Diabetes Metab J.

2024 Jan;48(1):97-111. 10.4093/dmj.2022.0367.

DWN12088, A Prolyl-tRNA Synthetase Inhibitor, Alleviates Hepatic Injury in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine and Research Institute of Metabolism and Inflammation, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea

- 2Division of Research Program, Scripps Korea Antibody Institute, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3Drug Discovery Center, Daewoong Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2551266

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0367

Abstract

- Background

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a liver disease caused by obesity that leads to hepatic lipoapoptosis, resulting in fibrosis and cirrhosis. However, the mechanism underlying NASH is largely unknown, and there is currently no effective therapeutic agent against it. DWN12088, an agent used for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, is a selective prolyl-tRNA synthetase (PRS) inhibitor that suppresses the synthesis of collagen. However, the mechanism underlying the hepatoprotective effect of DWN12088 is not clear. Therefore, we investigated the role of DWN12088 in NASH progression.

Methods

Mice were fed a chow diet or methionine-choline deficient (MCD)-diet, which was administered with DWN12088 or saline by oral gavage for 6 weeks. The effects of DWN12088 on NASH were evaluated by pathophysiological examinations, such as real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, immunoblotting, biochemical analysis, and immunohistochemistry. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of hepatic injury were assessed by in vitro cell culture.

Results

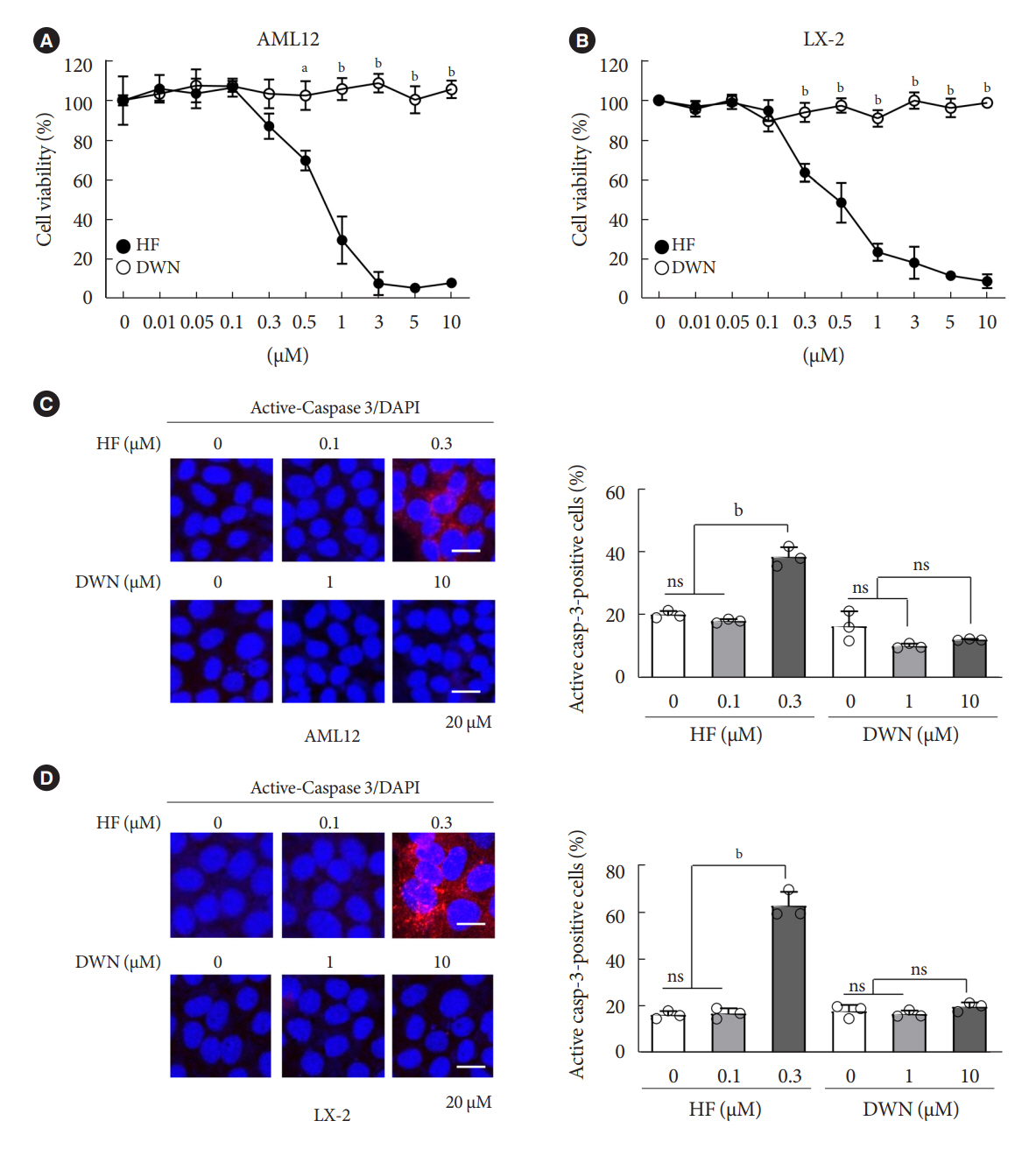

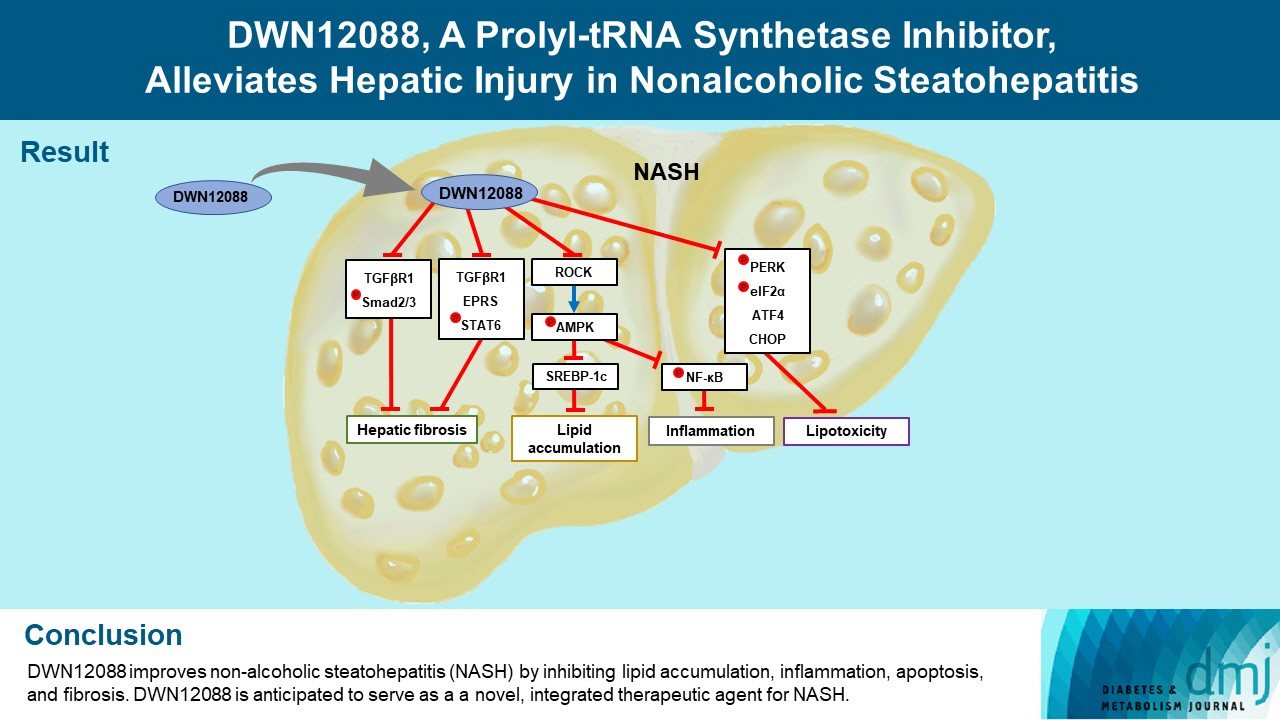

DWN12088 attenuated palmitic acid (PA)-induced lipid accumulation and lipoapoptosis by downregulating the Rho-kinase (ROCK)/AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)/α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α)/activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)/C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) signaling cascades. PA increased but DWN12088 inhibited the phosphorylation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65 (Ser536, Ser276) and the expression of proinflammatory genes. Moreover, the DWN12088 inhibited transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)-induced pro-fibrotic gene expression by suppressing TGFβ receptor 1 (TGFβR1)/Smad2/3 and TGFβR1/glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) axis signaling. In the case of MCD-diet-induced NASH, DWN12088 reduced hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and lipoapoptosis and prevented the progression of fibrosis.

Conclusion

Our findings provide new insights about DWN12088, namely that it plays an important role in the overall improvement of NASH. Hence, DWN12088 shows great potential to be developed as a new integrated therapeutic agent for NASH.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:960–7.2. Williamson RM, Price JF, Glancy S, Perry E, Nee LD, Hayes PC, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for hepatic steatosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34:1139–44.3. Hazlehurst JM, Woods C, Marjot T, Cobbold JF, Tomlinson JW. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metabolism. 2016; 65:1096–108.4. Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001; 414:782–7.5. Takaki A, Kawai D, Yamamoto K. Multiple hits, including oxidative stress, as pathogenesis and treatment target in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Int J Mol Sci. 2013; 14:20704–28.6. Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology. 2010; 52:774–88.7. Luedde T, Kaplowitz N, Schwabe RF. Cell death and cell death responses in liver disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology. 2014; 147:765–83.8. Ferre P, Foufelle F. SREBP-1c transcription factor and lipid homeostasis: clinical perspective. Horm Res. 2007; 68:72–82.9. Bi Y, Wu W, Shi J, Liang H, Yin W, Chen Y, et al. Role for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c activation in mediating skeletal muscle insulin resistance via repression of rat insulin receptor substrate-1 transcription. Diabetologia. 2014; 57:592–602.10. Commerford SR, Peng L, Dube JJ, O’Doherty RM. In vivo regulation of SREBP-1c in skeletal muscle: effects of nutritional status, glucose, insulin, and leptin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004; 287:R218–27.11. Wu W, Tang S, Shi J, Yin W, Cao S, Bu R, et al. Metformin attenuates palmitic acid-induced insulin resistance in L6 cells through the AMP-activated protein kinase/sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2015; 35:1734–40.12. Tang S, Wu W, Tang W, Ge Z, Wang H, Hong T, et al. Suppression of Rho-kinase 1 is responsible for insulin regulation of the AMPK/SREBP-1c pathway in skeletal muscle cells exposed to palmitate. Acta Diabetol. 2017; 54:635–44.13. Unger RH, Orci L. Lipoapoptosis: its mechanism and its diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002; 1585:202–12.14. Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Angulo P, Taniai M, Burgart LJ, Lindor KD, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2003; 125:437–43.15. Borradaile NM, Han X, Harp JD, Gale SE, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Disruption of endoplasmic reticulum structure and integrity in lipotoxic cell death. J Lipid Res. 2006; 47:2726–37.16. Wei Y, Wang D, Topczewski F, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acids induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis independently of ceramide in liver cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006; 291:E275–81.17. Wei Y, Wang D, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acid-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis are augmented by trans-10, cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid in liver cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007; 303:105–13.18. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999; 397:271–4.19. McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001; 21:1249–59.20. Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 20:436–43.21. Ziegler S, Pries V, Hedberg C, Waldmann H. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: finding the needle in the haystack. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013; 52:2744–92.22. Kang YB, Mallikarjuna PR, Fabian DA, Gorajana A, Lim CL, Tan EL. Bioactive molecules: current trends in discovery, synthesis, delivery and testing. IeJSME. 2013; 7(Suppl 1):S32–46.23. Halevy O, Nagler A, Levi-Schaffer F, Genina O, Pines M. Inhibition of collagen type I synthesis by skin fibroblasts of graft versus host disease and scleroderma patients: effect of halofuginone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996; 52:1057–63.24. Turgeman T, Hagai Y, Huebner K, Jassal DS, Anderson JE, Genin O, et al. Prevention of muscle fibrosis and improvement in muscle performance in the mdx mouse by halofuginone. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008; 18:857–68.25. Luo Y, Xie X, Luo D, Wang Y, Gao Y. The role of halofuginone in fibrosis: more to be explored? J Leukoc Biol. 2017; 102:1333–45.26. Keller TL, Zocco D, Sundrud MS, Hendrick M, Edenius M, Yum J, et al. Halofuginone and other febrifugine derivatives inhibit prolyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat Chem Biol. 2012; 8:311–7.27. Pines M, Spector I. Halofuginone: the multifaceted molecule. Molecules. 2015; 20:573–94.28. Kershenobich D, Fierro FJ, Rojkind M. The relationship between the free pool of proline and collagen content in human liver cirrhosis. J Clin Invest. 1970; 49:2246–9.29. Pines M, Snyder D, Yarkoni S, Nagler A. Halofuginone to treat fibrosis in chronic graft-versus-host disease and scleroderma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003; 9:417–25.30. ClinicalTrials.gov. Clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DWN12088 in patients with IPF. Available from: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05389215 (2023 Apr 26).31. Zeng X, Zhu M, Liu X, Chen X, Yuan Y, Li L, et al. Oleic acid ameliorates palmitic acid induced hepatocellular lipotoxicity by inhibition of ER stress and pyroptosis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2020; 17:11.32. Lee DK, Kim JH, Kim J, Choi S, Park M, Park W, et al. REDD-1 aggravates endotoxin-induced inflammation via atypical NFκB activation. FASEB J. 2018; 32:4585–99.33. Kim JH, Na HJ, Kim CK, Kim JY, Ha KS, Lee H, et al. The nonprovitamin A carotenoid, lutein, inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through redox-based regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/Akt and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase pathways: role of H(2)O(2) in NF-kappaB activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 45:885–96.34. Nelson EF, Huang CW, Ewel JM, Chang AA, Yuan C. Halofuginone down-regulates Smad3 expression and inhibits the TGFbeta-induced expression of fibrotic markers in human corneal fibroblasts. Mol Vis. 2012; 18:479–87.35. McGaha TL, Phelps RG, Spiera H, Bona C. Halofuginone, an inhibitor of type-I collagen synthesis and skin sclerosis, blocks transforming-growth-factor-beta-mediated Smad3 activation in fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2002; 118:461–70.36. Fabregat I, Moreno-Caceres J, Sanchez A, Dooley S, Dewidar B, Giannelli G, et al. TGF-β signalling and liver disease. FEBS J. 2016; 283:2219–32.37. Song DG, Kim D, Jung JW, Nam SH, Kim JE, Kim HJ, et al. Glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase induces fibrotic extracellular matrix via both transcriptional and translational mechanisms. FASEB J. 2019; 33:4341–54.38. Salminen A, Hyttinen JM, Kaarniranta K. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-κB signaling and inflammation: impact on healthspan and lifespan. J Mol Med (Berl). 2011; 89:667–76.39. Cho H, Wu M, Zhang L, Thompson R, Nath A, Chan C. Signaling dynamics of palmitate-induced ER stress responses mediated by ATF4 in HepG2 cells. BMC Syst Biol. 2013; 7:9.40. Lee CH, Cho M, Kim JM, Lee JH, Kim DW, Park MY, et al. A first-in-class PRS inhibitor, DWN12088, as a novel therapeutic agent for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020; 202:A2786.41. Chen GQ, Tang CF, Shi XK, Lin CY, Fatima S, Pan XH, et al. Halofuginone inhibits colorectal cancer growth through suppression of Akt/mTORC1 signaling and glucose metabolism. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:24148–62.42. Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005; 30:43–52.43. Kim Y, Sundrud MS, Zhou C, Edenius M, Zocco D, Powers K, et al. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibition activates a pathway that branches from the canonical amino acid response in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117:8900–11.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pathology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- Transcriptome analysis reveals stimulus-specific functions of glutamylprolyl-tRNA synthetase

- The role of hepatic macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

- The Diagnosis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease