Korean J Health Promot.

2023 Mar;23(1):18-27. 10.15384/kjhp.2023.23.1.18.

The Difference between Serum Vitamin D Level and Depressive Symptoms in Korean Adult Women before and after Menopause: The 5th (2010–2012) Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 2Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Public Health and Medical Service, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2541206

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15384/kjhp.2023.23.1.18

Abstract

- Background

The relationship between serum vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms has not been consistent in previous studies in Korean women. Menopause is known to be related to depression and vitamin D.

Methods

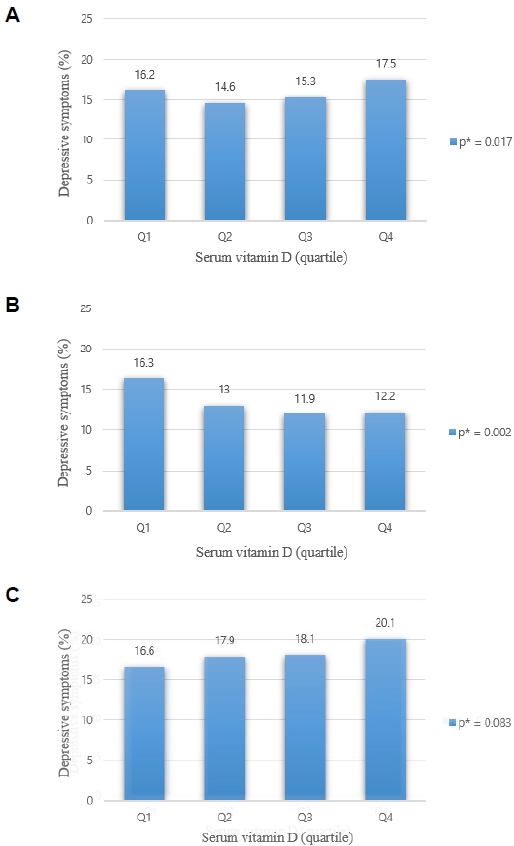

This study included 11,573 women from the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Serum vitamin D levels were divided into four groups according to quartiles, and depressive symptoms were collected into two groups. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted in each group of women before and after menopause.

Results

Compared with the highest vitamin D group, the lowest vitamin D group did not show significant differences in all females (odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-1.22). In premenopausal women, compared to the first quartile, ORs were presented in the second quartile (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-1.07), third quartile (OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.49-1.00) and fourth quartile (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43-0.92) respectively, and they were statistically significant (P=0.016). In postmenopausal women, compared to the first quartile, ORs were presented in the second quartile (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.78-1.44), third quartile (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.87-1.61), and fourth quartile (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.98-1.66) respectively; however, they were not statistically significant (P=0.057).

Conclusions

Depression symptoms increased with a decrease in serum vitamin D in premenopausal women, but the opposite trend was observed in postmenopausal women. In future studies, if the relationship between blood vitamin D and depression is studied, the menopausal status of women can be used as an important criterion.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lopez AD. The evolution of the Global Burden of Disease framework for disease, injury and risk factor quantification: developing the evidence base for national, regional and global public health action. Global Health. 2005; 1(1):5.

Article2. Caradeux J, Martinez-Portilla RJ, Basuki TR, Kiserud T, Figueras F. Risk of fetal death in growth-restricted fetuses with umbilical and/or ductus venosus absent or reversed end-diastolic velocities before 34 weeks of gestation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 218(2S):S774–82.e21.3. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(3):266–81.

Article4. Lee HH. A role of vitamin D in postmenopausal women. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2008; 14(2):109–14.5. May HT, Bair TL, Lappé DL, Anderson JL, Horne BD, Carlquist JF, et al. Association of vitamin D levels with incident depression among a general cardiovascular population. Am Heart J. 2010; 159(6):1037–43.

Article6. Milaneschi Y, Hoogendijk W, Lips P, Heijboer AC, Schoevers R, van Hemert AM, et al. The association between low vitamin D and depressive disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2014; 19(4):444–51.

Article7. Kalueff AV, Tuohimaa P. Neurosteroid hormone vitamin D and its utility in clinical nutrition. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007; 10(1):12–9.

Article8. Shah J, Gurbani S. Association of vitamin D deficiency and mood disorders: a systematic review [Internet]. London: IntechOpen;2019. [cited Jun 30, 2022]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/70606.

Article9. Baek JH, Yang HH, Lee MR, Kang DW, Jeon YJ, Park SG, et al. The association of vitamin D with depressive symptoms in Korean adolescents: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009~ 2011. Korean J Fam Pract. 2015; 5(3):654–8.10. Sang JH, Sung HR, Cho HC, Park KC, Kim MJ, Park KS, et al. The relationship between serum vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in Korean female adults. Korean J Fam Pract. 2015; 5(3):801–5.11. Spinelli MG. Depression and hormone therapy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 47(2):428–36.

Article12. Caruso S, Rapisarda AM, Cianci S. Sexuality in menopausal women. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016; 29(6):323–30.

Article13. Choukri MA, Conner TS, Haszard JJ, Harper MJ, Houghton LA. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms and psychological wellbeing in healthy adult women: a double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. J Nutr Sci. 2018; 7:e23.

Article14. Yalamanchili V, Gallagher JC. Treatment with hormone therapy and calcitriol did not affect depression in older postmenopausal women: no interaction with estrogen and vitamin D receptor genotype polymorphisms. Menopause. 2012; 19(6):697–703.

Article15. Ganji V, Milone C, Cody MM, McCarty F, Wang YT. Serum vitamin D concentrations are related to depression in young adult US population: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int Arch Med. 2010; 3:29.

Article16. Zhao G, Ford ES, Li C, Balluz LS. No associations between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone and depression among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2010; 104(11):1696–702.

Article17. Chung HK, Cho Y, Choi S, Shin MJ. The association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and depressive symptoms in Korean adults: findings from the fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010. PLoS One. 2014; 9(6):e99185.

Article18. Koo S, Park K. Associations of serum 25 (OH) D levels with depression and depressed condition in Korean adults: results from KNHANES 2008-2010. J Nutr Health. 2014; 47(2):113–23.

Article19. Rhee SJ, Lee H, Ahn YM. Serum vitamin D concentrations are associated with depressive symptoms in men: the Sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:756.

Article20. Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause: an update. Maturitas. 2016; 86:53–8.

Article21. Walf AA, Frye CA. ERbeta-selective estrogen receptor modulators produce antianxiety behavior when administered systemically to ovariectomized rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005; 30(9):1598–609.22. Arevalo MA, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. The neuroprotective actions of oestradiol and oestrogen receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015; 16(1):17–29.

Article23. Soares CN. Mood disorders in midlife women: understanding the critical window and its clinical implications. Menopause. 2014; 21(2):198–206.24. Ganji V, Shi Z, Alshami H, Ajina S, Albakri S, Jasim Z. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are inversely associated with body adiposity measurements but the association with bone mass is non-linear in postmenopausal women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2021; 212:105923.

Article25. Snijder MB, van Dam RM, Visser M, Deeg DJ, Dekker JM, Bouter LM, et al. Adiposity in relation to vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone levels: a population-based study in older men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005; 90(7):4119–23.

Article26. Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005; 29(1):21–30.27. Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, McNinch RW, Howie AJ, Stewart PM, et al. Extrarenal expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3)-1 alpha-hydroxylase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001; 86(2):888–94.28. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013; 202:100–7.

Article29. Silvers KM, Woolley CC, Hedderley D. Dietary supplement use in people being treated for depression. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006; 15(1):30–4.30. Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019; 365:1476.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Dietary factors associated with high serum ferritin levels in postmenopausal women with the Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V), 2010-2012

- The Association between Stress Level in Daily Life and Age at Natural Menopause in Korean Women: Outcomes of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2010-2012

- The Relationship of Water Intake and Health Status in Korean Adult: 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Association between Parity and Blood Pressure in Korean Women: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010-2012

- Relationship between age at last delivery and age at menopause: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey