Korean J Transplant.

2023 Dec;37(4):229-240. 10.4285/kjt.23.0055.

Regulatory macrophages in solid organ xenotransplantation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2550234

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/kjt.23.0055

Abstract

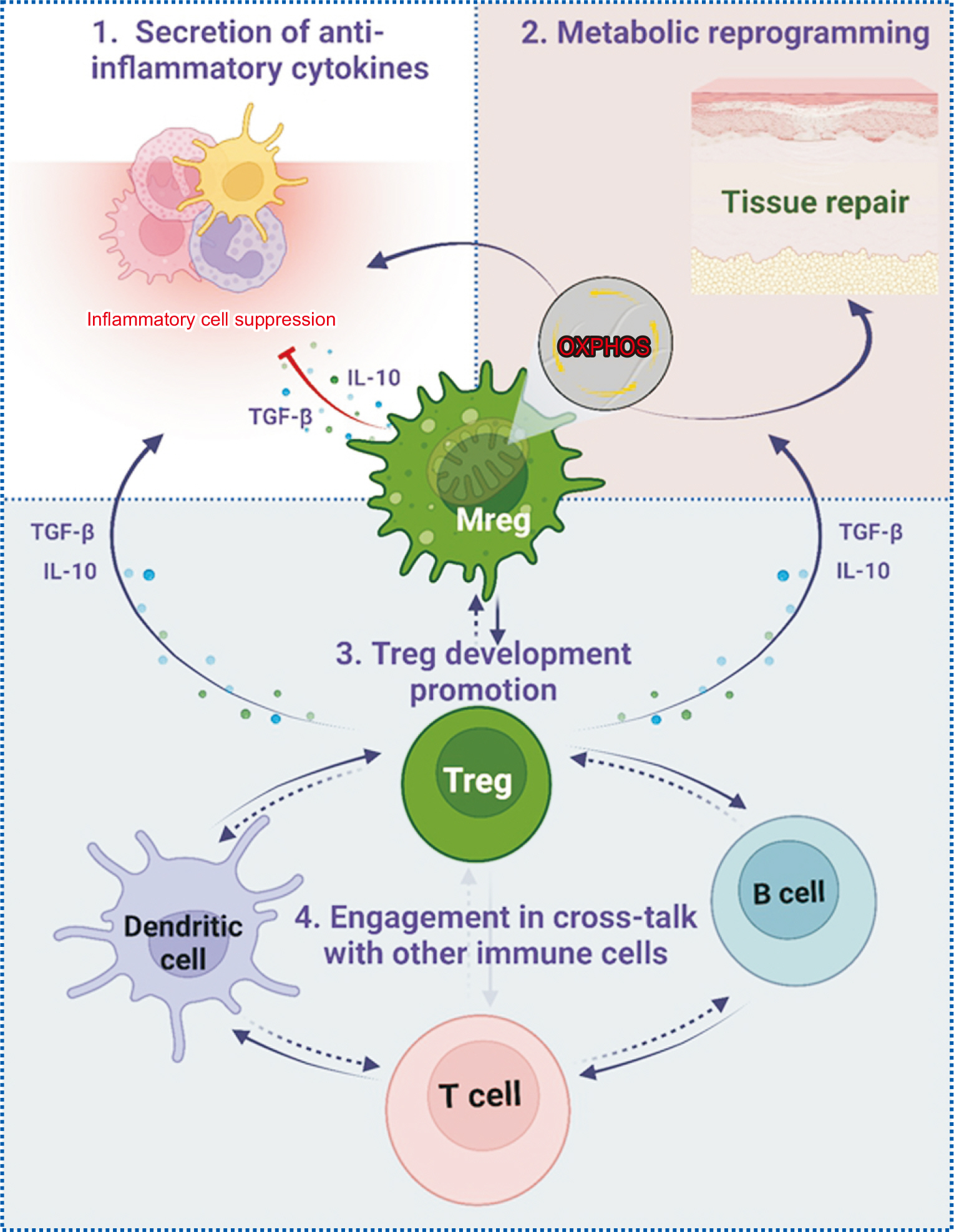

- Due to a critical organ shortage, pig organs are being explored for use in transplantation. Differences between species, particularly in cell surface glycans, can trigger elevated immune responses in xenotransplantation. To mitigate the risk of hyperacute rejection, genetically modified pigs have been developed that lack certain glycans and express human complement inhibitors. Nevertheless, organs from these pigs may still provoke stronger inflammatory and innate immune reactions than allotransplants. Dysregulation of coagulation and persistent inflammation remain obstacles in the transplantation of pig organs into primates. Regulatory macrophages (Mregs), known for their anti-inflammatory properties, could offer a potential solution. Mregs secrete interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor beta, thereby suppressing immune responses and promoting the development of regulatory T cells. These Mregs are typically induced via the stimulation of monocytes or macrophages with macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interferon gamma, and they conspicuously express the stable marker dehydrogenase/reductase 9. Consequently, understanding the precise mechanisms governing Mreg generation, stability, and immunomodulation could pave the way for the therapeutic use of Mregs generated in vitro. This approach has the potential to reduce the required dosages and durations of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications in preclinical and clinical settings.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Galili U. 2005; The alpha-gal epitope and the anti-Gal antibody in xenotransplantation and in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 83:674–86. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01366.x. PMID: 16266320.2. Cooper DK, Ekser B, Tector AJ. 2015; Immunobiological barriers to xenotransplantation. Int J Surg. 23(Pt B):211–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.068. PMID: 26159291. PMCID: PMC4684773.3. Denner J. 2014; Xenotransplantation-progress and problems: a review. J Transplant Technol Res. 4:1000133. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0991.1000133.4. Burlak C, Bern M, Brito AE, Isailovic D, Wang ZY, Estrada JL, et al. 2013; N-linked glycan profiling of GGTA1/CMAH knockout pigs identifies new potential carbohydrate xenoantigens. Xenotransplantation. 20:277–91. DOI: 10.1111/xen.12047. PMID: 24033743. PMCID: PMC4593510.5. Nanno Y, Shajahan A, Sonon RN, Azadi P, Hering BJ, Burlak C. 2020; High-mannose type N-glycans with core fucosylation and complex-type N-glycans with terminal neuraminic acid residues are unique to porcine islets. PLoS One. 15:e0241249. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241249. PMID: 33170858. PMCID: PMC7654812.6. Choe HM, Luo ZB, Xuan MF, Quan BH, Kang JD, Oh MJ, et al. Sialylation and fucosylation changes of cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) and glycoprotein, alpha1, 3-galactosyltransferase (GGTA1) knockout pig erythrocyte membranes. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.07.240846. cited 2023 Aug 23. DOI: 10.1101/2020.08.07.240846.7. Yeh P, Ezzelarab M, Bovin N, Hara H, Long C, Tomiyama K, et al. 2010; Investigation of potential carbohydrate antigen targets for human and baboon antibodies. Xenotransplantation. 17:197–206. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00579.x. PMID: 20636540.8. Ezzelarab MB, Cooper DK. 2015; Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR): a new paradigm in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation? Int J Surg. 23(Pt B):301–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.643. PMID: 26209584. PMCID: PMC4684785.9. Garcia MR, Ledgerwood L, Yang Y, Xu J, Lal G, Burrell B, et al. 2010; Monocytic suppressive cells mediate cardiovascular transplantation tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 120:2486–96. DOI: 10.1172/JCI41628. PMID: 20551515. PMCID: PMC2898596.10. Ochando J, Conde P, Bronte V. 2015; Monocyte-derived suppressor cells in transplantation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2:176–83. DOI: 10.1007/s40472-015-0054-9. PMID: 26301174. PMCID: PMC4541698.11. Biswas SK, Mantovani A. 2010; Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 11:889–96. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1937. PMID: 20856220.12. Hutchinson JA, Riquelme P, Sawitzki B, Tomiuk S, Miqueu P, Zuhayra M, et al. 2011; Cutting edge: immunological consequences and trafficking of human regulatory macrophages administered to renal transplant recipients. J Immunol. 187:2072–8. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100762. PMID: 21804023.13. Ezzelarab M, Hara H, Busch J, Rood PP, Zhu X, Ibrahim Z, et al. 2006; Antibodies directed to pig non-Gal antigens in naïve and sensitized baboons. Xenotransplantation. 13:400–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00320.x. PMID: 16925663.14. Baumann BC, Stussi G, Huggel K, Rieben R, Seebach JD. 2007; Reactivity of human natural antibodies to endothelial cells from Galalpha(1,3)Gal-deficient pigs. Transplantation. 83:193–201. DOI: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250478.00567.e5. PMID: 17264816.15. Pierson RN 3rd, Dorling A, Ayares D, Rees MA, Seebach JD, Fishman JA, et al. 2009; Current status of xenotransplantation and prospects for clinical application. Xenotransplantation. 16:263–80. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00534.x. PMID: 19796067. PMCID: PMC2866107.16. Lin CC, Chen D, McVey JH, Cooper DK, Dorling A. 2008; Expression of tissue factor and initiation of clotting by human platelets and monocytes after incubation with porcine endothelial cells. Transplantation. 86:702–9. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818410a3. PMID: 18791452. PMCID: PMC2637773.17. Zelaya H, Rothmeier AS, Ruf W. 2018; Tissue factor at the crossroad of coagulation and cell signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 16:1941–52. DOI: 10.1111/jth.14246. PMID: 30030891.18. Bühler L, Basker M, Alwayn IP, Goepfert C, Kitamura H, Kawai T, et al. 2000; Coagulation and thrombotic disorders associated with pig organ and hematopoietic cell transplantation in nonhuman primates. Transplantation. 70:1323–31. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-200011150-00010. PMID: 11087147.19. Kuwaki K, Tseng YL, Dor FJ, Shimizu A, Houser SL, Sanderson TM, et al. 2005; Heart transplantation in baboons using alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene- knockout pigs as donors: initial experience. Nat Med. 11:29–31. DOI: 10.1038/nm1171. PMID: 15619628.20. Siegel JB, Grey ST, Lesnikoski BA, Kopp CW, Soares M, Esch JS, et al. 1997; Xenogeneic endothelial cells activate human prothrombin. Transplantation. 64:888–96. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-199709270-00017. PMID: 9326416.21. Roussel JC, Moran CJ, Salvaris EJ, Nandurkar HH, d'Apice AJ, Cowan PJ. 2008; Pig thrombomodulin binds human thrombin but is a poor cofactor for activation of human protein C and TAFI. Am J Transplant. 8:1101–12. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02210.x. PMID: 18444940.22. Cowan PJ, d'Apice AJ. 2009; Complement activation and coagulation in xenotransplantation. Immunol Cell Biol. 87:203–8. DOI: 10.1038/icb.2008.107. PMID: 19153592.23. Pareti FI, Mazzucato M, Bottini E, Mannucci PM. 1992; Interaction of porcine von Willebrand factor with the platelet glycoproteins Ib and IIb/IIIa complex. Br J Haematol. 82:81–6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb04597.x. PMID: 1419806.24. Gawaz M. 2004; Role of platelets in coronary thrombosis and reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 61:498–511. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.036. PMID: 14962480.25. Antonioli L, Pacher P, Vizi ES, Haskó G. 2013; CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 19:355–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.005. PMID: 23601906. PMCID: PMC3674206.26. Shimizu A, Hisashi Y, Kuwaki K, Tseng YL, Dor FJ, Houser SL, et al. 2008; Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with humoral rejection of cardiac xenografts from alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs in baboons. Am J Pathol. 172:1471–81. DOI: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070672. PMID: 18467706. PMCID: PMC2408408.27. Khalpey Z, Yuen AH, Kalsi KK, Kochan Z, Karbowska J, Slominska EM, et al. 2005; Loss of ecto-5'nucleotidase from porcine endothelial cells after exposure to human blood: Implications for xenotransplantation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1741:191–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.03.008. PMID: 15955461.28. Wheeler DG, Joseph ME, Mahamud SD, Aurand WL, Mohler PJ, Pompili VJ, et al. 2012; Transgenic swine: expression of human CD39 protects against myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 52:958–61. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.002. PMID: 22269791. PMCID: PMC3327755.29. Zecher D, van Rooijen N, Rothstein DM, Shlomchik WD, Lakkis FG. 2009; An innate response to allogeneic nonself mediated by monocytes. J Immunol. 183:7810–6. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902194. PMID: 19923456.30. Oberbarnscheidt MH, Zeng Q, Li Q, Dai H, Williams AL, Shlomchik WD, et al. 2014; Non-self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 124:3579–89. DOI: 10.1172/JCI74370. PMID: 24983319. PMCID: PMC4109551.31. Ezzelarab MB, Ekser B, Azimzadeh A, Lin CC, Zhao Y, Rodriguez R, et al. 2015; Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients precedes activation of coagulation. Xenotransplantation. 22:32–47. DOI: 10.1111/xen.12133. PMID: 25209710. PMCID: PMC4329078.32. Iwase H, Ekser B, Zhou H, Liu H, Satyananda V, Humar R, et al. 2015; Further evidence for sustained systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR). Xenotransplantation. 22:399–405. DOI: 10.1111/xen.12182. PMID: 26292982. PMCID: PMC4575631.33. Li T, Lee W, Hara H, Long C, Ezzelarab M, Ayares D, et al. 2017; An investigation of extracellular histones in pig-to-baboon organ xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 101:2330–9. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001676. PMID: 28157735. PMCID: PMC5856196.34. Iwase H, Liu H, Li T, Zhang Z, Gao B, Hara H, et al. 2017; Therapeutic regulation of systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients. Xenotransplantation. 24:e12296. DOI: 10.1111/xen.12296. PMID: 28294424. PMCID: PMC5397335.35. Kim JY. 2019; Macrophages in xenotransplantation. Korean J Transplant. 33:74–82. DOI: 10.4285/jkstn.2019.33.4.74. PMID: 35769982. PMCID: PMC9188951.36. Ishihara K, Hirano T. 2002; IL-6 in autoimmune disease and chronic inflammatory proliferative disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 13:357–68. DOI: 10.1016/S1359-6101(02)00027-8. PMID: 12220549.37. Hunter CA, Jones SA. 2015; IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 16:448–57. DOI: 10.1038/ni.3153. PMID: 25898198.38. Jones SA, Jenkins BJ. 2018; Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 18:773–89. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-018-0066-7. PMID: 30254251.39. Lin CC, Ezzelarab M, Shapiro R, Ekser B, Long C, Hara H, et al. 2010; Recipient tissue factor expression is associated with consumptive coagulopathy in pig-to-primate kidney xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 10:1556–68. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03147.x. PMID: 20642682. PMCID: PMC2914318.40. Chu AJ. 2011; Tissue factor, blood coagulation, and beyond: an overview. Int J Inflam. 2011:367284. DOI: 10.4061/2011/367284. PMID: 21941675. PMCID: PMC3176495.41. Wu J, Stevenson MJ, Brown JM, Grunz EA, Strawn TL, Fay WP. 2008; C-reactive protein enhances tissue factor expression by vascular smooth muscle cells: mechanisms and in vivo significance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 28:698–704. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160903. PMID: 18276908.42. Strukova S. 2006; Blood coagulation-dependent inflammation. Coagulation-dependent inflammation and inflammation-dependent thrombosis. Front Biosci. 11:59–80. DOI: 10.2741/1780. PMID: 16146714.43. Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. 1992; Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 176:287–92. DOI: 10.1084/jem.176.1.287. PMID: 1613462. PMCID: PMC2119288.44. Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. 2004; The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 25:677–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. PMID: 15530839.45. Curi R, Mendes R, Crispin LA, Norata GD, Sampaio SC, Newsholme P. 2017; A past and present overview of macrophage metabolism and functional outcomes. Clin Sci (Lond). 131:1329–42. DOI: 10.1042/CS20170220. PMID: 28592702.46. Ip WK, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, Medzhitov R. 2017; Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science. 356:513–9. DOI: 10.1126/science.aal3535. PMID: 28473584. PMCID: PMC6260791.47. Nau GJ, Richmond JF, Schlesinger A, Jennings EG, Lander ES, Young RA. 2002; Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99:1503–8. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.022649799. PMID: 11805289. PMCID: PMC122220.48. Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. 2006; Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 177:7303–11. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. PMID: 17082649.49. Yao Y, Xu XH, Jin L. 2019; Macrophage polarization in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Front Immunol. 10:792. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00792. PMID: 31037072. PMCID: PMC6476302.50. Giacomelli R, Ruscitti P, Alvaro S, Ciccia F, Liakouli V, Di Benedetto P, et al. 2016; IL-1β at the crossroad between rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes: may we kill two birds with one stone? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 12:849–55. DOI: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1168293. PMID: 26999417.51. Di Benedetto P, Ruscitti P, Vadasz Z, Toubi E, Giacomelli R. 2019; Macrophages with regulatory functions, a possible new therapeutic perspective in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 18:102369. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102369. PMID: 31404701.52. Zhang F, Zhang J, Cao P, Sun Z, Wang W. 2021; The characteristics of regulatory macrophages and their roles in transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 91:107322. DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107322. PMID: 33418238.53. Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. 2013; Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 229:176–85. DOI: 10.1002/path.4133. PMID: 23096265.54. Martinez FO, Gordon S. 2014; The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 6:13. DOI: 10.12703/P6-13. PMID: 24669294. PMCID: PMC3944738.55. Sudan B, Wacker MA, Wilson ME, Graff JW. 2015; A systematic approach to identify markers of distinctly activated human macrophages. Front Immunol. 6:253. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00253. PMID: 26074920. PMCID: PMC4445387.56. Hesketh M, Sahin KB, West ZE, Murray RZ. 2017; Macrophage phenotypes regulate scar formation and chronic wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 18:1545. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18071545. PMID: 28714933. PMCID: PMC5536033.57. Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Staels B. 2014; Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev. 262:153–66. DOI: 10.1111/imr.12218. PMID: 25319333.58. De Paoli F, Staels B, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G. 2014; Macrophage phenotypes and their modulation in atherosclerosis. Circ J. 78:1775–81. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0621. PMID: 24998279.59. Wynn TA, Vannella KM. 2016; Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. 44:450–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015. PMID: 26982353. PMCID: PMC4794754.60. Gensel JC, Zhang B. 2015; Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 1619:1–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.045. PMID: 25578260.61. Graff JW, Dickson AM, Clay G, McCaffrey AP, Wilson ME. 2012; Identifying functional microRNAs in macrophages with polarized phenotypes. J Biol Chem. 287:21816–25. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327031. PMID: 22549785. PMCID: PMC3381144.62. Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, et al. 2018; Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 233:6425–40. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.26429. PMID: 29319160.63. Ito I, Asai A, Suzuki S, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F. 2017; M2b macrophage polarization accompanied with reduction of long noncoding RNA GAS5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 493:170–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.053. PMID: 28917839.64. Wilcock DM. 2012; A changing perspective on the role of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012:495243. DOI: 10.1155/2012/495243. PMID: 22844636. PMCID: PMC3403314.65. Ohlsson SM, Linge CP, Gullstrand B, Lood C, Johansson A, Ohlsson S, et al. 2014; Serum from patients with systemic vasculitis induces alternatively activated macrophage M2c polarization. Clin Immunol. 152:10–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.02.016. PMID: 24631966.66. Schulert GS, Fall N, Harley JB, Shen N, Lovell DJ, Thornton S, et al. 2016; Monocyte microRNA expression in active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis implicates microRNA-125a-5p in polarized monocyte phenotypes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68:2300–13. DOI: 10.1002/art.39694. PMID: 27014994. PMCID: PMC5001902.67. Orme J, Mohan C. 2012; Macrophage subpopulations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Discov Med. 13:151–8.68. MacParland SA, Tsoi KM, Ouyang B, Ma XZ, Manuel J, Fawaz A, et al. 2017; Phenotype determines nanoparticle uptake by human macrophages from liver and blood. ACS Nano. 11:2428–43. DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b06245. PMID: 28040885.69. Fujiwara Y, Hizukuri Y, Yamashiro K, Makita N, Ohnishi K, Takeya M, et al. 2016; Guanylate-binding protein 5 is a marker of interferon-γ-induced classically activated macrophages. Clin Transl Immunology. 5:e111. DOI: 10.1038/cti.2016.59. PMID: 27990286. PMCID: PMC5133363.70. Rőszer T. 2015; Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:816460. DOI: 10.1155/2015/816460. PMID: 26089604. PMCID: PMC4452191.71. Wang LX, Zhang SX, Wu HJ, Rong XL, Guo J. 2019; M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 106:345–58. DOI: 10.1002/JLB.3RU1018-378RR. PMID: 30576000. PMCID: PMC7379745.72. Zizzo G, Hilliard BA, Monestier M, Cohen PL. 2012; Efficient clearance of early apoptotic cells by human macrophages requires M2c polarization and MerTK induction. J Immunol. 189:3508–20. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200662. PMID: 22942426. PMCID: PMC3465703.73. Lee C, Jeong H, Lee H, Hong M, Park SY, Bae H. 2020; Magnolol attenuates cisplatin-induced muscle wasting by M2c macrophage activation. Front Immunol. 11:77. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00077. PMID: 32117241. PMCID: PMC7018987.74. Miki S, Suzuki JI, Takashima M, Ishida M, Kokubo H, Yoshizumi M. 2021; S-1-Propenylcysteine promotes IL-10-induced M2c macrophage polarization through prolonged activation of IL-10R/STAT3 signaling. Sci Rep. 11:22469. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-01866-3. PMID: 34789834. PMCID: PMC8599840.75. Tian L, Yu Q, Liu D, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Lu J, et al. 2022; Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells is enhanced by M2c macrophage polarization. Immunol Invest. 51:301–15. DOI: 10.1080/08820139.2020.1828911. PMID: 34490837.76. Duluc D, Delneste Y, Tan F, Moles MP, Grimaud L, Lenoir J, et al. 2007; Tumor-associated leukemia inhibitory factor and IL-6 skew monocyte differentiation into tumor-associated macrophage-like cells. Blood. 110:4319–30. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072587. PMID: 17848619.77. Wang Q, Ni H, Lan L, Wei X, Xiang R, Wang Y. 2010; Fra-1 protooncogene regulates IL-6 expression in macrophages and promotes the generation of M2d macrophages. Cell Res. 20:701–12. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2010.52. PMID: 20386569.78. Novak ML, Koh TJ. 2013; Macrophage phenotypes during tissue repair. J Leukoc Biol. 93:875–81. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.1012512. PMID: 23505314. PMCID: PMC3656331.79. Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. 2008; Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 13:453–61. DOI: 10.2741/2692. PMID: 17981560.80. Ferrante CJ, Leibovich SJ. 2012; Regulation of macrophage polarization and wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 1:10–6. DOI: 10.1089/wound.2011.0307. PMID: 24527272. PMCID: PMC3623587.81. Atri C, Guerfali FZ, Laouini D. 2018; Role of human macrophage polarization in inflammation during infectious diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 19:1801. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19061801. PMID: 29921749. PMCID: PMC6032107.82. Viola A, Munari F, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Scolaro T, Castegna A. 2019; The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front Immunol. 10:1462. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01462. PMID: 31333642. PMCID: PMC6618143.83. Mosser DM, Edwards JP. 2008; Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:958–69. DOI: 10.1038/nri2448. PMID: 19029990. PMCID: PMC2724991.84. Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Salgame P, Mosser DM. 1998; Reversal of proinflammatory responses by ligating the macrophage Fcgamma receptor type I. J Exp Med. 188:217–22. DOI: 10.1084/jem.188.1.217. PMID: 9653099. PMCID: PMC2525554.85. Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Clynes R, Mosser DM. 1997; Selective suppression of interleukin-12 induction after macrophage receptor ligation. J Exp Med. 185:1977–85. DOI: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1977. PMID: 9166427. PMCID: PMC2196339.86. Lucas M, Zhang X, Prasanna V, Mosser DM. 2005; ERK activation following macrophage FcgammaR ligation leads to chromatin modifications at the IL-10 locus. J Immunol. 175:469–77. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.469. PMID: 15972681.87. Chandrasekaran P, Izadjoo S, Stimely J, Palaniyandi S, Zhu X, Tafuri W, et al. 2019; Regulatory macrophages inhibit alternative macrophage activation and attenuate pathology associated with fibrosis. J Immunol. 203:2130–40. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900270. PMID: 31541024.88. Edwards JP, Zhang X, Frauwirth KA, Mosser DM. 2006; Biochemical and functional characterization of three activated macrophage populations. J Leukoc Biol. 80:1298–307. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.0406249. PMID: 16905575. PMCID: PMC2642590.89. Fleming BD, Chandrasekaran P, Dillon LA, Dalby E, Suresh R, Sarkar A, et al. 2015; The generation of macrophages with anti-inflammatory activity in the absence of STAT6 signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 98:395–407. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.2A1114-560R. PMID: 26048978. PMCID: PMC4541501.90. Gordon S. 2003; Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 3:23–35. DOI: 10.1038/nri978. PMID: 12511873.91. Riquelme P, Haarer J, Kammler A, Walter L, Tomiuk S, Ahrens N, et al. 2018; TIGIT+ iTregs elicited by human regulatory macrophages control T cell immunity. Nat Commun. 9:2858. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05167-8. PMID: 30030423. PMCID: PMC6054648.92. Yeung ST, Ovando LJ, Russo AJ, Rathinam VA, Khanna KM. 2023; CD169+ macrophage intrinsic IL-10 production regulates immune homeostasis during sepsis. Cell Rep. 42:112171. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112171. PMID: 36867536. PMCID: PMC10123955.93. Vos AC, Wildenberg ME, Arijs I, Duijvestein M, Verhaar AP, de Hertogh G, et al. 2012; Regulatory macrophages induced by infliximab are involved in healing in vivo and in vitro. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18:401–8. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21818. PMID: 21936028.94. Ziegler T, Rausch S, Steinfelder S, Klotz C, Hepworth MR, Kühl AA, et al. 2015; A novel regulatory macrophage induced by a helminth molecule instructs IL-10 in CD4+ T cells and protects against mucosal inflammation. J Immunol. 194:1555–64. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401217. PMID: 25589067.95. Nie H, Wang A, He Q, Yang Q, Liu L, Zhang G, et al. 2017; Phenotypic switch in lung interstitial macrophage polarization in an ovalbumin-induced mouse model of asthma. Exp Ther Med. 14:1284–92. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2017.4699. PMID: 28810589. PMCID: PMC5526127.96. Zhang G, Hara H, Yamamoto T, Li Q, Jagdale A, Li Y, et al. 2018; Serum amyloid a as an indicator of impending xenograft failure: experimental studies. Int J Surg. 60:283–90. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.11.027. PMID: 30521954. PMCID: PMC6310230.97. Hamilton TA, Zhao C, Pavicic PG Jr, Datta S. 2014; Myeloid colony-stimulating factors as regulators of macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 5:554. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00554. PMID: 25484881. PMCID: PMC4240161.98. Munn DH, Armstrong E. 1993; Cytokine regulation of human monocyte differentiation in vitro: the tumor-cytotoxic phenotype induced by macrophage colony-stimulating factor is developmentally regulated by gamma-interferon. Cancer Res. 53:2603–13.99. Hutchinson JA, Riquelme P, Geissler EK, Fändrich F. 2011; Human regulatory macrophages. Methods Mol Biol. 677:181–92. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-60761-869-0_13. PMID: 20941611.100. Rückerl D, Hessmann M, Yoshimoto T, Ehlers S, Hölscher C. 2006; Alternatively activated macrophages express the IL-27 receptor alpha chain WSX-1. Immunobiology. 211:427–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.008. PMID: 16920482.101. Desgeorges T, Caratti G, Mounier R, Tuckermann J, Chazaud B. 2019; Glucocorticoids shape macrophage phenotype for tissue repair. Front Immunol. 10:1591. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01591. PMID: 31354730. PMCID: PMC6632423.102. Chen L, Eapen MS, Zosky GR. 2017; Vitamin D both facilitates and attenuates the cellular response to lipopolysaccharide. Sci Rep. 7:45172. DOI: 10.1038/srep45172. PMID: 28345644. PMCID: PMC5366921.103. Pham HL, Hoang TX, Kim JY. 2023; Human regulatory macrophages derived from THP-1 cells using arginylglycylaspartic acid and vitamin D3. Biomedicines. 11:1740. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines11061740. PMID: 37371835. PMCID: PMC10296385.104. Byles V, Covarrubias AJ, Ben-Sahra I, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM, Manning BD, et al. 2013; The TSC-mTOR pathway regulates macrophage polarization. Nat Commun. 4:2834. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3834. PMID: 24280772. PMCID: PMC3876736.105. Pham HL, Yang DH, Chae WR, Jung JH, Hoang TX, Lee NY, et al. 2023; PDMS micropatterns coated with PDA and RGD induce a regulatory macrophage-like phenotype. Micromachines (Basel). 14:673. DOI: 10.3390/mi14030673. PMID: 36985080. PMCID: PMC10052727.106. Riquelme P, Amodio G, Macedo C, Moreau A, Obermajer N, Brochhausen C, et al. 2017; DHRS9 is a stable marker of human regulatory macrophages. Transplantation. 101:2731–8. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001814. PMID: 28594751. PMCID: PMC6319563.107. Du L, Lin L, Li Q, Liu K, Huang Y, Wang X, et al. 2019; IGF-2 preprograms maturing macrophages to acquire oxidative phosphorylation-dependent anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 29:1363–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.006. PMID: 30745181.108. Suzuki H, Hisamatsu T, Chiba S, Mori K, Kitazume MT, Shimamura K, et al. 2016; Glycolytic pathway affects differentiation of human monocytes to regulatory macrophages. Immunol Lett. 176:18–27. DOI: 10.1016/j.imlet.2016.05.009. PMID: 27208804.109. Schmidt A, Zhang XM, Joshi RN, Iqbal S, Wahlund C, Gabrielsson S, et al. 2016; Human macrophages induce CD4(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells via binding and re-release of TGF-β. Immunol Cell Biol. 94:747–62. DOI: 10.1038/icb.2016.34. PMID: 27075967.110. Hörhold F, Eisel D, Oswald M, Kolte A, Röll D, Osen W, et al. 2020; Reprogramming of macrophages employing gene regulatory and metabolic network models. PLoS Comput Biol. 16:e1007657. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007657. PMID: 32097424. PMCID: PMC7059956.111. Raggi F, Pelassa S, Pierobon D, Penco F, Gattorno M, Novelli F, et al. 2017; Regulation of human macrophage M1-M2 polarization balance by hypoxia and the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1. Front Immunol. 8:1097. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01097. PMID: 28936211. PMCID: PMC5594076.112. Goerdt S, Politz O, Schledzewski K, Birk R, Gratchev A, Guillot P, et al. 1999; Alternative versus classical activation of macrophages. Pathobiology. 67:222–6. DOI: 10.1159/000028096. PMID: 10725788.113. Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. 2005; Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 23:344–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. PMID: 16226499.114. Lawrence T, Natoli G. 2011; Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 11:750–61. DOI: 10.1038/nri3088. PMID: 22025054.115. Ishii M, Wen H, Corsa CA, Liu T, Coelho AL, Allen RM, et al. 2009; Epigenetic regulation of the alternatively activated macrophage phenotype. Blood. 114:3244–54. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217620. PMID: 19567879. PMCID: PMC2759649.116. Stout RD, Jiang C, Matta B, Tietzel I, Watkins SK, Suttles J. 2005; Macrophages sequentially change their functional phenotype in response to changes in microenvironmental influences. J Immunol. 175:342–9. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.342. PMID: 15972667.117. Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. 2013; Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 14:986–95. DOI: 10.1038/ni.2705. PMID: 24048120. PMCID: PMC4045180.118. Davies LC, Rosas M, Smith PJ, Fraser DJ, Jones SA, Taylor PR. 2011; A quantifiable proliferative burst of tissue macrophages restores homeostatic macrophage populations after acute inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 41:2155–64. DOI: 10.1002/eji.201141817. PMID: 21710478.119. Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, Jones LH, Finkelman FD, van Rooijen N, et al. 2011; Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 332:1284–8. DOI: 10.1126/science.1204351. PMID: 21566158. PMCID: PMC3128495.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current Status of Solid Organ Xenotransplantation

- Macrophages in xenotransplantation

- Regulatory macrophages as potential cell-based immunotherapy for organ xenotransplantation

- Current Strategies for Successful Islet Xenotransplantation

- Generation and characterization of regulatory macrophages for xenotransplantation