J Pathol Transl Med.

2019 Jul;53(4):225-235. 10.4132/jptm.2019.03.12.

CpG Island Methylation in Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp of the Colorectum: Implications for Differential Diagnosis of Molecularly High-Risk Lesions among Non-dysplastic Sessile Serrated Adenomas/Polyps

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pathology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. junghokim@snuh.org

- 2Laboratory of Epigenetics, Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2454602

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2019.03.12

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Although colorectal sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) with morphologic dysplasia are regarded as definite high-risk premalignant lesions, no reliable grading or risk-stratifying system exists for non-dysplastic SSA/Ps. The accumulation of CpG island methylation is a molecular hallmark of progression of SSA/Ps. Thus, we decided to classify non-dysplastic SSA/Ps into risk subgroups based on the extent of CpG island methylation.

METHODS

The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) status of 132 non-dysplastic SSA/Ps was determined using eight CIMP-specific promoter markers. SSA/Ps with CIMP-high and/or MLH1 promoter methylation were regarded as a high-risk subgroup.

RESULTS

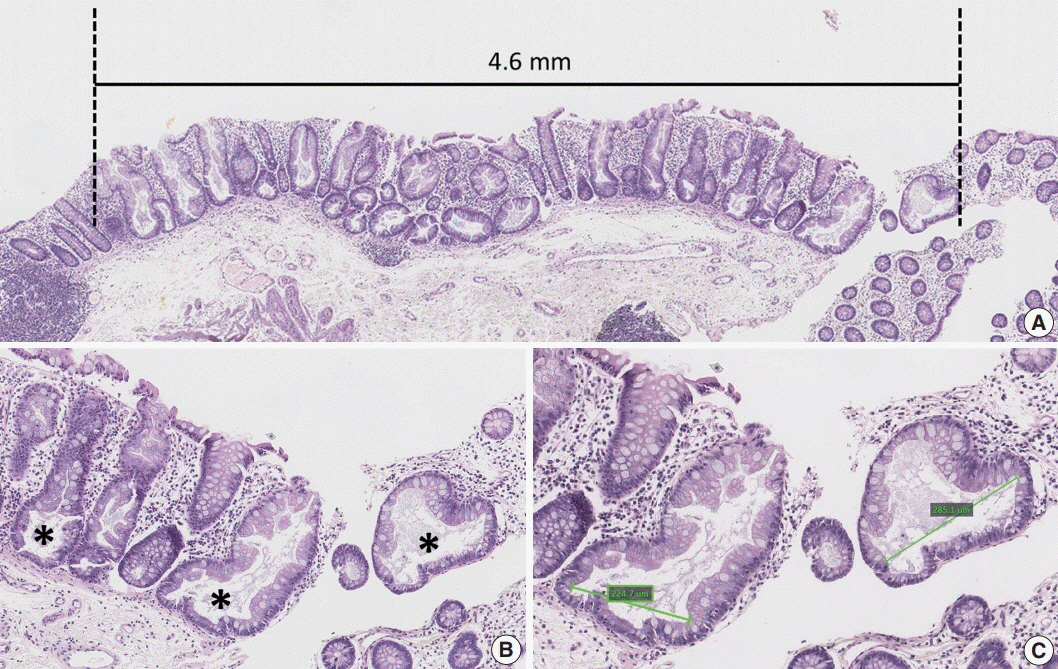

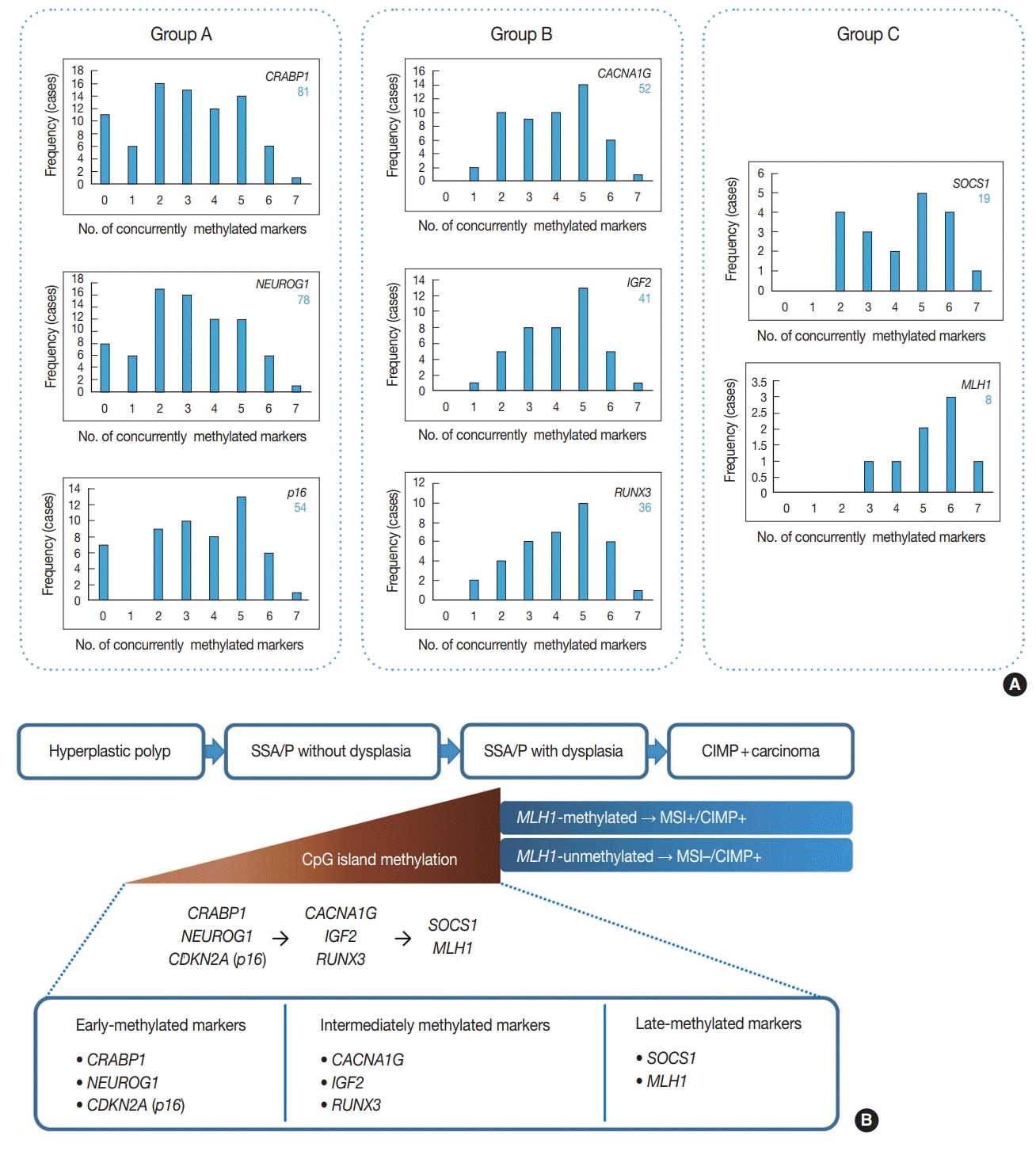

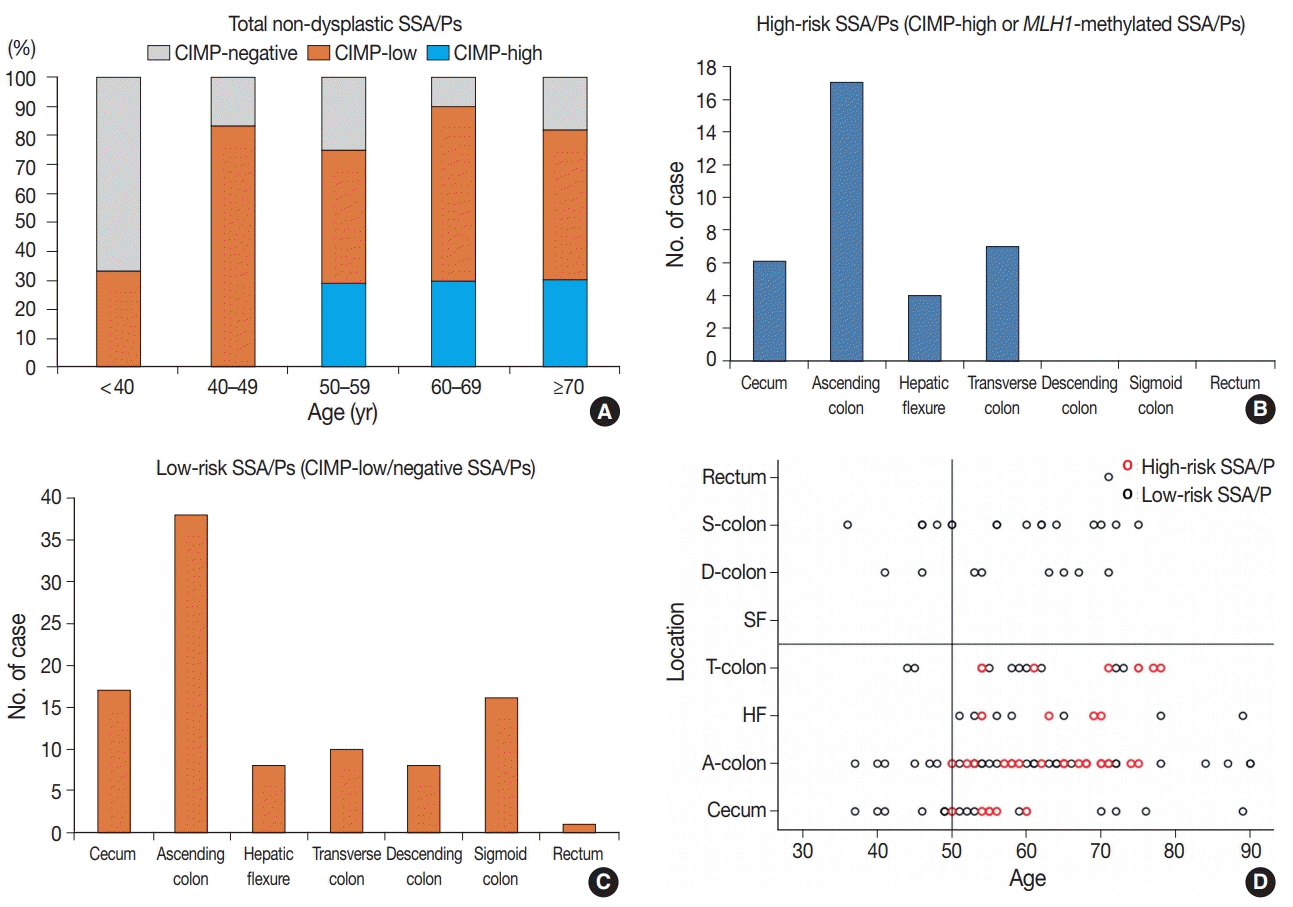

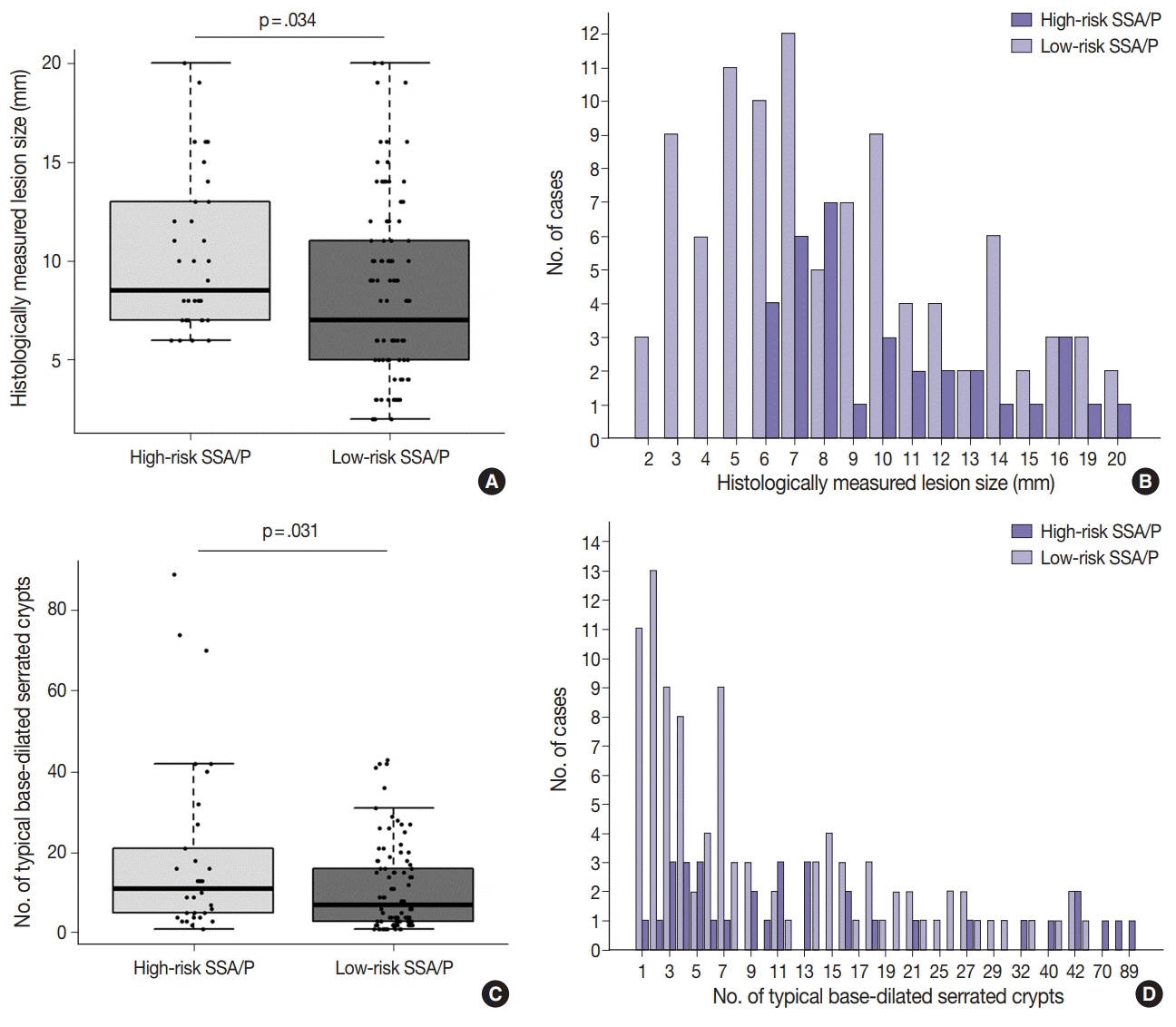

Based on the CIMP analysis results, methylation frequency of each CIMP marker suggested a sequential pattern of CpG island methylation during progression of SSA/P, indicating MLH1 as a late-methylated marker. Among the 132 non-dysplastic SSA/Ps, 34 (26%) were determined to be high-risk lesions (33 CIMP-high and 8 MLH1-methylated cases; seven cases overlapped). All 34 high-risk SSA/Ps were located exclusively in the proximal colon (100%, p = .001) and were significantly associated with older age (≥ 50 years, 100%; p = .003) and a larger histologically measured lesion size (> 5 mm, 100%; p = .004). In addition, the high-risk SSA/Ps were characterized by a relatively higher number of typical base-dilated serrated crypts.

CONCLUSIONS

Both CIMP-high and MLH1 methylation are late-step molecular events during progression of SSA/Ps and rarely occur in SSA/Ps of young patients. Comprehensive consideration of age (≥ 50), location (proximal colon), and histologic size (> 5 mm) may be important for the prediction of high-risk lesions among non-dysplastic SSA/Ps.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Evolving pathologic concepts of serrated lesions of the colorectum

Jung Ho Kim, Gyeong Hoon Kang

J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54(4):276-289. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2020.04.15.

Reference

-

1. Bae JM, Kim JH, Kang GH. Molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and their clinicopathologic features, with an emphasis on the serrated neoplasia pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016; 140:406–12.

Article2. Lochhead P, Chan AT, Giovannucci E, et al. Progress and opportunities in molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal premalignant lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 109:1205–14.

Article3. Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011; 42:1–10.

Article4. Batts KP. The pathology of serrated colorectal neoplasia: practical answers for common questions. Mod Pathol. 2015; 28 Suppl 1:S80–7.

Article5. Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer;2010.6. Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1315–29.

Article7. IJspeert JE, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasiarole in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 12:401–9.

Article8. Kim JH, Bae JM, Cho NY, Kang GH. Distinct features between MLH1-methylated and unmethylated colorectal carcinomas with the CpG island methylator phenotype: implications in the serrated neoplasia pathway. Oncotarget. 2016; 7:14095–111.

Article9. Bateman AC, Shepherd NA. UK guidance for the pathological reporting of serrated lesions of the colorectum. J Clin Pathol. 2015; 68:585–91.

Article10. Crockett SD, Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA. Sessile serrated adenomas: an evidence-based guide to management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 13:11–26. e1.

Article11. Parker HR, Orjuela S, Martinho Oliveira A, et al. The proto CpG island methylator phenotype of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Epigenetics. 2018; 13:1088–105.

Article12. Sakai E, Nakajima A, Kaneda A. Accumulation of aberrant DNA methylation during colorectal cancer development. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:978–87.

Article13. Bae JM, Kim JH, Oh HJ, et al. Downregulation of acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 is a metabolic hallmark of tumor progression and aggressiveness in colorectal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2017; 30:267–77.

Article14. Oh HJ, Kim JH, Bae JM, Kim HJ, Cho NY, Kang GH. Prognostic impact of Fusobacterium nucleatum depends on combined tumor location and microsatellite instability status in stage II/III colorectal cancers treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. J Pathol Transl Med. 2019; 53:40–9.15. Ogino S, Cantor M, Kawasaki T, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) of colorectal cancer is best characterised by quantitative DNA methylation analysis and prospective cohort studies. Gut. 2006; 55:1000–6.

Article16. Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Kraft P, Loda M, Fuchs CS. Evaluation of markers for CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer by a large population-based sample. J Mol Diagn. 2007; 9:305–14.

Article17. Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, et al. Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large population-based sample. PLoS One. 2008; 3:e3698.

Article18. Kim JH, Shin SH, Kwon HJ, Cho NY, Kang GH. Prognostic implications of CpG island hypermethylator phenotype in colorectal cancers. Virchows Arch. 2009; 455:485–94.

Article19. Wen X, Jeong S, Kim Y, et al. Improved results of LINE-1 methylation analysis in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues with the application of a heating step during the DNA extraction process. Clin Epigenetics. 2017; 9:1.

Article20. Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut. 2017; 66:97–106.

Article21. Burgess NG, Tutticci NJ, Pellise M, Bourke MJ. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with cytologic dysplasia: a triple threat for interval cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 80:307–10.

Article22. Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006; 38:787–93.

Article23. Liu C, Bettington ML, Walker NI, et al. CpG island methylation in sessile serrated adenomas increases with age, indicating lower risk of malignancy in young patients. Gastroenterology. 2018; 155:1362–5. e2.

Article24. Bettington M, Brown I, Rosty C, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas in young patients may have limited risk of malignant progression. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019; 53:e113–6.

Article25. He EY, Wyld L, Sloane MA, Canfell K, Ward RL. The molecular characteristics of colonic neoplasms in serrated polyposis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016; 2:127–37.

Article26. Edelstein DL, Axilbund JE, Hylind LM, et al. Serrated polyposis: rapid and relentless development of colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2013; 62:404–8.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Evolving pathologic concepts of serrated lesions of the colorectum

- Serrated neoplasia pathway as an alternative route of colorectal cancer carcinogenesis

- Sessile Serrated Adenoma with High-grade Dysplasia

- Screening Relevance of Sessile Serrated Polyps

- Characteristics and outcomes of endoscopically resected colorectal cancers that arose from sessile serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas