J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Jul;38(28):e217. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e217.

Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Mortality in Critical COVID-19 Patients Aged 50 Years or Younger During Omicron Wave in Korea: Comparison With Patients Older Than 50 Years of Age

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Infectious Diseases, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- 4Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea

- 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Ansan, Korea

- 6Department of Infectious Diseases, Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 7Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Changwon Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea

- 9Division of Infectious Diseases, Chungnam National University Sejong Hospital, Sejong, Korea

- 10Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Pusan National University, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2544476

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e217

Abstract

- Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused the death of thousands of patients worldwide. Although age is known to be a risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients, critical illness or death is occurring even in the younger age group as the epidemic spreads. In early 2022, omicron became the dominant variant of the COVID-19 virus in South Korea, and the epidemic proceeded on a large scale. Accordingly, this study aimed to determine whether young adults (aged ≤ 50 years) with critical COVID-19 infection during the omicron period had different characteristics from older patients and to determine the risk factors for mortality in this specific age group.

Methods

We evaluated 213 critical adult patients (high flow nasal cannula or higher respiratory support) hospitalized for polymerase chain reaction-confirmed COVID-19 in nine hospitals in South Korea between February 1, 2022 and April 30, 2022. Demographic characteristics, including body mass index (BMI) and vaccination status; underlying diseases; clinical features and laboratory findings; clinical course; treatment received; and outcomes were collected from electronic medical records (EMRs) and analyzed according to age and mortality.

Results

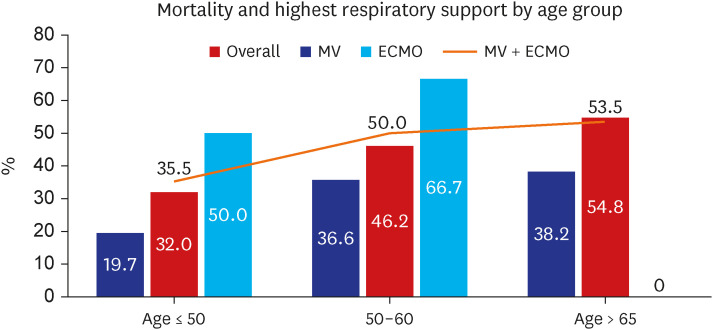

Overall, 71 critically ill patients aged ≤ 50 years were enrolled, and 142 critically ill patients aged over 50 years were selected through 1:2 matching based on the date of diagnosis. The most frequent underlying diseases among those aged ≤ 50 years were diabetes and hypertension, and all 14 patients who died had either a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 or an underlying disease. The total case fatality rate among severe patients (S-CFR) was 31.0%, and the S-CFR differed according to age and was higher than that during the delta period. The S-CFR was 19.7% for those aged ≤ 50 years, 36.6% for those aged > 50 years, and 38.1% for those aged ≥ 65 years. In multivariate analysis, age (odds ratio [OR], 1.084; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.043–1.127), initial low-density lipoprotein > 600 IU/L (OR, 4.782; 95% CI, 1.584–14.434), initial C-reactive protein > 8 mg/dL (OR, 2.940; 95% CI, 1.042–8.293), highest aspartate aminotransferase > 200 IU/L (OR, 12.931; 95% CI, 1.691–98.908), and mechanical ventilation implementation (OR, 3.671; 95% CI, 1.294–10.420) were significant independent predictors of mortality in critical COVID-19 patients during the omicron wave. A similar pattern was shown when analyzing the data by age group, but most had no statistical significance owing to the small number of deaths in the young critical group. Although the vaccination completion rate of all the patients (31.0%) was higher than that in the delta wave period (13.6%), it was still lower than that of the general population. Further, only 15 (21.1%) critically ill patients aged ≤ 50 years were fully vaccinated. Overall, the severity of hospitalized critical patients was significantly higher than that in the delta period, indicating that it was difficult to find common risk factors in the two periods only with a simple comparison.

Conclusion

Overall, the S-CFR of critically ill COVID-19 patients in the omicron period was higher than that in the delta period, especially in those aged ≤ 50 years. All of the patients who died had an underlying disease or obesity. In the same population, the vaccination rate was very low compared to that in the delta wave, indicating that non-vaccination significantly affected the progression to critical illness. Notably, there was a lack of prescription for Paxlovid for these patients although they satisfied the prescription criteria. Early diagnosis and active initial treatment was necessary, along with the proven methods of vaccination and personal hygiene. Further studies are needed to determine how each variant affects critically ill patients.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Comparative Effectiveness of COVID-19 Bivalent Versus Monovalent mRNA Vaccines in the Early Stage of Bivalent Vaccination in Korea: October 2022 to January 2023

Ryu Kyung Kim, Young June Choe, Eun Jung Jang, Chungman Chae, Ji Hae Hwang, Kil Hun Lee, Ji Ae Shim, Geun-Yong Kwon, Jae Young Lee, Young-Joon Park, Sang Won Lee, Donghyok Kwon

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(46):e396. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e396.

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19 - 24 August 2022. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2022.2. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Variants of COVID-19. Updated 2021. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://ncv.kdca.go.kr/hcp/page.do?mid=060102 .3. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Analysis of the COVID-19 Outbreak During the Category 1 Statutory Infectious Disease Designation Period. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2022.4. Kim MK, Lee B, Choi YY, Um J, Lee KS, Sung HK, et al. Clinical characteristics of 40 patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(3):e31. PMID: 35040299.5. Bhattacharyya RP, Hanage WP. Challenges in inferring intrinsic severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(7):e14. PMID: 35108465.6. Ribeiro Xavier C, Sachetto Oliveira R, da Fonseca Vieira V, Lobosco M, Weber Dos Santos R. Characterisation of Omicron Variant during COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact of Vaccination, Transmission Rate, Mortality, and Reinfection in South Africa, Germany, and Brazil. BioTech (Basel). 2022; 11(2):12. PMID: 35822785.7. Bouzid D, Visseaux B, Kassasseya C, Daoud A, Fémy F, Hermand C, et al. Comparison of patients infected with delta versus omicron COVID-19 variants presenting to Paris emergency departments : a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022; 175(6):831–837. PMID: 35286147.8. Shim E, Choi W, Kwon D, Kim T, Song Y. Transmission potential of the omicron variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in South Korea, 25 November 2021-8 January 2022. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022; 9(7):ofac248. PMID: 35855956.9. Lee JJ, Choe YJ, Jeong H, Kim M, Kim S, Yoo H, et al. Importation and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of concern in Korea, November 2021. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(50):e346. PMID: 34962117.10. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020; 180(7):934–943. PMID: 32167524.11. Jang JG, Hur J, Choi EY, Hong KS, Lee W, Ahn JH. Prognostic factors for severe coronavirus disease 2019 in Daegu, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(23):e209. PMID: 32537954.12. Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52(2):154–164. PMID: 32537961.13. Heald-Sargent T, Muller WJ, Zheng X, Rippe J, Patel AB, Kociolek LK. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Pediatr. 2020; 174(9):902–903. PMID: 32745201.14. Murillo-Zamora E, Aguilar-Sollano F, Delgado-Enciso I, Hernandez-Suarez CM. Predictors of laboratory-positive COVID-19 in children and teenagers. Public Health. 2020; 189:153–157. PMID: 33246302.15. Steinberg E, Wright E, Kushner B. In young adults with COVID-19, obesity is associated with adverse outcomes. West J Emerg Med. 2020; 21(4):752–755. PMID: 32726235.16. Lu Y, Huang Z, Wang M, Tang K, Wang S, Gao P, et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality in young adults with severe COVID-19: a retrospective observational study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2021; 20(1):3. PMID: 33407543.17. Forchette L, Sebastian W, Liu T. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 virology, vaccines, variants, and therapeutics. Curr Med Sci. 2021; 41(6):1037–1051. PMID: 34241776.18. Smith DJ, Hakim AJ, Leung GM, Xu W, Schluter WW, Novak RT, et al. COVID-19 mortality and vaccine coverage - Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, January 6, 2022-March 21, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71(15):545–548. PMID: 35421076.19. Martins-Filho PR, de Souza Araújo AA, Quintans-Júnior LJ, Soares BD, Barboza WS, Cavalcante TF, et al. Dynamics of hospitalizations and in-hospital deaths from COVID-19 in northeast Brazil: a retrospective analysis based on the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccination coverage. Epidemiol Health. 2022; 44:e2022036. PMID: 35413166.20. Singanayagam A, Hakki S, Dunning J, Madon KJ, Crone MA, Koycheva A, et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022; 22(2):183–195. PMID: 34756186.21. Shi HJ, Nham E, Kim B, Joo EJ, Cheong HS, Hong SH, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in critical coronavirus disease 2019 patients 50 years of age or younger during the delta wave: comparison with patients > 50 years in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(22):e175. PMID: 35668685.22. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. COVID-19 domestic outbreaks. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/boardApi.es?mid=a20507050000&bid=0080&api_code=20220214 .23. Liu Z, Liu J, Ye L, Yu K, Luo Z, Liang C, et al. Predictors of mortality for hospitalized young adults aged less than 60 years old with severe COVID-19: a retrospective study. J Thorac Dis. 2021; 13(6):3628–3642. PMID: 34277055.24. Lee JY, Kim HA, Huh K, Hyun M, Rhee JY, Jang S, et al. Risk factors for mortality and respiratory support in elderly patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(23):e223. PMID: 32537957.25. Capuzzo M, Amaral AC, Liu VX. Assess COVID-19 prognosis … but be aware of your instrument’s accuracy! Intensive Care Med. 2021; 47(12):1472–1474. PMID: 34608529.26. He F, Page JH, Weinberg KR, Mishra A. The development and validation of simplified machine learning algorithms to predict prognosis of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: multicenter, retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. 2022; 24(1):e31549. PMID: 34951865.27. Jeon HW. [COVID-19] Paxlovid was introduced in Korea about two month ago... but still perscribed only 47000 patients. Aju Business Daily;2022. 03. 16.28. Drożdżal S, Rosik J, Lechowicz K, Machaj F, Szostak B, Przybyciński J, et al. An update on drugs with therapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2021; 59:100794. PMID: 34991982.29. Wen W, Chen C, Tang J, Wang C, Zhou M, Cheng Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2022; 54(1):516–523. PMID: 35118917.30. Lee H, Choi S, Park JY, Jo DS, Choi UY, Lee H, et al. Analysis of critical COVID-19 cases among children in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(1):e13. PMID: 34981683.31. Bienvenu LA, Noonan J, Wang X, Peter K. Higher mortality of COVID-19 in males: sex differences in immune response and cardiovascular comorbidities. Cardiovasc Res. 2020; 116(14):2197–2206. PMID: 33063089.32. Lim S, Shin SM, Nam GE, Jung CH, Koo BK. Proper management of people with obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2020; 29(2):84–98. PMID: 32544885.33. Jung E. Four out of 10 people in the country are obese... COVID-19 obesity rate ‘Biggest Ever’. Korean Financial;2022. 03. 15.34. Ward IL, Bermingham C, Ayoubkhani D, Gethings OJ, Pouwels KB, Yates T, et al. Risk of covid-19 related deaths for SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) compared with delta (B.1.617.2): retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022; 378:e070695. PMID: 35918098.35. Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, Webster HH, Flaxman S, Andrews N, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022; 399(10332):1303–1312. PMID: 35305296.36. Lauring AS, Tenforde MW, Chappell JD, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, McNeal T, et al. Clinical severity of, and effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against, covid-19 from omicron, delta, and alpha SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2022; 376:e069761. PMID: 35264324.37. Chen X, Yan X, Sun K, Zheng N, Sun R, Zhou J, et al. Estimation of disease burden and clinical severity of COVID-19 caused by omicron BA.2 in Shanghai, February-June 2022. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022; 11(1):2800–2807. PMID: 36205530.38. Aleem A, Akbar Samad AB, Vaqar S. Emerging Variants of SARS-CoV-2 And Novel Therapeutics Against Coronavirus (COVID-19). Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls;2023.39. Ahmad Malik J, Ahmed S, Shinde M, Almermesh MH, Alghamdi S, Hussain A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on comorbidities: a review of recent updates for combating it. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022; 29(5):3586–3599. PMID: 35165505.40. Anjan S, Khatri A, Viotti JB, Cheung T, Garcia LA, Simkins J, et al. Is the Omicron variant truly less virulent in solid organ transplant recipients? Transpl Infect Dis. 2022; 24(6):e13923. PMID: 35915957.41. Pinato DJ, Aguilar-Company J, Ferrante D, Hanbury G, Bower M, Salazar R, et al. Outcomes of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant outbreak among vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with cancer in Europe: results from the retrospective, multicentre, OnCovid registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2022; 23(7):865–875. PMID: 35660139.42. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Domestic COVID-19 Variant Virus Detection Rate. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2022.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of the Clinical and Laboratory Features of COVID-19 in Children During All Waves of the Epidemic: A Single Center Retrospective Study

- The Impact of Omicron Wave on Pediatric Febrile Seizure

- Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Mortality in Critical Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients 50 Years of Age or Younger During the Delta Wave: Comparison With Patients > 50 Years in Korea

- Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors in Severely Injured Elderly Trauma Presenting to Emergency Department

- Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus in Patients Younger than 50 Years Versus 50 Years and Older