague Dawley rats. Front Nutr. 5:17. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00017. PMID: 29616223. PMCID: PMC5864930.

Article19. Lin K, Wang X, Li J, Zhao P, Xi X, Feng Y, Yin L, Tian J, Li H, Liu X, Yu B. 2022; Anti-atherosclerotic effects of geraniin through the gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway in mice. Phytomedicine. 101:154104. DOI: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154104. PMID: 35461005.

Article20. Liu X, Li J, Peng X, Lv B, Wang P, Zhao X, Yu B. 2016; Geraniin inhibits LPS-induced THP-1 macrophages switching to M1 phenotype via SOCS1/NF-κB pathway. Inflammation. 39:1421–1433. Erratum in: Inflammation. 2021;44:808-809. DOI: 10.1007/s10753-016-0374-7. PMID: 27290719.

Article21. Yin Q, Lu H, Bai Y, Tian A, Yang Q, Wu J, Yang C, Fan TP, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Zheng X, Li Z. 2015; A metabolite of Danshen formulae attenuates cardiac fibrosis induced by isoprenaline, via a NOX2/ROS/p38 pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 172:5573–5585. DOI: 10.1111/bph.13133. PMID: 25766073. PMCID: PMC4667860.

Article22. Leask A. 2015; Getting to the heart of the matter: new insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res. 116:1269–1276. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305381. PMID: 25814687.23. Kakkar R, Lee RT. 2010; Intramyocardial fibroblast myocyte communication. Circ Res. 106:47–57. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207456. PMID: 20056945. PMCID: PMC2805465.

Article24. Rattazzi M, Puato M, Faggin E, Bertipaglia B, Zambon A, Pauletto P. 2003; C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in vascular disease: culprits or passive bystanders? J Hypertens. 21:1787–1803. DOI: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00002. PMID: 14508181.25. Hirota H, Yoshida K, Kishimoto T, Taga T. 1995; Continuous activation of gp130, a signal-transducing receptor component for interleukin 6-related cytokines, causes myocardial hypertrophy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92:4862–4866. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4862. PMID: 7539136. PMCID: PMC41807.

Article26. Cha HN, Choi JH, Kim YW, Kim JY, Ahn MW, Park SY. 2010; Metformin inhibits isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 14:377–384. DOI: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.6.377. PMID: 21311678. PMCID: PMC3034117.

Article27. Al-Rasheed NM, Al-Oteibi MM, Al-Manee RZ, Al-Shareef SA, Al-Rasheed NM, Hasan IH, Mohamad RA, Mahmoud AM. 2015; Simvastatin prevents isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy through modulation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 9:3217–3229. DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S86431. PMID: 26150695. PMCID: PMC4484667.28. Chen X, Zeng S, Zou J, Chen Y, Yue Z, Gao Y, Zhang L, Cao W, Liu P. 2014; Rapamycin attenuated cardiac hypertrophy induced by isoproterenol and maintained energy homeostasis via inhibiting NF-κB activation. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:868753. DOI: 10.1155/2014/868753. PMID: 25045214. PMCID: PMC4089551.29. Kubota T, McTiernan CF, Frye CS, Slawson SE, Lemster BH, Koretsky AP, Demetris AJ, Feldman AM. 1997; Dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res. 81:627–635. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.81.4.627. PMID: 9314845.

Article30. Sun M, Chen M, Dawood F, Zurawska U, Li JY, Parker T, Kassiri Z, Kirshenbaum LA, Arnold M, Khokha R, Liu PP. 2007; Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates cardiac remodeling and ventricular dysfunction after pressure overload state. Circulation. 115:1398–1407. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643585. PMID: 17353445.

Article31. Viswanadha VP, Dhivya V, Beeraka NM, Huang CY, Gavryushova LV, Minyaeva NN, Chubarev VN, Mikhaleva LM, Tarasov VV, Aliev G. 2020; The protective effect of piperine against isoproterenol-induced inflammation in experimental models of myocardial toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 885:173524. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173524. PMID: 32882215.

Article32. Ouyang W, O'Garra A. 2019; IL-10 family cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: from basic science to clinical translation. Immunity. 50:871–891. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.020. PMID: 30995504.

Article33. Verma SK, Garikipati VNS, Krishnamurthy P, Schumacher SM, Grisanti LA, Cimini M, Cheng Z, Khan M, Yue Y, Benedict C, Truongcao MM, Rabinowitz JE, Goukassian DA, Tilley D, Koch WJ, Kishore R. 2017; Interleukin-10 inhibits bone marrow fibroblast progenitor cell-mediated cardiac fibrosis in pressure-overloaded myocardium. Circulation. 136:940–953. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027889. PMID: 28667100. PMCID: PMC5736130.

Article34. Lindberg E, Magnusson Y, Karason K, Andersson B. 2008; Lower levels of the host protective IL-10 in DCM--a feature of autoimmune pathogenesis? Autoimmunity. 41:478–483. DOI: 10.1080/08916930802031645. PMID: 18781475.

Article35. Zhu Y, Li T, Song J, Liu C, Hu Y, Que L, Ha T, Kelley J, Chen Q, Li C, Li Y. 2011; The TIR/BB-loop mimetic AS-1 prevents cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting IL-1R-mediated MyD88-dependent signaling. Basic Res Cardiol. 106:787–799. DOI: 10.1007/s00395-011-0182-z. PMID: 21533832.

Article36. Zhu YF, Wang R, Chen W, Cao YD, Li LP, Chen X. 2021; miR-133a-3p attenuates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through inhibiting pyroptosis activation by targeting IKKε. Acta Histochem. 123:151653. DOI: 10.1016/j.acthis.2020.151653. PMID: 33246224.

Article37. Schafer S, Viswanathan S, Widjaja AA, Lim WW, Moreno-Moral A, DeLaughter DM, Ng B, Patone G, Chow K, Khin E, Tan J, Chothani SP, Ye L, Rackham OJL, Ko NSJ, Sahib NE, Pua CJ, Zhen NTG, Xie C, Wang M, et al. 2017; IL-11 is a crucial determinant of cardiovascular fibrosis. Nature. 552:110–115. DOI: 10.1038/nature24676. PMID: 29160304. PMCID: PMC5807082.

Article38. Moylan S, Berk M, Dean OM, Samuni Y, Williams LJ, O'Neil A, Hayley AC, Pasco JA, Anderson G, Jacka FN, Maes M. 2014; Oxidative & nitrosative stress in depression: why so much stress? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 45:46–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.05.007. PMID: 24858007.

Article39. Sies H, Berndt C, Jones DP. 2017; Oxidative stress. Annu Rev Biochem. 86:715–748. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045037. PMID: 28441057.

Article40. Seddon M, Looi YH, Shah AM. 2007; Oxidative stress and redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart. 93:903–907. DOI: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068270. PMID: 16670100. PMCID: PMC1994416.

Article41. van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA, van der Meer P. 2019; Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: past, present and future. Eur J Heart Fail. 21:425–435. DOI: 10.1002/ejhf.1320. PMID: 30338885. PMCID: PMC6607515.

Article42. Fotino AD, Thompson-Paul AM, Bazzano LA. 2013; Effect of coenzyme Q₁₀ supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 97:268–275. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040741. PMID: 23221577. PMCID: PMC3742297.43. Wollert KC, Drexler H. 2002; Regulation of cardiac remodeling by nitric oxide: focus on cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis. Heart Fail Rev. 7:317–325. DOI: 10.1023/A:1020706316429. PMID: 12379817.

Article44. Kempf T, Wollert KC. 2004; Nitric oxide and the enigma of cardiac hypertrophy. Bioessays. 26:608–615. DOI: 10.1002/bies.20049. PMID: 15170858.

Article45. Madrigal JL, Hurtado O, Moro MA, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Castrillo A, Boscá L, Leza JC. 2002; The increase in TNF-alpha levels is implicated in NF-kappaB activation and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in brain cortex after immobilization stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 26:155–163. DOI: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00292-5. PMID: 11790511.

Article46. Inoue N, Watanabe M, Ishido N, Kodu A, Maruoka H, Katsumata Y, Hidaka Y, Iwatani Y. 2016; Involvement of genes encoding apoptosis regulatory factors (FAS, FASL, TRAIL, BCL2, TNFR1 and TNFR2) in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Hum Immunol. 77:944–951. DOI: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.07.232. PMID: 27458112.

Article47. Xie C, Yi J, Lu J, Nie M, Huang M, Rong J, Zhu Z, Chen J, Zhou X, Li B, Chen H, Lu N, Shu X. 2018; N-acetylcysteine reduces ROS-mediated oxidative DNA damage and PI3K/Akt pathway activation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018:1874985. DOI: 10.1155/2018/1874985. PMID: 29854076. PMCID: PMC5944265.

Article48. Konstantinidis K, Whelan RS, Kitsis RN. 2012; Mechanisms of cell death in heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 32:1552–1562. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224915. PMID: 22596221. PMCID: PMC3835661.

Article49. Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Bátkai S, Kashiwaya Y, Haskó G, Liaudet L, Szabó C, Pacher P. 2009; Role of superoxide, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite in doxorubicin-induced cell death in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 296:H1466–H1483. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00795.2008. PMID: 19286953. PMCID: PMC2685360.

Article50. Qi J, Wang F, Yang P, Wang X, Xu R, Chen J, Yuan Y, Lu Z, Duan J. 2018; Mitochondrial fission is required for angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis mediated by a Sirt1-p53 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 9:176. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00176. PMID: 29593530. PMCID: PMC5854948.

Article51. Yu W, Sun H, Zha W, Cui W, Xu L, Min Q, Wu J. 2017; Apigenin attenuates adriamycin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:2590676. DOI: 10.1155/2017/2590676. PMID: 28684964. PMCID: PMC5480054.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Altered delayed rectifier K+ current of rabbit coronary arterial myocytes in isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy

- Metformin Inhibits Isoproterenol-induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Mice

- The alteration of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in coronary arterial smooth muscle cells isolated from isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rabbit

- Cardiac Myocyte Cell Death in Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Rats

- Resveratrol attenuates aging-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in the rat heart