Inhibition of Ceramide Accumulation in Podocytes by Myriocin Prevents Diabetic Nephropathy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Asan Institute for Life Science, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Medical Science and Asan Medical Institute of Convergence Science and Technology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Korea.

- KMID: 2513017

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2019.0063

Abstract

Background Ceramides are associated with metabolic complications including diabetic nephropathy in patients with diabetes. Recent studies have reported that podocytes play a pivotal role in the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Also, mitochondrial dysfunction is known to be an early event in podocyte injury. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that ceramide accumulation in podocytes induces mitochondrial damage through reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in patients with diabetic nephropathy.

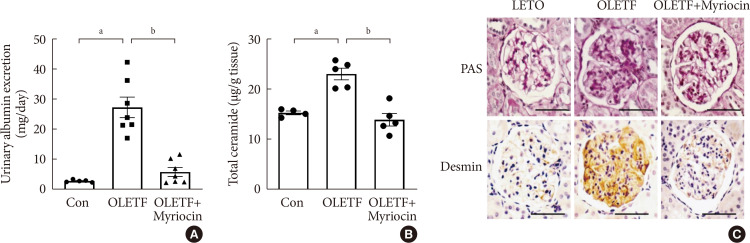

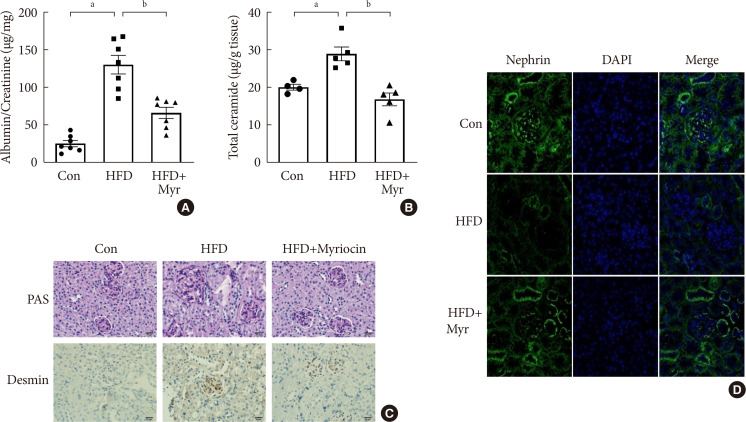

Methods We used Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats and high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice. We fed the animals either a control- or a myriocin-containing diet to evaluate the effects of the ceramide. Also, we assessed the effects of ceramide on intracellular ROS generation and on podocyte autophagy in cultured podocytes.

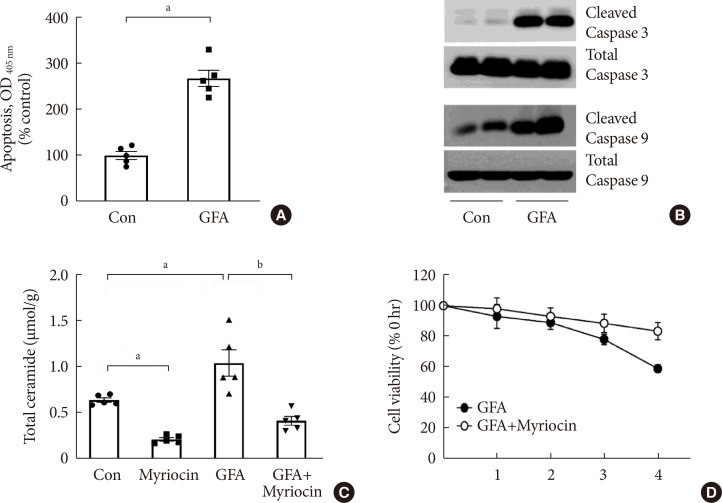

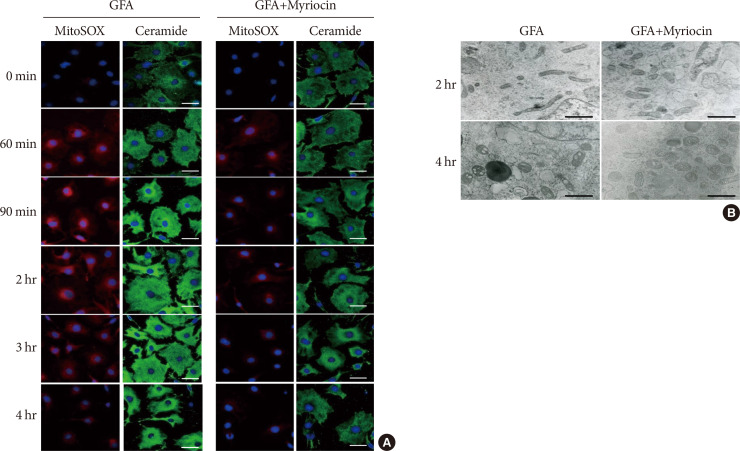

Results OLETF rats and HFD-fed mice showed albuminuria, histologic features of diabetic nephropathy, and podocyte injury, whereas myriocin treatment effectively treated these abnormalities. Cultured podocytes exposed to agents predicted to be risk factors (high glucose, high free fatty acid, and angiotensin II in combination [GFA]) showed an increase in ceramide accumulation and ROS generation in podocyte mitochondria. Pretreatment with myriocin reversed GFA-induced mitochondrial ROS generation and prevented cell death. Myriocin-pretreated cells were protected from GFA-induced disruption of mitochondrial integrity.

Conclusion We showed that mitochondrial ceramide accumulation may result in podocyte damage through ROS production. Therefore, this signaling pathway could become a pharmacological target to abate the development of diabetic kidney disease.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Harjutsalo V, Groop PH. Epidemiology and risk factors for diabetic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014; 21:260–266. PMID: 24780453.

Article2. Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, Chiang JL, de Boer IH, Goldstein-Fuchs J, Hirsch IB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Narva AS, Navaneethan SD, Neumiller JJ, Patel UD, Ratner RE, Whaley-Connell AT, Molitch ME. Diabetic kidney disease: a report from an ADA Consensus Conference. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37:2864–2883. PMID: 25249672.

Article3. Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008; 57:1446–1454. PMID: 18511445.

Article4. Johnston CI, Fabris B, Jandeleit K. Intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in renal physiology and pathophysiology. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993; 42:S59–S63. PMID: 8361131.5. Bhatti AB, Usman M. Drug targets for oxidative podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy. Cureus. 2015; 7:e393. PMID: 26798569.

Article6. Jiang T, Wang Z, Proctor G, Moskowitz S, Liebman SE, Rogers T, Lucia MS, Li J, Levi M. Diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice causes increased renal lipid accumulation and glomerulosclerosis via a sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:32317–32325. PMID: 16046411.

Article8. Adams JM 2nd, Pratipanawatr T, Berria R, Wang E, DeFronzo RA, Sullards MC, Mandarino LJ. Ceramide content is increased in skeletal muscle from obese insulin-resistant humans. Diabetes. 2004; 53:25–31. PMID: 14693694.

Article9. Kennedy A, Martinez K, Chuang CC, LaPoint K, McIntosh M. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: mechanisms of action and implications. J Nutr. 2009; 139:1–4. PMID: 19056664.

Article10. Haus JM, Kashyap SR, Kasumov T, Zhang R, Kelly KR, Defronzo RA, Kirwan JP. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009; 58:337–343. PMID: 19008343.

Article11. Boini KM, Zhang C, Xia M, Poklis JL, Li PL. Role of sphingolipid mediator ceramide in obesity and renal injury in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010; 334:839–846. PMID: 20543095.

Article12. Merscher S, Fornoni A. Podocyte pathology and nephropathy: sphingolipids in glomerular diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014; 5:127. PMID: 25126087.

Article13. Srivastava SP, Shi S, Koya D, Kanasaki K. Lipid mediators in diabetic nephropathy. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2014; 7:12. PMID: 25206927.

Article14. Chavez JA, Summers SA. A ceramide-centric view of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012; 15:585–594. PMID: 22560211.

Article15. Yi F, Zhang AY, Li N, Muh RW, Fillet M, Renert AF, Li PL. Inhibition of ceramide-redox signaling pathway blocks glomerular injury in hyperhomocysteinemic rats. Kidney Int. 2006; 70:88–96. PMID: 16688115.

Article16. Mundel P, Kriz W. Structure and function of podocytes: an update. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1995; 192:385–397. PMID: 8546330.

Article17. Reidy K, Kang HM, Hostetter T, Susztak K. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124:2333–2340. PMID: 24892707.

Article18. Abe Y, Sakairi T, Kajiyama H, Shrivastav S, Beeson C, Kopp JB. Bioenergetic characterization of mouse podocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010; 299:C464–C476. PMID: 20445170.

Article19. Zhu C, Huang S, Yuan Y, Ding G, Chen R, Liu B, Yang T, Zhang A. Mitochondrial dysfunction mediates aldosterone-induced podocyte damage: a therapeutic target of PPARγ. Am J Pathol. 2011; 178:2020–2031. PMID: 21514419.20. Tsuruoka S, Hiwatashi A, Usui J, Yamagata K. The mitochondrial SIRT1-PGC-1α axis in podocyte injury. Kidney Int. 2012; 82:735–736. PMID: 22975995.

Article21. Lin JS, Susztak K. Podocytes: the weakest link in diabetic kidney disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2016; 16:45. PMID: 27053072.

Article22. Yoo TH, Pedigo CE, Guzman J, Correa-Medina M, Wei C, Villarreal R, Mitrofanova A, Leclercq F, Faul C, Li J, Kretzler M, Nelson RG, Lehto M, Forsblom C, Groop PH, Reiser J, Burke GW, Fornoni A, Merscher S. Sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b expression levels determine podocyte injury phenotypes in glomerular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 26:133–147. PMID: 24925721.

Article23. Shankland SJ, Pippin JW, Reiser J, Mundel P. Podocytes in culture: past, present, and future. Kidney Int. 2007; 72:26–36. PMID: 17457377.

Article24. Millon SR, Ostrander JH, Yazdanfar S, Brown JQ, Bender JE, Rajeha A, Ramanujam N. Preferential accumulation of 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX in breast cancer: a comprehensive study on six breast cell lines with varying phenotypes. J Biomed Opt. 2010; 15:018002. PMID: 20210488.

Article25. Fukuzawa Y, Watanabe Y, Inaguma D, Hotta N. Evaluation of glomerular lesion and abnormal urinary findings in OLETF rats resulting from a long-term diabetic state. J Lab Clin Med. 1996; 128:568–578. PMID: 8960640.

Article26. Yang G, Badeanlou L, Bielawski J, Roberts AJ, Hannun YA, Samad F. Central role of ceramide biosynthesis in body weight regulation, energy metabolism, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 297:E211–E224. PMID: 19435851.

Article27. Kitada M, Ogura Y, Koya D. Rodent models of diabetic nephropathy: their utility and limitations. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016; 9:279–290. PMID: 27881924.

Article28. Deji N, Kume S, Araki S, Soumura M, Sugimoto T, Isshiki K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Sakaguchi M, Koya D, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A, Uzu T. Structural and functional changes in the kidneys of high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009; 296:F118–F126. PMID: 18971213.

Article29. Jones N, Blasutig IM, Eremina V, Ruston JM, Bladt F, Li H, Huang H, Larose L, Li SS, Takano T, Quaggin SE, Pawson T. Nck adaptor proteins link nephrin to the actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes. Nature. 2006; 440:818–823. PMID: 16525419.

Article30. Jefferson JA, Shankland SJ, Pichler RH. Proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease: a mechanistic viewpoint. Kidney Int. 2008; 74:22–36. PMID: 18418356.

Article31. Villena J, Henriquez M, Torres V, Moraga F, Diaz-Elizondo J, Arredondo C, Chiong M, Olea-Azar C, Stutzin A, Lavandero S, Quest AF. Ceramide-induced formation of ROS and ATP depletion trigger necrosis in lymphoid cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 44:1146–1160. PMID: 18191646.

Article32. Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:580–591. PMID: 18256393.

Article33. Kashihara N, Haruna Y, Kondeti VK, Kanwar YS. Oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Med Chem. 2010; 17:4256–4269. PMID: 20939814.

Article34. Andrieu-Abadie N, Gouaze V, Salvayre R, Levade T. Ceramide in apoptosis signaling: relationship with oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001; 31:717–728. PMID: 11557309.

Article35. Pagadala M, Kasumov T, McCullough AJ, Zein NN, Kirwan JP. Role of ceramides in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 23:365–371. PMID: 22609053.

Article36. Véret J, Bellini L, Giussani P, Ng C, Magnan C, Le Stunff H. Roles of sphingolipid metabolism in pancreatic β cell dysfunction induced by lipotoxicity. J Clin Med. 2014; 3:646–662. PMID: 26237395.

Article37. Quillet-Mary A, Jaffrezou JP, Mansat V, Bordier C, Naval J, Laurent G. Implication of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide generation in ceramide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272:21388–21395. PMID: 9261153.

Article38. Darshi M, Mendiola VL, Mackey MR, Murphy AN, Koller A, Perkins GA, Ellisman MH, Taylor SS. ChChd3, an inner mitochondrial membrane protein, is essential for maintaining crista integrity and mitochondrial function. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286:2918–2932. PMID: 21081504.

Article39. Cogliati S, Enriquez JA, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial cristae: where beauty meets functionality. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016; 41:261–273. PMID: 26857402.

Article40. Kurek K, Piotrowska DM, Wiesiolek-Kurek P, Lukaszuk B, Chabowski A, Gorski J, Zendzian-Piotrowska M. Inhibition of ceramide de novo synthesis reduces liver lipid accumulation in rats with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2014; 34:1074–1083. PMID: 24106929.

Article41. Patil MR, Mishra A, Jain N, Gutch M, Tewari R. Weight loss for reduction of proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy: comparison with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. Indian J Nephrol. 2013; 23:108–113. PMID: 23716916.

Article42. Yang H, Zhao B, Liao C, Zhang R, Meng K, Xu J, Jiao J. High glucose-induced apoptosis in cultured podocytes involves TRPC6-dependent calcium entry via the RhoA/ROCK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 434:394–400. PMID: 23570668.

Article43. Yang Y, Yang Q, Yang J, Ma Y, Ding G. Angiotensin II induces cholesterol accumulation and injury in podocytes. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:10672. PMID: 28878222.

Article44. Thrush AB, Chabowski A, Heigenhauser GJ, McBride BW, Or-Rashid M, Dyck DJ. Conjugated linoleic acid increases skeletal muscle ceramide content and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight, non-diabetic humans. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007; 32:372–382. PMID: 17510671.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pathology identifies glomerular treatment targets in diabetic nephropathy

- The Role of Glomerular Podocytes in Diabetic Nephropathy

- Autophagy: A Novel Therapeutic Target for Diabetic Nephropathy

- Pathophysiology of Diabetic Nephropathy

- Diabetic conditions modulate the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase of podocytes