Investig Clin Urol.

2020 Feb;61(Suppl 1):S57-S63. 10.4111/icu.2020.61.S1.S57.

Tobacco use, immunosuppressive, chronic pain, and psychiatric conditions are prevalent in women with symptomatic mesh complications undergoing mesh removal surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Section of Urology and Renal Transplantation, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA. Una.Lee@virginiamason.org

- 2Department of Urology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

- KMID: 2469127

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2020.61.S1.S57

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To identify demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with symptomatic pelvic floor mesh complications who underwent mesh removal at our academic medical center. The secondary goal was to determine patient-reported outcomes after mesh removal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective review of consecutive patients from 2011-2016 undergoing removal of mesh graft for treatment of symptomatic mesh-related complications. Patient demographics, comorbidities, symptoms, and mesh factors were evaluated. Outcomes after explant were determined by the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and a Likert satisfaction scale.

RESULTS

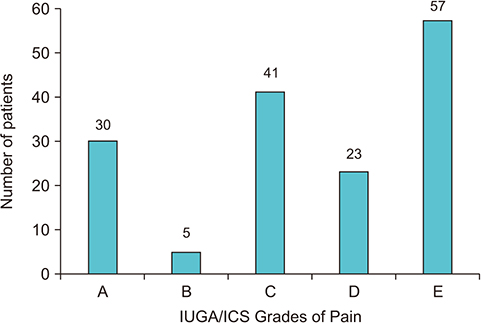

One hundred fifty-six symptomatic patients underwent complete or partial pelvic floor mesh removal during the study period. Mid-urethral slings comprised 86% of explanted mesh grafts. Mesh exposure or erosion was identified in 72% of patients. Eighty-one percent of patients presented with pain, and 35% reported pain in the absence of exposure or erosion. Pre-operative comorbidities included psychiatric disease (54.5%), chronic pain (34.0%), irritable bowel syndrome (20.5%) and fibromyalgia (9.6%). Forty-three percent of patients reported current or past tobacco use. At mean follow-up of 14 months, 68% of responding patients reported improvement on the Patient Global Impression of Improvement after surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

This research identified tobacco use, and psychiatric, immunosuppressive, and chronic pain conditions as prevalent in this cohort of patients undergoing mesh removal. Surgical removal can improve presenting symptoms, including for patients with pain in the absence of other indications.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Celebrating the 60th anniversary of Investigative and Clinical Urology

Kwangsung Park

Investig Clin Urol. 2020;61(Suppl 1):S1-S2. doi: 10.4111/icu.2020.61.S1.S1.

Reference

-

1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 89:501–506.

Article2. Jonsson Funk M, Siddiqui NY, Kawasaki A, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes after stress urinary incontinence surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:83–90.

Article3. Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014; 20:123–125.

Article4. Stanford E, Moen M. Patient safety communication from the Food and Drug Administration regarding transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011; 18:689–691.

Article5. Menchen LC, Wein AJ, Smith AL. An appraisal of the Food and Drug Administration warning on urogynecologic surgical mesh. Curr Urol Rep. 2012; 13:231–239.

Article6. Barski D, Otto T, Gerullis H. Systematic review and classification of complications after anterior, posterior, apical, and total vaginal mesh implantation for prolapse repair. Surg Technol Int. 2014; 24:217–224.7. Kirby AC, Nager CW. Indications, contraindications, and complications of mesh in the surgical treatment of urinary incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 56:257–275.

Article8. Marks BK, Goldman HB. Controversies in the management of mesh-based complications: a urology perspective. Urol Clin North Am. 2012; 39:419–428.9. Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, Cundiff G, Richter H, Gantz M, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013; 309:2016–2024.

Article10. Paine M, Harnsberger JR, Whiteside JL. Transrectal mesh erosion remote from sacrocolpopexy: management and comment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 203:e11–e13.

Article11. Sarlos D, Aigmueller T, Schaer G. A technique of laparoscopic mesh excision from the bladder after sacrocolpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 212:403.e1–403.e3.

Article12. Takacs EB, Kreder KJ. Sacrocolpopexy: surgical technique, outcomes, and complications. Curr Urol Rep. 2016; 17:90.

Article13. Ulrich D, Bjelic-Radisic V, Höllein A, Trutnovsky G, Tamussino K, Aigmüller T. Quality of life and objective outcome assessment in women with tape division after surgery for stress urinary incontinence. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0174628.

Article14. Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Cosson M, Davila GW, Deprest J, et al. International Urogynecological Association. International Continence Society, Joint IUGA/ICS Working Group on Complications Terminology. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011; 30:2–12.15. Hou JC, Alhalabi F, Lemack GE, Zimmern PE. Outcome of transvaginal mesh and tape removed for pain only. J Urol. 2014; 192:856–860.

Article16. Danford JM, Osborn DJ, Reynolds WS, Biller DH, Dmochowski RR. Postoperative pain outcomes after transvaginal mesh revision. Int Urogynecol J. 2015; 26:65–69.

Article17. Geller EJ, Babb E, Nackley AG, Zolnoun D. Incidence and risk factors for pelvic pain after mesh implant surgery for the treatment of pelvic floor disorders. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017; 24:67–73.

Article18. Rechberger T, Nowakowski Ł, Rechberger E, Ziętek A, Winkler I, Miotła P. Prevalence of common comorbidities among urogynaecological patients. Ginekol Pol. 2016; 87:342–346.

Article19. Araco F, Gravante G, Sorge R, De Vita D, Piccione E. Risk evaluation of smoking and age on the occurrence of postoperative erosions after transvaginal mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapses. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008; 19:473–479.

Article20. Kobashi KC, Albo ME, Dmochowski RR, Ginsberg DA, Goldman HB, Gomelsky A, et al. Surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2017; 198:875–883.

Article21. Crosby EC, Abernethy M, Berger MB, DeLancey JO, Fenner DE, Morgan DM. Symptom resolution after operative management of complications from transvaginal mesh. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 123:134–139.

Article22. Jong K, Popat S, Christie A, Zimmern PE. Is pain relief after vaginal mesh and/or sling removal durable long term? Int Urogynecol J. 2018; 29:859–864.

Article23. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163:2433–2445.24. Katona C, Peveler R, Dowrick C, Wessely S, Feinmann C, Gask L, et al. Pain symptoms in depression: definition and clinical significance. Clin Med (Lond). 2005; 5:390–395.

Article25. Britteon P, Cullum N, Sutton M. Association between psychological health and wound complications after surgery. Br J Surg. 2017; 104:769–776.

Article26. Ghoneim MM, O'Hara MW. Depression and postoperative complications: an overview. BMC Surg. 2016; 16:5.

Article27. Rosenberger PH, Jokl P, Ickovics J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006; 14:397–405.

Article28. Larouche M, Brotto LA, Koenig NA, Lee T, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Depression, anxiety, and pelvic floor symptoms before and after surgery for pelvic floor dysfunction. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018; 04. 23. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000582.

Article29. Welk B, Reid J, Kelly E, Wu YM. Association of transvaginal mesh complications with the risk of new-onset depression or self-harm in women with a midurethral sling. JAMA Surg. 2019; 154:358–360.

Article30. Thomas D, Demetres M, Anger JT, Chughtai B. Histologic inflammatory response to transvaginal polypropylene mesh: a systematic review. Urology. 2018; 111:11–22.

Article31. Nolfi AL, Brown BN, Liang R, Palcsey SL, Bonidie MJ, Abramowitch SD, et al. Host response to synthetic mesh in women with mesh complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 215:206.e1–206.e8.

Article32. Hill AJ, Unger CA, Solomon ER, Brainard JA, Barber MD. Histopathology of excised midurethral sling mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2015; 26:591–595.

Article33. Rogo-Gupta L, Grisales T, Huynh L, Rodríguez LV, Raz S. Symptom improvement after prolapse and incontinence graft removal in a case series of 306 patients. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015; 21:319–324.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Management of Infected Mesh after Laparoscopic Incisional Hernia Repair

- Transmural Mesh Migration From the Abdominal Wall to the Rectum After Hernia Repair Using a Prolene Mesh: A Case Report

- A clinical study on the trocar-guided mesh repair system for pelvic organ prolapse surgery

- Outcomes of Transurethral Removal of Intravesical or Intraurethral Mesh Following Midurethral Sling Surgery

- Vaginal Approaches Using Synthetic Mesh to Treat Pelvic Organ Prolapse