Cancer Res Treat.

2025 Jan;57(1):280-288. 10.4143/crt.2024.360.

Factors Affecting Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions and Changes in Clinical Practice after Enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment (LST) Decision Act: A Tertiary Hospital Experience in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Hematology and Oncology, Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Cancer Institute of Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2564600

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2024.360

Abstract

- Purpose

In Korea, the Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment (LST) was implemented on February 4, 2018. We aimed to investigate relevant factors and clinical changes associated with LST decisions after law enforcement.

Materials and Methods

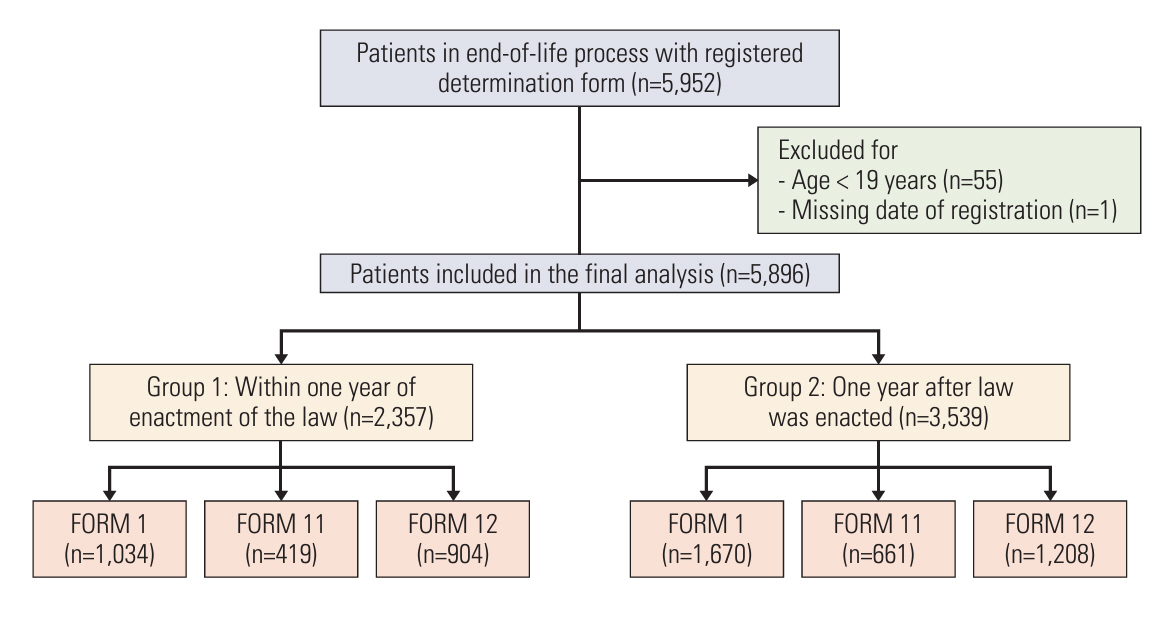

This single-center retrospective study included patients who completed LST documents using legal forms at Asan Medical Center from February 5, 2018, to June 30, 2020.

Results

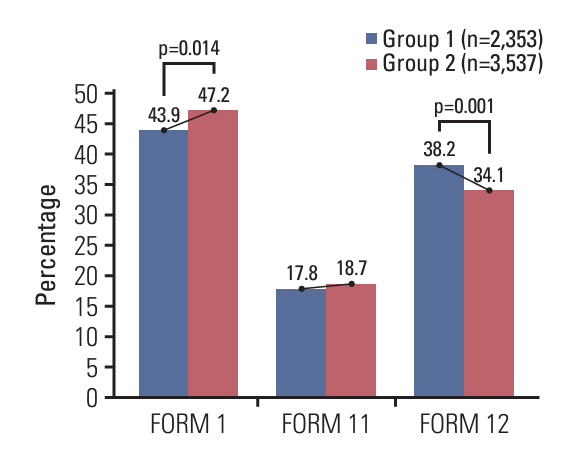

5,896 patients completed LST documents, of which 2,704 (45.8%) signed the documents in person, while family members of 3,192 (54%) wrote the documents on behalf of the patients. Comparing first year and following year of implementation of the act, the self-documentation rate increased (43.9% to 47.2%, p=0.014). Moreover, the number of LST decisions made during or after intensive care unit admission decreased (37.8% vs. 35.2%, p=0.045), and the completion rate of LST documents during chemotherapy increased (6.6% vs. 8.9%, p=0.001). In multivariate analysis, age < 65 (odds ratio [OR], 1.724; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.538 to 1.933; p < 0.001), unmarried status (OR, 1.309; 95% CI, 1.097 to 1.561; p=0.003), palliative care consultation (OR, 1.538; 95% CI, 1.340 to 1.765; p < 0.001), malignancy (OR, 1.864; 95% CI, 1.628 to 2.133; p < 0.001), and changes in timing on the first year versus following year (OR, 1.124; 95% CI, 1.003 to 1.260; p=0.045) were related to a higher self-documentation rate.

Conclusion

Age < 65 years, unmarried status, malignancy, and referral to a palliative care team were associated with patients making LST decisions themselves. Furthermore, the subject and timing of LST decisions have changed with the LST act.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, Clark MM; Mayo Clinic Cancer Center Quality of Life Working Group. Maintaining quality of life at the end of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000; 75:1305–10.2. Emanuel EJ. Palliative and end-of-life care. In : Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 21st ed. New York: McGraw Hill;2022. p. 72–89.3. Rietjens JA, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017; 18:e543–51.4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.. NCCN guidelines: palliative care [Internet]. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network;2024. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf.5. Clayer MT. Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust. 2007; 187:478.6. Kaasa S, Loge JH. Quality of life in palliative care: principles and practice. Palliat Med. 2003; 17:11–20.7. Garrido MM, Balboni TA, Maciejewski PK, Bao Y, Prigerson HG. Quality of life and cost of care at the end of life: the role of advance directives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015; 49:828–35.8. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014; 28:1000–25.9. Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med. 2016; 19:8–15.10. Cheng SY, Chen CY, Chiu TY. Advances of hospice palliative care in Taiwan. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016; 19:292–5.11. Kim HS, Hong YS. Hospice palliative care in South Korea: past, present, and future. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016; 19:99–108.12. Lee JK, Keam B, An AR, Kim TM, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. Surrogate decision-making in Korean patients with advanced cancer: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21:183–90.13. Kim DY, Lee KE, Nam EM, Lee HR, Lee KW, Kim JH, et al. Do-not-resuscitate orders for terminal patients with cancer in teaching hospitals of Korea. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10:1153–8.14. Oh DY, Kim JH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, et al. CPR or DNR? End-of-life decision in Korean cancer patients: a single center’s experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006; 14:103–8.15. Choi Y, Keam B, Kim TM, Lee SH, Kim DW, Heo DS. Cancer treatment near the end-of-life becomes more aggressive: changes in trend during 10 years at a single institute. Cancer Res Treat. 2015; 47:555–63.16. Act on Hospice-palliative Care and Life-sustaining Treatment Decision-making. No. 14013 (Feb 3, 2016).17. Kim CG. Hospice and palliative care policy in Korea. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017; 20:8–17.18. Kim JS, Yoo SH, Choi W, Kim Y, Hong J, Kim MS, et al. Implication of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act on End-of-Life Care for Korean Terminal Patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52:917–24.19. Kim H, Im HS, Lee KO, Min YJ, Jo JC, Choi Y, et al. Changes in decision-making process for life-sustaining treatment in patients with advanced cancer after the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions-Making Act. BMC Palliat Care. 2021; 20:63.20. Won YW, Kim HJ, Kwon JH, Lee HY, Baek SK, Kim YJ, et al. Life-sustaining treatment states in Korean cancer patients after enforcement of Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:908–16.21. Kim D, Yoo SH, Seo S, Lee HJ, Kim MS, Shin SJ, et al. Analysis of cancer patient decision-making and health service utilization after enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2022; 54:20–9.22. Park SY, Lee B, Seon JY, Oh IH. A national study of life-sustaining treatments in South Korea: what factors affect decision-making? Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:593–600.23. Lee HY, Kim HJ, Kwon JH, Baek SK, Won YW, Kim YJ, et al. The situation of life-sustaining treatment one year after enforcement of the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End-of-Life in Korea: data of national agency for management of life-sustaining treatment. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:897–907.24. Schlick CJR, Bentrem DJ. Timing of palliative care: when to call for a palliative care consult. J Surg Oncol. 2019; 120:30–4.25. Jung Y, Yeom HE, Lee NR. The effects of counseling about death and dying on perceptions, preparedness, and anxiety regarding death among family caregivers caring for hospice patients: a pilot study. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021; 24:46–55.26. Mori M, Morita T. End-of-life decision-making in Asia: a need for in-depth cultural consideration. Palliat Med. 2020; 34:NP4–5.27. Kim HA, Park JY. Changes in life-sustaining treatment in terminally ill cancer patients after signing a do-not-resuscitate order. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017; 20:93–9.28. van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2003; 362:345–50.29. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, Kent S, Kim J, Herbst N, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017; 36:1244–51.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Implication of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act on End-of-Life Care for Korean Terminal Patients

- Difficulties Doctors Experience during Life-Sustaining Treatment Discussion after Enactment of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Awareness of good death, perception of life-sustaining treatment decision, and changes in nursing activities after decision to discontinue life-sustaining treatment among nurses in intensive care units at tertiary general hospitals

- Well-Dying: Assisted Justice Act as a Dignified and Happy ‘Right to Self-Determination’

- Reversals in Decisions about Life-Sustaining Treatment and Associated Factors among Older Patients with Terminal Stage of Cardiopulmonary Disease