J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2018 Sep;61(5):645-652. 10.3340/jkns.2018.0021.

Prospective Multicenter Surveillance Study of Surgical Site Infection after Intracranial Procedures in Korea : A Preliminary Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea. gtyee@gilhospital.com

- KMID: 2420074

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2018.0021

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to investigate the rates, types, and risk factors of surgical site infection (SSI) following intracranial neurosurgical procedures evaluated by a Korean SSI surveillance system.

METHODS

This was a prospective observational study of patients who underwent neurosurgical procedures at 29 hospitals in South Korea from January 2017 to June 2017. The procedures included craniectomy, craniotomy, cranioplasty, burr hole, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

RESULTS

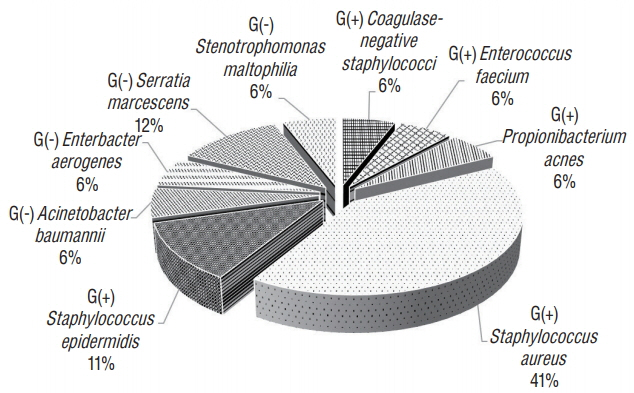

Of the 1576 cases included, 30 showed infection, for an overall SSI rate of 1.9%. Organ/space infection was the most common, found in 21 out of the 30 cases (70%). Staphylococcus aureus was the most common (41%) of all bacteria, and Serratia marcescens (12%) was the most common among gram-negative bacteria. In univariate analyses, the p-values for age, preoperative hospital stay duration, and over T-hour were <0.2. In a multivariate analysis of these variables, only preoperative hospital stay was significantly associated with the incidence of SSI (p < 0.001), whereas age and over T-hour showed a tendency to increase the risk of SSI (p=0.09 and 0.06).

CONCLUSION

Surveillance systems play important roles in the accurate analysis of SSI. The incidence of SSI after neurosurgical procedures assessed by a national surveillance system was 1.9%. Future studies will provide clinically useful results for SSI when data are accumulated.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). ASA physical status classification system. Available at : https://www.asahq.org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-status-classification-system.2. Blomstedt GC. Infections in neurosurgery: a retrospective study of 1143 patients and 1517 operations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 78:81–90. 1985.

Article3. Buang SS, Haspani MS. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after a neurosurgical procedure: a prospective observational study at Hospital Kuala Lumpur. Med J Malaysia. 67:393–398. 2012.4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surgical site infection (SSI) event. Available at : http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf.5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections. Available at : https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/17pscnosinfdef_current.pdf.6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health then and now: celebrating 50 years of MMWR at CDC. Available at : https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6004.pdf.7. Chiang HY, Kamath AS, Pottinger JM, Greenlee JD, Howard III MA, Cavanaugh JE, et al. Risk factors and outcomes associated with surgical site infections after craniotomy or craniectomy. J Neurosurg. 120:509–521. 2014.

Article8. Dixon RE, Centers for Disease Control, Prevention (CDC). Control of health-care-associated infections, 1961-2011. MMWR Suppl. 60:58–63. 2011.9. Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 6:428–442. 1993.

Article10. Gastmeier P, Kampf G, Wischnewski N, Hauer T, Schulgen G, Schumacher M, et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in representative German hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 38:37–49. 1998.

Article11. Gaynes RP, Culver DH, Horan TC, Edwards JR, Richards C, Tolson JS, et al. Surgical site infection (SSI) rates in the United States, 1992-1998: the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System basic SSI risk index. Clin Infect Dis. 33(Suppl 2):S69–S77. 2001.

Article12. Hadid H, Usman M, Thapa S. Severe osteomyelitis and septic arthritis due to serratia marcescens in an Immunocompetent Patient. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2015:347652. 2015.13. Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Morgan WM, Emori TG, Munn VP, et al. The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol. 121:182–205. 1985.

Article14. Hall WA, Truwit CL. The surgical management of infections involving the cerebrum. Neurosurgery. 62(Suppl 2):SHC519–SHC530. discussion 530-531, 2008.

Article15. Korinek AM. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after craniotomy: a prospective multicenter study of 2944 patients. The French Study Group of Neurosurgical Infections, the SEHP, and the C-CLIN Paris-Nord. Service Epidémiologie Hygiène et Prévention. Neurosurgery. 41:1073–1079. discussion 1079-1081. 1997.16. Korinek A, Golmard J, Elcheick A, Bismuth R, Van Effenterre R, Coriat P, et al. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after craniotomy: a critical reappraisal of antibiotic prophylaxis on 4578 patients. Br J Neurosurg. 19:155–162. 2005.

Article17. Kourbeti IS, Jacobs AV, Koslow M, Karabetsos D, Holzman RS. Risk factors associated with postcraniotomy meningitis. Neurosurgery. 60:317–325. discussion 325-326. 2007.

Article18. Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. The Lancet. 364:369–379. 2004.

Article19. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR, The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Am J Infect Control. 27:97–132. quiz 133-134; discussion 96. 1999.

Article20. McClelland III S, Hall WA. Postoperative central nervous system infection: incidence and associated factors in 2111 neurosurgical procedures. Clin Infect Dis. 45:55–59. 2007.

Article21. McLaws ML, Gold J, King K, Irwig LM, Berry G. The prevalence of nosocomial and community-acquired infections in Australian hospitals. Med J Aust. 149:582–590. 1988.

Article22. Narotam PK, van Dellen JR, du Trevou MD, Gouws E. Operative sepsis in neurosurgery: a method of classifying surgical cases. Neurosurgery. 34:409–415. discussion 415-416. 1994.23. Patir R, Mahapatra AK, Banerji AK. Risk factors in postoperative neurosurgical infection. A prospective study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 119:80–84. 1992.24. Plowman R. The socioeconomic burden of hospital acquired infection. Euro Surveill. 5:49–50. 2000.

Article25. Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, Carson J, Formanek M, Hafner J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 346:f2743. 2013.

Article26. Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 28:603–661. 2015.

Article27. von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. N Engl J Med. 344:11–16. 2001.

Article28. Wilhelmi I, de Quirós JB, Romero-Vivas J, Duarte J, Rojo E, Bouza E. Epidemic outbreak of Serratia marcescens infection in a cardiac surgery unit. J Clin Microbiol. 25:1298–1300. 1987.

Article29. Yu VL. Serratia marcescens: historical perspective and clinical review. N Engl J Med. 300:887–893. 1979.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Perspective of Nationwide Surveillance System for Surgical Site Infections

- Prospective Multicenter Surveillance Study of Surgical Site Infection after Spinal Surgery in Korea : A Preliminary Study

- Surgical Site Infection

- Surgical Site Infection Rates according to Patient Risk Index after Cardiovascular Surgery

- Current Status and Recent Changes in Nationwide Surveillance System for Surgical Site Infections