Int J Stem Cells.

2019 Jul;12(2):304-314. 10.15283/ijsc18114.

Effect of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Ischaemic-Reperfused Hearts in Adult Rats with Established Chronic Kidney Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

- 2Department of Biochemistry, Medical Research Center, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. f_abu_zahra@hotmail.com

- KMID: 2465900

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc18114

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

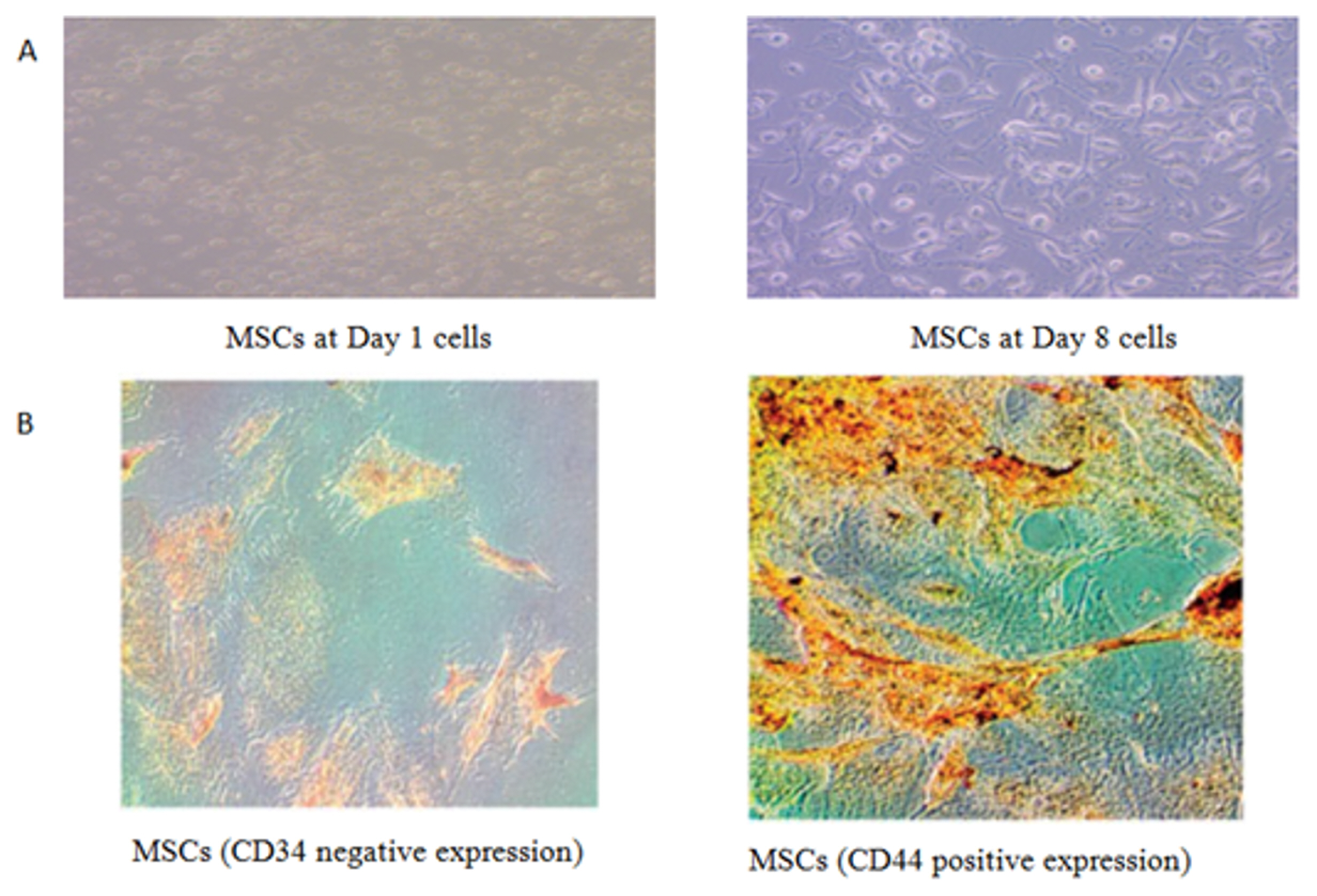

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) are adult multipotent non-haematopoietic stem cells that have regeneration potential. The current study aimed to detect the ability of BM-MSCs to improve kidney and cardiac functions in adult rats with established chronic kidney disease.

METHODS

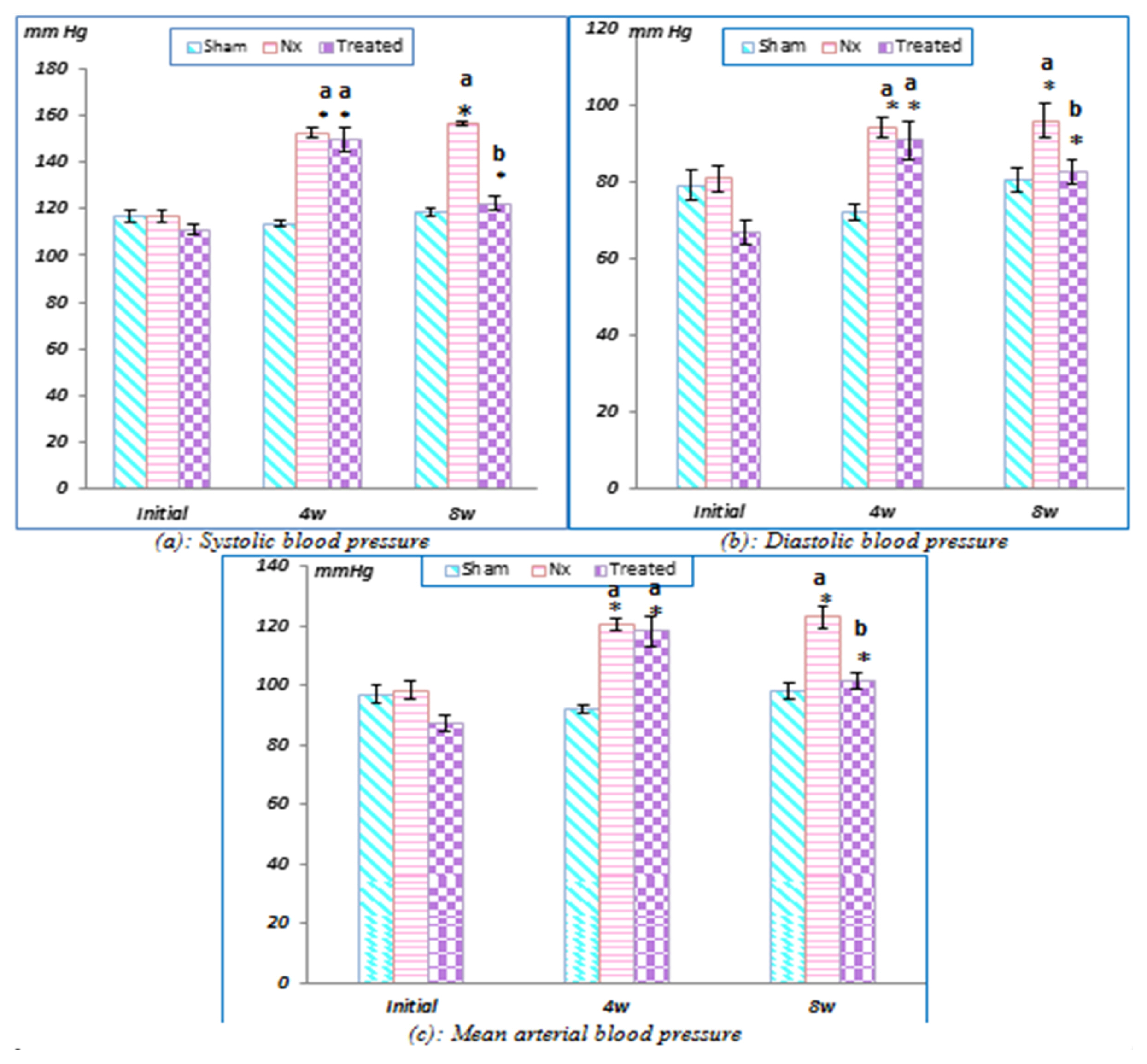

Rats were divided into sham-operated control, untreated sub totally nephrectomised and treated sub totally nephrectomised groups. Body weight, kidney and cardiac tissue weights, plasma creatinine and urea levels and arterial blood pressure were measured. ECG was recorded, and an in vitro isolated heart study was performed.

Results

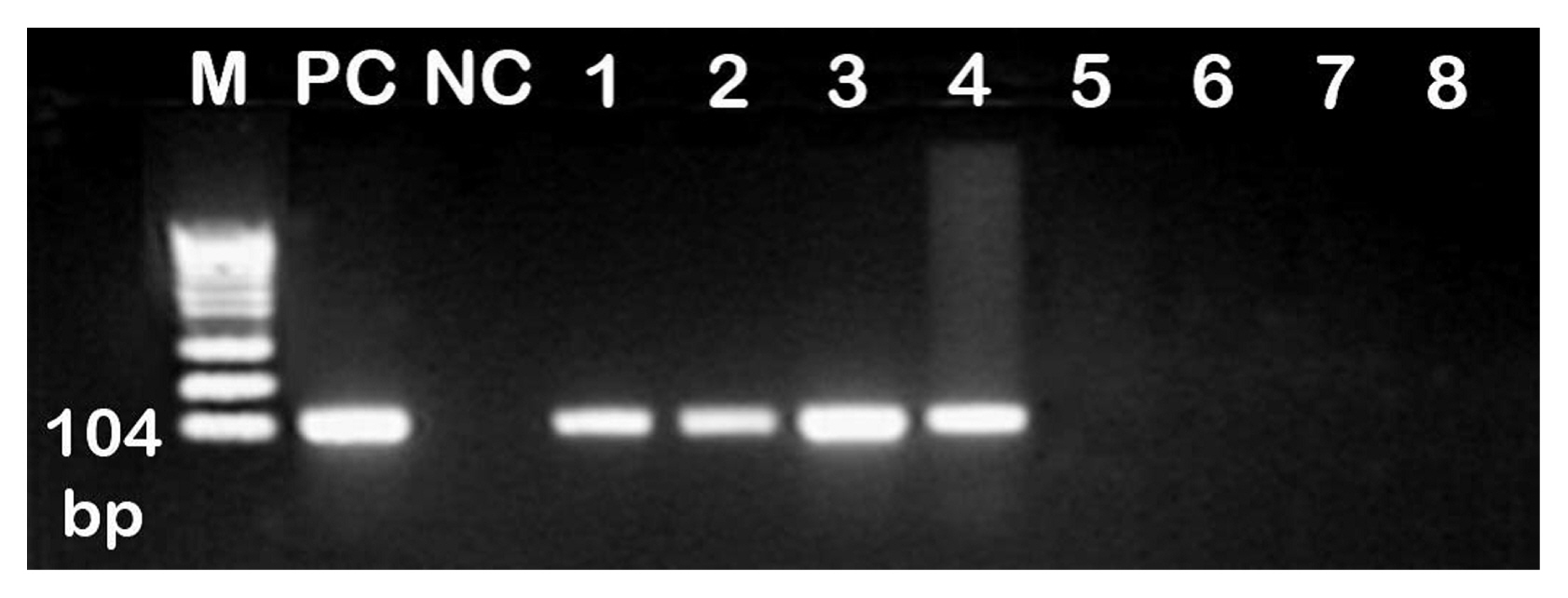

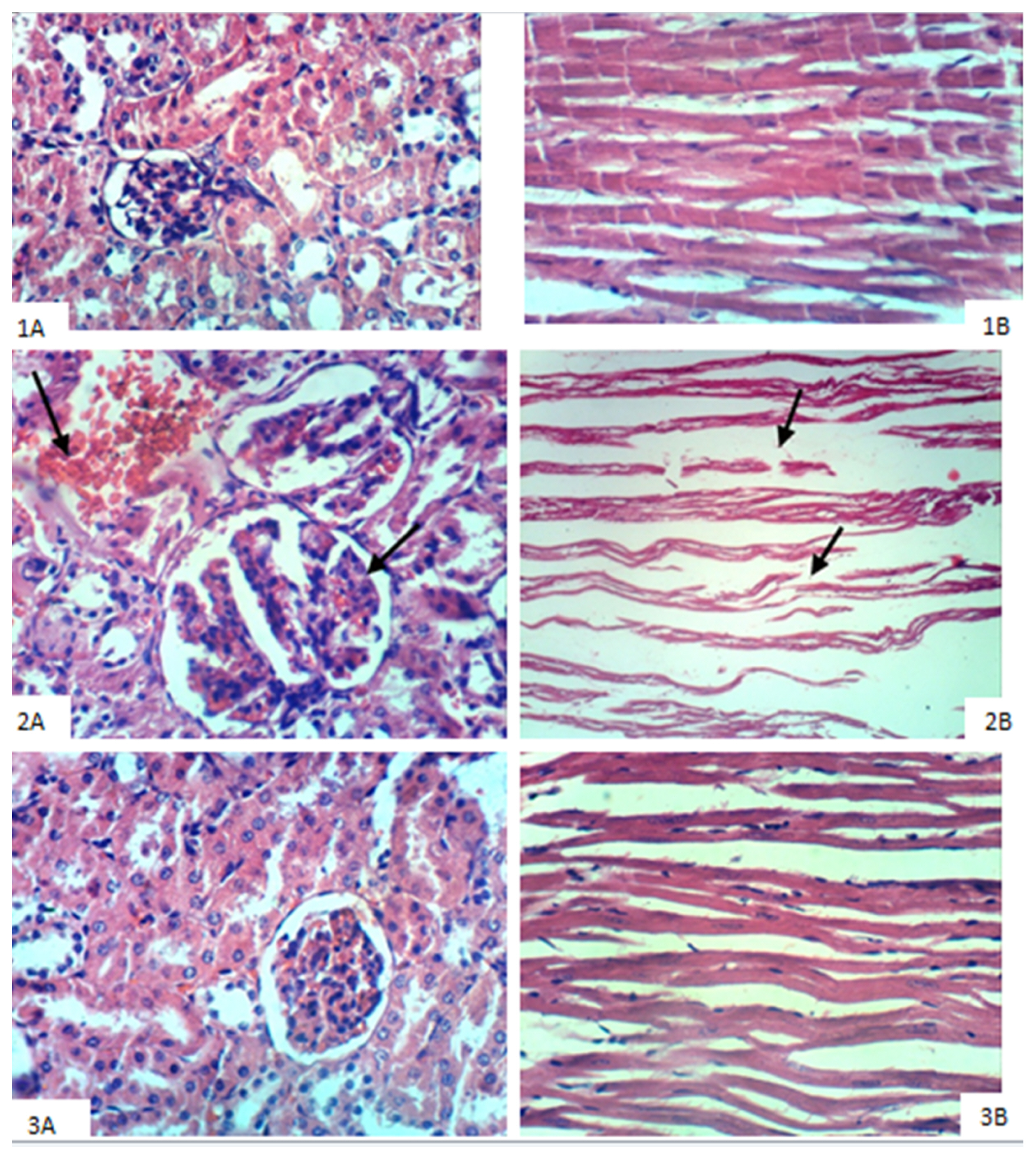

Stem cell treatment decreased the elevated plasma creatinine and urea levels and decreased systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure values. These changes were accompanied by a decrease in glomerular hypertrophy with apparent normal renal parenchyma. Additionally, BM-MSCs shortened Q-To and Q-Tc intervals, all time to peak tension values, the half relaxation value at 30 min of reperfusion and the contraction time at 15 and 30 min of reperfusion. Moreover, stem cell treatment significantly increased the heart rate, QRS voltage, the peak tension at the 15- and 30-min reperfusion time points and the peak tension per left ventricle at the 30-min reperfusion time point compared to the pre-ischaemia baseline. BM-MSCs resolve inter muscular oedema and lead to the re-appearance of normal cardiomyocytes. This improvement occurs with the observations of BM-MSCs in renal and heart tissues.

CONCLUSIONS

BM-MSCs can attenuate chronic kidney disease progression and the associated cardiac electrophysiological and inotropic dysfunction.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adult*

Animals

Arterial Pressure

Body Weight

Creatinine

Electrocardiography

Heart Rate

Heart Ventricles

Heart*

Humans

Hypertrophy

In Vitro Techniques

Kidney

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells*

Myocytes, Cardiac

Nephrectomy

Plasma

Rats*

Regeneration

Relaxation

Renal Insufficiency, Chronic*

Reperfusion

Stem Cells

Urea

Weights and Measures

Creatinine

Urea

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O’Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, Hobbs FD. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0158765. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765. PMID: 27383068. PMCID: PMC4934905.

Article2. Efstratiadis G, Divani M, Katsioulis E, Vergoulas G. Renal fibrosis. Hippokratia. 2009; 13:224–229. PMID: 20011086. PMCID: PMC2776335.3. Granata S, Zaza G, Simone S, Villani G, Latorre D, Pontrelli P, Carella M, Schena FP, Grandaliano G, Pertosa G. Mitochondrial dysregulation and oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Genomics. 2009; 10:388. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-388. PMID: 19698090. PMCID: PMC2737002.

Article4. Briet M, Burns KD. Chronic kidney disease and vascular remodelling: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012; 123:399–416. DOI: 10.1042/CS20120074. PMID: 22671427.

Article5. Roemeling-van Rhijn M, Reinders ME, de Klein A, Douben H, Korevaar SS, Mensah FK, Dor FJ, IJzermans JN, Betjes MG, Baan CC, Weimar W, Hoogduijn MJ. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue are not affected by renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012; 82:748–758. DOI: 10.1038/ki.2012.187. PMID: 22695328.

Article6. Kunter U, Rong S, Moeller MJ, Floege J. Mesenchymal stem cells as a therapeutic approach to glomerular diseases: benefits and risks. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2011; 1:68–73. DOI: 10.1038/kisup.2011.16. PMID: 25018904. PMCID: PMC4089694.

Article7. Murphy MB, Moncivais K, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine. Exp Mol Med. 2013; 45:e54. DOI: 10.1038/emm.2013.94. PMID: 24232253. PMCID: PMC3849579.

Article8. Morigi M, Introna M, Imberti B, Corna D, Abbate M, Rota C, Rottoli D, Benigni A, Perico N, Zoja C, Rambaldi A, Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells accelerate recovery of acute renal injury and prolong survival in mice. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:2075–2082. DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0795. PMID: 18499895.

Article9. Villanueva S, Ewertz E, Carrión F, Tapia A, Vergara C, Céspedes C, Sáez PJ, Luz P, Irarrázabal C, Carreño JE, Figueroa F, Vio CP. Mesenchymal stem cell injection ameliorates chronic renal failure in a rat model. Clin Sci (Lond). 2011; 121:489–499. DOI: 10.1042/CS20110108. PMID: 21675962.

Article10. Gheisari Y, Ahmadbeigi N, Naderi M, Nassiri SM, Nadri S, Soleimani M. Stem cell-conditioned medium does not protect against kidney failure. Cell Biol Int. 2011; 35:209–213. DOI: 10.1042/CBI20100183. PMID: 20950276.

Article11. Huuskes BM, Wise AF, Cox AJ, Lim EX, Payne NL, Kelly DJ, Samuel CS, Ricardo SD. Combination therapy of mesenchymal stem cells and serelaxin effectively attenuates renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. FASEB J. 2015; 29:540–553. DOI: 10.1096/fj.14-254789. PMID: 25395452.

Article12. Yuen DA, Connelly KA, Advani A, Liao C, Kuliszewski MA, Trogadis J, Thai K, Advani SL, Zhang Y, Kelly DJ, Leong-Poi H, Keating A, Marsden PA, Stewart DJ, Gilbert RE. Culture-modified bone marrow cells attenuate cardiac and renal injury in a chronic kidney disease rat model via a novel antifibrotic mechanism. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e9543. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009543. PMID: 20209052. PMCID: PMC2832011.

Article13. Addis T, Lew W. The restoration of lost organ tissue : the rate and degree of restoration. J Exp Med. 1940; 71:325–333. DOI: 10.1084/jem.71.3.325. PMID: 19870966. PMCID: PMC2134995.14. McFarlin K, Gao X, Liu YB, Dulchavsky DS, Kwon D, Arbab AS, Bansal M, Li Y, Chopp M, Dulchavsky SA, Gautam SC. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells accelerate wound healing in the rat. Wound Repair Regen. 2006; 14:471–478. DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00153.x. PMID: 16939576.

Article15. Li H, Fu X, Ouyang Y, Cai C, Wang J, Sun T. Adult bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells contribute to wound healing of skin appendages. Cell Tissue Res. 2006; 326:725–736. DOI: 10.1007/s00441-006-0270-9. PMID: 16906419.

Article16. Goldschlager N, Goldman MJ. Electrocardiography: essentials of interpretation. Los Altos, California: Lang Medical Publications;1984. p. 13–18.17. Ayobe MH, Tarazi RC. Beta-Receptors and contractile reserve in left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension. 1983; 5:I192–I197. DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.5.2_Pt_2.I192. PMID: 6298104.

Article18. Abdel Aziz MT, Atta HM, Mahfouz S, Fouad HH, Roshdy NK, Ahmed HH, Rashed LA, Sabry D, Hassouna AA, Hasan NM. Therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on experimental liver fibrosis. Clin Biochem. 2007; 40:893–899. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.04.017. PMID: 17543295.

Article19. Tietz NW. Clinical guide to laboratory tests. 3rd ed.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;1995.20. Young DS. Effects of drugs on clinical laboratory tests. 4th ed.Washington: AACC Press;1995.21. Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical methods in medical research. 2nd ed.London: Blackwell Scientific Publications;1987.22. Nagy K, Nagaraju SP, Rhee CM, Mathe Z, Molnar MZ. Adipocytokines in renal transplant recipients. Clin Kidney J. 2016; 9:359–373. DOI: 10.1093/ckj/sfv156. PMID: 27274819. PMCID: PMC4886901.

Article23. Garibotto G, Russo R, Sofia A, Ferone D, Fiorini F, Cappelli V, Tarroni A, Gandolfo MT, Vigo E, Valli A, Arvigo M, Verzola D, Ravera G, Minuto F. Effects of uremia and inflammation on growth hormone resistance in patients with chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2008; 74:937–945. DOI: 10.1038/ki.2008.345. PMID: 18633341.

Article24. Yisireyili M, Shimizu H, Saito S, Enomoto A, Nishijima F, Niwa T. Indoxyl sulfate promotes cardiac fibrosis with enhanced oxidative stress in hypertensive rats. Life Sci. 2013; 92:1180–1185. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.05.008. PMID: 23702423.

Article25. Choi DH, Ahn SH, Jung SW, Lee YM, Kim HJ, Lee MS, Baek SH, Song JH. Clinical characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease associated with marked bradycardia. Korean J Nephrol. 2004; 23:256–262.26. Madias JE. Low QRS voltage and its causes. J Electrocardiol. 2008; 41:498–500. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.06.021. PMID: 18804788.

Article27. El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiol J. 2011; 18:233–245. PMID: 21660912.28. Tang WH, Wang CP, Chung FM, Huang LL, Yu TH, Hung WC, Lu LF, Chen PY, Luo CH, Lee KT, Lee YJ, Lai WT. Uremic retention solute indoxyl sulfate level is associated with prolonged QTc interval in early CKD patients. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0119545. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119545. PMID: 25893644. PMCID: PMC4403985.

Article29. Turer AT, Hill JA. Pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2010; 106:360–368. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.032. PMID: 20643246. PMCID: PMC2957093.

Article30. Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012; 298:229–317. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00006-7. PMID: 22878108. PMCID: PMC3904795.

Article31. Schwarz U, Buzello M, Ritz E, Stein G, Raabe G, Wiest G, Mall G, Amann K. Morphology of coronary atherosclerotic lesions in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000; 15:218–223. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/15.2.218. PMID: 10648668.

Article32. Cannavo A, Liccardo D, Koch WJ. Targeting cardiac β -adrenergic signaling via GRK2 inhibition for heart failure therapy. Front Physiol. 2013; 4:264. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00264. PMID: 24133451. PMCID: PMC3783981.33. Bombardini T, Zoppè M, Ciampi Q, Cortigiani L, Agricola E, Salvadori S, Loni T, Pratali L, Picano E. Myocardial contractility in the stress echo lab: from pathophysiological toy to clinical tool. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2013; 11:41. DOI: 10.1186/1476-7120-11-41. PMID: 24246005. PMCID: PMC3875530.

Article34. Abdel Aziz MT, Wassef MA, Ahmed HH, Rashed L, Mahfouz S, Aly MI, Hussein RE, Abdelaziz M. The role of bone marrow derived-mesenchymal stem cells in attenuation of kidney function in rats with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014; 6:34. DOI: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-34. PMID: 24606996. PMCID: PMC4007638.

Article35. Baglio SR, Pegtel DM, Baldini N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front Physiol. 2012; 3:359. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00359. PMID: 22973239. PMCID: PMC3434369.

Article36. Quevedo HC, Hatzistergos KE, Oskouei BN, Feigenbaum GS, Rodriguez JE, Valdes D, Pattany PM, Zambrano JP, Hu Q, McNiece I, Heldman AW, Hare JM. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells restore cardiac function in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy via trilineage differentiating capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:14022–14027. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0903201106. PMID: 19666564. PMCID: PMC2729013.

Article37. Ly HQ, Nattel S. Stem cells are not proarrhythmic: letting the genie out of the bottle. Circulation. 2009; 119:1824–1831. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812701. PMID: 19349335.

Article38. Ayatollahi M, Hesami Z, Jamshidzadeh A, Gramizadeh B. Antioxidant effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative damage in rat livers. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2014; 5:166–173. PMID: 25426285. PMCID: PMC4243048.39. Nargesi AA, Lerman LO, Eirin A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for renal repair. Curr Gene Ther. 2017; 17:29–42. DOI: 10.2174/1566523217666170412110724. PMID: 28403795. PMCID: PMC5628022.

Article40. Papazova DA, Oosterhuis NR, Gremmels H, van Koppen A, Joles JA, Verhaar MC. Cell-based therapies for experimental chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Model Mech. 2015; 8:281–293. DOI: 10.1242/dmm.017699. PMID: 25633980. PMCID: PMC4348565.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Concise Review: Differentiation of Human Adult Stem Cells Into Hepatocyte-like Cells In vitro

- Clinical Safety and Efficacy of Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Sensorineural Hearing Loss Patients

- Neural Differentiation of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Applicability for Inner Ear Therapy

- Stem Cells and Niemann Pick Disease

- Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine