J Clin Neurol.

2018 Oct;14(4):523-529. 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.523.

Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs on Language Abilities in Benign Epilepsy of Childhood with Centrotemporal Spikes

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Korea. sunjun@jbnu.ac.kr

- 2Research Institute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Korea.

- KMID: 2424181

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.523

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

This study is to assess the responsiveness of electroencephalography (EEG) abnormalities and their effects on language ability after initiating different types of antiepileptic therapy in children with newly diagnosed benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS).

METHODS

The records of patients newly diagnosed with BECTS (n=120; 69 males) were reviewed retrospectively. The patients were randomly treated with lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate monotherapy, and underwent at least two EEG and standardized language tests. Effects were compared using Pearson's chi-square tests and paired t-tests.

RESULTS

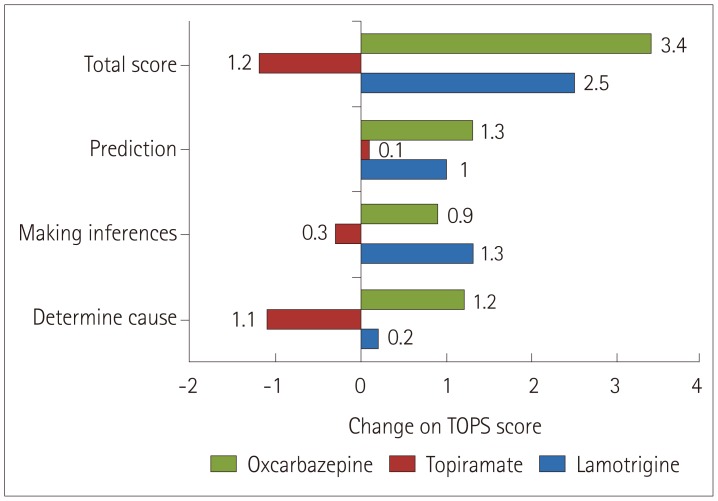

The recurrence rates for seizures in the lamotrigine, topiramate, and oxcarbazepine groups were 19.4%, 21.7%, and 11.4%, respectively, while complete or partial recovery (as indicated by EEG) occurred in 32%, 39%, and 16% of the patients. Patients in the lamotrigine group showed significant improvements in all parameters assessed by the Test of Language Problem Solving Abilities, except for "˜determining cause.' Patients in the oxcarbazepine group also showed improvements, except for "˜making inferences' (p < 0.05). Most linguistic index scores were worse in the topiramate group except for Mean Length of Utterance in Words. Patients in the lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine groups showed significant improvements in the receptive language test (p < 0.05). EEG improvements were not related to language ability.

CONCLUSIONS

The improvements in language and problem-solving performance in children with BECTS were greater for lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine than for topiramate. However, EEG remission did not imply that language function would be improved after the treatments.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Guerrini R, Pellacani S. Benign childhood focal epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2012; 53(Suppl 4):9–18.

Article2. Camfield CS, Camfield PR. Rolandic epilepsy has little effect on adult life 30 years later: a population-based study. Neurology. 2014; 82:1162–1166. PMID: 24562059.

Article3. Hughes JR. Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS): to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 19:197–203. PMID: 20797913.

Article4. Taner Y, Erdoğan-Bakar E, Turanli G, Topçu M. Psychiatric evaluation of children with CSWS (continuous spikes and waves during slow sleep) and BRE (benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes/rolandic epilepsy) compared to children with absence epilepsy and healthy controls. Turk J Pediatr. 2007; 49:397–403. PMID: 18246741.5. Parakh M, Katewa V. A review of the not so benign-benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. J Neurol Neurophysiol. 2015; 6:314.6. Mar'enko LB. “Rolandic” variant of opercular epilepsy. Zh Nevropatol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 1985; 85:1486–1490. PMID: 3934890.7. D'Alessandro P, Piccirilli M, Tiacci C, Ibba A, Maiotti M, Sciarma T, et al. Neuropsychological features of benign partial epilepsy in children. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1990; 11:265–269. PMID: 2117599.8. Danielsson J, Petermann F. Cognitive deficits in children with benign rolandic epilepsy of childhood or rolandic discharges: a study of children between 4 and 7 years of age with and without seizures compared with healthy controls. Epilepsy Behav. 2009; 16:646–651. PMID: 19879197.

Article9. Giordani B, Caveney AF, Laughrin D, Huffman JL, Berent S, Sharma U, et al. Cognition and behavior in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS). Epilepsy Res. 2006; 70:89–94. PMID: 16564678.

Article10. Kavros PM, Clarke T, Strug LJ, Halperin JM, Dorta NJ, Pal DK. Attention impairment in rolandic epilepsy: systematic review. Epilepsia. 2008; 49:1570–1580. PMID: 18410358.

Article11. Smith AB, Kavros PM, Clarke T, Dorta NJ, Tremont G, Pal DK. A neurocognitive endophenotype associated with rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012; 53:705–711. PMID: 22220688.

Article12. Verrotti A, Filippini M, Matricardi S, Agostinelli MF, Gobbi G. Memory impairment and benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spike (BECTS): a growing suspicion. Brain Cogn. 2014; 84:123–131. PMID: 24362071.

Article13. Vannest J, Tenney JR, Gelineau-Morel R, Maloney T, Glauser TA. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Behav. 2015; 45:85–91. PMID: 25775975.

Article14. Freeman JM, Tibbles J, Camfield C, Camfield P. Benign epilepsy of childhood: a speculation and its ramifications. Pediatrics. 1987; 79:864–868. PMID: 3588141.

Article15. Ambrosetto G, Tassinari CA. Antiepileptic drug treatment of benign childhood epilepsy with rolandic spikes: is it necessary? Epilepsia. 1990; 31:802–805. PMID: 2123157.

Article16. Hamada Y, Okuno T, Hattori H, Mikawa H. Indication for anti-epileptic drug treatment of benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes. Brain Dev. 1994; 16:159–161. PMID: 8048708.

Article17. Chahine LM, Mikati MA. Benign pediatric localization-related epilepsies. Epileptic Disord. 2006; 8:243–258. PMID: 17150437.18. Kim SJ, Kim MY, Choi YM, Song MK. Effects of topiramate on language functions in newly diagnosed pediatric epileptic patients. Pediatr Neurol. 2014; 51:324–329. PMID: 24993246.

Article19. Bae SY, Lim SS, Lee JH. Test of Problem Solving. Seoul: Seoul Community Rehabilitation Center;2005.20. Nelson K. Language in Cognitive Development: The Emergence of The Mediated Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;1998.21. Deák GO. Interrelations of language and cognitive development. In : Brooks P, Kampe V, editors. Encyclopedia of Language Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;2014. p. 284–291.22. Turkstra LS, Coelho C, Ylvisaker M. The use of standardized tests for individuals with cognitive-communication disorders. Semin Speech Lang. 2005; 26:215–222. PMID: 16278794.

Article23. Donald M. Précis of origins of the modern mind: three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 1993; 16:737–748.24. Dennett DC. The role of language in intelligence. In : Khalfa J, editor. What is Intelligence? The Darwin College Lectures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;1994.25. Clark EV. How language acquisition builds on cognitive development. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004; 8:472–478. PMID: 15450512.

Article26. Baddeley A. Working memory and language: an overview. J Commun Disord. 2003; 36:189–208. PMID: 12742667.

Article27. Clark MK, Kamhi AG. Language disorders (child language disorders). In : Stone JH, Blouin M, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. Buffalo, NY: Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information & Exchange,;2010.28. Rice ML, Smolik F, Perpich D, Thompson T, Rytting N, Blossom M. Mean length of utterance levels in 6-month intervals for children 3 to 9 years with and without language impairments. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010; 53:333–349. PMID: 20360460.

Article29. Wall KJ, Cumming TB, Copland DA. Determining the association between language and cognitive tests in poststroke aphasia. Front Neurol. 2017; 8:149. PMID: 28529495.

Article30. Lee YW, Sawaki Y. Cognitive diagnosis approaches to language assessment: an overview. Lang Assess Q. 2009; 6:172–189.

Article31. Tan HJ, Singh J, Gupta R, de Goede C. Comparison of antiepileptic drugs, no treatment, or placebo for children with benign epilepsy with centro temporal spikes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 9:CD006779.

Article32. Berroya AG, McIntyre J, Webster R, Lah S, Sabaz M, Lawson J, et al. Speech and language deterioration in benign rolandic epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2004; 19:53–58. PMID: 15032386.

Article33. Kossoff EH, Los JG, Boatman DF. A pilot study transitioning children onto levetiracetam monotherapy to improve language dysfunction associated with benign rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007; 11:514–517. PMID: 17936689.

Article34. Smith AB, Bajomo O, Pal DK. A meta-analysis of literacy and language in children with rolandic epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015; 57:1019–1026. PMID: 26219529.

Article35. Seidel WT, Mitchell WG. Cognitive and behavioral effects of carbamazepine in children: data from benign rolandic epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 1999; 14:716–723. PMID: 10593548.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Children with Centrotemporal Spikes: Clinical and EEG Characteristics

- Cognitive and Behavioral Problems and the Effectiveness of Topiramate Once per Day in the Control of Benign Childhood Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes

- Analysis of Interictal Epileptiform Discharges in the Benign Childhood Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes: Prediction of Seizure Outcome

- Clinical Study of Benign Childhood Epilepsy with Centro-Temporal Spikes

- A Case of a Coincidence of Rolandic and Childhood Absence Epilepsy