Ewha Med J.

2023 Oct;46(4):e17. 10.12771/emj.2023.e17.

Protective Effects of Statins against Alzheimer Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Fertility and Infertility Research Center, Health Technology Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 2Department of Tissue Engineering, School of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 3Department of Physiology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 4Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran

- 5School of Pharmacy, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- KMID: 2547921

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2023.e17

Abstract

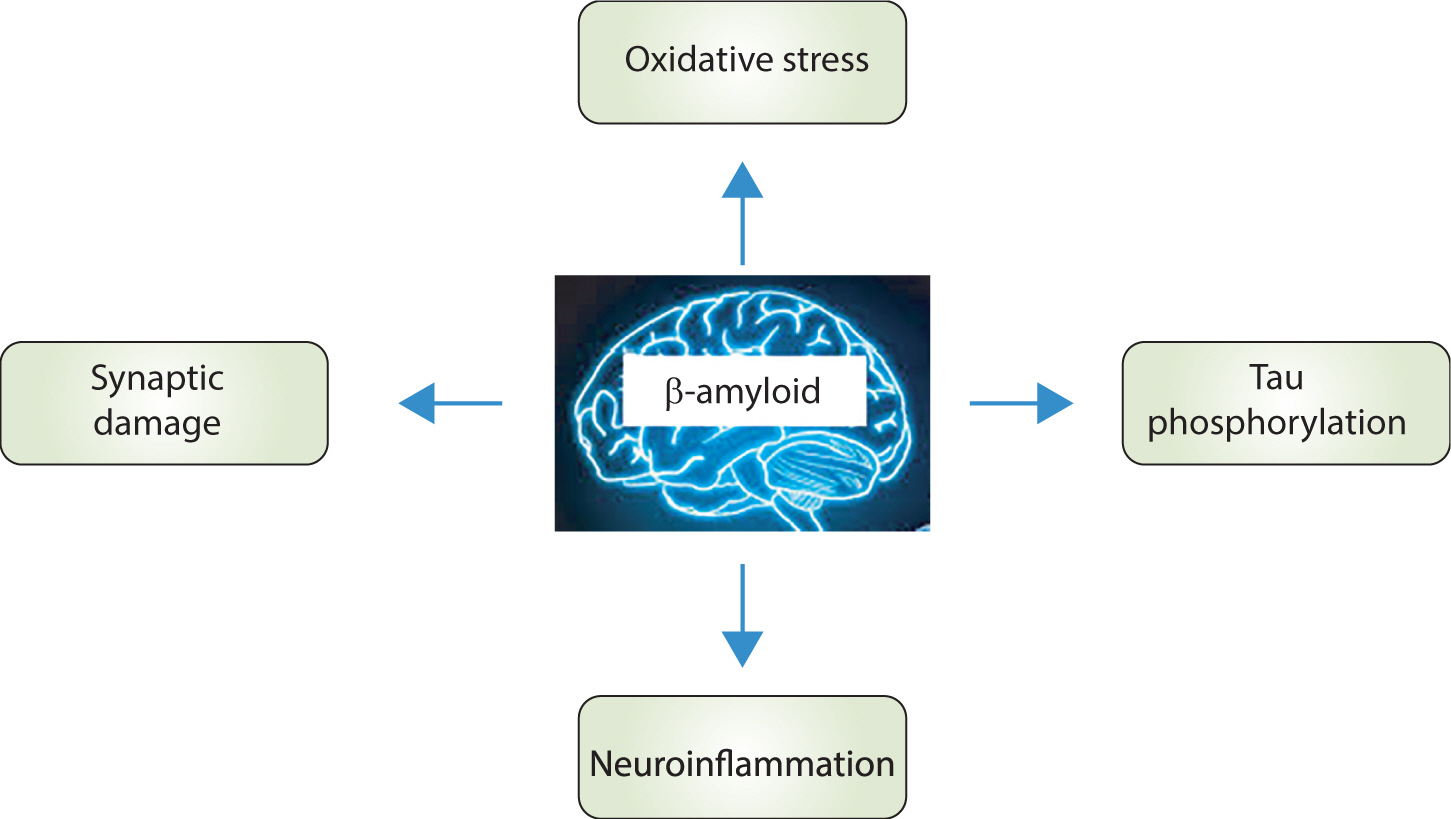

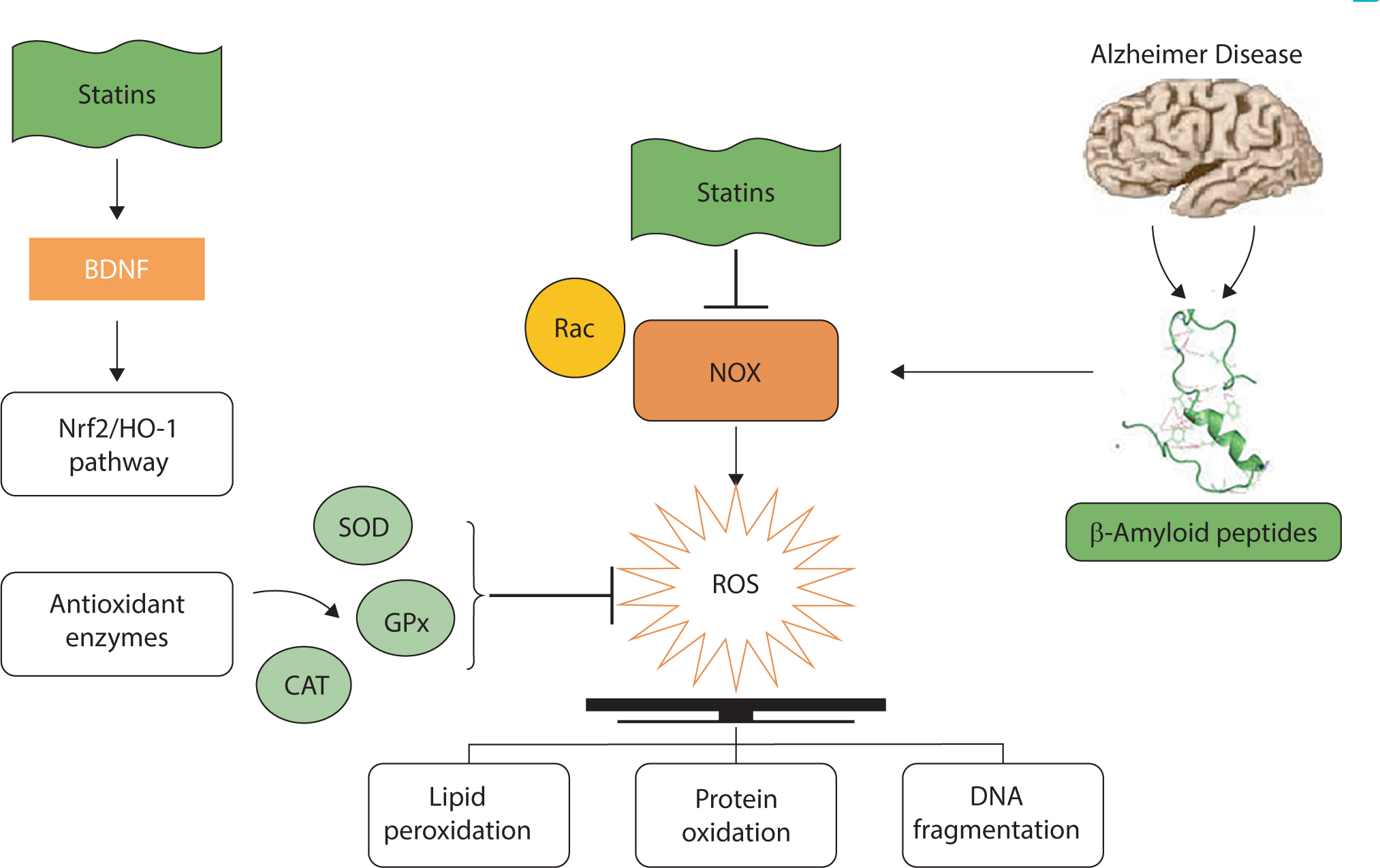

- Alzheimer disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by memory impairment, dementia, and diminished cognitive function. This disease affects more than 20 million people worldwide. Amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are important pathological markers of AD. Multiple studies have indicated a potential association between elevated cholesterol levels and increased risk of AD, suggesting that lowering the cholesterol level could be a viable strategy for AD treatment or prevention. Statins, potent inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis, are widely used in clinical practice to decrease the plasma levels of LDL cholesterol in patients with hyperlipidemia. Statins are known to play a neuroprotective role in limiting Aβ pathology through cholesterol-lowering therapies. In addition to Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the brains of AD patients exhibit signs of oxidative stress, neuroinflammatory responses, and synaptic disruption. Consequently, compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and/or neuroprotective properties could be beneficial components of AD treatment strategies. In addition to lowering LDL cholesterol, statins have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in various forms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects. These properties of statins are potential mechanisms underlying their beneficial effects in treating neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, this review was conducted to provide an overview of the protective effects of statins against AD.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Hollingworth P, Harold D, Jones L, Owen MJ, Williams J. Alzheimer’s disease genetics: current knowledge and future challenges. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011; 26((8)):793–802. DOI: 10.1002/gps.2628. PMID: 20957767.2. Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004; 430((7000)):631–639. DOI: 10.1038/nature02621. PMID: 15295589. PMCID: PMC3091392.3. Kommaddi RP, Das D, Karunakaran S, Nanguneri S, Bapat D, Ray A, et al. Aβ mediates F-actin disassembly in dendritic spines leading to cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2018; 38((5)):1085–1099. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2127-17.2017. PMID: 29246925. PMCID: PMC5792472.4. Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362((4)):329–344. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. PMID: 20107219.5. Bedi O, Dhawan V, Sharma PL, Kumar P. Pleiotropic effects of statins: new therapeutic targets in drug design. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2016; 389((7)):695–712. DOI: 10.1007/s00210-016-1252-4. PMID: 27146293.6. Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990; 343((6257)):425–430. DOI: 10.1038/343425a0. PMID: 1967820.7. Van Aelst L, D’Souza-Schorey C. Rho GTPases and signaling networks. Genes Dev. 1997; 11((18)):2295–2322. DOI: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2295. PMID: 9308960.8. Oryan A, Kamali A, Moshiri A. Potential mechanisms and applications of statins on osteogenesis: current modalities, conflicts and future directions. J Control Release. 2015; 215:12–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.022. PMID: 26226345.9. Li L, Zhang W, Cheng S, Cao D, Parent M. Isoprenoids and related pharmacological interventions: potential application in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2012; 46((1)):64–77. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-012-8253-1. PMID: 22418893. PMCID: PMC4440689.10. Samant NP, Gupta GL. Novel therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease targeting brain cholesterol homeostasis. Eur J Neurosci. 2020; 53((2)):673–686. DOI: 10.1111/ejn.14949. PMID: 32852876.11. Pan ML, Hsu CC, Chen YM, Yu HK, Hu GC. Statin use and the risk of dementia in patients with stroke: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018; 27((11)):3001–3007. DOI: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.06.036. PMID: 30087076.12. Sinyavskaya L, Gauthier S, Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S, Brassard P. Comparative effect of statins on the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018; 90((3)):e179–e187. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004818. PMID: 29247073.13. Sodero AO, Barrantes FJ. Pleiotropic effects of statins on brain cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2020; 1862((9)):183340. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183340. PMID: 32387399.14. Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002; 297((5580)):353–356. DOI: 10.1126/science.1072994. PMID: 12130773.15. Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and ’wingmen’. Nat Neurosci. 2015; 18((6)):800–806. DOI: 10.1038/nn.4018. PMID: 26007213. PMCID: PMC4445458.16. Alvarez A, Toro R, Cáceres A, Maccioni RB. Inhibition of tau phosphorylating protein kinase cdk5 prevents β-amyloid-induced neuronal death. FEBS Lett. 1999; 459((3)):421–426. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01279-X. PMID: 10526177.17. Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010; 142((3)):387–397. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. PMID: 20655099.18. Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, Nagata K, Saito T, De Strooper B, et al. APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J. 2017; 36((17)):2473–2487. DOI: 10.15252/embj.201797397. PMID: 28768718. PMCID: PMC5579350.19. Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011; 1((1)):a006189. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. PMID: 22229116. PMCID: PMC3234452.20. Solomon A, Kåreholt I, Ngandu T, Winblad B, Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J, et al. Serum cholesterol changes after midlife and late-life cognition: twenty-one-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2007; 68((10)):751–756. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256368.57375.b7. PMID: 17339582.21. Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005; 64((2)):277–281. DOI: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2. PMID: 15668425.22. Luchesi BM, de Souza Melo BR, Balderrama P, Gratão ACM, Chagas MHN, Pavarini SCI, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for dementia in middle- and older-aged people registered in Primary Health Care. Dement Neuropsychol. 2021; 15((2)):239–247. DOI: 10.1590/1980-57642021dn15-020012. PMID: 34345366. PMCID: PMC8283878.23. Lazar AN, Bich C, Panchal M, Desbenoit N, Petit VW, Touboul D, et al. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) imaging reveals cholesterol overload in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2013; 125((1)):133–144. DOI: 10.1007/s00401-012-1041-1. PMID: 22956244.24. Sparks DL, Kuo YM, Roher A, Martin T, Lukas RJ. Alterations of Alzheimer’s disease in the cholesterol-fed rabbit, including vascular inflammation: preliminary observations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000; 903((1)):335–344. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06384.x. PMID: 10818523.25. O’Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011; 34:185–204. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. PMID: 21456963. PMCID: PMC3174086.26. Jick H, Zornberg GL, Jick SS, Seshadri S, Drachman DA. Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet. 2000; 356((9242)):1627–1631. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03155-X. PMID: 11089820.27. Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science. 2001; 292((5519)):1160–1164. DOI: 10.1126/science.1059344. PMID: 11349148.28. Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P, Celesia GG, Siegel G. Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol. 2000; 57((10)):1439–1443. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1439. PMID: 11030795.29. Jeong A, Suazo KF, Wood WG, Distefano MD, Li L. Isoprenoids and protein prenylation: implications in the pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention of Alzheimer’s disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2018; 53((3)):279–310. DOI: 10.1080/10409238.2018.1458070. PMID: 29718780. PMCID: PMC6101676.30. Ostrowski SM, Wilkinson BL, Golde TE, Landreth G. Statins reduce amyloid-β production through inhibition of protein isoprenylation. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282((37)):26832–26844. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M702640200. PMID: 17646164.31. Chassaing S, Collin F, Dorlet P, Gout J, Hureau C, Faller P. Copper and heme-mediated Abeta toxicity: redox chemistry, Abeta oxidations and anti-ROS compounds. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012; 12((22)):2573–2595. DOI: 10.2174/1568026611212220011. PMID: 23339309.32. Kamsler A, Segal M. Hydrogen peroxide as a diffusible signal molecule in synaptic plasticity. Mol Neurobiol. 2004; 29((2)):167–178. DOI: 10.1385/MN:29:2:167. PMID: 15126684.33. Butterfield DA, Bader Lange ML, Sultana R. Involvements of the lipid peroxidation product, HNE, in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2010; 1801((8)):924–929. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.02.005. PMID: 20176130. PMCID: PMC2886168.34. Pillot T, Drouet B, Queillé S, Labeur C, Vandekerckhove J, Rosseneu M, et al. The nonfibrillar amyloid β-peptide induces apoptotic neuronal cell death: involvement of its C-terminal fusogenic domain. J Neurochem. 1999; 73((4)):1626–1634. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731626.x. PMID: 10501209.35. Girona J, La AE, Solà R, Plana N, Masana L. Simvastatin decreases aldehyde production derived from lipoprotein oxidation. Am J Cardiol. 1999; 83((6)):846–851. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)01071-6. PMID: 10190397.36. Franzoni F, Quinones-Galvan A, Regoli F, Ferrannini E, Galetta F. A comparative study of the in vitro antioxidant activity of statins. Int J Cardiol. 2003; 90((2-3)):317–321. DOI: 10.1016/S0167-5273(02)00577-6. PMID: 12957768.37. Davignona J, Jacob R, Mason RP. The antioxidant effects of statins. Coron Artery Dis. 2004; 15((5)):251–258. DOI: 10.1097/01.mca.0000131573.31966.34. PMID: 15238821.38. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007; 87((1)):245–313. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. PMID: 17237347.39. Milton RH, Abeti R, Averaimo S, DeBiasi S, Vitellaro L, Jiang L, et al. CLIC1 function is required for β-amyloid-induced generation of reactive oxygen species by microglia. J Neurosci. 2008; 28((45)):11488–11499. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2431-08.2008. PMID: 18987185. PMCID: PMC6671295.40. Tong H, Zhang X, Meng X, Lu L, Mai D, Qu S. Simvastatin inhibits activation of NADPH oxidase/p38 MAPK pathway and enhances expression of antioxidant protein in Parkinson disease models. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018; 11:165. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00165. PMID: 29872377. PMCID: PMC5972184.41. Kwok JMF, Ma CC, Ma S. Recent development in the effects of statins on cardiovascular disease through Rac1 and NADPH oxidase. Vascul Pharmacol. 2013; 58((1-2)):21–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.10.003. PMID: 23085091.42. Pérez-Guerrero C, de Sotomayor MA, Jimenez L, Herrera MD, Marhuenda E. Effects of simvuastatin on endothelial function after chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthase by L-NAME. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003; 42((2)):204–210. DOI: 10.1097/00005344-200308000-00008. PMID: 12883323.43. Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016; 73((17)):3221–3247. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-016-2223-0. PMID: 27100828. PMCID: PMC4967105.44. Yagishita Y, Uruno A, Fukutomi T, Saito R, Saigusa D, Pi J, et al. Nrf2 improves leptin and insulin resistance provoked by hypothalamic oxidative stress. Cell Rep. 2017; 18((8)):2030–2044. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.064. PMID: 28228267.45. Chartoumpekis D, Ziros PG, Psyrogiannis A, Kyriazopoulou V, Papavassiliou AG, Habeos IG. Simvastatin lowers reactive oxygen species level by Nrf2 activation via PI3K/Akt pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010; 396((2)):463–466. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.117. PMID: 20417615.46. Habeos IG, Ziros PG, Chartoumpekis D, Psyrogiannis A, Kyriazopoulou V, Papavassiliou AG. Simvastatin activates Keap1/Nrf2 signaling in rat liver. J Mol Med. 2008; 86((11)):1279–1285. DOI: 10.1007/s00109-008-0393-4. PMID: 18787804.47. Yamamoto A, Hoshi K, Ichihara K. Fluvastatin, an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, scavenges free radicals and inhibits lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998; 361((1)):143–149. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00692-X. PMID: 9851551.48. Jeon SM, Bok SH, Jang MK, Lee MK, Nam KT, Park YB, et al. Antioxidative activity of naringin and lovastatin in high cholesterol-fed rabbits. Life Sci. 2001; 69((24)):2855–2866. DOI: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01363-7. PMID: 11720089.49. Schain M, Kreisl WC. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017; 17((3)):25. DOI: 10.1007/s11910-017-0733-2. PMID: 28283959.50. Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, et al. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989; 86((19)):7611–7615. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7611. PMID: 2529544. PMCID: PMC298116.51. Kinney JW, Bemiller SM, Murtishaw AS, Leisgang AM, Salazar AM, Lamb BT. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018; 4:575–590. DOI: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.014. PMID: 30406177. PMCID: PMC6214864.52. Meraz-Ríos MA, Toral-Rios D, Franco-Bocanegra D, Villeda-Hernández J, Campos-Peña V. Inflammatory process in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013; 7:59. DOI: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00059. PMID: 23964211. PMCID: PMC3741576.53. Nisbet RM, Polanco JC, Ittner LM, Götz J. Tau aggregation and its interplay with amyloid-β. Acta Neuropathol. 2015; 129((2)):207–220. DOI: 10.1007/s00401-014-1371-2. PMID: 25492702. PMCID: PMC4305093.54. Ostrowski SM, Wilkinson BL, Golde TE, Landreth G. Statins reduce amyloid-β production through inhibition of protein isoprenylation. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282((37)):26832–26844. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M702640200. PMID: 17646164.55. Clarke RM, O’Connell F, Lyons A, Lynch MA. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, attenuates the effects of acute administration of amyloid-β1–42 in the rat hippocampus in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2007; 52((1)):136–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.031. PMID: 16920163.56. Thompson KK, Tsirka SE. The diverse roles of Microglia in the neurodegenerative aspects of Central Nervous System (CNS) autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 18((3)):504. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18030504. PMID: 28245617. PMCID: PMC5372520.57. Yamamoto Y, Gaynor R. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Investig. 2001; 107((2)):135–142. DOI: 10.1172/JCI11914. PMID: 11160126. PMCID: PMC199180.58. Link A, Ayadhi T, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Rapid immunomodulation by rosuvastatin in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27((24)):2945–2955. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl277. PMID: 17012299.59. Lindberg C, Crisby M, Winblad B, Schultzberg M. Effects of statins on microglia. J Neurosci Res. 2005; 82((1)):10–19. DOI: 10.1002/jnr.20615. PMID: 16118799.60. Inoue I, Goto S, Mizotani K, Awata T, Mastunaga T, Kawai S, et al. Lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has an anti-inflammatory effect: reduction of MRNA levels for interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, cyclooxygenase-2, and p22phox by regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARalpha) in primary endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2000; 67((8)):863–876. DOI: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00680-9. PMID: 10946846.61. Jones SV, Kounatidis I. Nuclear factor-kappa B and Alzheimer disease, unifying genetic and environmental risk factors from cell to humans. Front Immunol. 2017; 8:1805. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01805. PMID: 29312321. PMCID: PMC5732234.62. Hilgendorff A, Muth H, Parviz B, Staubitz A, Haberbosch W, Tillmanns H, et al. Statins differ in their ability to block NF-kappaB activation in human blood monocytes. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 41((9)):397–401. DOI: 10.5414/CPP41397. PMID: 14518599.63. Hernández-Presa MA, Martı́n-Ventura JL, Ortego M, Gómez-Hernández A, Tuñón J, Hernández-Vargas P, et al. Atorvastatin reduces the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis and in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2002; 160((1)):49–58. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00547-0. PMID: 11755922.64. Gasparini C, Feldmann M. NF-κB as a target for modulating inflammatory responses. Curr Pharm Des. 2012; 18((35)):5735–5745. DOI: 10.2174/138161212803530763. PMID: 22726116.65. Ortego M, Bustos C, Hernández-Presa J, Tuñón J, Díaz C, Hernández G, et al. Atorvastatin reduces NF-kappaB activation and chemokine expression in vascular smooth muscle cells and mononuclear cells. Atherosclerosis. 1999; 147((2)):253–261. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00193-8. PMID: 10559511.66. Yamamoto K, Arakawa T, Ueda N, Yamamoto S. Transcriptional roles of nuclear factor κB and nuclear factor-interleukin-6 in the tumor necrosis factor α-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270((52)):31315–31320. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31315. PMID: 8537402.67. Ramalho TC, Rocha MVJ, da Cunha EFF, Freitas MP. The search for new COX-2 inhibitors: a review of 2002–2008 patents. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009; 19((9)):1193–1228. DOI: 10.1517/13543770903059125. PMID: 19563267.68. Bliss TVP, Lomø T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973; 232((2)):331–356. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. PMID: 4727084. PMCID: PMC1350458.69. Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004; 44((1)):5–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. PMID: 15450156.70. Stéphan A, Laroche S, Davis S. Generation of aggregated β-amyloid in the rat hippocampus impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity and causes memory deficits. J Neurosci. 2001; 21((15)):5703–5714. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05703.2001. PMID: 11466442. PMCID: PMC6762634.71. Chen QS, Wei WZ, Shimahara T, Xie CW. Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide inhibits the late phase of long-term potentiation through calcineurin-dependent mechanisms in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002; 77((3)):354–371. DOI: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4034. PMID: 11991763.72. Benarroch EE. Glutamatergic synaptic plasticity and dysfunction in Alzheimer disease: emerging mechanisms. Neurology. 2018; 91((3)):125–132. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005807. PMID: 29898976.73. Raymond CR, Ireland DR, Abraham WC. NMDA receptor regulation by amyloid-β does not account for its inhibition of LTP in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003; 968((2)):263–272. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02269-8. PMID: 12663096.74. Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of β-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95((11)):6460–6464. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. PMID: 9600988. PMCID: PMC27798.75. Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, Stroick M, Lütjohann D, Keller P, et al. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides Aβ42 and Aβ40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98((10)):5856–5861. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. PMID: 11296263. PMCID: PMC33303.76. Tamboli IY, Barth E, Christian L, Siepmann M, Kumar S, Singh S, et al. Statins promote the degradation of extracellular amyloid β-peptide by microglia via stimulation of exosome-associated insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) secretion. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285((48)):37405–37414. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149468. PMID: 20876579. PMCID: PMC2988346.77. Kurata T, Miyazaki K, Kozuki M, Panin VL, Morimoto N, Ohta Y, et al. Atorvastatin and pitavastatin improve cognitive function and reduce senile plaque and phosphorylated tau in aged APP mice. Brain Res. 2011; 1371:161–170. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.067. PMID: 21112317.78. Zhang YY, Fan YC, Wang M, Wang D, Li XH. Atorvastatin attenuates the production of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the hippocampus of an amyloid β1-42-induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2013; 8:103–110. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S40405. PMID: 23386786. PMCID: PMC3563315.79. Tong XK, Lecrux C, Hamel E. Age-dependent rescue by simvastatin of Alzheimer’s disease cerebrovascular and memory deficits. J Neurosci. 2012; 32((14)):4705–4715. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0169-12.2012. PMID: 22492027. PMCID: PMC6620905.80. Mans RA, McMahon LL, Li L. Simvastatin-mediated enhancement of long-term potentiation is driven by farnesyl-pyrophosphate depletion and inhibition of farnesylation. Neuroscience. 2012; 202:1–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.007. PMID: 22192838. PMCID: PMC3626073.81. Roy A, Jana M, Kundu M, Corbett GT, Rangaswamy SB, Mishra RK, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors bind to PPARα to upregulate neurotrophin expression in the brain and improve memory in mice. Cell Metab. 2015; 22((2)):253–265. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.022. PMID: 26118928. PMCID: PMC4526399.82. Salcedo-Tello P, Ortiz-Matamoros A, Arias C. GSK3 function in the brain during development, neuronal plasticity, and neurodegeneration. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011; 2011:189728. DOI: 10.4061/2011/189728. PMID: 21660241. PMCID: PMC3109514.83. Muyllaert D, Kremer A, Jaworski T, Borghgraef P, Devijver H, Croes S, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β, or a link between amyloid and tau pathology? Genes Brain Behav. 2008; 7((1)):57–66. DOI: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00376.x. PMID: 18184370.84. Kim JW, Lee JE, Kim MJ, Cho EG, Cho SG, Choi EJ. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β is a natural activator of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1). J Biol Chem. 2003; 278((16)):13995–14001. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M300253200. PMID: 12584189.85. Salins P, Shawesh S, He Y, Dibrov A, Kashour T, Arthur G, et al. Lovastatin protects human neurons against Aβ-induced toxicity and causes activation of β-catenin–TCF/LEF signaling. Neurosci Lett. 2007; 412((3)):211–216. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.045. PMID: 17234346.86. Burghaus L, Schütz U, Krempel U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Wevers A, et al. Quantitative assessment of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer patients. Mol Brain Res. 2000; 76((2)):385–388. DOI: 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00031-0. PMID: 10762715.87. Ladner CJ, Lee JM. Pharmacological drug treatment of Alzheimer disease: the cholinergic hypothesis revisited. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998; 57((8)):719–731. DOI: 10.1097/00005072-199808000-00001. PMID: 9720487.88. Fisher A. M1 muscarinic agonists target major hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease-an update. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007; 4((5)):577–580. DOI: 10.2174/156720507783018163. PMID: 18220527.89. Zhao Z, Zhao S, Xu N, Yu C, Guan S, Liu X, et al. Lovastatin improves neurological outcome after nucleus basalis magnocellularis lesion in rats. Neuroscience. 2010; 167((3)):954–963. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.054. PMID: 20219644.90. Cibičková L, Palička V, Cibiček N, Čermáková E, Mičuda S, Bartošová L, et al. Differential effects of statins and alendronate on cholinesterases in serum and brain of rats. Physiol Res. 2007; 56((6)):765–770. DOI: 10.33549/physiolres.931121. PMID: 17087598.91. Zhou J, Freeman TA, Ahmad F, Shang X, Mangano E, Gao E, et al. GSK-3α is a central regulator of age-related pathologies in mice. J Clin Investig. 2013; 123((4)):1821–1832. DOI: 10.1172/JCI64398. PMID: 23549082. PMCID: PMC3613907.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Memorials of Alois Alzheimer (June 14, 1864~December 19, 1915) and Historical Background of Alzheimer's Disease

- Significance of Non-Alzheimer Dementia

- Alzheimer's Disease: Clinical Trials and Future Perspectives

- Adverse effects of statin therapy and their treatment

- Chemoprevention of Gastric Cancer: Statins