Korean Circ J.

2022 Dec;52(12):853-864. 10.4070/kcj.2022.0294.

Establishment of an International Evidence Sharing Network Through Common Data Model for Cardiovascular Research

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Biomedical Systems Informatics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Institute for Innovation in Digital Healthcare, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Biomedical Informatics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 4Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ajou University Graduate School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- KMID: 2536787

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2022.0294

Abstract

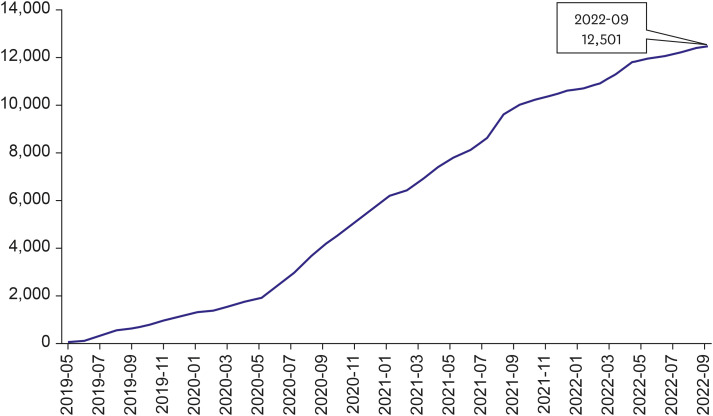

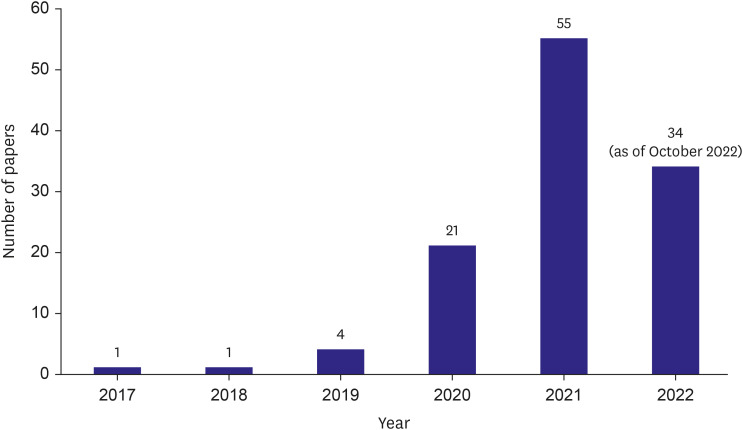

- A retrospective observational study is one of the most widely used research methods in medicine. However, evidence postulated from a single data source likely contains biases such as selection bias, information bias, and confounding bias. Acquiring enough data from multiple institutions is one of the most effective methods to overcome the limitations. However, acquiring data from multiple institutions from many countries requires enormous effort because of financial, technical, ethical, and legal issues as well as standardization of data structure and semantics. The Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) research network standardized 928 million unique records or 12% of the world’s population into a common structure and meaning and established a research network of 453 data partners from 41 countries around the world. OHDSI is a distributed research network wherein researchers do not own or directly share data but only analyzed results. However, sharing evidence without sharing data is difficult to understand. In this review, we will look at the basic principles of OHDSI, common data model, distributed research networks, and some representative studies in the cardiovascular field using the network. This paper also briefly introduces a Korean distributed research network named FeederNet.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Stang PE, Ryan PB, Racoosin JA, et al. Advancing the science for active surveillance: rationale and design for the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 153:600–606. PMID: 21041580.2. Overhage JM, Ryan PB, Reich CG, Hartzema AG, Stang PE. Validation of a common data model for active safety surveillance research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012; 19:54–60. PMID: 22037893.3. Hripcsak G, Duke JD, Shah NH, et al. Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI): opportunities for observational researchers. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015; 216:574–578. PMID: 26262116.4. Hripcsak G. OHDSI 2022 state of the community [Internet]. place unknown: Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics;2022. cited 2022 October 23. Available from: https://www.ohdsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/OHDSI2022-state-of-community-Hripcsak-FDA-Titans.pdf.5. Haendel MA, Chute CG, Robinson PN. Classification, ontology, and precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:1452–1462. PMID: 30304648.6. Seong Y, You SC, Ostropolets A, et al. Incorporation of Korean electronic data interchange vocabulary into observational medical outcomes partnership vocabulary. Healthc Inform Res. 2021; 27:29–38. PMID: 33611874.7. Yoon D, Ahn EK, Park MY, et al. Conversion and data quality assessment of electronic health record data at a Korean tertiary teaching hospital to a common data model for distributed network research. Healthc Inform Res. 2016; 22:54–58. PMID: 26893951.8. Blacketer C, Defalco FJ, Ryan PB, Rijnbeek PR. Increasing trust in real-world evidence through evaluation of observational data quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021; 28:2251–2257. PMID: 34313749.9. Hripcsak G, Ryan PB, Duke JD, et al. Characterizing treatment pathways at scale using the OHDSI network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016; 113:7329–7336. PMID: 27274072.10. Kostka K, Duarte-Salles T, Prats-Uribe A, et al. Unraveling COVID-19: a large-scale characterization of 4.5 million COVID-19 cases using CHARYBDIS. Clin Epidemiol. 2022; 14:369–384. PMID: 35345821.11. Brat GA, Weber GM, Gehlenborg N, et al. International electronic health record-derived COVID-19 clinical course profiles: the 4CE consortium. NPJ Digit Med. 2020; 3:109. PMID: 32864472.12. You SC, Jung S, Swerdel JN, et al. Comparison of first-line dual combination treatments in hypertension: real-world evidence from multinational heterogeneous cohorts. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:52–68. PMID: 31642211.13. Suchard MA, Schuemie MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Comprehensive comparative effectiveness and safety of first-line antihypertensive drug classes: a systematic, multinational, large-scale analysis. Lancet. 2019; 394:1816–1826. PMID: 31668726.14. Schuemie MJ, Ryan PB, Pratt N, et al. Principles of Large-scale Evidence Generation and Evaluation across a Network of Databases (LEGEND). J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020; 27:1331–1337. PMID: 32909033.15. Chan You S, Krumholz HM, Suchard MA, et al. Comprehensive comparative effectiveness and safety of first-line β-blocker monotherapy in hypertensive patients: a large-scale multicenter observational study. Hypertension. 2021; 77:1528–1538. PMID: 33775125.16. You SC, Rho Y, Bikdeli B, et al. Association of ticagrelor vs clopidogrel with net adverse clinical events in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2020; 324:1640–1650. PMID: 33107944.17. Reps JM, Schuemie MJ, Suchard MA, Ryan PB, Rijnbeek PR. Design and implementation of a standardized framework to generate and evaluate patient-level prediction models using observational healthcare data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018; 25:969–975. PMID: 29718407.18. Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2020; 3:119. PMID: 33015372.19. Dayan I, Roth HR, Zhong A, et al. Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021; 27:1735–1743. PMID: 34526699.20. Mamidi TK, Tran-Nguyen TK, Melvin RL, Worthey EA. Development of an individualized risk prediction model for COVID-19 using electronic health record data. Front Big Data. 2021; 4:675882. PMID: 34151259.21. Tong J, Luo C, Islam MN, et al. Distributed learning for heterogeneous clinical data with application to integrating COVID-19 data across 230 sites. NPJ Digit Med. 2022; 5:76. PMID: 35701668.22. Williams RD, Markus AF, Yang C, et al. Seek COVER: using a disease proxy to rapidly develop and validate a personalized risk calculator for COVID-19 outcomes in an international network. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022; 22:35. PMID: 35094685.23. Nestsiarovich A, Reps JM, Matheny ME, et al. Predictors of diagnostic transition from major depressive disorder to bipolar disorder: a retrospective observational network study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021; 11:642. PMID: 34930903.24. Jung H, Yoo S, Kim S, et al. Patient-Level fall risk prediction using the observational medical outcomes partnership’s common data model: pilot feasibility study. JMIR Med Inform. 2022; 10:e35104. PMID: 35275076.25. Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010; 340:c221. PMID: 20139215.26. Cooper H, Patall EA. The relative benefits of meta-analysis conducted with individual participant data versus aggregated data. Psychol Methods. 2009; 14:165–176. PMID: 19485627.27. Selmer R, Haglund B, Furu K, et al. Individual-based versus aggregate meta-analysis in multi-database studies of pregnancy outcomes: the Nordic example of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016; 25:1160–1169. PMID: 27193296.28. La Gamba F, Corrao G, Romio S, et al. Combining evidence from multiple electronic health care databases: performances of one-stage and two-stage meta-analysis in matched case-control studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017; 26:1213–1219. PMID: 28799196.29. Schuemie MJ, Chen Y, Madigan D, Suchard MA. Combining cox regressions across a heterogeneous distributed research network facing small and zero counts. Stat Methods Med Res. 2022; 31:438–450. PMID: 34841975.30. Marquis-Gravel G, Roe MT, Robertson HR, et al. Rationale and design of the Aspirin Dosing-A Patient-Centric Trial Assessing Benefits and Long-term Effectiveness (ADAPTABLE) trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020; 5:598–607. PMID: 32186653.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Data Sharing: a New Editorial Initiative from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Implications for the Editors' Network

- Statistics and Deep Belief Network-Based Cardiovascular Risk Prediction

- Development of a Jigsaw-based Maker Educational Model for Enhancing Sharing, Communication Competence and Digital Literacy

- Population data science: advancing the safe use of population data for public benefit

- Review of the Development and Application of Disease Network