Transl Clin Pharmacol.

2019 Dec;27(4):127-133. 10.12793/tcp.2019.27.4.127.

The problem of medicating women like the men: conceptual discussion of menstrual cycle-dependent psychopharmacology

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department Obstetrics and Gynecology, Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul 02841, Korea. tkim@kumc.or.kr

- 2Department Psychiatry, New Jersey Medical School, UMDNJ, NJ, USA.

- KMID: 2467966

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12793/tcp.2019.27.4.127

Abstract

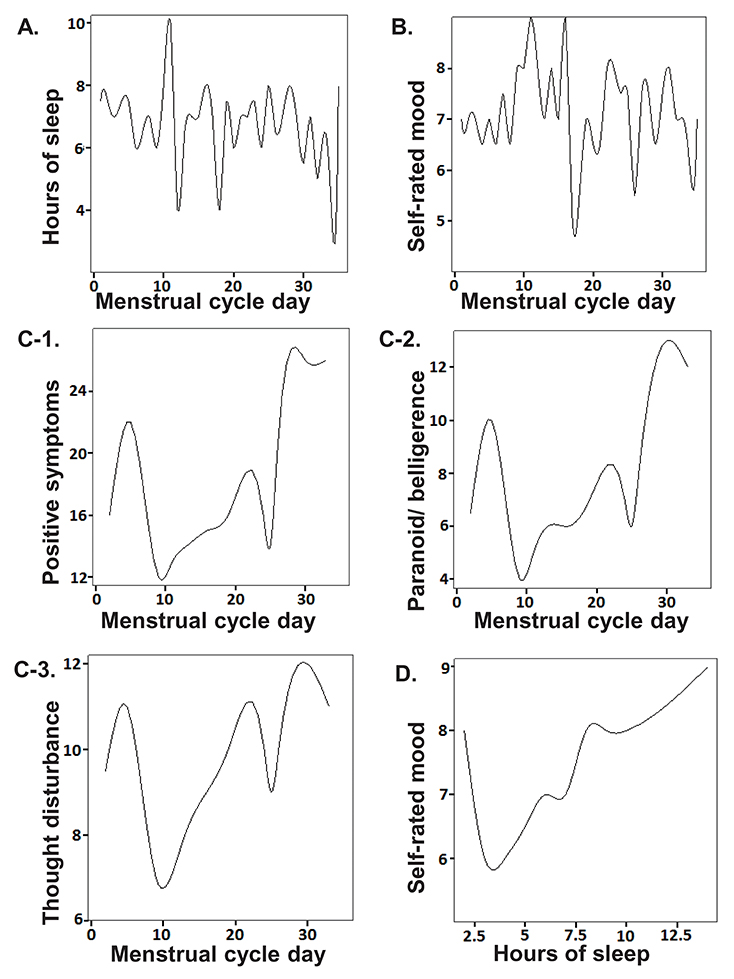

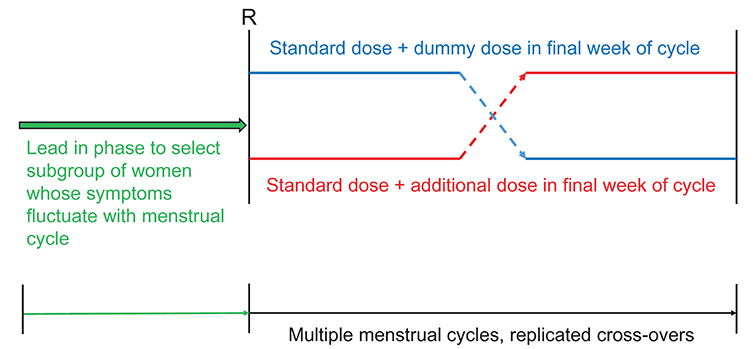

- While hormonal changes during the ovulatory cycles affect multiple body systems, medical management, including medication dosing remains largely uniform between the sexes. Little is known about sex-specific pharmacology in women. Although hormonal fluctuations of the normal menstruating process alters women's physiology and brain biochemistry, medication dosing does not consider such cyclical changes. Using schizophrenia as an example, this paper illustrates how a woman's clinical symptoms can change throughout the ovulatory cycle, leading to fluctuations in medication responses. Effects of sex steroids on the brain, clinical pharmacology are discussed. Effective medication dose may be different at different phases of the menstrual cycle. Further research is needed to better understand optimal treatment strategies in reproductive women; we present a potential clinical trial design for examining optimal medication dosing strategies for conditions that have menstruation related clinical fluctuations.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lingjaerde P, Bredland R. Hyperestrogenic cyclic psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1954; 29:355–364.

Article2. Felthous AR, Robinson DB, Conroy RW. Prevention of recurrent menstrual psychosis by an oral contraceptive. Am J Psychiatry. 1980; 137:245–246.

Article3. Endo M, Daiguji M, Asano Y, Yamashita I, Takahashi S. Periodic psychosis recurring in association with menstrual cycle. J Clin Psychiatry. 1978; 39:456–466.4. Berlin FS, Bergey GK, Money J. Periodic psychosis of puberty: a case report. Am J Psychiatry. 1982; 139:119–120.

Article5. Dalton K. Menstruation and acute psychiatric illnesses. Br Med J. 1959; 1:148–149.

Article6. Riecher-Rössler A, Häfner H, Dütsch-Strobel A, Oster M, Stumbaum M, van Gülick-Bailer M, et al. Further evidence for a specific role of estradiol in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1994; 36:492–494.

Article7. Yum SK, Kim T, Hwang MY. Polycystic ovaries is a disproportionate signal in pharmacovigilance data mining of second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2014; 158:275–276. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.003.

Article8. Byrnes EM, Bridges RS, Scanlan VF, Babb JA, Byrnes JJ. Sensorimotor gating and dopamine function in postpartum rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007; 32:1021–1031.

Article9. Dazzi L, Seu E, Cherchi G, Barbieri PP, Matzeu A, Biggio G. Estrous cycle-dependent changes in basal and ethanol-induced activity of cortical dopaminergic neurons in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007; 32:892–901.

Article10. Gogos A, Nathan PJ, Guille V, Croft RJ, van den Buuse M. Estrogen prevents 5-HT1A receptor-induced disruptions of prepulse inhibition in healthy women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006; 31:885–889.

Article11. Riecher-Rössler A. Oestrogen effects in schizophrenia and their potential therapeutic implications--review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002; 111–118.12. Behrens S, Hafner H, DeVry J, Gattaz WF. Estradiol attenuates dopamine-mediated behaviour in rats: implications for sex differences in schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992; 25:96.13. Kulkarni J, de Castella A, Smith D, Taffe J, Keks N, Copolov D. A clinical trial of the effects of estrogen in acutely psychotic women. Schizophr Res. 1996; 20:247–252.

Article14. Kulkarni J, Riedel A, de Castella AR, Fitzgerald PB, Rolfe TJ, Taffe J, et al. A clinical trial of adjunctive oestrogen treatment in women with schizophrenia. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002; 5:99–104.

Article15. Seeman MV, Lang M. The role oestrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull. 1990; 16:185–194.16. Kelly DL, Conley RR, Tamminga CA. Differential olanzapine plasma concentrations by sex in a fixed-dose study. Schizophr Res. 1999; 40:101–104.

Article17. Usall J, Barcelo M, Marquez M. Women and schizophrenia: sex-based pharmacotherapy. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2006; 2:95–101.

Article18. Miners JO, McKinnon RA. CYP1A. In : Levy RH, Thummel KE, Trager WF, Hansten PD, Eichelbaum M, editors. Metabolic Drug Interactions. . PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2000. p. 66.19. Riecher-Rossler A, Hofner H, Stumbaum M, Maurer K, Schmidt R. Can estradiol modulate schizophrenic symptomatology? Schizophr Bull. 1994; 20:203–214.

Article20. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Meltzer-Brody S, Harsh V. The neurobiology of menstrual-cycle related mood disorders. In : Charney DS, Nestler EJ, editors. Neurobiology of Mental Illness. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;2009. p. 544–555.21. Yonkers KA, Kando JC, Cole JO, Blumenthal S. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medication. Am J Psychiatry. 1992; 149:587–595.

Article22. Chamberlain S, Hahn PM, Casson P, Reid RL. Effect of menstrual cycle phase and oral contraceptive use on serum lithium levels after a loading dose of lithium in normal women. Am J Psychiatry. 1990; 147:907–909.

Article23. Cho MM, Ziats NP, Pal D, Utian WH, Gorodeski GI. Estrogen modulates paracellular permeability of human endothelial cells by eNOS- and iNOS-related mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1999; 276:C337–C349. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.2.C337.

Article24. Shi J, Simpkins JW. 17 beta-Estradiol modulation of glucose transporter 1 expression in blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1997; 272:E1016–E1022.

Article25. Rubinow DR, Roy-Byrne P. Premenstrual syndromes: overview from a methodologic perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 1984; 02. 141:163–172.

Article26. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004; 24:Suppl 1. 9–160.27. Smith MJ, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Operationalizing DSM-IV criteria for PMDD: selecting symptomatic and asymptomatic cycles for research. J Psychiatr Res. 2003; 37:75–83.

Article28. Bolea-Alamanac B, Biley SJ, Lovick TA, Scheele D, Valentino R. Female psychopharmacology matters! Towards a sex-specific pharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2018; 32:125–133. DOI: 10.1177/0269881117747578.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Menstruation and Sleep

- Sustainable Rates of Sebum Excretion in Relation to Menstrual Cycle

- The Effect of Hormonal Changes During the Menstrual Cycle on the Brain: Focusing on Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Studies

- Impact of Perfectionism and Testing Anxiety on the Menstrual Cycle during Test Evaluations among High School Girls

- Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Background Parenchymal Enhancement Observed on Breast MRIs in Korean Women