Korean Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-induced Osteoporosis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea.

- 3Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea.

- 4Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Wonkwang University Sanbon Hospital, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Gunpo, Korea.

- 6Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Bucheon, Korea.

- 7Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Department of Rheumatology, Chonnam National University Medical School and Hospital, Gwangju, Korea.

- 9Division of Healthcare Technology Assessment Research, National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, Seoul, Korea.

- 10Department of Rheumatology, Hanyang University Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Seoul, Korea. swkimmd@snu.ac.kr

- 11Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. swkimmd@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2427985

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2018.25.4.195

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

To develop guidelines and recommendations to prevent and treat glucocorticoid (GC)-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) in Korea.

METHODS

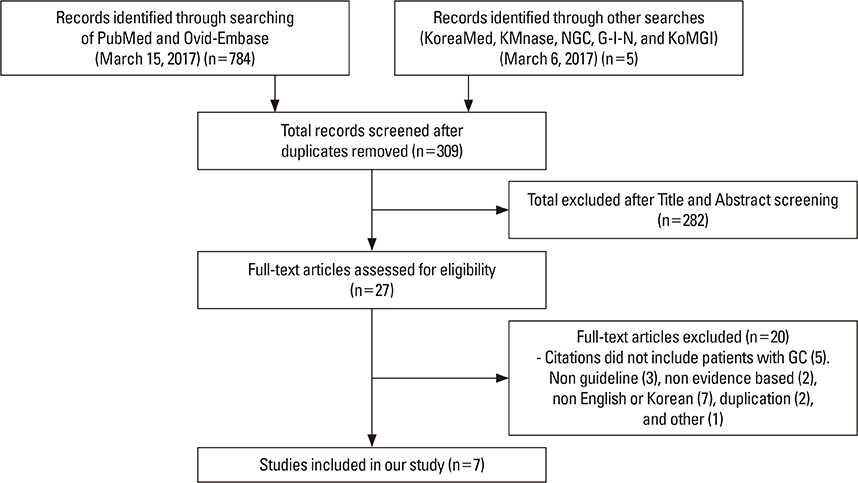

The Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the Korean College of Rheumatology have developed this guideline based on Guidance for the Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines ver. 1.0 established by the National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency. This guideline was developed by adapting previously published guidelines, and a systematic review and quality assessment were performed.

RESULTS

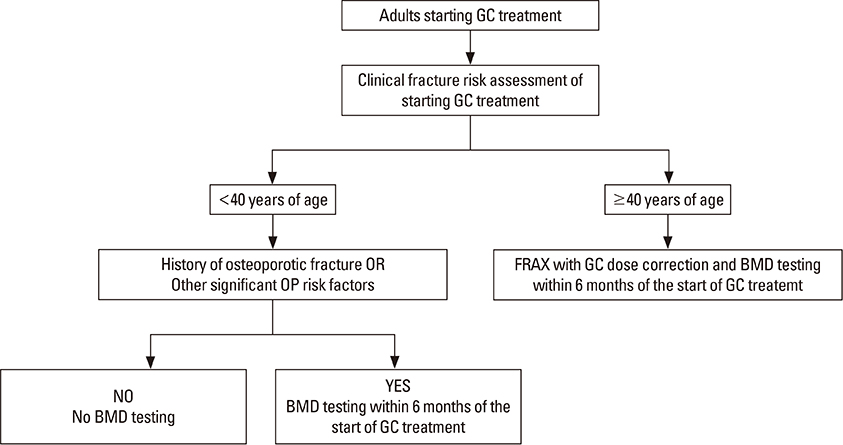

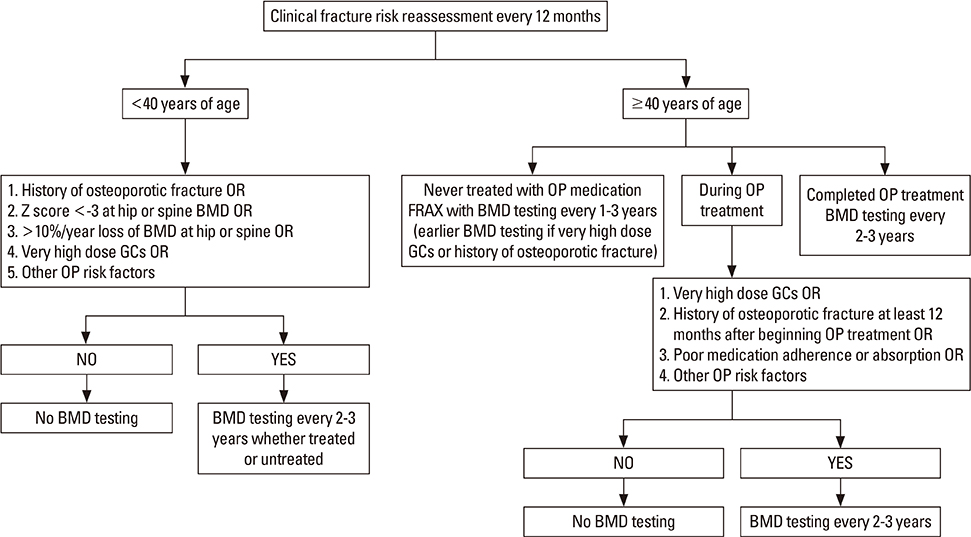

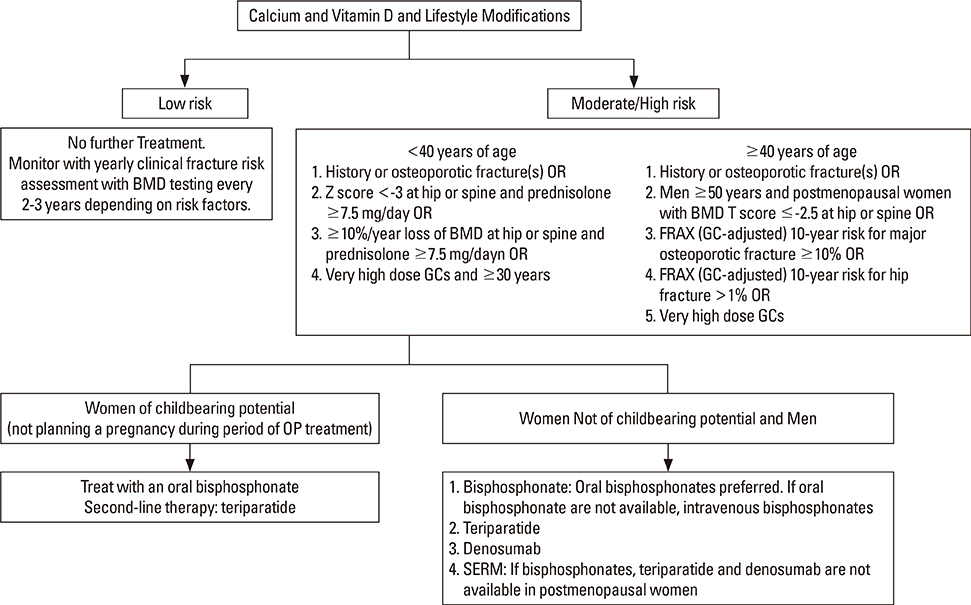

This guideline applies to adults aged ≥19 years who are using or plan to use GCs. It does not include children and adolescents. An initial assessment of fracture risk should be performed within 6 months of initial GC use. Fracture risk should be estimated using the fracture-risk assessment tool (FRAX) after adjustments for GC dose, history of osteoporotic fractures, and bone mineral density (BMD) results. All patients administered with prednisolone or an equivalent medication at a dose ≥2.5 mg/day for ≥3 months are recommended to use adequate calcium and vitamin D during treatment. Patients showing a moderate-to-high fracture risk should be treated with additional medication for osteoporosis. All patients continuing GC therapy should undergo annual BMD testing, vertebral X-ray, and fracture risk assessment using FRAX. When treatment failure is suspected, switching to another drug should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

This guideline is intended to guide clinicians in the prevention and treatment of GIOP.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Fracture Risk and Its Prevention Patterns in Korean Patients with Polymyalgia Rheumatica: a Retrospective Cohort Study

Bora Nam, Yoon-Kyoung Sung, Chan-Bum Choi, Tae-Hwan Kim, Jae-Bum Jun, Sang-Cheol Bae, Dae-Hyun Yoo, Soo-Kyung Cho

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(41):e263. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e263.The Korean College of Rheumatology: 40 Years of Public Health Influence

Jisoo Lee, Yoon-Kyoung Sung, Myeung-Su Lee, Han Joo Baek

J Rheum Dis. 2022;29(2):75-78. doi: 10.4078/jrd.2022.29.2.75.Update on Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

Soo-Kyung Cho, Yoon-Kyoung Sung

Endocrinol Metab. 2021;36(3):536-543. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1021.Treatment of Autoimmune Hepatitis

Ja Kyung Kim

Korean J Gastroenterol. 2023;81(2):72-85. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2023.011.

Reference

-

1. Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, et al. Low dose long-term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of serious adverse events. Am J Med. 1994; 96:115–123.

Article2. Lane NE, Lukert B. The science and therapy of glucocorticoid-induced bone loss. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1998; 27:465–483.

Article3. Van Staa TP, Laan RF, Barton IP, et al. Bone density threshold and other predictors of vertebral fracture in patients receiving oral glucocorticoid therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 48:3224–3229.

Article4. Steinbuch M, Youket TE, Cohen S. Oral glucocorticoid use is associated with an increased risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004; 15:323–328.

Article5. Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone. 2006; 39:253–259.

Article6. Feldstein AC, Elmer PJ, Nichols GA, et al. Practice patterns in patients at risk for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2005; 16:2168–2174.

Article7. Salerno A, Hermann R. Efficacy and safety of steroid use for postoperative pain relief. Update and review of the medical literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006; 88:1361–1372.8. Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Monitoring of patients on long-term glucocorticoid therapy: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e647.9. Van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, et al. Use of oral corticosteroids in the United Kingdom. QJM. 2000; 93:105–111.

Article10. Van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. The epidemiology of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2002; 13:777–787.

Article11. LoCascio V, Bonucci E, Imbimbo B, et al. Bone loss in response to long-term glucocorticoid therapy. Bone Miner. 1990; 8:39–51.

Article12. Kim D, Cho SK, Park B, et al. Glucocorticoids are associated with an increased risk for vertebral fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018; 45:612–620.

Article13. Weinstein RS. True strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2000; 15:621–625.

Article14. Leslie WD. The importance of spectrum bias on bone density monitoring in clinical practice. Bone. 2006; 39:361–368.

Article15. Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:2250–2261.

Article16. Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, et al. 2017 American college of rheumatology guideline for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017; 69:1095–1110.

Article17. Van Staa TP, Geusens P, Pols HA, et al. A simple score for estimating the long-term risk of fracture in patients using oral glucocorticoids. QJM. 2005; 98:191–198.

Article18. Hall GM, Spector TD, Griffin AJ, et al. The effect of rheumatoid arthritis and steroid therapy on bone density in postmenopausal women. Arthritis Rheum. 1993; 36:1510–1516.

Article19. Laan RF, van Riel PL, van de Putte LB, et al. Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 119:963–968.

Article20. Kim SY, Jee SM, Lee SJ, et al. Guidance for development of clinical practice guidelines. ver 1.0. Seoul: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency;2011.21. Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK, et al. American college of rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010; 62:1515–1526.

Article22. Lekamwasam S, Adachi JD, Agnusdei D, et al. A framework for the development of guidelines for the management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012; 23:2257–2276.

Article23. Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010; 182:1864–1873.

Article24. Briot K, Cortet B, Roux C, et al. 2014 update of recommendations on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014; 81:493–501.

Article25. Pereira RM, Carvalho JF, Paula AP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2012; 52:580–593.26. Suzuki Y, Nawata H, Soen S, et al. Guidelines on the management and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research: 2014 update. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014; 32:337–350.

Article27. Rossini M, Adami S, Bertoldo F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of osteoporosis. Reumatismo. 2016; 68:1–39.

Article28. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010; 63:1308–1311.

Article29. Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos. 2017; 12:43.

Article30. Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. Guidance for the adjustment of FRAX according to the dose of glucocorticoids. Osteoporos Int. 2011; 22:809–816.

Article31. Kaji H, Yamauchi M, Chihara K, et al. Glucocorticoid excess affects cortical bone geometry in premenopausal, but not postmenopausal, women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008; 82:182–190.

Article32. Fassio A, Idolazzi L, Jaber MA, et al. The negative bone effects of the disease and of chronic corticosteroid treatment in premenopausal women affected by rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo. 2016; 68:65–71.

Article33. Canalis E, Mazziotti G, Giustina A, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2007; 18:1319–1328.

Article34. Sambrook P, Birmingham J, Kelly P, et al. Prevention of corticosteroid osteoporosis. A comparison of calcium, calcitriol, and calcitonin. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:1747–1752.

Article35. Boutsen Y, Jamart J, Esselinckx W, et al. Primary prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis with intravenous pamidronate and calcium: a prospective controlled 1-year study comparing a single infusion, an infusion given once every 3 months, and calcium alone. J Bone Miner Res. 2001; 16:104–112.

Article36. Adachi JD, Bensen WG, Bianchi F, et al. Vitamin D and calcium in the prevention of corticosteroid induced osteoporosis: a 3 year followup. J Rheumatol. 1996; 23:995–1000.37. Buckley LM, Leib ES, Cartularo KS, et al. Calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation prevents bone loss in the spine secondary to low-dose corticosteroids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 125:961–968.

Article38. Braun JJ, Birkenhäger-Frenkel DH, Rietveld AH, et al. Influence of 1 alpha-(OH)D3 administration on bone and bone mineral metabolism in patients on chronic glucocorticoid treatment; a double blind controlled study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1983; 19:265–273.

Article39. Reginster JY, Kuntz D, Verdickt W, et al. Prophylactic use of alfacalcidol in corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1999; 9:75–81.

Article40. Okada Y, Nawata M, Nakayamada S, et al. Alendronate protects premenopausal women from bone loss and fracture associated with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. J Rheumatol. 2008; 35:2249–2254.

Article41. Saag KG, Emkey R, Schnitzer TJ, et al. Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis Intervention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:292–299.

Article42. Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD, et al. Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2001; 44:202–211.

Article43. Lems WF, Lodder MC, Lips P, et al. Positive effect of alendronate on bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on chronic treatment with low-dose prednisone: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2006; 17:716–723.

Article44. Stoch SA, Saag KG, Greenwald M, et al. Once-weekly oral alendronate 70 mg in patients with glucocorticoid-induced bone loss: a 12-month randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2009; 36:1705–1714.

Article45. Tee SI, Yosipovitch G, Chan YC, et al. Prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in immunobullous diseases with alendronate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:307–314.

Article46. Wallach S, Cohen S, Reid DM, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on bone density and vertebral fracture in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000; 67:277–285.

Article47. Yamada S, Takagi H, Tsuchiya H, et al. Comparative studies on effect of risedronate and alfacalcidol against glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritic patients. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2007; 127:1491–1496.

Article48. Cohen S, Levy RM, Keller M, et al. Risedronate therapy prevents corticosteroid-induced bone loss: a twelve-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999; 42:2309–2318.

Article49. Reid DM, Devogelaer JP, Saag K, et al. Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 373:1253–1263.

Article50. Langdahl BL, Marin F, Shane E, et al. Teriparatide versus alendronate for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: an analysis by gender and menopausal status. Osteoporos Int. 2009; 20:2095–2104.

Article51. Saag KG, Wagman RB, Geusens P, et al. Denosumab versus risedronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, double-dummy, non-inferiority study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018; 6:445–454.

Article52. Candelas G, Martinez-Lopez JA, Rosario MP, et al. Calcium supplementation and kidney stone risk in osteoporosis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012; 30:954–961.53. Lewis JR, Radavelli-Bagatini S, Rejnmark L, et al. The effects of calcium supplementation on verified coronary heart disease hospitalization and death in postmenopausal women: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2015; 30:165–175.

Article54. de Nijs RN, Jacobs JW, Lems WF, et al. Alendronate or alfacalcidol in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:675–684.

Article55. Yilmaz L, Ozoran K, Gündüz OH, et al. Alendronate in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate and glucocorticoids. Rheumatol Int. 2001; 20:65–69.

Article56. Eastell R, Devogelaer JP, Peel NF, et al. Prevention of bone loss with risedronate in glucocorticoid-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. Osteoporos Int. 2000; 11:331–337.

Article57. Reid DM, Adami S, Devogelaer JP, et al. Risedronate increases bone density and reduces vertebral fracture risk within one year in men on corticosteroid therapy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001; 69:242–247.

Article58. Reid DM, Hughes RA, Laan RF, et al. Efficacy and safety of daily risedronate in the treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in men and women: a randomized trial. European Corticosteroid-Induced Osteoporosis Treatment Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000; 15:1006–1013.

Article59. Hakala M, Kröger H, Valleala H, et al. Once-monthly oral ibandronate provides significant improvement in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with glucocorticoids for inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012; 41:260–266.

Article60. Sambrook PN, Roux C, Devogelaer JP, et al. Bisphosphonates and glucocorticoid osteoporosis in men: results of a randomized controlled trial comparing zoledronic acid with risedronate. Bone. 2012; 50:289–295.

Article61. Durie BG, Katz M, Crowley J. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:99–102.

Article62. Lazarovici TS, Yahalom R, Taicher S, et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a single-center study of 101 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:850–855.

Article63. Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 144:753–761.

Article64. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Dekkers OM, et al. Atypical fractures and bisphosphonate therapy: a cohort study of patients with femoral fracture with radiographic adjudication of fracture site and features. Bone. 2011; 48:966–971.

Article65. Edwards MH, McCrae FC, Young-Min SA. Alendronate-related femoral diaphysis fracture--what should be done to predict and prevent subsequent fracture of the contralateral side. Osteoporos Int. 2010; 21:701–703.

Article66. Goh SK, Yang KY, Koh JS, et al. Subtrochanteric insufficiency fractures in patients on alendronate therapy: a caution. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007; 89:349–353.67. Ing-Lorenzini K, Desmeules J, Plachta O, et al. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with the long-term use of bisphosphonates: a case series from a Swiss university hospital. Drug Saf. 2009; 32:775–785.

Article68. Kwek EB, Goh SK, Koh JS, et al. An emerging pattern of subtrochanteric stress fractures: a long-term complication of alendronate therapy. Injury. 2008; 39:224–231.

Article69. Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014; 29:1–23.

Article70. Lane NE, Sanchez S, Modin GW, et al. Parathyroid hormone treatment can reverse corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Invest. 1998; 102:1627–1633.

Article71. Saag KG, Zanchetta JR, Devogelaer JP, et al. Effects of teriparatide versus alendronate for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: thirty-six-month results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 60:3346–3355.

Article72. Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, et al. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2028–2039.

Article73. Dore RK, Cohen SB, Lane NE, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving concurrent glucocorticoids or bisphosphonates. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69:872–875.

Article74. Mok CC, Ying KY, To CH, et al. Raloxifene for prevention of glucocorticoid-induced bone loss: a 12-month randomised double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011; 70:778–784.

Article75. Patlas N, Golomb G, Yaffe P, et al. Transplacental effects of bisphosphonates on fetal skeletal ossification and mineralization in rats. Teratology. 1999; 60:68–73.

Article76. Levy S, Fayez I, Taguchi N, et al. Pregnancy outcome following in utero exposure to bisphosphonates. Bone. 2009; 44:428–430.

Article77. Ornoy A, Wajnberg R, Diav-Citrin O. The outcome of pregnancy following pre-pregnancy or early pregnancy alendronate treatment. Reprod Toxicol. 2006; 22:578–579.

Article78. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2016. Endocr Pract. 2016; 22:1–42.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Glucocorticoid-induced Osteoporosis

- Korean Guideline of Glucocorticoid-induced Osteoporosis; Time to Prevent Fracture!

- Understanding of Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

- Update on Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

- Analysis on Management Status of Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis in Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis