Korean J Pain.

2022 Apr;35(2):140-151. 10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.140.

Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic properties of Origanum vulgare essential oil, rich with β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pharmacognosy, Yerevan State Medical University after M. Heratsi, Yerevan, Armenia

- 2Orbeli Institute of Physiology, Laboratory of Physiologically Active Substances Investigations, Yerevan, Armenia

- 3Orbeli Institute of Physiology, Laboratory of Tissue Engineering, Yerevan, Armenia

- 4Yerevan State University, Research Institute of Biology, Faculty of Biology, Yerevan, Armenia

- 5Yerevan State Medical University after M. Heratsi, Faculty of Pharmacy, Yerevan, Armenia

- KMID: 2527765

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.140

Abstract

- Background

Essential oils are of great interest for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. We aimed to study the content of the essential oil of the Origanum vulgare of the Armenian highlands (OVA) in different periods of vegetation and to investigate its antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in mice (in vivo) and cytotoxic action in cultured cells (in vitro). OVA essential oil was extracted from fresh plant material by hydro-distillation.

Methods

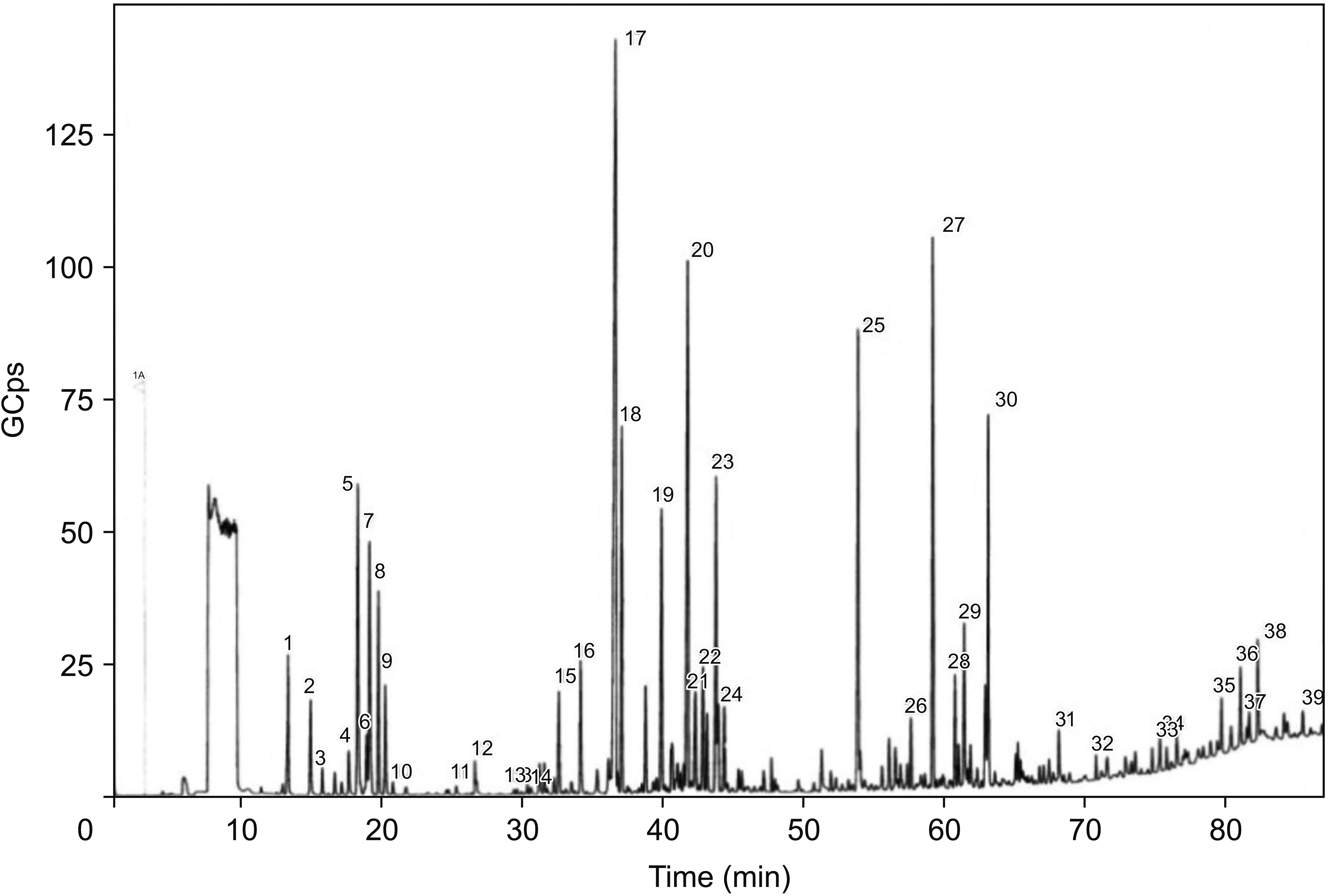

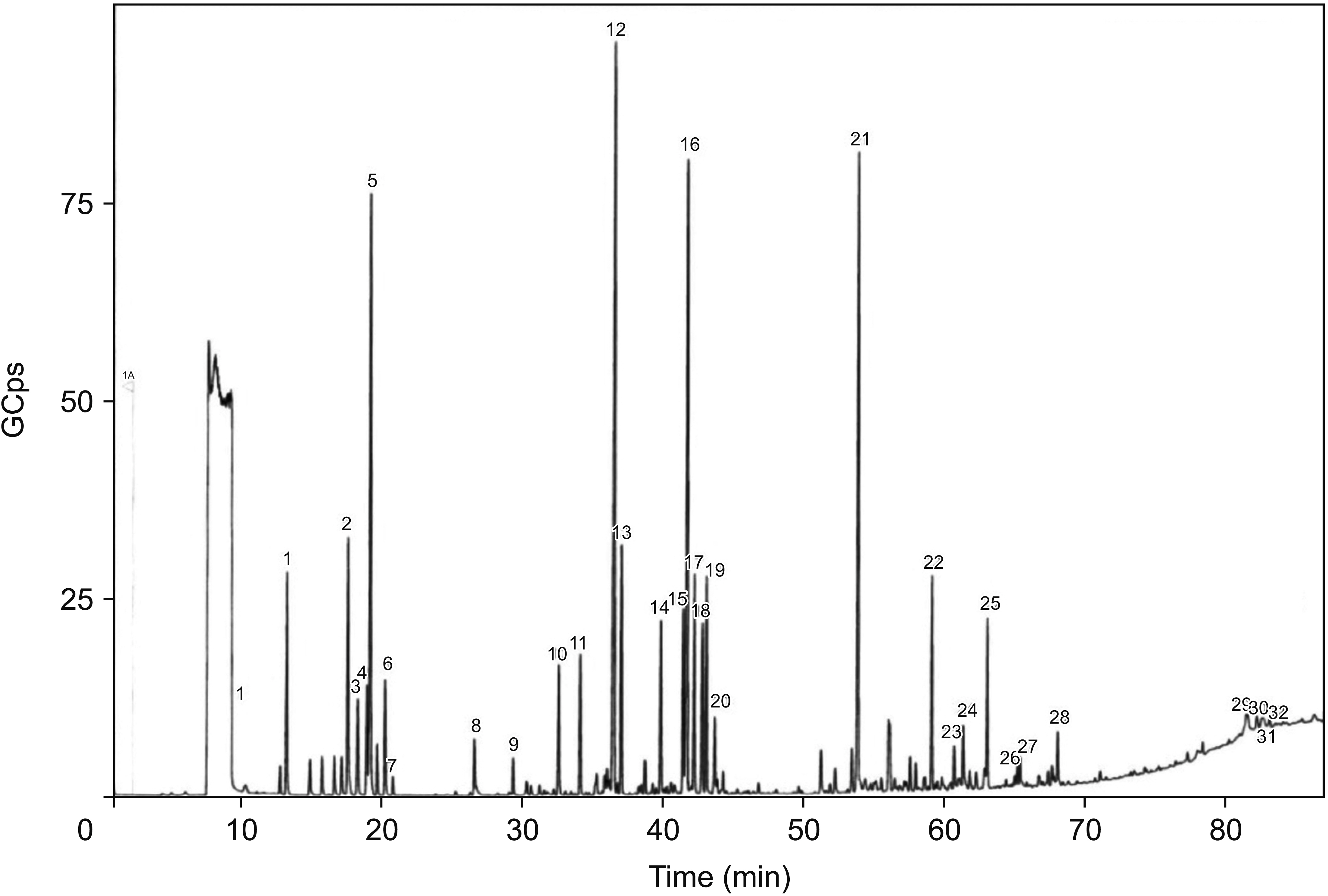

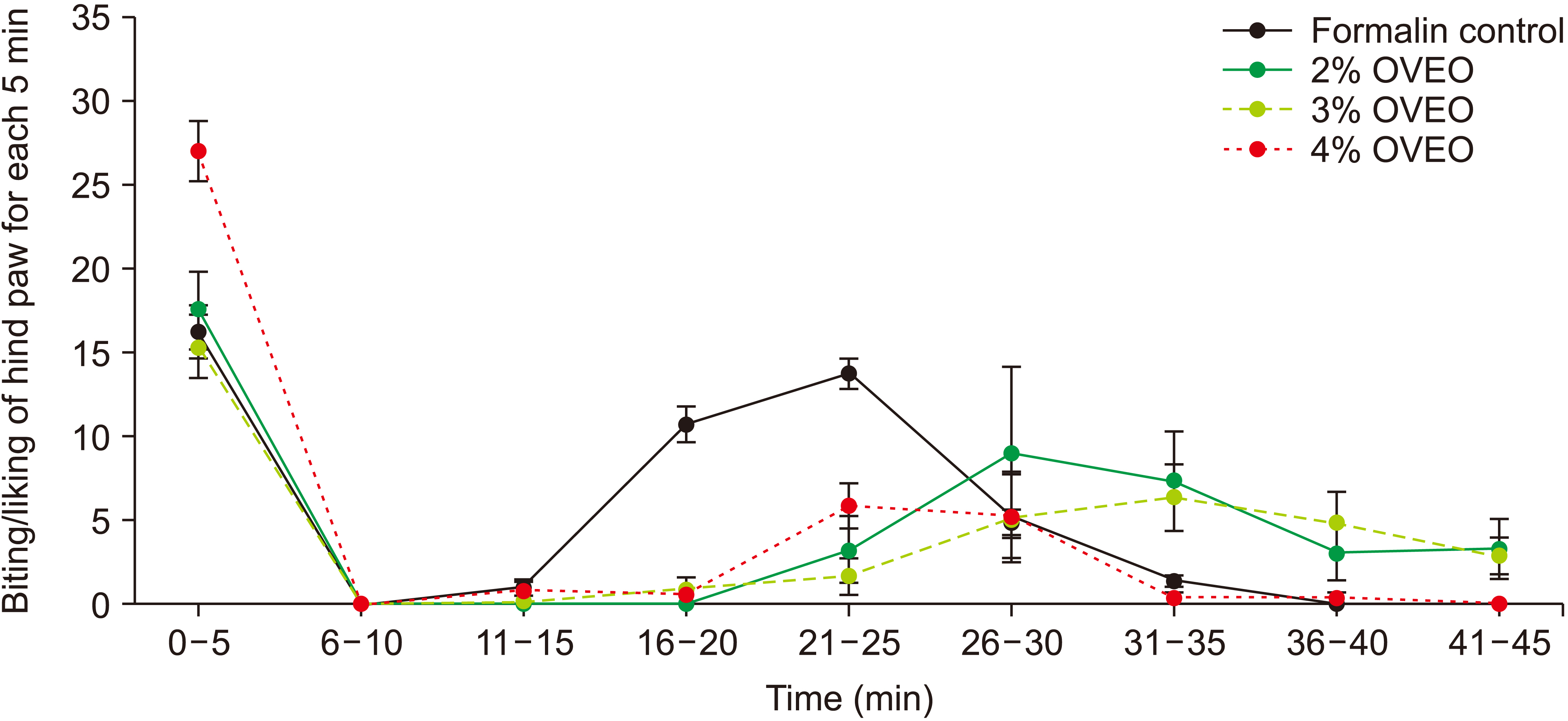

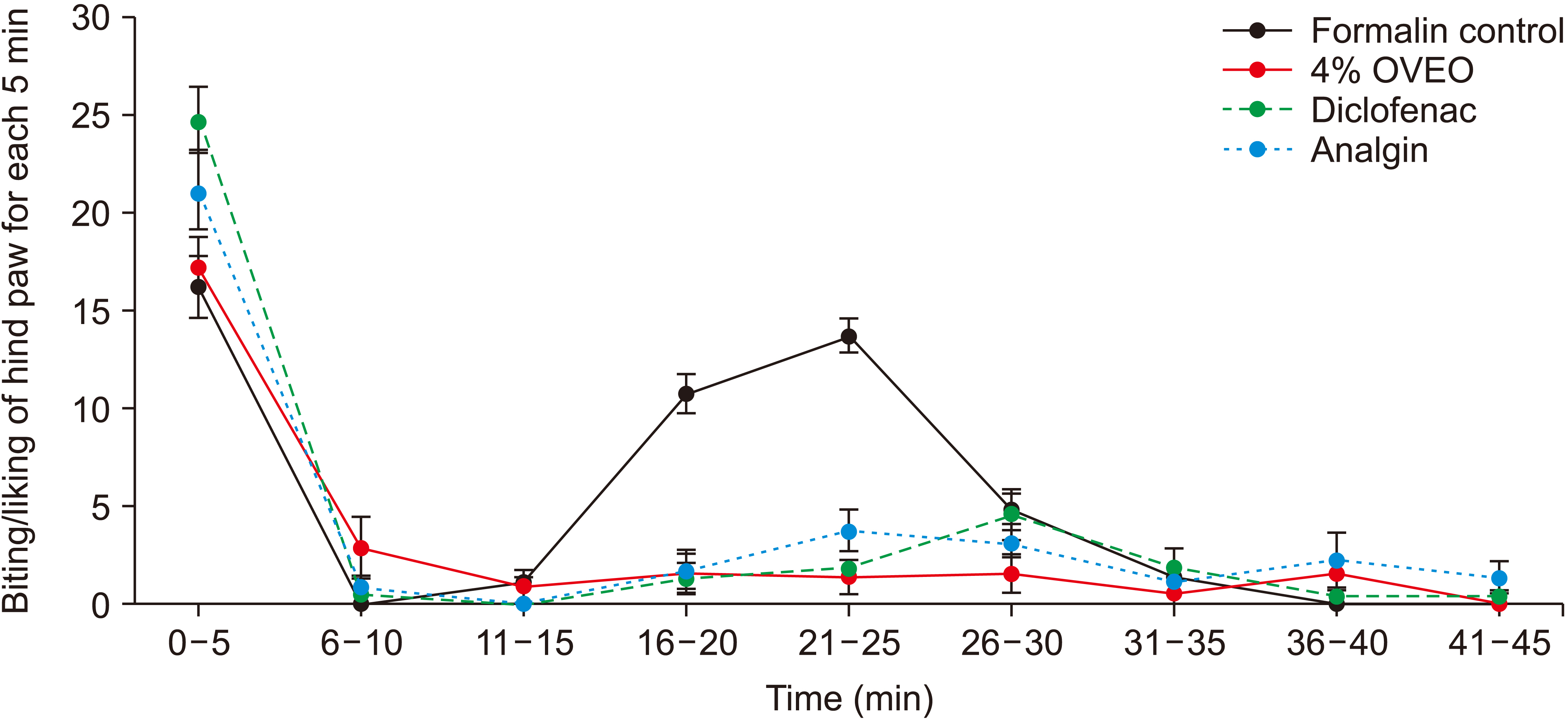

For OVA essential oil contents determination the gas chromatographymass spectrometry method was used. Formalin and hot plate tests and analysis of cell viability using the methyl-thiazolyl-tetrazolium (MTT) assay were used.

Results

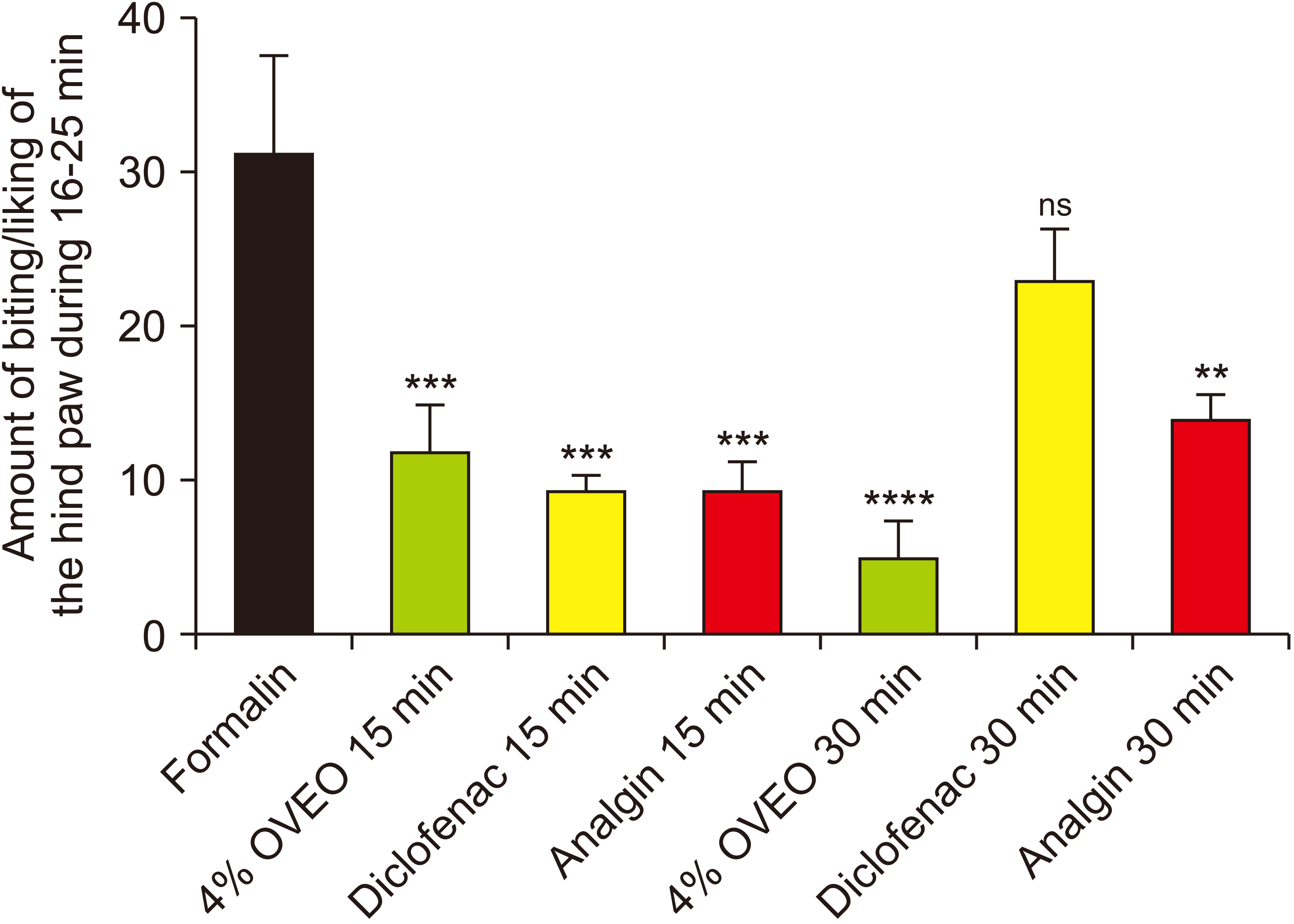

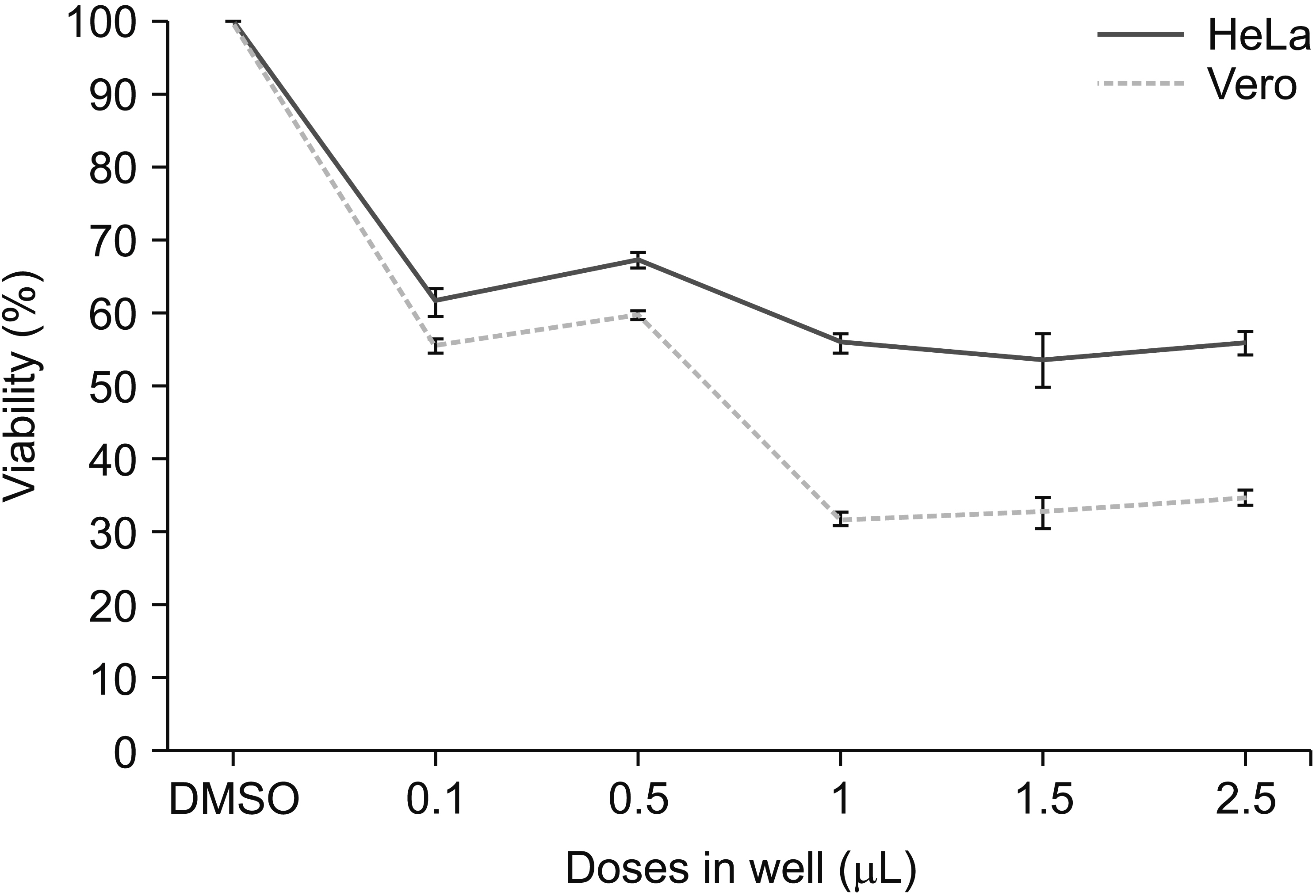

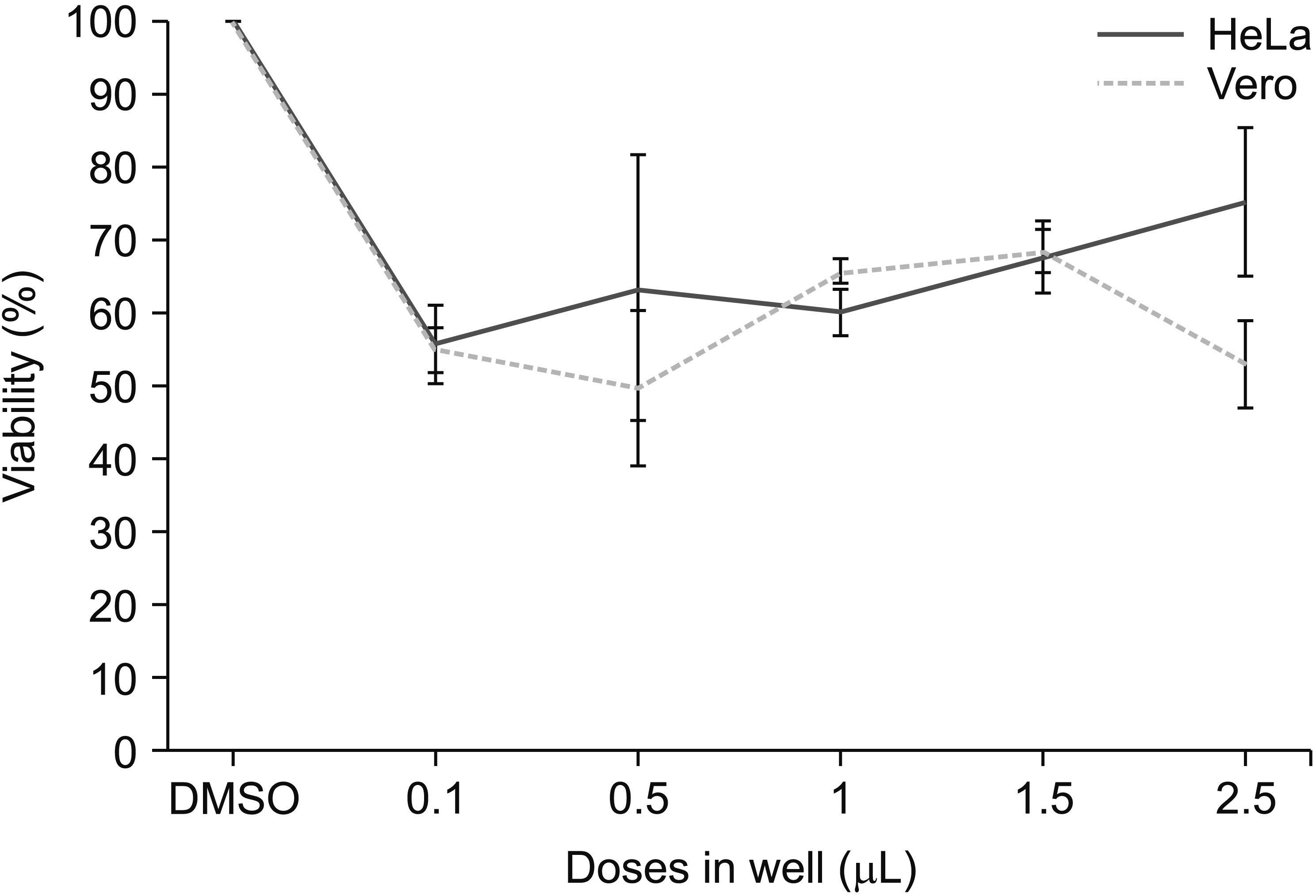

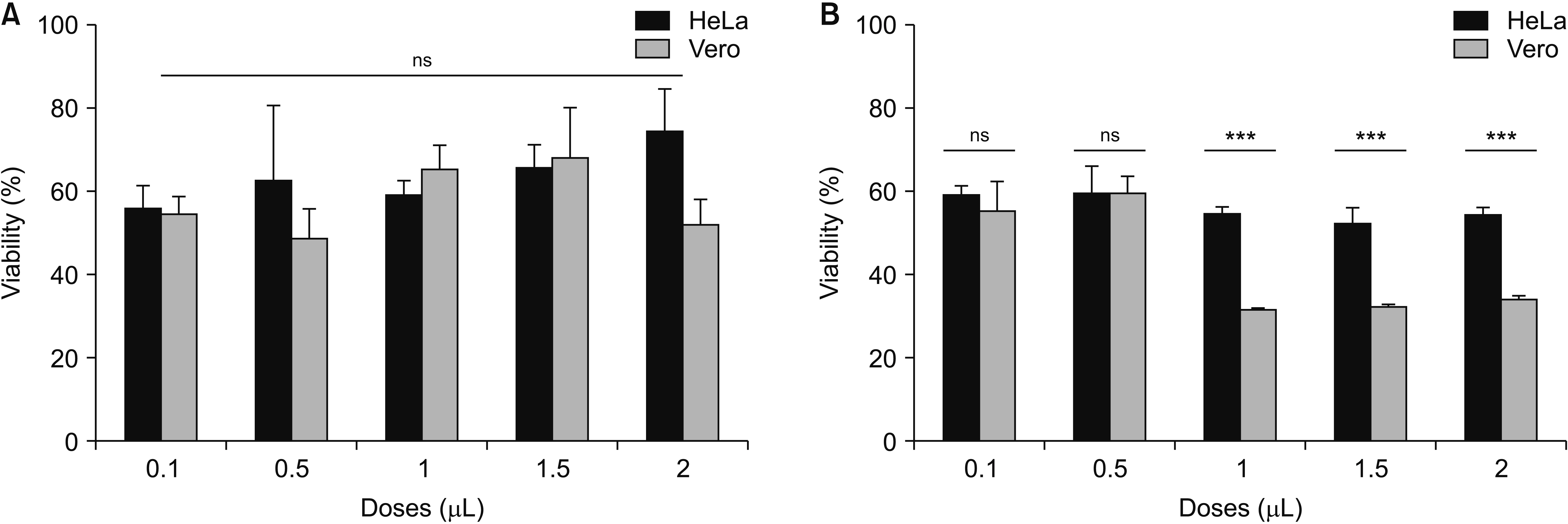

The maximal content of β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide in OVA essential oil was revealed in the period of blossoming (8.18% and 13.36%, correspondently). In the formalin test, 4% OVA essential oil solution (3.5 mg/mouse) exerts significant antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects (P = 0.003). MTT assay shows approximately 60% cytotoxicity in HeLa and Vero cells for 2.0 μL/mL OVA essential oil in media.

Conclusions

The wild oregano herb of Armenian highlands, harvested in the blossoming period, may be considered as a valuable source for developing pain-relieving preparations.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of a combined preparation based on the blunt-nosed viper’s venom and oregano essential oil

Lilya Mushegh Parsghyan, Armenuhi Vachagan Moghrovyan, Sona Samvel Poghosyan, Milena Ashot Babajanyan, Monica Armen Gaboyan, Armen Vaghinak Voskanyan, Anna Ashot Darbinyan

Korean J Pain. 2025;38(2):163-176. doi: 10.3344/kjp.24301.

Reference

-

1. Alwafa RA, Mudalal S, Mauriello G. 2021; Origanum syriacum L. (Za'atar), from raw to go: a review. Plants (Basel). 10:1001. DOI: 10.3390/plants10051001. PMID: 34067806. PMCID: PMC8156404. PMID: b581ff08daad4f8f95ca57a084455b36.2. Sahakyan N, Petrosyan M, Koss-Mikołajczyk I, Bartoszek A, Sad TG, Nasim MJ, et al. 2019; The Caucasian flora: a still-to-be-discovered rich source of antioxidants. Free Radic Res. 53(sup1):1153–62. DOI: 10.1080/10715762.2019.1648799. PMID: 31510813.

Article3. Kimera F, Sewilam H, Fouad WM, Suloma A. 2021; Efficient utilization of aquaculture effluents to maximize plant growth, yield, and essential oils composition of Origanum majorana cultivation. Ann Agric Sci. 66:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aoas.2020.11.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.aoas.2020.11.002.

Article4. Abrahamyan A, Barsevskis A, Crockett S, Melikyan A. 2014; Distribution of Origanum vulgare L. and population dynamics during the last decade in Armenia. J Life Sci (Libertyville). 8:690–8. https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=19347391-201408-201812030017-201812030017-690-698.5. Moghrovyan A, Sahakyan N, Babayan A, Chichoyan N, Petrosyan M, Trchounian A. 2019; Essential oil and ethanol extract of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) from Armenian flora as a natural source of terpenes, flavonoids and other phytochemicals with antiradical, antioxidant, metal chelating, tyrosinase inhibitory and antibacterial activity. Curr Pharm Des. 25:1809–16. DOI: 10.2174/1381612825666190702095612. PMID: 31267860.

Article6. Castronovo LM, Calonico C, Ascrizzi R, Del Duca S, Delfino V, Chioccioli S, et al. 2020; The cultivable bacterial microbiota associated to the medicinal plant Origanum vulgare L.: from antibiotic resistance to growth-inhibitory properties. Front Microbiol. 11:862. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00862. PMID: 32457726. PMCID: PMC7226918. PMID: e1c74d3f314540a88f1bef95d9f8a6f8.7. Council of Europe. 2005. European pharmacopoeia. 5th ed. Council of Europe;Strasbourg: https://www.worldcat.org/title/european-pharmacopoeia/oclc/608099208. DOI: 10.2174/1381612825666190702095612.8. Werker E, Putievsky E, Ravid U. 1985; The essential oils and glandular hairs in different chemotypes of Origanum vulgare L. Ann Bot. 55:793–801. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086958. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086958.

Article9. Leyva-López N, Gutiérrez-Grijalva EP, Vazquez-Olivo G, Heredia JB. 2017; Essential oils of oregano: biological activity beyond their antimicrobial properties. Molecules. 22:989. DOI: 10.3390/molecules22060989. PMID: 28613267. PMCID: PMC6152729.

Article10. Moghrovyan A. 2014. Qualitative analysis of Oregano ordinary herb (Herba Origani vulgaris) essential oil in various periods of vegetation. Paper presented at: Annual reporting science conference. 2014 Sep 15; Yerevan, Armenia. YSMU;Yerevan: p. 67–71.11. Dadalioglu I, Evrendilek GA. 2004; Chemical compositions and antibacterial effects of essential oils of Turkish oregano (Origanum minutiflorum), bay laurel (Laurus nobilis), Spanish lavender (Lavandula stoechas L.), and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) on common foodborne pathogens. J Agric Food Chem. 52:8255–60. DOI: 10.1021/jf049033e. PMID: 15612826.12. Sarmento-Neto JF, do Nascimento LG, Felipe CF, de Sousa DP. 2015; Analgesic potential of essential oils. Molecules. 21:E20. DOI: 10.3390/molecules21010020. PMID: 26703556. PMCID: PMC6273222.

Article13. Johnson SA, Rodriguez D, Allred K. 2020; A systematic review of essential oils and the endocannabinoid system: a connection worthy of further exploration. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020:8035301. DOI: 10.1155/2020/8035301. PMID: 32508955. PMCID: PMC7246407.

Article14. Rubino T, Zamberletti E, Parolaro D. 2015; Endocannabinoids and mental disorders. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 231:261–83. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-20825-1_9. PMID: 26408164.

Article15. Fidyt K, Fiedorowicz A, Strządała L, Szumny A. 2016; β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide-natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. Cancer Med. 5:3007–17. DOI: 10.1002/cam4.816. PMID: 27696789. PMCID: PMC5083753.

Article16. Turcotte C, Blanchet MR, Laviolette M, Flamand N. 2016; The CB2 receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:4449–70. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-016-2300-4. PMID: 27402121. PMCID: PMC5075023.

Article17. McKenna M, McDougall JJ. 2020; Cannabinoid control of neurogenic inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 177:4386–99. DOI: 10.1111/bph.15208. PMID: 33289534. PMCID: PMC7484507.

Article18. DiSabato DJ, Quan N, Godbout JP. 2016; Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J Neurochem. 139(Suppl 2):136–53. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.13607. PMID: 26990767. PMCID: PMC5025335.

Article19. World Health Organization. 2011. Quality control methods for herbal materials. Updated ed. World Health Organization;Geneva: p. 173. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44479. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-20825-1_9.20. National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Standard Reference Database 1A [computer program]. Version 2.4 Gaithersburg (MD).21. Kováts E. 1958; [Characterization of organic compounds by gas chromatography. Part 1. Retention indices of aliphatic halides, alcohols, aldehydes and ketones]. Helv Chim Acta. 41:1915–32. German.22. Dubuisson D, Dennis SG. 1977; The formalin test: a quantitative study of the analgesic effects of morphine, meperidine, and brain stem stimulation in rats and cats. Pain. 4:161–74. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. PMID: 564014.

Article23. Santos LH, Feres CA, Melo FH, Coelho MM, Nothenberg MS, Oga S, et al. 2004; Anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and ulcerogenic activity of a zinc-diclofenac complex in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 37:1205–13. DOI: 10.1590/S0100-879X2004000800011. PMID: 15273822.

Article24. Espejo EF, Mir D. 1993; Structure of the rat's behaviour in the hot plate test. Behav Brain Res. 56:171–6. DOI: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90035-O. PMID: 8240711.

Article25. Kumar P, Nagarajan A, Uchil PD. 2018; Analysis of cell viability by the MTT assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot095505. DOI: 10.1101/pdb.prot095505. PMID: 29858338.

Article26. Tjølsen A, Berge OG, Hunskaar S, Rosland JH, Hole K. 1992; The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain. 51:5–17. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90003-T.

Article27. Granados-Chinchilla F, Villegas E, Molina A, Arias C. 2016; Composition, chemical fingerprinting and antimicrobial assessment of Costa Rican Cultivated guavas (Psidium friedrichsthalianum (O. Berg) Nied. and Psidium guajava L.) essential oils from leaves and fruits. Nat Prod Chem Res. 4:236. https://www.kerwa.ucr.ac.cr/handle/10669/76578. DOI: 10.4172/2329-6836.1000236.28. Oliveira GLDS, Machado KC, Machado KC, da Silva APDSCL, Feitosa CM, de Castro Almeida FR. 2018; Non-clinical toxicity of β-caryophyllene, a dietary cannabinoid: absence of adverse effects in female Swiss mice. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 92:338–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.12.013. PMID: 29258925.29. Henry JL, Yashpal K, Pitcher GM, Coderre TJ. 1999; Physiological evidence that the 'interphase' in the formalin test is due to active inhibition. Pain. 82:57–63. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00033-0. PMID: 10422660.

Article30. Dahham SS, Tabana YM, Iqbal MA, Ahamed MB, Ezzat MO, Majid AS, et al. 2015; The anticancer, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene from the essential oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules. 20:11808–29. DOI: 10.3390/molecules200711808. PMID: 26132906. PMCID: PMC6331975.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Essential Oil of Marrubium vulgare: Chemical Composition and Biological Activities. A Review

- Inhibitory Effects of β-caryophyllene on Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Randomized Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study

- Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity Against Oral Bacteria by the Essential Oil of Artemisia iwayomogi

- Antimicrobial Activity of Some Essential Oils Against Microorganisms Deteriorating Fruit Juices

- Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Chrysanthemum indicum Against Oral Bacteria